Author: Murch

Source: https://x.com/murchandamus/status/1854678133896626293

Each full node stores unconfirmed transactions in its own "mempool." This cache (mempool) is a crucial resource for the node, enabling a peer-to-peer transaction forwarding network. By knowing and verifying the vast majority of transactions (which will be included) before a new block is announced, block propagation is also faster.

By observing which transactions first appear in the transaction pool and then receive block confirmation, a node can unilaterally estimate the necessary transaction fee rate for a transaction that failed to bid for a block space and was subsequently confirmed.

Nodes forward transactions to all their peers, which is crucial for user privacy and network censorship resistance. Fast and unrestricted access to unconfirmed transactions allows anyone to construct competitive block templates and become a miner without permission.

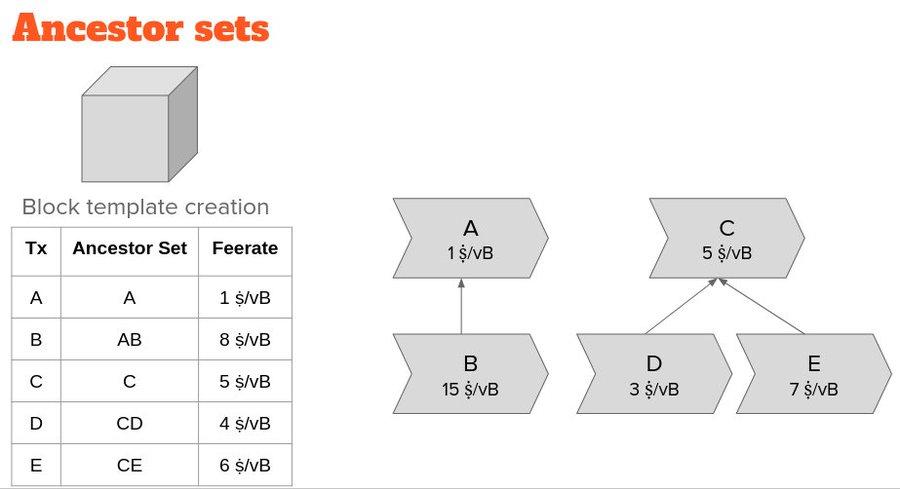

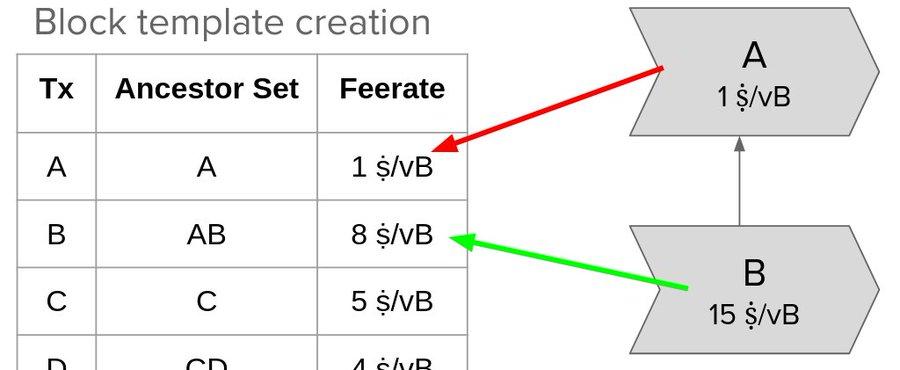

Currently, Bitcoin Core tracks each transaction from the perspective of "ancestors." It first selects the transaction with the highest ancestor set fee rate to enter the block, then updates the ancestor set and fee rate of all affected descendant transactions, and repeats this process continuously, greedily assembling a block template.

This method has a drawback: we need to continuously update transaction data while constructing block templates, and we can only predict the mining score (the fee rate for selecting a transaction into a block) after considering all relevant factors.

