Author: Kalle Rosenbaum & Linnéa Rosenbaum

This chapter analyzes what "decentralization" is and why it's so crucial to Bitcoin's functionality. We distinguish between "miner decentralization" and "full node decentralization," and discuss what they bring to "censorship resistance" (one of Bitcoin's core attributes). The discussion then shifts to understanding that "neutrality"—or "permissionless access" for users, miners, and developers—is a necessary attribute of any decentralized system. Finally, we also mention the difficulty of understanding decentralized systems like Bitcoin and offer some mental models to help you grasp its concepts.

A system without any central point of control is called " decentralized ." Bitcoin was designed to avoid having a central point of control, or more accurately, a central point of censorship . Decentralization is a tool for achieving censorship resistance .

Bitcoin's decentralization has two main aspects: miner decentralization and full node decentralization. "Miner decentralization" refers to the fact that transaction processing is neither executed nor coordinated by any central entity. "Full node decentralization" refers to the fact that block verification (the data output by miners) is completed at the edge of the network, ultimately by network users, rather than by a few trusted authorities.

1.1 Decentralization of Miners

Before Bitcoin, there were attempts to create electronic currencies, but most of them failed due to a lack of decentralized governance and censorship resistance.

In Bitcoin, decentralized mining means that the ordering of transactions is not accomplished by any single entity or fixed group, but rather by a collective of all actors wishing to participate in the ordering; this mining collective is a dynamic set of users. Anyone can join or leave at their own discretion. This property makes Bitcoin censorship resistant.

If Bitcoin is centralized, it becomes vulnerable to scrutiny by those who want to censor it, such as governments. It will suffer the same fate as previous attempts to create electronic currencies. In the introduction to a paper titled "Unlocking Blockchain Innovation with Anchored Sidechains," the author explains why earlier electronic currencies failed to survive in hostile environments (see also Chapter 6 of this book):

In 1983, David Chaum proposed digital cash as a research topic, which was based on the premise of trusting a central server to prevent "double-spending" [Cha83]. To mitigate the privacy risks of individuals relying on this trusted central participant, and also to enforce fungibility, Chaum introduced blind signatures, which provided a cryptographic tool to prevent the signatures of this centralized service provider (which themselves represent money) from being linked, while still allowing the centralized service provider to prevent double-spending. This reliance on a centralized server became the Achilles' heel of digital cash [Gri99]. Although this single point of failure could be decentralized by replacing the signature of a single central service provider with threshold signatures from multiple signers, the ability to identify and ensure that the signers are not the same person remains important for auditability. This still makes the entire system vulnerable to failure, because each signer could malfunction, or be deliberately made to malfunction, one after another.

— Multiple authors, "Using Anchored Sidechains to Enable Blockchain Innovation" (2014)

Clearly, using a centralized server to sort transactions is not a viable option due to the high risk of censorship. Even replacing the centralized service provider with a fixed consortium of N service providers, requiring at least M of them to approve a sort, still presents challenges. The problem essentially becomes: users must unanimously agree on this set of N service providers, and, in the event of a malicious service provider, how can users switch service providers without relying on a central authority?

Let's imagine what would happen if Bitcoin were censorable. Censors would force users to report their identity, where their money came from, and what they bought, otherwise their transactions wouldn't be recorded on the blockchain.

Similarly, the lack of censorship resistance allows censors to force users to accept new system rules. For example, they could impose a change that allows users to inflate the money supply, thereby enriching themselves. In such an event, users validating blocks have three options:

- Accept: Accept the change and adopt the new rule in their full nodes.

- Reject: Reject this change; this will leave them in a system that no longer processes transactions, because the censor's block will be considered invalid by this user's full node.

- Migration: Nominate a new central control point; all users must figure out how to collaborate and reach a consensus on this new central control point. Even if they succeed this time, the same problems may recur in the future because the entire system is still auditable.

None of the options would benefit the user.

The decentralization that enables censorship resistance is what distinguishes Bitcoin from other monetary systems, but the " double-spending problem " makes it difficult to achieve. The double-spending problem refers to ensuring that no one can spend the same coin twice; many have argued that this problem cannot be solved through decentralization. Satoshi Nakamoto discussed how to solve the double-spending problem in his Bitcoin white paper :

In this paper, we propose a solution to the problem of double-spending: using a peer-to-peer, decentralized timestamp server to generate computational evidence for the temporal order of transactions.

