Author: Kalle Rosenbaum & Linnéa Rosenbaum

Source: https://bitcoindevphilosophy.com/#whenshithitsthefan

Bitcoin was developed by people. People write software, and then run that software. When security vulnerabilities or serious bugs are discovered—is there really a difference?—it's always people who discover them; from beginning to end, it's us, flesh and blood. This chapter considers what people did, should have done, and shouldn't have done when vulnerabilities were discovered. The first section explains the meaning of the term " responsible disclosure," which refers to how to act responsibly after a vulnerability is discovered to minimize the harm it causes. The remaining chapters will take you through some of the most serious vulnerabilities ever discovered in Bitcoin software, and how developers, miners, and users handled them. In Bitcoin's early days, many things weren't as robust as they are today.

9.1 Due Disclosure

Imagine you discover a bug in the Bitcoin Core software that allows someone to remotely shut down a Bitcoin Core node simply by sending a specially crafted message over the network. Now, suppose you have no malicious intent and don't want this vulnerability to be exploited. What would you do? If you remain silent, someone else might discover the vulnerability as well, but that person might not be as kind as you.

When disclosing a security issue, the person disclosing it should follow a responsible disclosure process. Bitcoin developers also frequently use this term; Wikipedia explains its meaning as:

Hardware and software developers often need time and resources to fix their bugs. Often, these vulnerabilities are discovered by ethical hackers [1]. Hackers and computer security scientists can choose to make raising public awareness of these vulnerabilities their social responsibility. Hiding the problem can create a false sense of security. To avoid this, the parties involved will coordinate and negotiate a reasonable window for vulnerability remediation. This window can range from a few days to several months, depending on the potential impact of the vulnerability, the expected time required to develop and implement emergency fixes or workarounds, and other factors.

— Wikipedia, "Responsible Disclosure" entry

This means that if you find a security vulnerability, you should report it to the team responsible for developing the system. But how does this work in the Bitcoin world? As described in Chapter 7.1 ( Chinese translation ), no one controls Bitcoin; there is only one focus of Bitcoin development: Bitcoin Core GitHub repository . The maintainers of this repository are responsible for the code within it, but they are not responsible for the entire Bitcoin system—nor is anyone else. Furthermore, the general best practice is to email security@bitcoincore.org .

In a 2017 email titled “Responsible Bug Disclosure,” Anthony Towns attempted to summarize what he considered best practices. He gathered input from multiple sources and different people to present his perspective on the topic.

- Vulnerabilities should be reported through the security page on the bitcoincore.org website [0].

- Critical vulnerabilities (those that can be exploited immediately, or those that have already been exploited and caused significant harm) will be handled as follows:

- Release the patch as soon as possible

- Widespread notifications indicate the need for upgrades (or disabling of affected systems).

- Disclose as few actual problems as possible to delay the attack [1][2]

- Non-critical vulnerabilities (because they are difficult or expensive to exploit) will be handled as follows:

- Patch and review in the standard development process.

- Porting fixes or workarounds from the master branch to the current release [2]

- Developers will attempt to release a fix without revealing the nature of the vulnerability. The approach is to provide the proposed fix to experienced but unaware developers, informing them that a vulnerability has been fixed and requesting them to locate the vulnerability. [2]

- Before a fix is issued and widely adopted, developers can suggest that other Bitcoin implementations adopt the fix if it can prevent the vulnerability from being exposed; for example, if the fix has significant performance advantages, it can be a reason to merge these codes [3].

- Before the vulnerability is revealed, developers will generally advise friendly Altcoin developers to follow up on the fix. However, this will only be possible after the fix has been widely deployed in the Bitcoin network. [4]

- Developers generally do not notify Altcoin developers who have previously shown hostility (e.g., by using vulnerabilities to attack others, or by violating prohibitions) [5].

- Bitcoin developers will not disclose vulnerabilities until more than 80% of Bitcoin nodes have deployed a fix. Vulnerability disclosers will be encouraged and required to follow the same strategy [1][6].

