Authors: Thomas Coratger, Srinath Setty

Introduction: The Post-Quantum Signature Transition

In Proof-of-Stake systems like Ethereum, digital signatures provide accountability for the hundreds of thousands of validators that secure the network. The sheer volume of attestations creates a significant scalability challenge: how to efficiently verify so many signatures? For this, Ethereum’s consensus layer adopted the BLS signature scheme, a choice that was pivotal in enabling the network to scale.

The advantage of BLS lies in its unique algebraic structure, which allows for highly efficient signature aggregation using cryptographic pairings (e: \mathbb{G}_1 \times \mathbb{G}_2 \to \mathbb{G}_Te:G1×G2→GT). The bilinearity of the pairing map allows for a remarkable property: the validity of an entire set of nn signatures can be confirmed with a single equation.

In Ethereum’s practical implementation, an aggregated signature is accompanied by a bitfield (the \texttt{aggregation_bits}aggregation_bits) that identifies which validators from a committee participated. A verifier uses this bitfield to compute the aggregate public key \sum pk_i∑pki before running the final cryptographic check. While the final check is constant-time (two pairings), the overall verification cost includes a linear-time step to construct this aggregate public key:

This model is essential for scalability and very well detailed in the Eth2 Book, but the security of BLS relies on problems that are not resistant to quantum computers. The necessary transition to a post-quantum alternative, such as the hash-based XMSS, reintroduces the scalability challenge. XMSS lacks the algebraic properties of BLS; its signatures are larger and computationally expensive to verify, making the individual verification of thousands of signatures per block infeasible.

The solution is a new form of signature aggregation using succinct arguments of knowledge (SNARKs) to generate a single, succinct proof for an entire set of signatures (while often referred to as constant-sized for simplicity, proofs from modern hash-based SNARKs are technically polylogarithmic in the size of the statement). Since validators are distributed across a peer-to-peer network, it is not practical for a single node to collect all signatures. Instead, aggregation must also occur in a decentralized fashion, where different nodes aggregate overlapping subsets of signatures. This “proof-of-proofs” requirement naturally leads to a recursive architecture. This article compares the two primary paradigms for implementing this recursion:

- Recursive SNARK Verification: Verifying a complete SNARK proof within another SNARK circuit.

- Specialized Recursive Primitives: Utilizing folding schemes to combine the underlying mathematical statements of proofs directly, avoiding a full verification step.

We analyze the mechanisms, performance, and trade-offs of each approach to inform the path for Ethereum’s post-quantum signature aggregation.

The Aggregation Framework

To handle attestations from a validator set that could scale to hundreds of thousands of participants, the post-quantum aggregation system must be designed as a multi-layered, parallelized process. Unlike the simple summation of BLS signatures, aggregating SNARK-based proofs requires a structured, recursive approach. This process unfolds across a peer-to-peer network of aggregator nodes, culminating in a single, succinct proof for on-chain verification.

BLS Aggregation in Practice: The Status Quo

Before detailing the post-quantum approach, it is useful to understand how aggregation is currently implemented with BLS signatures in Ethereum’s consensus layer. The core mechanism relies on tracking participation to ensure accountability, which is essential for applying rewards and penalties correctly.

Validators are organized into committees for each slot. When a validator in a committee creates an attestation, the signed object includes a field named \texttt{aggregation_bits}aggregation_bits. This is a bitlist where each position corresponds to a validator’s index within that specific committee. The attesting validator sets their own bit to 1.

Later, attestations from different validators that attest to the same view of the chain can be aggregated. This is done by performing a bitwise OR on the \texttt{aggregation_bits}aggregation_bits and adding the individual BLS signatures together (as an elliptic curve point addition). The result is a single \texttt{Attestation}Attestation object with a combined bitfield and one aggregate signature. To verify it, a node reconstructs the aggregate public key by summing the public keys of only those validators whose bits are set to 1 in the final \texttt{aggregation_bits}aggregation_bits. This system allows for the verification of hundreds of signatures with just a single, efficient pairing check, but it crucially retains a record of exactly who participated.

Tracking Participation with Bitfields in a Post-Quantum System

The post-quantum framework inherits this critical need for precise participation tracking. A proof that simply attests to the validity of an anonymous set of signatures would be insufficient for the consensus protocol. Therefore, the system continues to employ a bitfield to identify every signer.