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System (2008)

Here, he used the particularly odd phrase "peer-to-peer, decentralized timestamp servers." The key word is actually " decentralized ," which in this context means there is no single point of control. Satoshi Nakamoto then explained why proof-of-work is the solution. To date, no one has offered a better explanation than Gregory Maxwell on Reddit ; on that occasion, someone proposed limiting miners' hashing power to prevent potential 51% attacks.

Decentralized systems like Bitcoin use public elections. But you can't have "people" have votes in a decentralized system because that would require a centralized participant to allow people to vote. Instead, Bitcoin uses computing power as votes because computing power can be verified without the help of any centralized third party.

—Gregory Maxwell, r/Bitcoin subreddit (2019)

This post also explains why the decentralized Bitcoin network is able to reach consensus on the ordering of transactions through proof-of-work. It then concludes that a 51% attack is not particularly concerning compared to those who neither care about nor understand Bitcoin's decentralized nature.

A much greater risk for Bitcoin is that the public does not understand, care about, or protect its decentralized nature; and decentralization is where Bitcoin's true value lies compared to its centralized alternatives.

—Gregory Maxwell, r/Bitcoin subreddit (2019)

This conclusion is important. If people don't protect Bitcoin's decentralization—its proxy for censorship resistance—Bitcoin could become a victim of centralized power until it becomes highly centralized and censorship becomes possible. At that point, most (or even all) of Bitcoin's value will cease to exist. This leads us to the next topic: the decentralization of full nodes.

1.2 Decentralized Full Nodes

In the above text, we mainly discussed the decentralization of miners, and how centralized miners would allow censorship. But there is another aspect to decentralization, called " full node decentralization ".

The importance of full node decentralization is related to "trustlessness" (see also Chapter 2 of this book). Suppose a user stops running their full node due to (for example) a sharp increase in operating costs. Afterward, they will have to use other methods to interact with the Bitcoin network, perhaps using a web wallet or a lightweight wallet, both of which require users to trust the service providers to some extent. Users will also shift from directly enforcing the network's rules to trusting others to do so. Now, suppose the vast majority of users delegate the enforcement of consensus rules to a trusted entity. At this point, the network could quickly become centralized, and the rules could be altered by malicious actors with ulterior motives.

In an article in Bitcoin Magazine , Aaron van Wirdum interviewed several Bitcoin developers, asking them for their views on decentralization and the risks of increasing the Bitcoin block size limit. Such discussions were prevalent between 2014 and 2017, with many advocating for increasing the block size limit to improve transaction throughput.

A strong argument against increasing block size is that it would increase the cost of verifying blocks (see also the chapter on scalability in this book). If verification costs increase, it would cause some users to stop running their full nodes. This, in turn, would prevent more people from using Bitcoin in a trustless manner. The article quotes Pieter Wuille to explain the risks of full node centralization:

If a large number of companies run their own full nodes, then implementing a different set of rules in the Bitcoin network would require convincing them all. In other words, the decentralized nature of block verification gives weight to the consensus rules. However, if the number of full nodes becomes very scarce, for example, because everyone uses the same web wallet, exchange, SPV wallet, or mobile wallet, regulation becomes possible. Moreover, if authoritative bodies can regulate the consensus rules, it also means they can change everything that makes Bitcoin Bitcoin, even the 21 million BTC supply limit.

— Pieter Wuille, A Decentralizer’s Perspective (2015)

That's it. Bitcoin users should run their own full nodes to prevent regulators and large companies from trying to change Bitcoin's consensus rules.

1.3 Neutrality

Bitcoin is neutral, or, in more common terms, permissionless. This means that Bitcoin doesn't care who you are or what you use it for.

Bitcoin is neutral, which is an advantage and the only way it can work. If it were controlled by a single organization, it would just be another virtual item, and I wouldn't have any interest in it.

— wumpus in FreeNode online chat (punctuation added), #bitcoin-core-dev 2012-04-04T17:34:04 UTC

As long as you follow its rules, you are free to use it to do whatever you want without asking anyone for permission. This includes mining , trading , and developing protocols and services on Bitcoin.

