Hyperliquid is a highly prominent perpetual futures exchange covered heavily in the web3 press and doing a lot of volume. It calls itself decentralized but, as is so often the case, this is not true for any reasonable definition of “decentralized.” The system is officially closed-source which, by itself, is a red flag for something that is supposedly transparent and open for everyone to use. But we do not even need to leak the source code here to establish the team exercises total independent control over user funds.

There is no need to dig deeply into the “Hyperliquid L1” that hosts their perpetual futures trading platform. We can work out everything we need to prove the team completely controls the platform by looking at a few smart contracts for which the source code is already publicly available. As is usually the case this all revolves around how the team, and the team alone, can execute an attack to expropriate substantially all user funds.

So now we are going to do that. We start with an overview of how the platform works with particular focus on their bridge. Then we provide a bit of data that serves as a bridge between a discussion of architecture to a discussion of centralization. And then we conclude with a few remarks on the legal situation.

How Hyperliquid Works

While the core Hyperliquid code is closed-source we do have access to their bridge contract on Arbitrum and this gives us a lot of information about how Hyperliquid works. In particular we can prove the following:

- The bridge does not rely on a ZK design and in fact it is not trustless at all.

- There is a dispute resolution mechanism.

- It is not a validium because there is a dispute period. And it is not a ZK design. So presumably it is similar to, or some kind of, optimistic roll-up.

- Security mainly depends on maintaining secrecy because the dispute period is 200 seconds. Consider that 200 seconds is the amount of time available to take extraordinary action if needed to secure about US$6 billion. Compare that to Arbitrum and Optimism which both have dispute periods of about 1 week.

- The Hyperliquid team actively administers the bridge.

- The Hyperliquid team must approve all withdrawal requests.

- The validator set on the closed-source Hyperliquid chain is not linked, or at least not closely linked, to the validator set recognized by the bridge. Hyperliquid habitually abuses vocabulary on this front.

Finally note that while a 200 second dispute period sounds short it’s not like anyone external can use the dispute process. What are you going to dispute if there is no spec against which to measure things? Some of this “technology” is a bit of a joke.

Bridge Design

We can only see the code for the Arbitrum side of Hyperliquid’s bridge. So the simplest way to analyze the product is to observe how the Arbitrum side behaves.

The bridge emits a ChangedDisputePeriodSeconds event with a newDisputePeriodSeconds field when the dispute period is changed. This tells us, among other things, that there is a dispute period and presumably some dispute resolution process. And we know this dispute period is enforced because the bridge has emitted a FailedWithdrawal event with errorCode 4. If you look in the code you find, inside getDisputePeriodErrorCode():

bool enoughBlocksPassed = (curBlockNumber - blockNumber) * blockDurationMillis > 1000 * disputePeriodSeconds;

if (!enoughBlocksPassed) {

return 4;

}

So the failed withdrawal with error code 4 is a situation in which a withdrawal was rejected because it was requested too quickly. The existence of a dispute period tells us the design is not pure ZK as there is no need for dispute resolution if withdrawals are gated by ZK proofs of ownership. While we cannot speak directly to the design of Hyperliquid itself, this strongly suggests it is not a ZK-based design.

The bridge also has a peculiar dispute resolution process that works as follows:

- A withdrawal is requested and the dispute period begins.

- The administrator can call invalidateWithdrawals() to block pending withdrawals.

- After the dispute period ends any still-valid withdrawals can proceed.

This is not dispute resolution as much as it is a blunt form of centralized control. In l2beat terms this is stage 0. For anyone not familiar with the l2beat’s staging vocabulary this means l2beat would classify Hyperliquid as centralized and with “training wheels” were it counted as an L2.

As we will see below the Hyperliquid team operates these processes off-chain and none of the management is autonomous. While Hyperliquid is automated with software it is automated in the same way all bank software is automated: with human-level controls and an Oz-like operator behind the curtain. In l2beat terms this is also a stage 0 characteristic. We are not breaking new ground here but simply applying broadly-accepted frameworks and definitions to a product with many familiar pieces.

What Kind Of Thing Is Hyperliquid

Hyperliquid calls itself a layer-1 blockchain. Given all the assets come from a single bridge contract on Arbitrum, which is an Ethereum Layer-2 blockchain, it is in some sense a layer-3. And we know from the above analysis that it is not a ZK rollup or validium. So what is it?