— Anthony Towns, “Due Disclosure of Bugs” mailing list, Bitcoin-dev mailing list (2017)

The above list illustrates how cautious one should be when releasing patches for Bitcoin, as patches can reveal the location of vulnerabilities. The fourth point is particularly interesting because it explains how to test if a patch is well-hidden. In fact, if even a few experienced developers cannot locate a vulnerability when they know it's a fix, it can be very difficult for others to find it.

Prior to this email, the discussion in the email thread revolved around whether, when, and how to disclose vulnerabilities to Altcoin developers and other Bitcoin implementation developers. There were no definitive answers. "Helping good people" seems reasonable, but who can be sure they aren't good people? Where is the line drawn? Bryan Bishop argues that helping Altcoin, even fraudulent ones, protect themselves from security breaches is a moral responsibility.

Protecting Bitcoin and its users from immediate threats is not enough; there is a broader responsibility to protect all types of users and different software from a wide variety of threats of whatever form they may take, even if those users are using stupid and insecure software that you personally do not maintain, develop, or recommend using. Dealing with knowledge of a vulnerability is tricky, and you may receive knowledge with more serious direct or indirect consequences than its initial description.

— Bryan Bishop, “Due Disclosure of Bugs” mailing list, Bitcoin-dev mailing list (2017)

The Towns email was preceded by an email from Gregory Maxwell, in which he argued that the security vulnerability might be more serious than it appeared.

I have seen many times how a problem that was initially considered difficult to exploit turns out to be quite easy to exploit, provided you find the right agency; or how a minor DoS problem turns out to be a much more serious problem.

Even a simple performance bug, if carefully deployed, can be used to disrupt a network—miner A and exchange B are on one network, while others are on another, allowing someone to spend repeatedly.

And so on. So, while I absolutely agree that different things should (and can) be handled differently, the lines aren't always so clear. The main thing is to be cautious about thinking the problem is more serious than you already know it to be.

— Gregory Maxwell, “Due Disclosure of Bugs” mailing list, Bitcoin-dev mailing list (2017)

Therefore, even if a vulnerability seems difficult to exploit, it's best to assume it's easy to exploit—you just haven't figured out how to exploit it yet.

Gregory also noted, "It's incorrect to think this email thread is discussing 'disclosure.' Disclosure refers to telling a supplier. This email thread is about 'public disclosure,' and the implications are different. Public disclosure means you're certain you've also told a potential attacker." This last observation, regarding the difference between disclosure and public disclosure, is important. Responsible disclosure is the simpler part; reasonable public disclosure is the difficult part.

9.2 Childhood trauma

Bitcoin was initially a personal project (at least, judging from the pseudonym of its creator, it was one person), and at that time, Bitcoin had almost no value. Therefore, the disclosure of vulnerabilities and the fixing of bugs were not as rigorous as they are now.

The Bitcoin Wiki maintains a list of publicly disclosed vulnerabilities (CVEs) that have affected Bitcoin. This chapter will introduce some of these security vulnerabilities, as well as some unexpected incidents that occurred in Bitcoin's early days. We will not cover all vulnerabilities, but only those we find particularly interesting.

9.2.1 2010-07-28: Spending anyone's money (CVE-2010-5141)

On July 28, 2010, an anonymous user using the pseudonym "ArtForz" disclosed a vulnerability in bitcoin software version 0.3.4 that allowed anyone to spend other people's coins. ArtForz dutifully reported this vulnerability to Satoshi Nakamoto and another developer named "Gavin Andresen".

The problem is that the script opcode OP_RETURN at the time would immediately terminate the program's execution. Therefore, if the script public key for the spent coins was <pubkey> OP_CHECKSIG , and the script signature was OP_1 OP_RETURN , the program in the script public key would not execute at all. The only thing that would happen is that 1 is pushed into the game, and then OP_RETURN causes the program in the script public key to be skipped. After the program finishes executing, any non-zero value at the top of the stack means that the spending condition has been met. Because the element at the top of the stack is 1 , not 0 , the spending succeeds.

This is the code that handled OP_RETURN at that time:

case OP_RETURN: { pc = pend; } break; The effect of pc = pend; is to skip the rest of the program, meaning any locked scripts in the script's public key will be ignored. One fix is to change the meaning of OP_RETURN so that it immediately outputs (script execution) failure.

case OP_RETURN: { return false; } break;Satoshi Nakamoto made this change in his own codebase and then compiled an executable binary using version number 0.3.5. He then posted on the Bitcointalk forum, "WARNING! Upgrade to 0.3.5 ASAP (***** ALERT *** Upgrade to 0.3.5 ASAP)," urging users to install the binary, but without providing its source code.