- If mining requires a license, we need a central authority to choose who can mine. This could very well force miners to sign legal contracts agreeing to have their transactions reviewed at the whim of this central authority, which defeats the purpose of mining in the first place.

- If people need to provide personal information, declare the purpose of their transactions , or, if not, prove the worth of their transactions when using Bitcoin, then we need a central authority to approve users and transactions. Again, this would lead to censorship and exclusion.

- If developers need permission to develop protocols on Bitcoin, then only protocols approved by the central developer council will be developed. Due to government intervention, this will inevitably exclude all privacy-protecting protocols and all attempts to improve decentralization.

At all levels, any attempt to restrict who can use Bitcoin and for what purpose will harm Bitcoin and make it no longer consistent with its value proposition.

Pieter Wuille answered a question on Stack Exchange about the relationship between blockchain and regular databases . He explained that permissionless access is achieved through the use of proof-of-work and economic incentives. His conclusion was:

Using a trustless consensus algorithm like Proof-of-Work (PoW) does offer something other algorithms can't (trustless participation, meaning no group of participants can vet your changes), but it also comes with a high cost, and its economic assumptions make it almost exclusively suitable for defining your own cryptocurrencies. This is probably one of the few places where it has actually been used.

—— Pieter Wuille, Stack Exchange (2019)

He explained that in order to achieve trustlessness, the system would likely need its own currency, thus "limiting its uses to almost exclusively cryptocurrency." This is because trustless participation, or mining, requires the system to have built-in economic incentives.

1.4 Understanding Decentralization

One striking aspect of Bitcoin is that it's difficult to understand why it's not controlled by anyone. There are no committees or executives in Bitcoin. Gregory Maxwell, in another forum post , amusingly compared it to the English language:

Many people struggle for a long time to understand autonomous systems, but they also have things like the English language in their lives—things they take for granted and never understand as a system. They are trapped in a mindset that assumes all the "things" they think about have an authority that controls them.

Bitcoin has no objective. Many who adopt it do so out of their own free will, and why they do so is entirely their own business. Those obsessed with the idea of authority might think it's all manipulated by some Bitcoin authority, but such an authority does not exist.

—Gregory Maxwell, r/Bitcoin subreddit (2022)

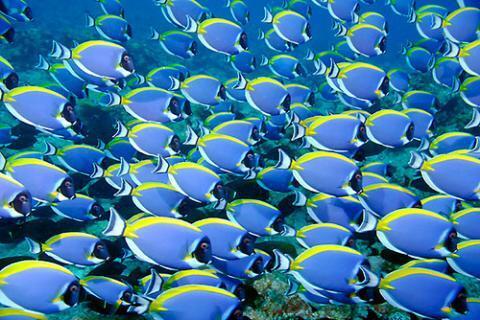

Bitcoin's ability to survive through decentralization is similar to the remarkable collective intelligence that has developed in many species in nature. Computer scientist Radhika Nagpal once spoke in a TED Talk about the collective behavior of schools of fish and how scientists use robots to mimic them.

Figure 1. The school of fish has no leader.

Secondly, and this is what I consider most remarkable: we know that schools of fish have no leader. Instead, this incredible collective thinking arises entirely from the interaction between one fish and another. To a certain extent, it is the interaction between these neighboring fish, or rather, their rules of arrangement, that make their collective activity possible.

—Radhika Nagpal, What Intelligent Machines Can Learn from Schools of Fish (2017)

She points out that many systems, whether natural or artificial, can operate in a leaderless mode, and they are powerful and resilient. Each individual interacts only with its neighboring individuals, and in this way, they come together to form something enormous.

Regardless of your understanding of Bitcoin, its decentralized nature makes it difficult to control. Bitcoin exists, and there's nothing you can do about it. It's something worth learning, not something to be dismissed.

1.5 Conclusion

We distinguish between full-node decentralization and miner decentralization. Miner decentralization is a tool for achieving censorship resistance, while full-node decentralization makes it difficult for the network's consensus rules to change without the broad support of users.

Bitcoin's decentralized nature allows for neutrality towards developers, users, and miners. Anyone can participate freely without requesting permission.

Decentralized systems may be difficult to understand, but there are mental models that can help, such as English or a school of fish.