Original title: How bad policy favors memes over matter

Original article by: Chris Dixon

Release date: 04.20.2024

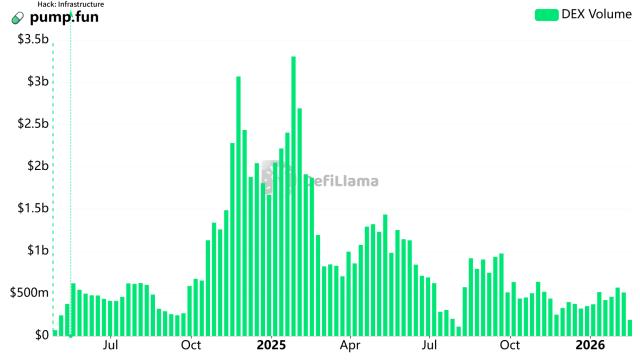

With cryptocurrency prices hitting new all-time highs recently, there is a risk of over-speculation in the cryptocurrency market, especially with the recent hype around meme coins. Why does the market keep repeating these cycles instead of supporting truly transformative blockchain-based innovations?

Meme coins are basically meme coins created by people in online communities who understand the meme. You may have heard of Dogecoin, which is based on the long-standing dog meme featuring Shiba Inu images in the internet community. When someone self-deprecatingly gave it a cryptocurrency that later had some economic value, it formed a wider online community. This "meme coin" reflects the diversity of internet culture, most of which are harmless, while many more meme coins are not.

But my goal in writing this article is not to defend or disparage meme coins. My goal is to point out the backwardness of a policy system that allows meme coins to thrive while blocking more productive blockchain businesses and tokens. Any meme maker can easily create, publish, and even have their tokens actively listed by exchanges, including those that disparage specific politicians and celebrities. But what about entrepreneurs who are trying to build real and lasting businesses? They are stuck in regulatory purgatory.

In fact, it is safer to launch a meme coin with no use right now than to launch a token with utility value. Think about this: if our securities market only incentivized GameStop meme stocks, but rejected companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Nvidia (whose products are obviously used by people every day), we would consider it a policy failure. However, current regulations encourage platforms to list meme coins instead of tokens with more utility value. The lack of regulatory clarity in the crypto industry means that platforms and entrepreneurs have been worried that the more productive blockchain tokens they are listing or developing may suddenly be deemed securities.

I call the distinction between these more speculative and productive use cases in the Crypto industry “computers vs. casinos.” The “casino” culture sees blockchain as a way to issue tokens primarily for trading and gambling. The “computer” culture is more interested in the blockchain itself, seeing it as a new platform for innovation, just like the web, social, and mobile networks before it. It’s possible that the Meme Coin community will evolve its token over time by adding more utility, after all, many of the disruptive innovations we use today once looked like a toy, too. “Utility” is important because at its core, the token is a new digital primitive that provides online property rights to anyone. Blockchain-based, more productive tokens make it possible for individuals and communities to own internet platforms and services, not just use them.

Such open-source, community-run services could solve many of the problems we face at big tech today: They could provide more efficient payment systems; they could verify proofs of authenticity to prevent deepfakes; they could allow for a more diverse range of people to join, or leave, specific social networks (especially if you don’t like their censorship policies, or if those networks selectively drive users away and keep users). They could give users a vote in a platform’s decisions, especially if those users’ livelihoods depend on that platform. They could tokenize “proof of humanness” to combat AI. Or they could generally serve as a decentralized counterweight to corporate centralization.

Our legal framework should encourage this kind of innovation. So why do we prioritize memes over substance? U.S. securities law does not empower the SEC to make merit-based judgments about investments, nor is it the SEC’s job to end speculation entirely. Rather, the agency’s role is to 1) protect investors; 2) maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets; and 3) facilitate capital formation. When it comes to digital asset markets and tokens, the SEC has failed on all three of these goals.

The main test the SEC uses to determine whether something is a security is the 1946 Howey test, which involves evaluating a number of factors, including whether there is a reasonable expectation of profit due to the managerial efforts of others. Take Bitcoin and Ethereum, for example: while both crypto projects began as one person’s vision, they have evolved into communities of developers that are not controlled by a single entity, so potential investors don’t have to rely on anyone’s “managerial efforts.” These technologies now operate like public infrastructure rather than as proprietary platforms.

Unfortunately, other entrepreneurs who are building innovative projects have no idea how to get the same regulatory treatment as Bitcoin and Ethereum. Bitcoin, founded in 2009, and Ethereum, founded in 2013-2014, are the only significant blockchain projects to date, both of which were established more than a decade ago, that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has explicitly or implicitly deemed to have no regulatory efforts involved. The SEC’s lack of candor and approach, including through enforcement regulation, to applying the Howey test has also led to much confusion and uncertainty in the industry. While there are good reasons for the Howey test, it is inherently subjective. The SEC has broadly expanded the meaning of the test to the point that ordinary assets, even things like Nike shoes, can be considered securities today.

Meanwhile, the Meme Coin project has no developers, creating the illusion that no Meme Coin investors are dependent on anyone’s “management efforts.” As a result, Meme Coins are able to spread, while innovative projects struggle. This creates a situation where investors ultimately face greater risk, not less.

The answer is not less regulation, but better regulation. Specific solutions include introducing carefully tailored disclosures to provide more information to ordinary investors. Another solution is to require long lock-up periods to prevent the hidden market harms caused by overnight wealth and incentivize more long-term construction.

Regulators implemented similar protections following the Great Depression, which followed the boom of the 1920s and the stock market crash of 1929. When these guidelines were in place, we saw unprecedented growth and innovation in our markets and economies. It’s time for regulators to learn from past mistakes and pave the way for a better future for all.

The author is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where he leads the crypto fund and is the author of “Read Write Own.”

A condensed version of this article originally appeared in the Financial Times on April 18, 2024 and was published on April 19, 2024.