Please upgrade to version 0.3.5 immediately! We've fixed an implementation bug that allowed fraudulent transactions to be accepted by the network. Do not accept any Bitcoin payments until you upgrade to version 0.3.5!

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcointalk forum (2010)

The original message was edited, and its complete form is now unknown. The above excerpt comes from a quoted reply . Some users tried Satoshi Nakamoto's binary but encountered problems running it. Soon after, Satoshi Nakamoto said :

SVN hasn't been updated yet. Please wait for version 0.3.6, which I'm currently developing. You can shut down your node in the meantime.

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcointalk forum (2010)

(Translator's note: "SVN" here should refer to "Apache Subversion," an open-source version control system.)

35 minutes later, he said :

SVN has been updated in version 0.3.6.

I'm uploading the Windows executable (version 0.3.6) to Sourceforge, and then I'll recompile the Linux executable.

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcointalk forum (2010)

(Translator's note: "Sourceforge" is a website where you can upload code for others to download.)

At this point, he also seemed to have updated his original post, changing "0.3.5" to "0.3.6":

Please upgrade to version 0.3.5 immediately! We've fixed an implementation bug that allowed fraudulent transactions to potentially appear as accepted. Do not accept any Bitcoin payments until you upgrade to version 0.3.5!

If you are unable to upgrade to 0.3.6 now, it is best to shut down your Bitcoin node, upgrade, and then restart it.

Version 0.3.6 also implements faster hash operations:

- Thanks to tcatm, the optimization of intermediate state caching was implemented.

- Thanks to BlackEye for adding Crypto++ ASM SHA-256.

The final acceleration effect is 2.4 times.

Download page:

http://sourceforge.net/projects/bitcoin/files/Bitcoin/bitcoin-0.3.6/

Windows and Linux users: Even if you have version 0.3.5, you still need to upgrade to version 0.3.6.

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcointalk forum (2010)

Please note the different wording in the two messages: the first one says "(The fake transaction) was accepted by the network," while the second says "It was displayed as accepted." Perhaps Satoshi Nakamoto downplayed the severity of the problem to avoid drawing attention to the real issue. In any case, those who upgraded to version 0.3.6 can use Bitcoin normally. The problem is solved, and remarkably, no one lost their Bitcoin.

Satoshi Nakamoto's message also mentioned performance optimizations for mining. It's unclear why this would be included in a critical security fix, but it's possible it's intended to obscure the real issue. However, it seems more likely that he simply released something on a development branch of the Subversion codebase (whatever that thing was) and added the security fix.

Back then, there were far fewer Bitcoin users than there are today, and Bitcoin had virtually no value. If they were to handle bugs like this today, it would be considered a major soap opera.

- Satoshi Nakamoto released version 0.3.5, which consisted only of binary files and included the fixes. The lack of a patch and source code could be seen as a way to obfuscate the issue.

- Version 0.3.5 is not even able to run .

- The fix in 0.3.6 is actually a hard fork, as explained in section 5.2 ( Chinese translation ).

Another debatable issue is whether allowing users to disable their own nodes was a good thing or a bad thing. It's impossible to do that today, but back then, many users actively followed forum updates and were often quite knowledgeable. Therefore, it was possible then, and perhaps a reasonable measure.

9.2.2 August 15, 2010: Merged output value overflow (CVE-2010-5139)

In mid-August 2010, a Bitcointalk forum user named "jgarzik," also known as Jeff Garzik, discovered that two outputs of a transaction in block height 74638 possessed rare high value:

The "output" in block #74638 is very strange:

"out" : [ { "value" : 92233720368.54277039, "scriptPubKey" : "OP_DUP OP_HASH160 0xB7A73EB128D7EA3D388DB12418302A1CBAD5E890 OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG" }, { "value" : 92233720368.54277039, "scriptPubKey" : "OP_DUP OP_HASH160 0x151275508C66F89DEC2C5F43B6F9CBE0B5C4722C OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG" } ]92233720368.54277039 BTC? Isn't that just the maximum value of UINT_64 (unsigned 64-bit integer)?

