Author: Fallen Flower, Antonio

Recently, Brian Armstrong, billionaire and CEO of cryptocurrency exchange Coinbase, stated that he is preparing to invest in a US startup focused on human embryo gene editing.

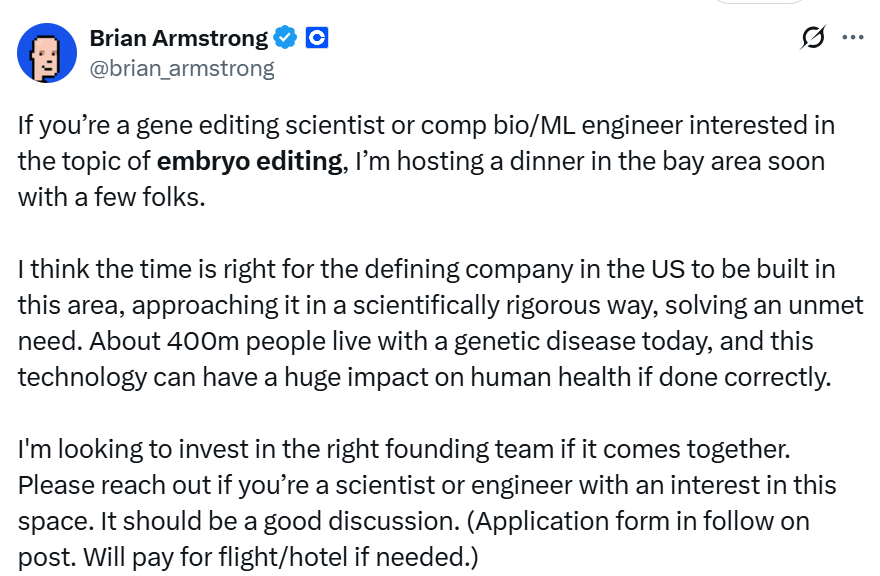

He publicly recruited gene editing scientists or computer biology/machine learning engineers on social media X, intending to form a founding team to conduct "embryo editing" research targeting unmet medical needs, such as genetic diseases. He invited them to apply for a private dinner, requiring applicants to fill out a form and answer questions, including "What awesome thing have you created?"

He attached a Pew Research Center public opinion poll from 7 years ago to his post. The poll showed that Americans strongly support changing babies' genes if it can cure diseases, although the same poll also found that most people oppose experiments on embryos.

Just a few weeks ago, multiple biotechnology industry organizations and academic groups jointly called for a 10-year ban on heritable human genome editing, pointing out that the technology not only has limited practical medical uses but also brings long-term risks with unknown consequences.

These institutions warned that the ability to "program" ideal traits or remove unfavorable genes could lead to the birth of a new "eugenics" that would "fundamentally alter the trajectory of human evolution".

So far, no US company has publicly conducted embryo editing research, and the federal government does not fund embryo research at all. In the United States, embryo gene editing research is only conducted by two academic centers: the center of gene editing scientist Dieter Egli at Columbia University and a center at Oregon Health & Science University.

Research funding for such studies is relatively limited, mainly relying on private grants and university funds. Many researchers at these centers say they welcome the idea of well-funded companies advancing this technology. "We sincerely welcome such cooperation," said Paula Amato, a reproductive doctor at Oregon Health & Science University and former president of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

They believe that if a billionaire lobbies for this, the ban on gene-edited babies might change.