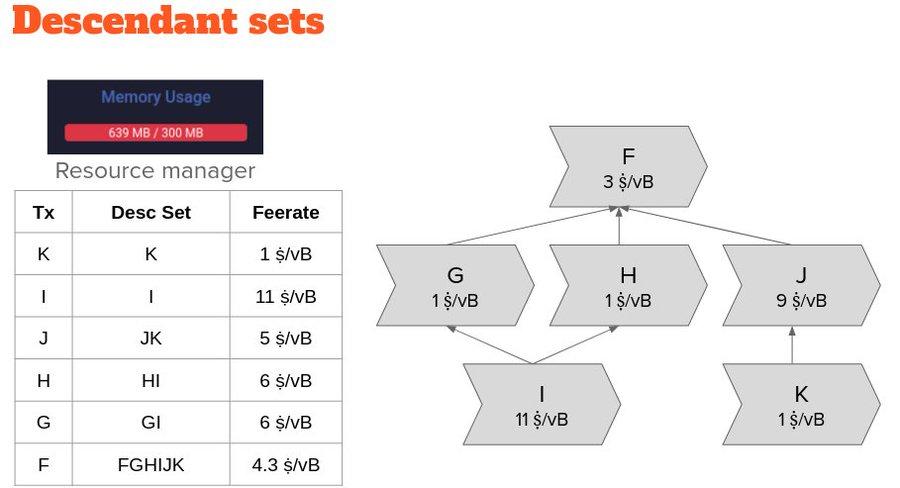

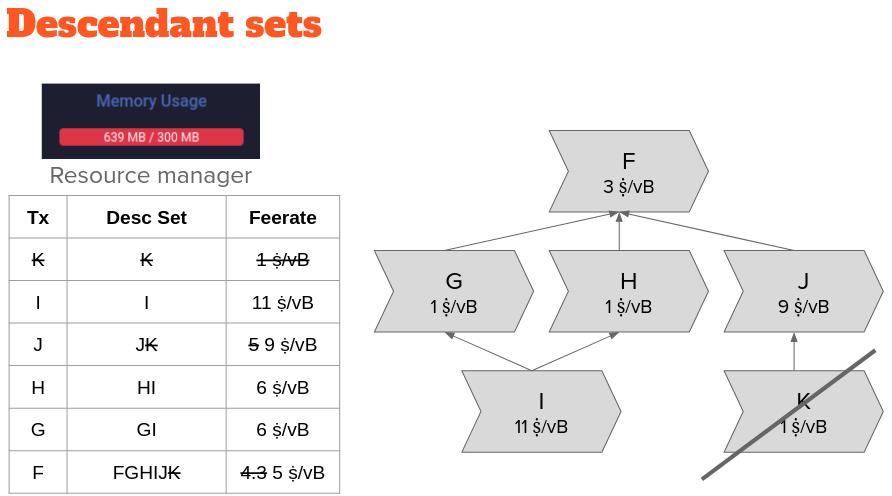

Sometimes, the demand for block space becomes so urgent that our nodes receive more transactions than they can cache. Once the transaction pool overflows, we need to evict the transactions that are least attractive for mining.

Unfortunately, because a transaction may depend on other transactions, we can only accurately predict which transaction is the least attractive after calculating all the transactions ahead of it. It's unacceptable to expend such a large amount of computation every time a transaction is expelled.

Therefore, we employ a heuristic approach to imperfectly evaluate which transaction should be evicted first. Furthermore, we track each transaction from the perspective of a "descendant set," using the lowest descendant set score as an indicator for evicting a transaction.

If the rate of a single transaction or the set of descendants of a leaf transaction in our transaction pool is the lowest, then this result is accurate—and it can be evicted. However, this heuristic may not correctly identify the transaction that was last selected for the block template.

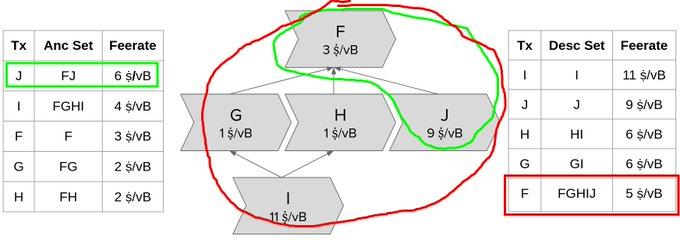

In the transaction diagram example above, "transaction J" has the highest ancestor set fee rate and will be expelled along with its ancestor "transaction F"; however, F itself has the lowest descendant set fee rate, so it will be expelled along with all its descendant transactions (including J).

Finally, as is well known, the RBF (Transaction Fee Replacement) rule used by Bitcoin Core , inspired by BIP-125, does not always produce incentive-compatible replacement transactions. We know for certain that in some cases, accepting a replacement transaction does not improve the transaction pool situation; and in other cases, a replacement transaction that could improve the transaction pool situation is rejected.

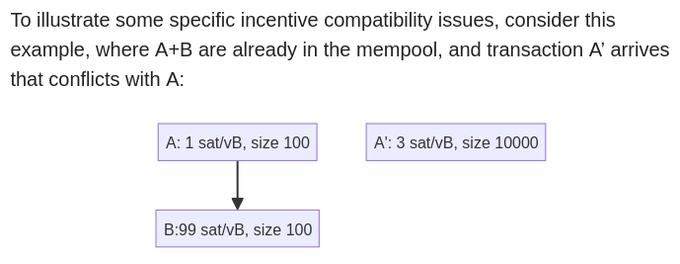

- To illustrate some specific incentive compatibility issues, consider this example: "Transaction A" and "Transaction B" are already in the middle of a trade, and then "Transaction A'" (which conflicts with Transaction A) arrives.