— Jeff Garzik, Bitcointalk forum (2010)

It's highly likely that this is a bug causing the sum of the two output values—which are int64 (signed 64-bit integers) instead of uint_64 as Garzik expected—to overflow into a negative value of -0.00997538 BTC. Therefore, regardless of the input value, the output sum is always smaller, making it a valid transaction according to the code at the time.

In this context, the bug was made public by a real blitz. The unfortunate thing about this blitz was that approximately 2 x 92 billion BTC were created, severely diluting the then-current money supply of only about 3.7 million BTC.

In a related post, Satoshi Nakamoto stated that he would be grateful if someone could stop mining (then called " generating ").

It would help if people could stop producing. We might need to mine another branch of the blockchain; the slower people produce on the current branch, the faster we can build the other branch.

The first patch will be in SVN rev 132. It hasn't been uploaded yet. I'm still pushing in some miscellaneous changes that need to be completed first, and then I'll upload the patch.

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcointalk forum (2010)

His plan was to create a soft fork to invalidate transactions like the ones mentioned above, thus invalidating blocks containing such transactions (especially the block at height 74638). Less than a month later, he submitted a patch in revision 132 of the Subversion codebase and posted on the forums about what he believed users should do:

The patch has been uploaded to SVN rev 132!

For now, the recommended steps are:

1) Shut down the node.

2) Download the "knightmb" blk file (to replace your blk001.dat and blkindex.dat files).

3) Upgrade the software.

4) The software will start synchronizing from fewer than 74,000 blocks. Let it re-download the remaining blocks.

If you don't want to use knightmb's files, you can directly delete your blk*.dat files (files starting with "blk" and containing ",dat" characters). However, if everyone downloads all the blocks at the same time, it will put a heavy burden on the network.

I will compile and release the version soon.

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcointalk forum (2010)

He wanted people to download the block data from a specific user ("kinghtmb"): this user published the blockchain that appeared on their hard drive, namely the blkXXXX.dat and blkindex.dat files. The rationale for downloading the block data in this way (instead of resynchronizing from scratch) was to reduce network bandwidth bottlenecks.

Here's a major problem: blocks downloaded by users from knightmb are not verified when the Bitcoin software starts; the blkindex.dat file already contains the UTXO set, and the software directly accepts any data from it as verified. knightmb could tamper with the data, artificially adding Bitcoins for himself or others.

(Translator's note: This possibility does exist; however, it will be exposed once the user runs the software with the reindexed startup option. Ultimately, although the software will not automatically re-verify upon startup after the user replaces these two files, the user can still make the software re-verify.)

Once again, it seems the advice was heeded, and the rollback of the invalid block and its descendants was successful. Miners began mining after the original block at height 74637 , and the first subsequent block appeared at 23:53 UTC, approximately six hours after the issue was discovered. By 08:10 the following day (August 16th), at block height 74689, the new chain replaced the old one, and all nodes with outdated software were reorganized to follow the new chain. This was the deepest block reorganization in Bitcoin history—reaching 52 blocks.

Compared to the problems caused by OP_RETURN, this approach is arguably much smarter:

- A patch that includes more than just binary files was released.

- The work on the newly released software is in line with expectations.

- No hard fork

During the issue resolution, users were asked to stop mining. We can discuss whether this is a good idea, but suppose you are a miner and you have been convinced that blocks mined after bad blocks will eventually be destroyed in a deep blockchain reorganization: then why waste resources mining those blocks?

You might also think that Satoshi Nakamoto's suggestion—to download the blockchain and UTXO sets from a stranger's hard drive—is somewhat plausible. If so, you're right: it is indeed questionable. However, in that situation, such an emergency response is also reasonable.

This incident differs significantly from the OP_RETURN incident in that this vulnerability was actually exploited, allowing for a more direct fix. In the OP_RETURN incident, developers had to obscure the fixes, and public statements couldn't directly reveal the problem.