In Ethereum’s permissionless model, the validator set is dynamic. To manage this, the beacon state maintains a canonical, ordered registry of all active validators at any given time. A validator’s index is its unique position within this global registry for a specific state. While the registry evolves as validators join or exit, the index provides a stable and unambiguous reference for any given consensus operation. This ensures that even in a dynamic environment, participation can be tracked with precision.

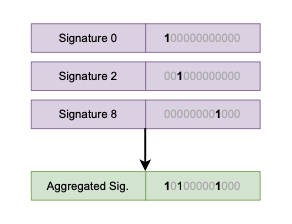

As illustrated in Figure 1, each post-quantum signature is associated with a bitfield marking the signer’s global index with a 1. When proofs are aggregated, their corresponding bitfields are combined using a bitwise OR operation. The resulting aggregate bitfield becomes a public input to the SNARK, ensuring the final proof attests to the precise claim: “the validators indicated by this specific bitfield have all provided valid signatures.”

Figure 1: Conceptual view of bitfield aggregation. Each signature corresponds to a bitfield marking the index of the signer (e.g., validators 0, 2, and 8). The aggregate signature is paired with a new bitfield created by taking the bitwise OR of the individual bitfields, providing a complete and compact record of all participants..

High-Level Design: \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate and \texttt{Merge}Merge

The system is built upon two core cryptographic operations that form the basis of the recursive construction. These operations allow the workload to be distributed and then progressively combined.

\texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate: This is the initial, non-recursive step. An aggregator node collects a batch of raw XMSS signatures from a subset of validators. It verifies each of these signatures individually and then generates an initial SNARK proof attesting to their collective validity. To verify these signatures and construct the correct bitfield, each \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate operation node must have access to the global validator registry. This registry, which maps each validator’s index to their corresponding public key, serves as a necessary public input. This operation transforms a set of large, expensive-to-verify signatures into a single, compact proof object.

\texttt{Merge}Merge: This is the recursive step. An aggregator node takes two existing proofs, each attesting to the validity of a distinct set of signatures, and combines them. The output is a new, single proof that provides the same cryptographic guarantee as if one had verified all the underlying signatures from both input proofs. This operation is the engine of scalability, allowing proofs to be combined efficiently.

To clearly explain the cryptographic process, we model the aggregation as a logical recursive tree, as illustrated in Figure 2. This tree structure is a useful abstraction because it allows us to distinctly analyze the two core cryptographic steps— \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate and \texttt{Merge}Merge —which are the fundamental building blocks of the proof system.

In practice, this logical model is implemented across a dynamic peer-to-peer (P2P) network. To manage high bandwidth requirements, the validator set is partitioned into multiple subnets. The process begins in parallel within these subnets, where initial proofs are generated from local sets of signatures using the \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate operation. As depicted in Figure 2, each Agg (Aggregate) operation shows its dependency on the Global State (Validator Registry). This indicates that an aggregator must query this global registry to obtain the public keys corresponding to the validators whose signatures it is verifying and to correctly update the aggregate bitfield for the generated proof. These initial proofs are then propagated throughout the network. As aggregator nodes receive proofs, they perform the \texttt{Merge}Merge operation, combining them to attest to progressively larger sets of validators. This distributed merging continues until a single, final proof is produced, which represents the attestations of the entire participating validator set.

Figure 2: The recursive aggregation process. Raw signatures (\sigma_iσi) are first processed by \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate operations, which access the global validator registry to verify them. These operations create initial proofs, which are then recursively combined by \texttt{Merge}Merge operations until a single, final proof is formed.

The important outcome of this design is that only the final proof is submitted to the blockchain. This single object, constant in size, replaces the need to process thousands of individual signatures on-chain. The chosen cryptographic paradigm must efficiently support both the \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate and \texttt{Merge}Merge operations. The fundamental architectural divergence, which we will explore next, lies in precisely how these two operations are implemented.

Path A: Brute-Force SNARK Recursion

The most direct architectural paradigm for implementing recursion is to place a full SNARK verifier inside another SNARK circuit. In this model, the \texttt{Merge}Merge operation is a SNARK that proves the verification of other SNARKs. This “proof-verifying-a-proof” method is a straightforward, albeit computationally intensive, way to achieve recursion.