This brings us to the "Cluster Mempool" proposal (thanks to Suhas Daftuar and Pieter Wuille): How wonderful it would be if we could always know the order of the entire mempool and always know the mining score of each transaction.

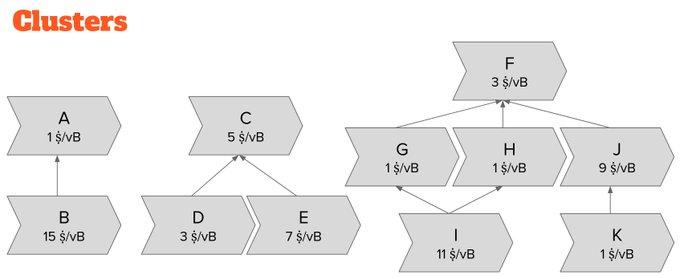

Instead of using the perspective of "ancestor set" and "descendant set" to track transactions, we track the "family" of transactions—the entire "family" of related transactions.

Each transaction belongs to only one group. Starting with any transaction belonging to a group, by adding all its child transactions and parent transactions (and the child transactions of these child transactions, the parent transactions of these parent transactions, and so on), the group can be completely identified.

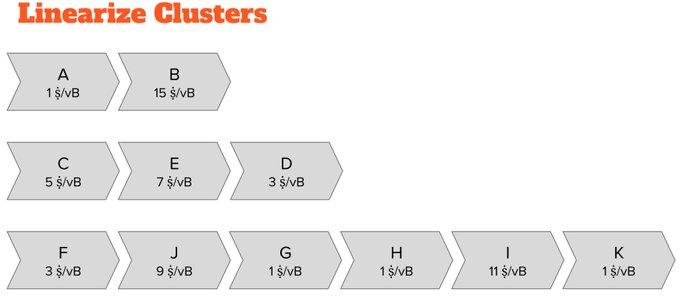

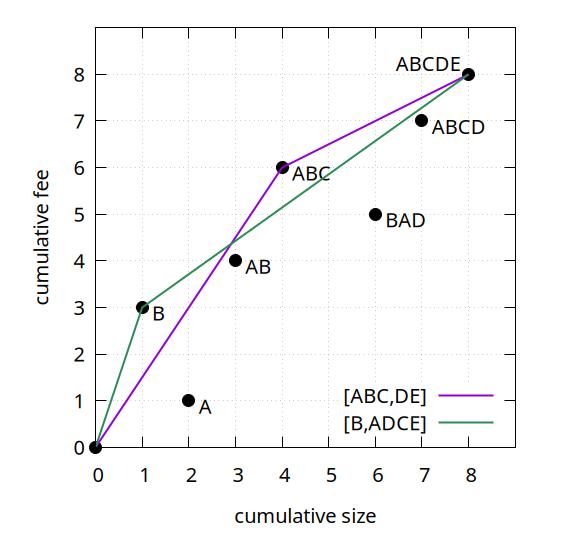

Then, we can “linearize” each group: we can transform the transaction graph into a list and sort them according to their priority in terms of the likelihood of them being selected into the block template.

So far, we can view population linearization as running a block construction algorithm once within a population and recording the order in which these transactions enter the block.

Linearization can be computationally intensive in a large, structurally complex population.

The computational cost of operating on clusters limits their scalability. We can set this issue aside for now, but if you'd like to learn more, Pieter Wuille wrote a paper on the Delving Bitcoin forum discussing how to efficiently linearize clusters: Introduction to cluster linearization.

Previously, we used ancestor sets to discover (for example) situations in CPFP where it becomes attractive to package both parent and child transactions simultaneously.