9.2.3. 2013-03-11 DB Lock Issue 0.7.2 - 0.8.0 (CVE-2013-3220)

A very interesting and educational issue arose in March 2013. At that time, the blockchain appeared to have split after height 225429 (which is what the "fork" in the following quote means). Details of this incident are disclosed in BIP50 . The document summarizes it as follows:

In a block that was mined and broadcast, the total number of transaction inputs exceeded the previously observed maximum. Bitcoin 0.8 nodes could process this block, but some Bitcoin nodes from versions prior to 0.8 (pre-0.8) rejected it, leading to an unexpected blockchain fork. The chain incompatible with 0.8 and earlier versions (hereinafter referred to as the "0.8 chain") then concentrated 60% of the mining power, making this split impossible to resolve automatically (if the pre-0.8 chain's hash power could defeat the 0.8 chain, it would force the 0.8 nodes to regroup onto the pre-0.8 chain, thus resolving the split automatically).

To restore a recognized blockchain as quickly as possible, BTCGuild and Slush downgraded their node software from Bitcoin 0.8 to 0.7, causing their mining pool to reject the larger block. This allowed the majority of the computing power to return to the chain without the larger block, ultimately enabling the 0.8 nodes to reorganize onto the pre-0.8 chain.

— Several Bitcoin Core developers, BIP50 (2013)

The swift action taken by the BTCGuild and Sluch mining pools during this crisis was impressive. They were able to transfer the majority of their hash power to the split pre-0.8 branch, thus helping to rebuild consensus. This gave developers time to develop sustainable fixes.

Another equally interesting issue in this case is that version 0.7.2 is incompatible with itself, as are previous versions. This is explained in the "Root Cause" section of BIP50 :

This insufficient BDK lock configuration implicitly becomes a network consensus rule for determining the validity of blocks (although this is an inconsistent and insecure rule, as the amount of lock used may differ on different nodes).

— Several Bitcoin Core developers, BIP50 (2013)

In short, the problem is that the number of database locks used by the Bitcoin Core software to verify blocks is not deterministic. One node might need X locks, while another node might need X+1 locks. There's also a limit to the number of locks a node can hold for a block. If the required number of locks exceeds this limit, the block will be considered invalid. So, if X+1 exceeds the limit, but X doesn't, the two nodes will split into two branches, each disagreeing on which branch is valid.

In addition to the emergency actions taken by the two major mining pools mentioned above, the final selected solutions also included:

- In version 0.8.1, blocks are restricted not only in size but also in the number of locks they contain.

- Patches older versions (0.7.2 and some older versions) to use the same new rules, while also increasing global lock restrictions.

In addition to increasing the global lock limit as mentioned in point two, these rules are implemented as temporary rules, used within a predetermined time window. The plan is to remove these limits once the vast majority of nodes have been upgraded.

This soft fork significantly reduced the risk of consensus failures, and a few months later, on May 15th, the temporary rules were uniformly deactivated across the entire network. Note that this deactivation was essentially a hard fork, but without controversy. Furthermore, it was released alongside the previous soft fork, so anyone running software after the soft fork knew this hard fork would follow. Therefore, when this hard fork activated, the vast majority of nodes remained synchronized. However, a small number of nodes that had not upgraded were still pushed off the network during this process.

You might wonder: if this happened today, would we still be able to handle it this way? The mining landscape is much more complex now; both sides of a split might have hash power, making it difficult to release patches as quickly as BIP50. Convincing miners on the "wrong" branch to give up their block rewards would also be challenging.

9.2.4 BIP66

BIP66 is interesting because it demonstrates the importance of the following:

- Good selective cryptography

- Due Disclosure

- Deploy fixes without revealing vulnerabilities

- Mining on verified blocks

BIP66 was a proposal to tighten the encoding rules for signatures placed in the Bitcoin script. The motivation for the proposal was to enable signature parsing using software and code libraries other than OpenSSL (previously, you could only use the latest version of OpenSSL). OpenSSL is a general-purpose cryptography code library; at that time, Bitcoin Core still used it.

This BIP was activated on July 4, 2015. However, in addition to the completely accurate content mentioned above, BIP66 also fixed a much more serious problem that was not mentioned in the original BIP.