Core Mechanism: Proofs Verifying Proofs

The fundamental task of the \texttt{Merge}Merge operation is to take two input proofs, \text{proof}_AproofA and \text{proof}_BproofB, and produce a new output proof, \text{proof}_{\text{out}}proofout, that attests to their validity. The relation being proven by the \texttt{Merge}Merge SNARK can be formally expressed as:

Here, VV represents the verification algorithm for the SNARK system. To generate \text{proof}_{\text{out}}proofout, the prover for the \texttt{Merge}Merge step must execute the entire logic of the verification algorithm VV for both input proofs within the arithmetic circuit of the new proof. This entails arithmetizing every cryptographic step of the verifier, including hash computations, polynomial commitment checks, and field arithmetic. Modern hash-based proof systems are well-suited for this, as their verifiers do not require expensive pairing operations.

The Role of the zkVM Abstraction

The primary challenge of this approach is the immense complexity of the verifier’s circuit. A verifier for a modern SNARK system involves a sophisticated sequence of cryptographic operations that translates into a massive and highly intricate constraint system. Building, auditing, and maintaining such a circuit by hand is practically infeasible and extremely error-prone.

This is where a Zero-Knowledge Virtual Machine (zkVM) becomes a practical necessity. A zkVM serves as an abstraction layer that manages this complexity, allowing developers to work with a familiar programming model instead of low-level circuit constraints. The process works as follows:

High-Level Logic: Instead of designing a circuit, a developer writes a program for the verifier’s logic using a simple, high-level Instruction Set Architecture (ISA). This program can express the logic for both the \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate and \texttt{Merge}Merge steps in a unified manner.

Cryptographic Precompiles: The zkVM is equipped with pre-compiled, highly optimized circuits for expensive cryptographic primitives. Operations like a \texttt{POSEIDON}POSEIDON hash permutation can be invoked as single, efficient instructions within the high-level program.

Compilation and Execution Trace: A compiler translates the high-level program into the zkVM’s bytecode. When this program is run, the zkVM’s prover generates a complete execution trace, which records every state transition of the VM—from instruction fetching to memory access. This entire trace is then automatically converted into the final, large-scale constraint system that is proven by the SNARK.

The \texttt{AggregateMerge}AggregateMerge Program Inside a zkVM

The zkVM model allows both the \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate and \texttt{Merge}Merge operations to be implemented within a single, unified program. A simplified version of such a program, which we can call \texttt{AggregateMerge}AggregateMerge, would take as public inputs the list of all validator public keys and the bitfield indicating which validators are being attested to in this step. As private inputs, it would receive a mix of raw XMSS signatures and existing SNARK proofs.

The program’s logic would then be to:

- Recursively verify the input proofs: For each inner proof provided, it calls the SNARK verification function (implemented using the zkVM’s instructions and precompiles).

- Directly verify the raw signatures: For each raw signature provided, it executes the XMSS signature verification algorithm.

- Check bitfield consistency: It ensures that the bitfields of the inner proofs and the indices of the raw signatures correctly combine to form the new, larger output bitfield.

The zkVM prover then generates a single SNARK proof for the entire execution of this \texttt{AggregateMerge}AggregateMerge program.

Performance Profile and Bottlenecks

The primary drawback of the zkVM-based approach is the significant computational overhead incurred by the prover. The prover is tasked not only with proving the application logic—the verification of signatures and proofs—but also with proving the correctness of the virtual machine’s execution itself. This VM overhead involves arithmetizing every internal step of the CPU, from instruction fetching and decoding to register updates, memory access, and control flow logic like jumps.

This additional workload makes each \texttt{Merge}Merge step computationally intensive and directly translates to higher latency, which can be a bottleneck in a time-sensitive P2P aggregation network. This stands in contrast to “fixed-program” recursion, where the verifier circuit is specialized for a single, predetermined program at compile time, eliminating the need for a general-purpose CPU architecture and its associated overhead.