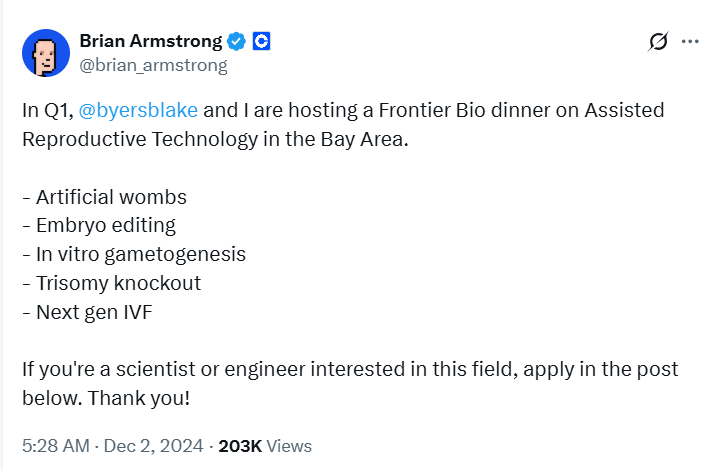

In December 2024, Armstrong announced on X that he and investor Blake Byers were preparing to meet with entrepreneurs working on "artificial wombs", "embryo editing", and "next-generation in vitro fertilization". They previously co-founded NewLimit, a company aiming to extend human health lifespan through epigenetic reprogramming, which has received nearly $300 million in funding. Byers had stated that a significant portion of global GDP should be used for "immortality" research, including biotechnological methods and ways to upload human consciousness to computers.

Now, the "embryo editing" entrepreneur meetup is on the agenda, scheduled for the third quarter of 2025 in the San Francisco Bay Area. Guests include postdoctoral researcher Stepan Jerabek from the Egli lab, who has been testing base editing techniques in embryos; another guest, Lucas Harrington, is a gene editing scientist who studied under Nobel Chemistry Prize winner Jennifer Doudna.

Harrington stated that the venture capital group SciFounders, which he helps operate, is also considering founding an embryo editing company. In an email, he said: "We hope a company can empirically assess whether embryo editing is safe and are actively exploring incubating a company to undertake this work. We believe professional scientists and clinicians are needed to safely evaluate this technology."

Additionally, he criticized the bans and moratoriums on the technology. He argued that these bans and suspensions cannot prevent the application of gene editing technology but may push it into the shadows, reducing its usage safety. He revealed that some biohacker organizations have quietly raised small amounts of funding to advance the technology.

In contrast, Armstrong's public statement on X platform demonstrates a more transparent attitude. "This time it looks serious, they really want to push the project forward," Egli said. The scholar hopes that the Coinbase CEO could fund part of his laboratory's research, "I think his public statement is valuable - it can gauge public opinion, observe various reactions, and promote public discussion".

In 2015, news first emerged from China about researchers performing CRISPR gene editing on human embryos in the laboratory, causing global shock - people realized how theoretically simple it was to change human genetic characteristics. In 2017, a research report from Oregon claimed they successfully corrected pathogenic DNA mutations in laboratory embryos cultivated from patient egg and sperm cells.

However, this breakthrough was fraught with complexity. Egli and other scholars discovered through more rigorous testing that CRISPR technology might actually cause severe cellular damage, often leading to large chromosome segment deletions. Besides the chimeric phenomenon (different editing in different cells), this seemingly precise DNA editing technique actually causes hard-to-detect destructive consequences.

While the public debates the ethics of "CRISPR babies", the scientific community focuses on fundamental scientific challenges and solutions. Subsequently, the industry turned to base editing technology, which changes a single DNA base. This method causes fewer unexpected effects and theoretically can provide embryos with multiple beneficial gene variations, rather than a single modification. The early methods actually cut the double helix structure, causing damage and leading to entire gene disappearance.

Currently, gene editing technology is only approved for treating adult diseases, such as gene therapy for sickle cell anemia, which costs over $2 million. In comparison, embryo editing costs could be extremely low: if editing occurs early in embryo formation, all somatic cells will carry the modified gene.

However, gene editing technology has not yet reached the mature stage of creating "custom babies". To achieve this goal, many technical challenges still need to be overcome, including precisely designing editing systems and establishing systematic methods to detect abnormal DNA changes in embryos. This is the direction that Armstrong's proposed investment company needs to tackle.

As of publication, Armstrong has not responded to an email from MIT Technology Review seeking comment on his plans, and his company Coinbase has not replied either.