Vulnerability

This vulnerability was not fully disclosed until July 28, 2015, by Pieter Wuille in an email sent to the Bitcoin-dev mailing list :

Hello everyone,

I wish to disclose a vulnerability that I discovered in September 2014; it has become unexploitable after BIP66 deployment reached the 95% threshold earlier this month.

Brief description

A specially crafted transaction could cause the blockchain to split among the following three types of nodes:

- Nodes using OpenSSL on 32-bit and 64-bit Windows systems

- Nodes using OpenSSL on non-Windows 64-bit systems (Linux, OSX, etc.)

- Use some non-OpenSSL codebases to parse the signature node

— Pieter Wuille, “Disclosure: A consensus bug directly resolved by BIP66”, Bitcoin-dev mailing list (2015)

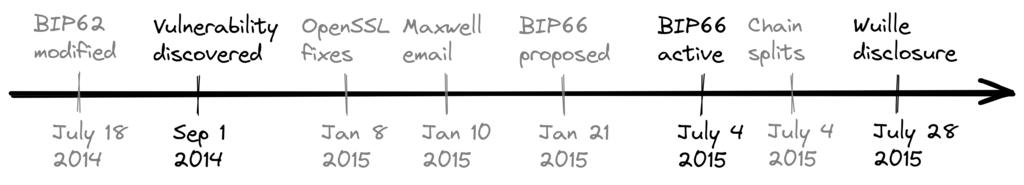

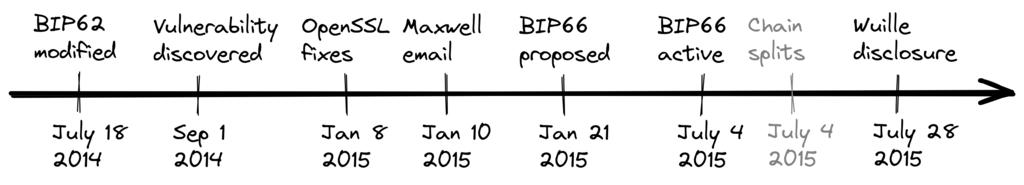

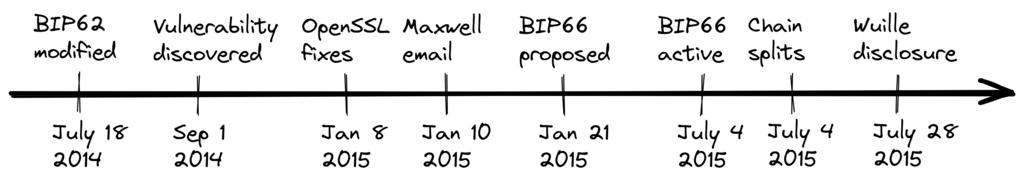

The email further details the discovery of the vulnerability and the more specific reasons that led to it. Finally, Pieter provides a timeline of events; we will review some of the most important events, as shown in Figure 13, some of which have already been discussed.

Figure 13. Chronological order of events surrounding BIP66. The bolded parts have been discussed above.

Before disclosure

Before anyone knew about this problem, it could have been solved by BIP62, which has since been withdrawn: this BIP reduced the likelihood of transaction malleability. One of the changes proposed in BIP62 was tightening the consensus rules regarding signature encoding, also known as "strict DER encoding." Pieter Wuille proposed some adjustments to this BIP in July 2014 that could solve this problem:

- July 18, 2014: To make Bitcoin's signature encoding rules independent of specific OpenSSL parsers, I modified the BIP32 proposal so that its strict DER signature requirements also applied to transactions with version number 1. At that time, no non-DER signatures were going to enter the block, so it could be assumed that it wouldn't directly affect anyone. See https://github.com/bitcoin/bips/pull/90 and http://lists.linuxfoundation.org/pipermail/bitcoin-dev/2014-July/006299.html for details. It was unknown at the time, but if BIP66 were deployed, this vulnerability would be resolved.

— Pieter Wuille, “Disclosure: A consensus bug directly resolved by BIP66”, Bitcoin-dev mailing list (2015)

Because this BIP's coverage was too broad, far exceeding the "strict DER coding" aspect, it was constantly being revised and its deployment was delayed. Later, this BIP was networked because "Segregated Witness" BIP141 addressed the transaction meltdown problem in a more complete way.

