Author: Byron Gilliam, Blockworks

Original Title: Fiscal dominance: Behind the Fed's growing and unavoidable burden

Translated and Compiled by: BitpushNews

Once upon a time, Federal Reserve chairmen could freely "lecture" politicians about their irresponsible spending habits, and it was a delightful era.

For example, in 1990, Alan Greenspan told Congress he would lower interest rates, but only if Congress reduced the deficit.

In 1985, Paul Volcker even provided specific numbers, telling Congress that the Fed's "stable" monetary policy depended on Congress cutting about $50 billion from the federal budget deficit. (Ah, those were the days of a $50 billion federal debt, not just a rounding error.)

In both cases, the Fed chairmen were subtly threatening Congress and the White House with recession risks: you have a nice economy now, it would be a shame if something were to happen.

However, now the situation is reversed, with U.S. President Trump "lecturing" the Federal Reserve about interest rates.

In recent weeks, Trump has stated that the federal funds rate is "at least 3 percentage points too high", insisting there is "no inflation", and mocking Fed Chairman Jerome Powell as "Too Late Powell".

This is also a form of pressure: you have nice central bank independence...

Trump also lobbied for lower rates during his first term. Like almost all modern U.S. presidents, he wanted the Fed to stimulate the economy.

However, this time, it goes beyond that: Trump wants the Fed to finance the deficit.

Trump's confrontation with Powell appears to be about current interest rate levels (the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) kept rates unchanged today, which will likely displease the president).

But what the president has been threatening is "fiscal dominance" - a state where monetary policy is subordinate to government spending needs.

"Our rates should be 3 points lower, saving the country $1 trillion per year," the president recently wrote on Truth Social in his characteristic casual capitalization style.

By repeatedly making such statements, Mr. Trump has made history as the first U.S. president to explicitly call for fiscal dominance.

But he is certainly not the first to acknowledge this possibility.

When Volcker and Greenspan threatened Congress with rate hikes, it brought to the surface the usually hidden connection between monetary and fiscal policies.

It worked for them: both Fed chairmen successfully used the threat of economic recession to prompt Congress to address deficit spending, a hopeful precedent.

But this strategy seems unlikely to work this time.

Chairman Powell frequently warns about the risks of growing deficits, even explaining that higher deficits could mean higher long-term interest rates.

But it's hard to imagine him making such clear threats as Volcker and Greenspan did - perhaps because he knows he is in an obviously weak bargaining position.

In the 1980s, the most worrying effect of rate hikes was recession, and the Fed was willing to risk this to compel Congress to change its spending habits.

At that time, legislators faced an ever-expanding defense budget and a stagnant economy, both of which seemed manageable.

Federal debt as a percentage of GDP was only 35% and seemed easy to manage.