However, it is crucial to note that the performance landscape for hash-based SNARKs is evolving rapidly. The “good enough” principle may apply if the raw performance of the underlying proof system is sufficiently high. Recent advancements in proving techniques are demonstrating extremely high throughputs. If these trends continue, the constant overhead of the zkVM may become an acceptable trade-off for the benefits in developer experience and flexibility, making it a viable option even in time-sensitive applications. Despite the high prover cost, modern hash-based SNARKs can produce very compact proofs, making it feasible to meet on-chain size targets.

Path B: Specialized Recursive Primitives

An alternative to brute-force recursion is to leverage cryptographic primitives designed specifically for this task: folding and accumulation schemes. Instead of verifying a complete SNARK within a circuit, this paradigm operates directly on the underlying mathematical statements of the proofs. It provides a highly efficient cryptographic shortcut that combines multiple computational integrity claims into a single, equivalent claim, significantly reducing the prover’s workload at each recursive step.

The Instance-Witness Framework

At the heart of this approach is the concept of an instance-witness pair, denoted as (x, w)(x,w), which represents a computational statement for a specific NP-relation RR. The instance xx contains the public data of the statement, while the witness ww contains the possibly secret data that satisfies it. This uniform structure is used for both the \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate and \texttt{Merge}Merge operations.

- The \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate Step: This operation creates the first instance-witness pair. The relation RR is the XMSS signature verification algorithm. The instance xx consists of public data (the message, the bitfield, and the relevant public keys), and the witness ww consists of the secret data (the raw XMSS signatures). The output is an initial instance-witness pair that is ready to be folded or accumulated.

- The \texttt{Merge}Merge Step: This operation takes two instance-witness pairs, (x_1, w_1)(x1,w1) and (x_2, w_2)(x2,w2), and uses a lightweight protocol to compute a single folded pair, (x_{\text{folded}}, w_{\text{folded}})(xfolded,wfolded), for the same relation RR. This process is computationally much cheaper than running a full SNARK verifier inside a circuit. Additionally, the folding prover is cheaper than a SNARK prover for the same relation.

We now explore two post-quantum mechanisms that implement this paradigm.

Lattice-Based Folding

A folding scheme is a protocol that takes two instances of a relation and combines them into a single new instance of the same relation. A prominent example of a post-quantum folding scheme is Neo, which is based on plausibly post-quantum lattice assumptions.

A key challenge in lattice-based cryptography is managing the norm of the witness. Performing cryptographic operations like linear combinations causes this norm to grow. If the norm grows too large, the security of the commitment scheme can break down. Neo is designed around a three-phase cycle that carefully manages this norm growth.

For our use case, the \texttt{Aggregate}Aggregate step creates an initial instance-witness pair for a relation called Matrix CCS (MCS), which represents the XMSS verification circuit. The \texttt{Merge}Merge operation then takes this new MCS instance and a running accumulator (which is an instance of a simpler evaluation relation, ME) and executes Neo’s cycle (Figure 3 depicts this workflow):

Figure 3: A visualization of Neo’s multi-folding scheme along with the finalization step to generate the on-chain SNARK.

Hash-Based Split Accumulation

Another primitive for recursion is a split accumulation scheme, which maintains a running accumulator that attests to the validity of a set of claims, which can even be for different relations. Split accumulation and folding schemes were introduced concurrently. Though there are some specific differences among them, they do not matter for our exposition. The \texttt{Merge}Merge operation corresponds to adding a new claim to this accumulator. A leading example of a post-quantum split accumulation scheme is WARP, which is based on plausibly post-quantum hash functions and is specifically designed for maximum prover performance.

The Split accumulation scheme

The core idea of a split accumulation scheme is to split the accumulator into two parts: a small, public instance part and a large, private witness part. At each recursive step, the prover (P_{ACC}PACC) takes the old accumulator and a new claim, produces an updated accumulator, and generates a small proof of this transition.

Crucially, the verifier (V_{ACC}VACC) only needs the public instance parts of the old and new accumulators to check this transition proof. The verifier never sees or processes the large witness part, making the recursive verification step extremely lightweight. The full witness is only required at the very end of the process by the final prover (the “decider”), who generates the single on-chain SNARK.

From Circuits to Polynomials: PESAT

In the WARP framework, the claims being accumulated are represented as instances of Polynomial Equation Satisfiability (PESAT). Instead of representing a computation as a circuit of gates, WARP represents it as a set of polynomial equations that must all evaluate to zero for a given instance and witness. This is a highly general framework that can capture common constraint systems like R1CS and CCS. For our use case, the XMSS signature verification algorithm and the bitfield logic are compiled into a PESAT instance.