After disclosure

OpenSSL has released a new version of its software with patches; using these patches (the new software) in the Bitcoin software from the beginning would resolve the issue. However, simply using the new version of OpenSSL in a new version of Bitcoin Core would worsen the problem. Gregory Maxwell explained this in another mailing list in January 2015:

While it's generally acceptable to vehemently reject certain signatures for most applications, Bitcoin is a consensus system, meaning all participants must generally agree on the validity or invalidity of input data. In other words, consistency is more important than "correctness."

...

However, the patch above only fixes one symptom of this widespread problem: the consensus specification's behavior relies on software (especially OpenSSL) that is not designed and distributed for consensus purposes. Therefore, as an incremental improvement, I propose enforcing stricter DER compatibility as soon as possible with a dedicated soft fork, using only a subset of BIP62.

— Gregory Maxwell on OpenSSL upgrades, Bitcoin-dev mailing list

He pointed out that using code that is not intended to serve in the consensus system poses serious risks and proposed that Bitcoin implement strict DER encoding. This is an excellent example of the importance of selective cryptography—which we discussed in Chapter 7.4 ( Chinese translation ).

These events might give you the impression that Gregory Maxwell knew about the vulnerability Pieter Wuille later revealed, but wanted to cover it up under the guise of "prevention" to avoid drawing too much attention to the real issue. That's possible, but it's all just speculation.

Then, as Maxwell proposed, BIP66 was put forward as a subset of BIP62, specifying only strict DER encoding. This BIP was apparently widely accepted and deployed in July; however, ironically, it still resulted in two blockchain splits due to "validationless mining ." These splits will be discussed in the next section.

This leads to a key conclusion: a BIP should be more or less atomic , meaning it should be complete enough to provide something useful or solve a specific problem, but small enough to be widely pointed out by users. The more you put into a BIP, the less likely it is to be accepted.

Blockchain splits due to unverified mining

Unfortunately, the story of BIP66 doesn't end there. The activation of BIP66 proved extremely chaotic, as some miners didn't verify blocks upon receiving them but instead started mining immediately afterward. This is called "no-verification mining," or "SPV mining" (SPV stands for "Simplified Payment Verification," which only verifies the block header). A warning message was sent to Bitcoin nodes, along with a webpage describing the problem :

In the early morning of July 4, 2015, (BIP66) had reached the 950/1000 (95%) threshold. However, shortly afterward, a small miner (one of the 5% that hadn't upgraded) mined an invalid block—as expected. Unfortunately, it turned out that roughly half of the network's mining power was mining with an incomplete block verification setting (called "SPV mining"), thus mining new blocks after this invalid one.

— Warning message from Bitcoin Core developers on bitcoin.org (2015)

This warning page instructs users that if they are using an older version of Bitcoin Core , they should wait an additional 30 blocks for confirmation on top of the usual voluntary block confirmation requirement.

The aforementioned split occurred on July 4, 2015, at 02:10 UTC, after block height 363730. The issue was resolved at 03:50 that day—after six invalid blocks were mined. Unfortunately, the same problem occurred again the following day: at 21:50 on July 5, but this time, the invalid branch lasted only three blocks.

The events that led to the creation and deployment of BIP66, and the subsequent events, provide an excellent case study, revealing why Bitcoin developers must exercise caution. Some key conclusions from the BIP66 incident:

- Finding a balance between openness and non-disclosure of vulnerabilities is a delicate matter.

- Deploying fixes for undisclosed vulnerabilities is a tricky game.

- Maintaining consensus is not easy.

- Software that is not intended to serve in a consensus system often poses risks.

- BIPs should be atomized to some extent.

9.3 Conclusion

Bitcoin has bugs. Those who discover bugs are encouraged to responsibly disclose them to Bitcoin developers so they can fix them before they become public. Ideally, the fix can be disguised as a performance improvement or some other smokescreen.

We reviewed some of the more serious vulnerabilities that surfaced over the years, and the actions taken to address them. Some vulnerabilities were exposed because they were exploited, while others were dutifully disclosed and patched before malicious actors had the opportunity to exploit them.