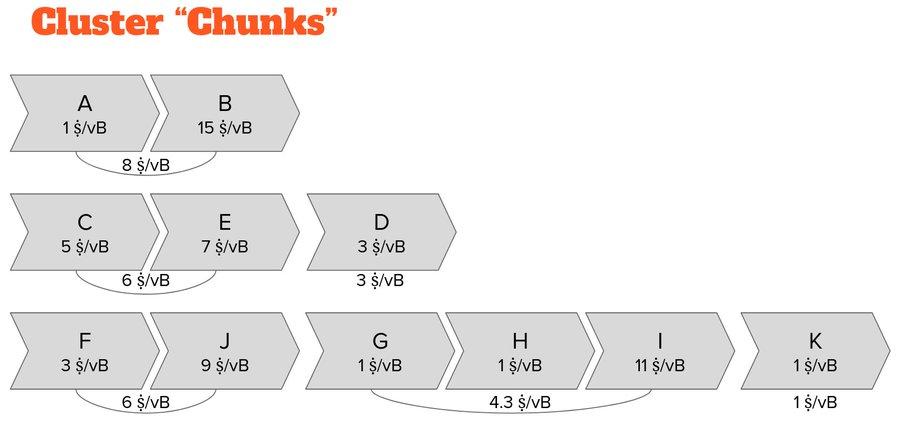

Linearization of transaction groups allows us to easily identify transaction fragments that will naturally be packaged together in a block. When a high-fee transaction follows a low-fee transaction, we can classify them as "separate groups".

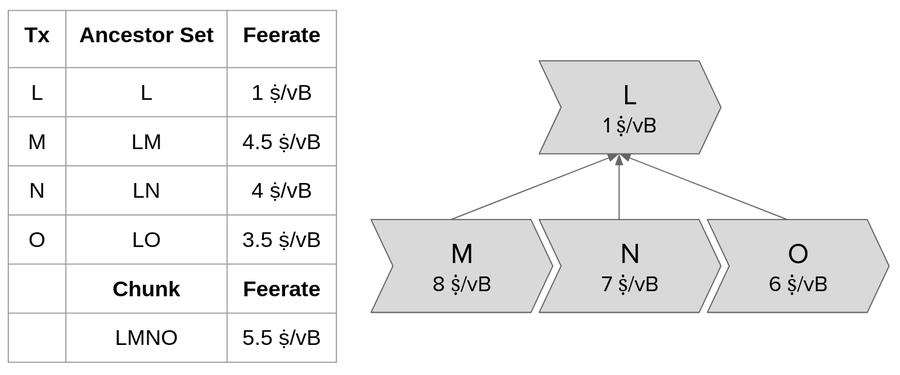

These branches have a huge advantage over the ancestor set: (1) Compared with the parent transaction, multiple sub-transactions with higher rates can naturally form a branch, and the rate of this branch will be higher than the rate of any sub-transaction's ancestor set!

(2) A branch's fee rate depends only on the transactions within the branch. Even when an ancestor is selected into a block, a branch's fee rate will remain unchanged—we can pre-calculate the branch's fee rate and read it as the mining score for all transactions within the branch!

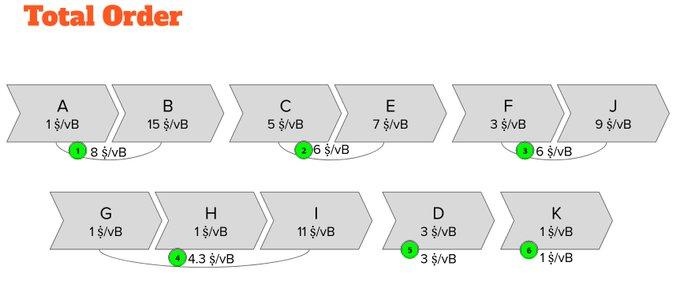

Therefore, block construction directly becomes a process of repeatedly selecting the sub-group with the highest fee rate from all subgroups until the block template is full. This also gives us an implicit global ordering of the entire transaction pool.

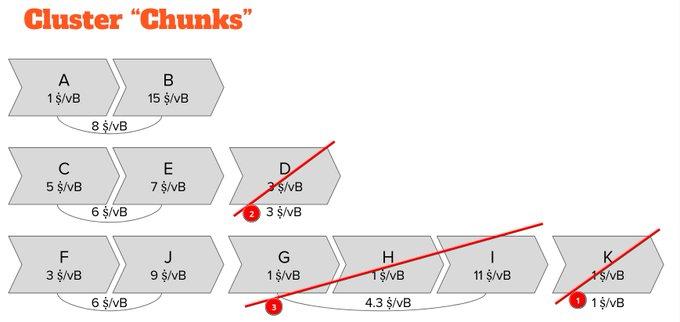

This also means that we know exactly which branch will be dug up last. Expulsion simply becomes removing the branch with the lowest fee across all clans.

The conclusion is that the "ethnic trading pool" gives us:

- Faster block building speed

- Mining points are always available

- The near-optimal small-scale expulsion

- A better framework (the so-called "rate chart") to think about RBF trading packages

The cost is merely some pre-calculated expenses and constraints on the size of the population.

(over)