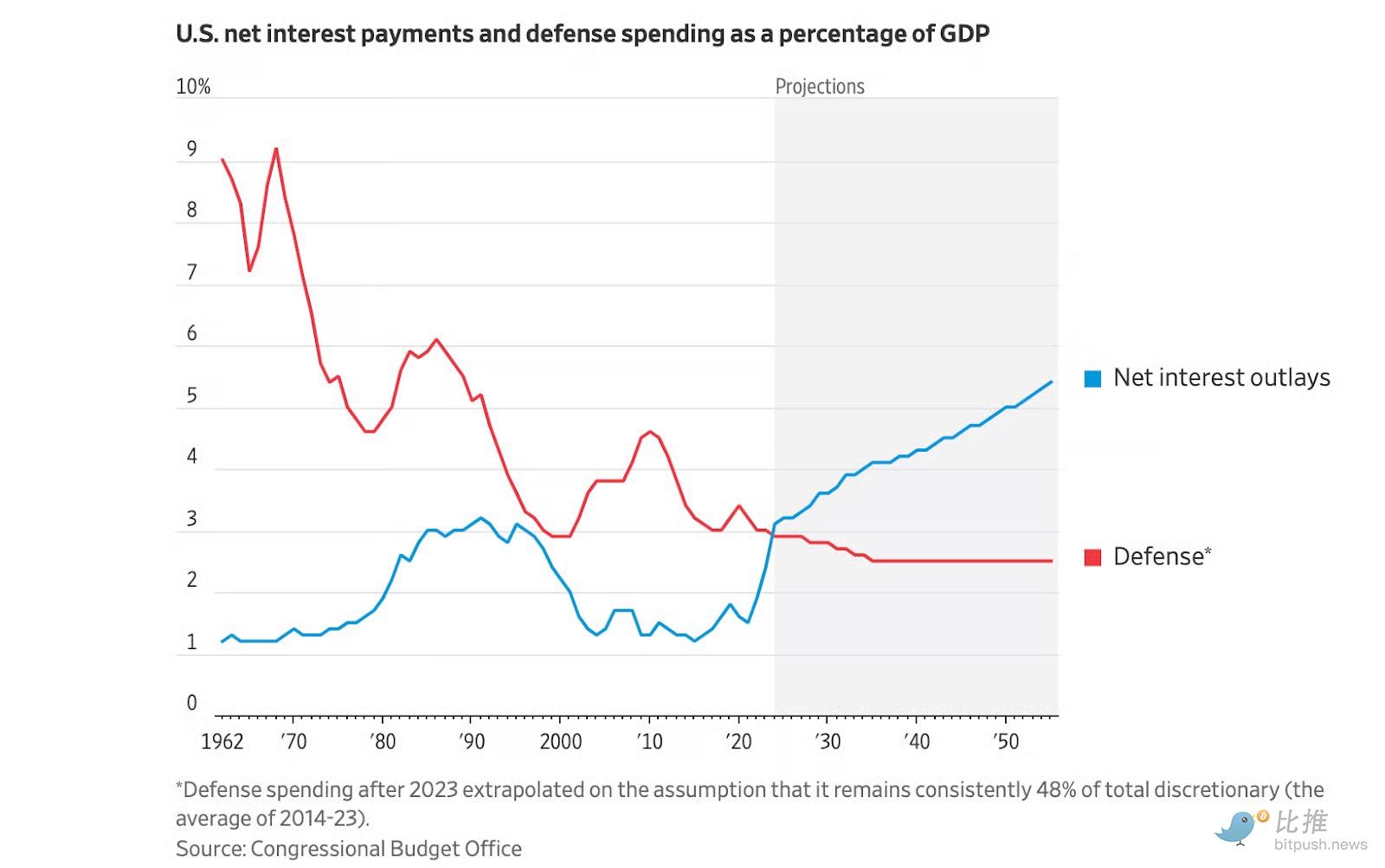

Now, federal debt is 120% of GDP, and U.S. interest payments even exceed defense spending:

<Chart: The rapidly rising blue line represents federal debt interest payments as a percentage of GDP, far exceeding defense spending>

The rapidly rising blue line in the chart is now possibly the biggest budget issue.

This puts the Fed in a dilemma: it wants to use rate hikes as a tool to "cure" the government's fiscal problems, but the government's debt is now so large that rate hikes might become a "poison" that makes fiscal problems worse.

Of course, the Fed can take the risk.

But if rate hikes lead to further deficit increases, who will blink first: the Fed or the White House?

Before answering, consider that now 73% of federal spending is non-discretionary, compared to only 45% in the 1980s.

Believing the Fed can win a confrontation about deficits would mean believing Congress is willing to make significant cuts to non-discretionary spending like Social Security and Medicare.

This seems, well, incredible.

Especially now, with a president who seems completely unmoved by the country's growing debt situation.

This might stem from his experience in the 1990s as a heavily indebted real estate developer.

"I figured this was the bank's problem, not mine," Trump later wrote about being unable to repay debt, "What the hell do I care? I even told a bank, 'I told you, you shouldn't have lent me money, I told you that damn deal was no good.'"

Now, as president, when Trump tells Powell rates should be lower, what he really means is that national debt is the Fed's problem, not his.

He's not wrong.

"When debt interest payments rise and fiscal surpluses are politically unfeasible," wrote former U.S. Treasury economist David Beckworth, "something must give. That something is more debt, more money creation, or both."

Yes, the Fed could try Volcker/Greenspan's old trick of threatening Congress with higher rates.

But Powell probably knows that doing so would only exacerbate a problem that the Fed might ultimately need to solve - and accelerate the timeline for its forced resolution.

"If debt levels are too high and continue growing," Beckworth explained, "the Fed's responsibility becomes accommodating - by lowering rates or monetizing debt."

He warns that this is the Fed's true existential threat, not Trump: "When a central bank is forced to accommodate fiscal needs, it loses economic independence."

Beckworth remains hopeful that it might not come to that.

Perhaps it really won't. We've seen how unpopular inflation is, so another round of inflation might force legislators to address the deficit.

But what makes him desperate is that focusing on Trump's demand for lower rates is a distraction: "What we're witnessing is less about Trump himself and more about the growing and unavoidable fiscal demands being placed on the Fed."

Trump is the first to explicitly make these demands, probably because he knows the current fiscal policy of the U.S. government is unsustainable.

But everyone knows this, even the government itself.

Now the only question is: who will deal with it?