A Linear-Time Prover

The primary advantage of WARP is its linear-time prover. The prover’s runtime, measured in field operations and hash computations, scales linearly with the size of the computation. This is a significant breakthrough for prover efficiency, avoiding two major sources of overhead found in other systems:

- The super-linear costs (O(N \log N)O(NlogN)) of group-based cryptography, which is dominated by large multi-scalar multiplications.

- The large constant overhead of a general-purpose zkVM, which must prove the execution of its own CPU architecture in addition to the application logic.

For a massive-scale, repetitive task like signature aggregation, a linear-time prover offers a profound performance improvement, making it a highly compelling option for the recursive engine.

Finalization: Generating the On-Chain SNARK

The recursive \texttt{Merge}Merge process, whether through folding or accumulation, results in a single, final instance-witness pair. This pair is computationally valid—it correctly represents the entire set of aggregated signatures—but it is not succinct in the traditional sense. The witness component is still present and required by the final prover, making the object too large for direct on-chain verification.

Consequently, the final aggregator node must perform an additional step: generate a standard, non-recursive SNARK of this final folded pair. This results in a hybrid architecture that employs two distinct cryptographic engines:

- The Recursive Engine: A folding or accumulation scheme selected for prover efficiency. Its primary purpose is to combine multiple statements into one with low computational cost at each recursive step.

- The Succinctness Engine: A final, non-recursive SNARK used to produce a compact and efficiently verifiable proof for on-chain use.

The finalization pipeline is as follows:

- The final folded instance-witness pair is treated as the statement to be proven.

- A Polynomial Interactive Oracle Proof (PIOP), such as (Super)Spartan, is applied to reduce the task of proving knowledge of the folded witness to a set of multilinear polynomial evaluation claims.

- A post-quantum Polynomial Commitment Scheme (PCS), such as BaseFold or WHIR, is used to prove the evaluations.

This hybrid architecture separates the function of efficient recursion from that of final succinctness. It leverages the respective advantages of each approach to build a system that is scalable and yields a compact on-chain proof.

The Engineering Challenge: Witness Management

A significant engineering challenge for this path is the management of witness data across the P2P network. The prover for any \texttt{Merge}Merge step requires access to the witnesses of the two proofs being combined. A naive implementation would require transmitting these large witnesses, which could create a substantial bandwidth bottleneck.

This issue can be addressed at the protocol level using a witness chunking technique. This approach mitigates the bandwidth requirements by altering how witnesses are handled:

Commitment to Chunks: A large witness is not treated as a monolithic object but is instead partitioned into multiple smaller, constant-size vectors. The prover then commits to each of these chunks individually.

Folding of Chunks: When two proofs are folded, the resulting folded witness is itself only a single, small vector. Consequently, the cryptographic state that must be passed between recursive steps remains compact and constant in size, preventing the compounding growth of data.

Efficient Verification: While this method increases the number of commitments the recursive verifier must process, schemes such as Neo are designed to handle this efficiently. The commitments to the witness chunks can be folded without introducing significant complexity or cost into the verifier circuit.

This design reframes the challenge from a cryptographic limitation to a P2P data availability problem: ensuring that aggregator nodes can locate and fetch the required witness chunks from the network to perform a \texttt{Merge}Merge operation.

Trade-Offs: Lattice vs. Hash-Based Primitives

The choice between a lattice-based folding scheme like Neo and a hash-based accumulation scheme like WARP involves architectural trade-offs, primarily centered on security assumptions versus performance and implementation complexity.

Security Assumptions: This is the main advantage of hash-based schemes. Their security relies only on the properties of a cryptographic hash function, typically modeled as a random oracle. This is a minimal and widely trusted assumption, though for folding/split accumulation. In contrast, lattice-based schemes rely on structured assumptions such as the Module Short Integer Solution (Module-SIS) problem. While strongly believed to be post-quantum hard, the practical security of specific lattice parameterizations is an active and evolving field of research. Ongoing advancements in cryptanalysis, such as practical improvements to hybrid attacks, continually refine our understanding of concrete security levels and introduce an element of long-term risk not present in simpler hash-based approaches.