This leaves us with few options. It might be some kind of optimistic rollup, or some flavour of plasma chain. Or maybe some kind of sidechain. It could also be some sort of hybrid of those kinds of schemes. But notice that while there is a dispute process there is no public specification for how this stuff works or exactly what one would dispute.

Even if the process is a bog-standard optimistic rollup nobody but the team can dispute anything so none of that really matters. In practice this is just a stage-0 layer-3 blockchain with full team control. The software — which, again, is mostly closed-source — may have the data structures and function names of a plasma or sidechain or whatever but in reality it is just a custodial multisig with some unnecessary code around the edges.

From the team’s perspective that code may be necessary. The team may be very proud of that code. But for an external observer none of that matters because these things live inside a walled garden. When a researcher is forced to guess how parts of hyperliquid work to do analysis there is already a hint of trouble. But in theory one might have an autonomous decentralized system that is also a black box. Users can, at least mechanically, sign up to accept the results of a process they cannot see or understand.

It is admittedly unclear how enforceable such a contract would be for a futures exchange but drafting the docs is easy enough. But as we are exploring here we can see administrators taking administrative actions on the black box. That changes things. Now the burden of proof is on those administrators to show they do not have central control. Or, as is the case here, we can provide pre-emptive proof that blocks any such claim.

Bridge Administration

We can see the Hyperliquid team calling the following 5 admin functions on the bridge contract that do what their names suggest:

- changeDisputePeriodSeconds()

- modifyFinalizer()

- modifyLocker()

- voteEmergencyLock() which emits a “Paused” event

- emergencyUnlock() which emits an “Unpaused” event

The bridge also maintains validator set information that can be manipulated by the Hyperliquid team using the updateValidatorSet() and finalizeValidatorSetUpdate() functions. Maintenance was done on the validator set in December 2023 and October 2024. Then on April 22, 2025, the Hyperliquid team announced they were expanding the validator set but there were no corresponding RequestedValidatorSetUpdate and FinalizedValidatorSetUpdate events emitted.

This means the validator set known by the bridge did not change at the same time. Months later, the validator set has not been updated, proving the (trusted) synchronization of validator sets between the Hyperliquid blockchain and bridge is not necessary. There seems to be a gap between public statements about the validator set and use of the functions which manipulate the validator set.

This is a flashing red sign that vocabulary is abused here. There is a validator set for the Arbitrum-hosted bridge contract. And there is a validator set for the Hyperliquid platform. By comparing the history of updates of those two sets we can tell they need not be the same. There are two different “validator set” concepts here. Even if Hyperliquid tells us they are the same we can see for ourselves that they are not kept synchronized.

The Team Approves Withdrawals

If we look at bridge contract activity we see a long stream of the following function calls:

- batchedDepositWithPermit()

- batchedRequestWithdrawals()

- batchedFinalizeWithdrawals()

The deposit process initiates a transfer from the depositor to the bridge. If the depositor has sufficient funds for that to work the deposit is registered. That workflow is simple.

But the withdrawal process is significantly more complex. For a withdrawal to be successful it must be both requested and then finalized, and both steps require signatures by a sufficient number of system “validators.” The list of validators is controlled by the administrative functions on this bridge that are discussed above. These are the Arbitrum-side validators that we already know are not synchronized with the Hyperliquid blockchain.

Deposits are user-initiated and do not require the central Hyperliquid entity and that entity’s software to play along. Over 300 addresses have initiated deposits since the system launched. Withdrawals, on the other hand, are batched up for requesting and then finalization exclusively by the team. 4 Hyperliquid-controlled addresses are responsible for all withdrawal requests and finalizations with roughly 200 thousand invocations of each per address as-of the preparation of this data in mid 2025. These addresses are:

| Address |Requests |Finalizations|

|-------------------------------------------|---------|--------|

|0x58e1b0e63c905d5982324fcd9108582623b8132e | 201,581 | 194,557|

|0xef2364db5db6f5539aa0bc111771a94ee47637fc | 201,779 | 194,418|

|0x263294039413b96d25e4173a5f7599f8b3801504 | 201,294 | 194,508|

|0xda6816df552c3f9e0fb64979fb357800d690d79b | 200,921 | 195,196|

These addresses were added as validators by the also-clearly-team-controlled address 0x1D4c01E15A637cB3cbaF86fFbb02E5A260D01fbc. All of this can be derived from public sources and does not require anything from the closed-source futures exchange side of the system.

We know these must all be the team because those are all of the withdrawal requests processed since launch. These are not addresses added some weeks or months post-launch during some progressive decentralization process or anything like that. These addresses are all there is. If there is a team — and there clearly is — these are properly viewed as part of that Hyperliquid team because they are the only addresses that have ever gated withdrawals.