Recursion Overhead: This is a key advantage of lattice-based schemes. The recursive `Merge’ step in a hash-based system requires verifying Merkle path openings within the next proof. In a lattice-based scheme, the folding operation is more algebraic, directly combining mathematical statements without verifying a full cryptographic object. This leads to a much simpler recursive verifier circuit, which can translate to significantly lower computational overhead.

Specialized Features: Lattice-based constructions like Neo can offer unique performance benefits. For example, Neo introduces “pay-per-bit” commitment costs, where the expense of committing to a witness scales with the bit-width of its values. This is highly advantageous for real-world computations where many witness values are small, a feature not typically found in hash-based systems that treat all data as full-size field elements for Merkle hashing.

A Comparative Analysis of Architectural Trade-Offs

The selection between brute-force recursion and specialized primitives involves distinct trade-offs in system design. The two approaches differ primarily in where they place complexity—either within the cryptographic proving infrastructure or at the peer-to-peer protocol layer—and consequently, in the balance between performance and developmental abstraction. The following table summarizes the key distinctions between these two architectural paths.

Table 1: Comparison of Recursive Aggregation Architectures

| Feature | Brute-Force SNARK Recursion | Specialized Primitives |

|---|---|---|

| Recursive Engine | Full SNARK verifier implemented within the circuit, resulting in a computationally intensive merge step. | Lightweight folding/accumulation algorithm that combines mathematical statements, not full proofs. |

| Prover Performance | Good, but incurs significant overhead from proving the zkVM’s execution in addition to the application logic. | Highly optimized. Avoids VM overhead, and schemes can offer linear-time proving or cost reductions via pay-per-bit commitments. |

| Circuit Complexity | Extremely high. The complexity of a SNARK verifier makes a zkVM abstraction a practical necessity for development and maintenance. | Low. The verifier for a folding/accumulation scheme is simple enough to be implemented directly and is amenable to formal verification. |

| Flexibility & Generality | High. A zkVM provides a general-purpose computational engine. An audited VM could be repurposed for other tasks, such as verifying different signature schemes or enabling privacy applications. | Low. The folding scheme is highly optimized for a specific relation (e.g., XMSS verification). Adapting it to another task would require significant new cryptographic engineering. |

| Locus of Complexity | Cryptographic Infrastructure: Resides in the zkVM compiler, prover, and associated toolchain. | P2P Protocol: Resides in the network layer responsible for witness data availability and management. |

| Final Proof Generation | Integrated. The output of the final Merge operation is already a succinct, on-chain verifiable SNARK. | Hybrid. The recursive process yields a non-succinct pair, which requires a final, separate SNARK generation step for on-chain use. |

| zkVM Necessity | High. A zkVM is essential to manage the immense complexity of the recursive verifier circuit. | Low. A zkVM is an optional tool for developer experience, not a requirement for managing cryptographic complexity. |

Conclusion

The transition to a post-quantum signature scheme for Ethereum’s consensus layer necessitates a recursive aggregation architecture. The choice of this architecture is not a simple decision: zkVM and folding schemes present each a unique profile of strengths and engineering challenges.

Path A, characterized by brute-force SNARK recursion, manages cryptographic complexity by abstracting it behind a zkVM. This approach simplifies the development of application logic but introduces significant, unavoidable computational overhead in the recursive step by requiring the prover to prove the VM’s execution trace.

Path B, which uses specialized primitives like folding and accumulation schemes, is designed for high performance by using a more efficient cryptographic engine for recursion. This design pushes complexity out of the cryptographic core and into the P2P protocol layer, which must then solve for challenges like witness data availability.

Ultimately, the optimal path for Ethereum is not yet determined and represents an active area of research. The decision will depend on the continued maturation of both zkVM and folding technologies, further analysis of P2P network dynamics, the precise performance and security requirements of the consensus layer, and a strategic choice on the long-term value of generality versus specialization. A zkVM-based solution, while potentially less performant for this one task, provides a flexible piece of infrastructure that could serve other future needs of the protocol, whereas a specialized folding scheme represents a highly optimized but potentially narrow solution. This article has aimed to clarify the fundamental trade-offs involved, providing a structured framework for the ongoing debate.