Each of these requests will only be accepted by the bridge contract if it includes signatures from a sufficient number of validators. And the current validator set is controlled, again, by team-linked addresses. The only limit on team control is that administrative updates are subject to a dispute period during which changes cannot be finalized. That dispute period is 200 seconds. If the team decided to go rogue there would be a sort of 200 second period in which someone, somewhere, in theory might be able to request withdrawals or attempt to submit a request to invalidate something. Except this process is not open to the public either. Only validators can stop this. Again the “dispute” process is a charade and this is all just a big multisig.

So we now know the withdrawal functions are exclusively gated by team validator addresses on Arbitrum. While the above analysis proves this conclusively it is not well hidden. The team’s validator addresses on Hyperliquid are publicly documented and the same names using different addresses are publicly tagged as validators on the Arbitrum side:

- 0xef2364db5db6f5539aa0bc111771a94ee47637fc

- 0xda6816df552c3f9e0fb64979fb357800d690d79b

- 0x58e1b0e63c905d5982324fcd9108582623b8132e

- 0x263294039413b96d25e4173a5f7599f8b3801504

and have run the system since the addresses the team has admitted they control were the only validators.

As discussed above, there is a dispute period and a dispute resolution process. The request and finalization function calls bookend that process when the administrator does not invalidate any of the requested withdrawals. The addresses initiating these calls are EOAs. So the calls are signed either manually or by an off-chain process the team has given access to their private keys, further evidencing that the operation of Hyperliquid is neither fully-automatic nor decentralized. It may be automated — but it is automated like an oven timer: a person sets it up, controls it, and can shut it down.

Note that this approval step — the team’s approval of withdrawals via an off-chain process — is clearly subject to DDOS and similar attacks and this is made easier given we know the data centers used by delegation program participants. That does not guarantee Hyperliquid uses the same data centers but those would be the place for an attacker to start looking around. As the team has experienced API access issues as discussed below we know this is a real, not just theoretical, problem.

We also get a clue as to where the data centers are located when the documentation states the system runs in “Tokyo, Japan.” Examining the provided public IP addresses suggests the system is run in either an AWS or Microsoft data center (or possibly both) in Tokyo.

July 2025 Outage

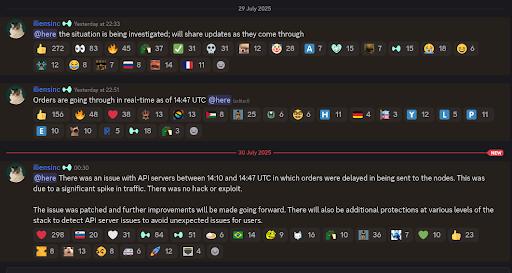

On Jul 29, 2025 Hyperliquid had an outage. Support and information, such as it was, was provided by the team on Discord. One of the founders publicly communicated in a way that makes clear they know they are the operator of the system:

Note they refer to the API servers as the root of the problem rather than the blockchain nodes. As you cannot compile and run your own code to participate in the network that is a distinction without a difference.

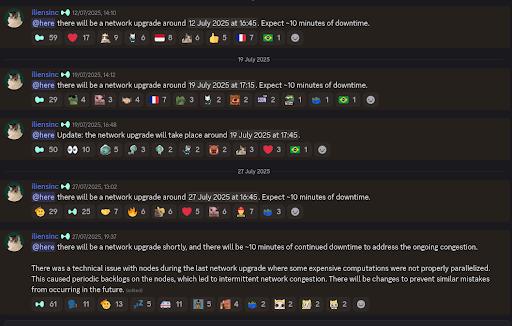

It is also worth noting that the team routinely exercises this sort of control:

Bringing the system down for 10 minutes shows the same degree of control as fixing the underlying problem causing an outage. Doubly so when the downtime serves to give the team an opportunity to fix software problems. Sometimes you might think the team genuinely does not understand the control they have. For example, plenty of DEX routers give the admin sufficient control to brick the system even if many of the developers do not appear to have figured that out yet. Hyperliquid is not like that. This team knows they have control and exercises it routinely.

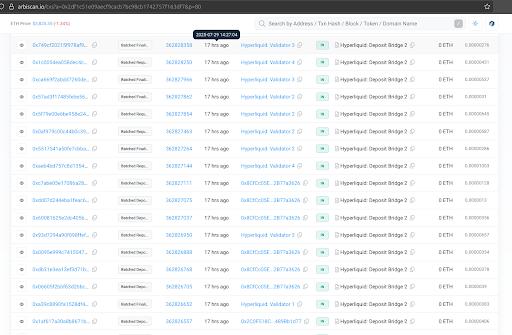

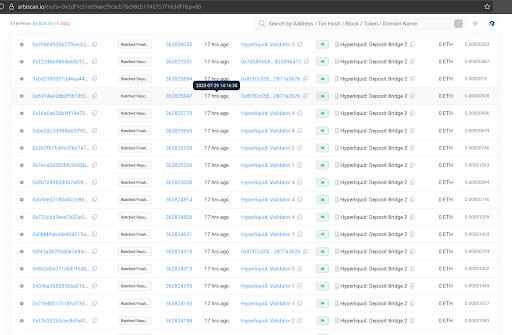

Much of the team’s off-chain infrastructure continued to run during the outage. Here we can see withdrawal approvals continuing through the API issue:

This reveals a simple way the team could use their control to exploit transactions. If the API can go down for everyone there is no reason the team could not simply take the API down for everyone else and then trade themselves. By controlling both the ability to trade and withdrawal approval the team could manipulate markets on Hyperliquid to take all posted collateral for themselves without any questionable behaviour on the Arbitrum side. As the Hyperliquid side is closed-source and non-transparent it might not even be possible for external parties to reconstruct, and prove, what happened in such an incident.

If the team arranged this “attack” to route the collateral to team-controlled addresses within the futures exchange the entire thing might just look like a large move with some dramatic ADL and then a few winners withdrawing their profits from a decentralized system. And there is nothing like a dispute mechanism here to block that.

Central Control

This establishes full central control by the team. Notice it is not necessary to update the validator set in line with the decentralization, or lack thereof, of the Hyperliquid platform blockchain. Why? Because the Hyperliquid team has the ability to proactively block withdrawals by invalidating them. Of course the team must initiate approval off-chain of all remaining “valid” requests anyway. So the closed-source side of the system need not come into the discussion to establish total independent team control either. This system operates in such a way that the team can exercise total independent control over funds on both sides of their own bridge.

Having an additional attack vector — for example, because the non-Arbitrum bits of the platform are closed-source and fully team controlled they could also steal user assets by manipulating markets — does not help the “decentralization” here.

So, to review:

- A set of only 4 team controlled addresses has approved, among them, every withdrawal request over the life of Hyperliquid.

- Only team-approved validators can effect changes to Hyperliquid or dispute pending actions.

- The team can change the validator set effectively at will, possibly with a short delay period during which nobody but the team can effect any changes.

- The team can steal all deposited user funds, currently about US$6 billion, effectively at will in quite a few ways.

Hyperliquid talks about their validator set and reports metrics for a set of validators. Other parties talk about becoming validators on Hyperliquid. There is even something that sort of looks like a Hyperliquid validator trade association. But all of those things relate to Hyperliquid’s closed-source blockchain and not the Arbitrum side which holds all the real money. Hyperliquid uses the word “validator” to mean two different things and is not careful to distinguish between them.

A cynic might say they are careful to conflate them. Next time they run this scam we recommend they at least coordinate changes on the public-visible side of the process — the validator set on Arbitrum — with changes to the private side even if there is no technical reason to do so. Such coordination will do a better job maintaining the illusion of decentralization.

As it stands, we can separate validation on the closed-source blockchain that hosts the Hyperliquid perpetual futures exchange from being in the centralized validator set for purposes of the Arbitrum smart contracts. Once you know how the system works you can pick those apart. All of this noise is at best an attempt to distract from how the system works.

The team has also acknowledged their control over other parts of the system going as far as offering refunds for losses attributable to team issues. It is not clear why the team believes these issues are particularly important if a small set of team-controlled addresses on Arbitrum exercise total independent control over the project’s 6ish billion of deposited USDC. Goodwill is, well, good. But it can also be an admission of guilt. Doubly so when that goodwill relates to an incident that lays bare yet another attack vector.

The entire system appears to be operated out of Singapore as Hyperliquid Labs is the development entity per their own documentation and that is a Singapore-registered company. This same entity signed documents on behalf of Hyperliquid that were submitted as comments to the US CFTC:

So that company looks to custody customer funds and offer leveraged trading without KYC all over the world from a single central base. Interesting.

Centralized Control In Hyperliquid was originally published in ChainArgos on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.