Author: David Wong

Source: https://www.cryptologie.net/posts/hash-based-signatures-part-i-one-time-signatures-ots/

Lamport signature

On October 18, 1979, Leslie Lamport published his invention of one-time signature .

Most signature schemes rely on one-way functions, typically hash functions, for their security proofs. The elegance of the Lamport scheme lies in the fact that its signatures depend solely on the security of these one-way functions.

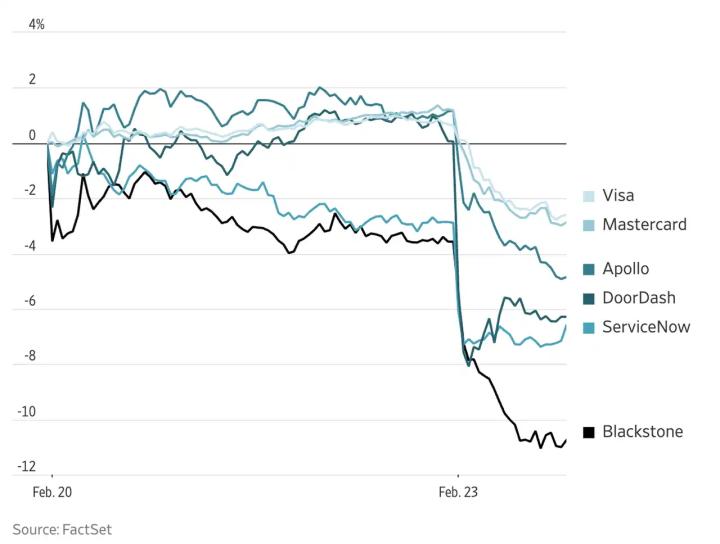

(H(x) | H(y)) <-- 你的公钥(x, y) <-- 你的私钥Lamport is a very simple scheme. First, x and y are both integers. When signing a single bit:

- If the value of this bit is

0, then releasex - If the value of this bit is

1, then publishy

Very simple, right? But obviously, you can't sign multiple times with the same public key.

So, what if you need to sign multiple bits? You can first hash the message you want to sign, for example, by putting it into the SHA-256 hash function (the length of its output is predictable, thus fixing the length of what needs to be signed).

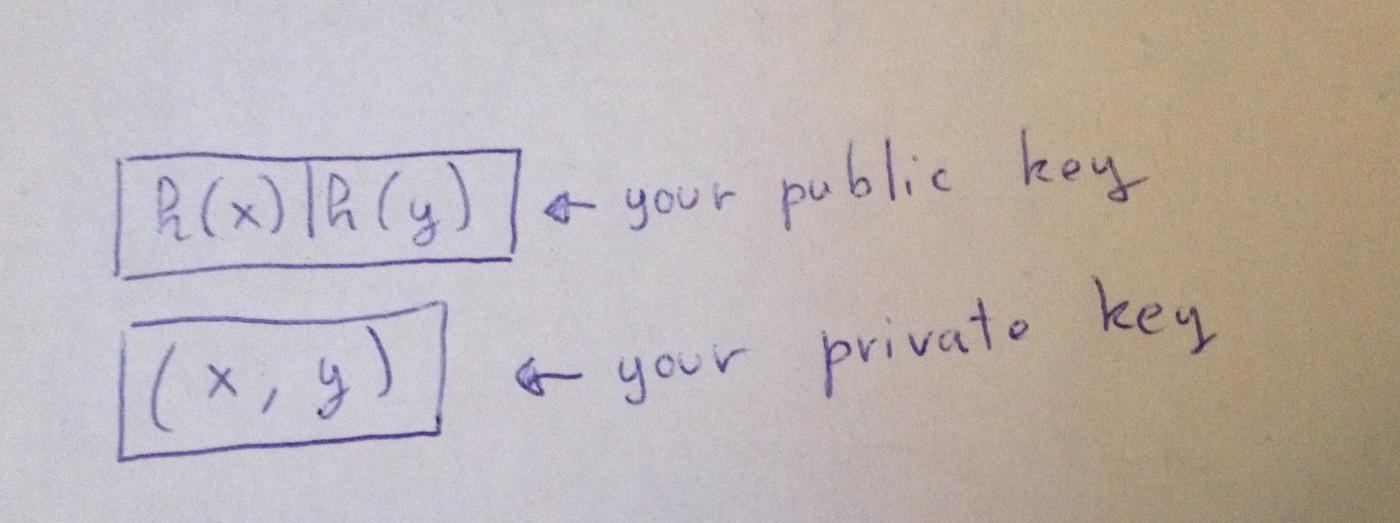

Now, (to sign 256 bits), you need 256 private key pairs:

(H(x_0) | H(y_0) | H(x_1) | H(y_1) | ... | H(x_255) | H(y_255)) <-- 你的公钥(x_0, y_0, x_1, y_1, ... x_255, y_255) <-- 你的私钥For example, if you want to sign 100110 , then you need to publish (y_0, x_1, x_2, y_3, y_4, x_5) .

Winternitz OTS (WOTS)

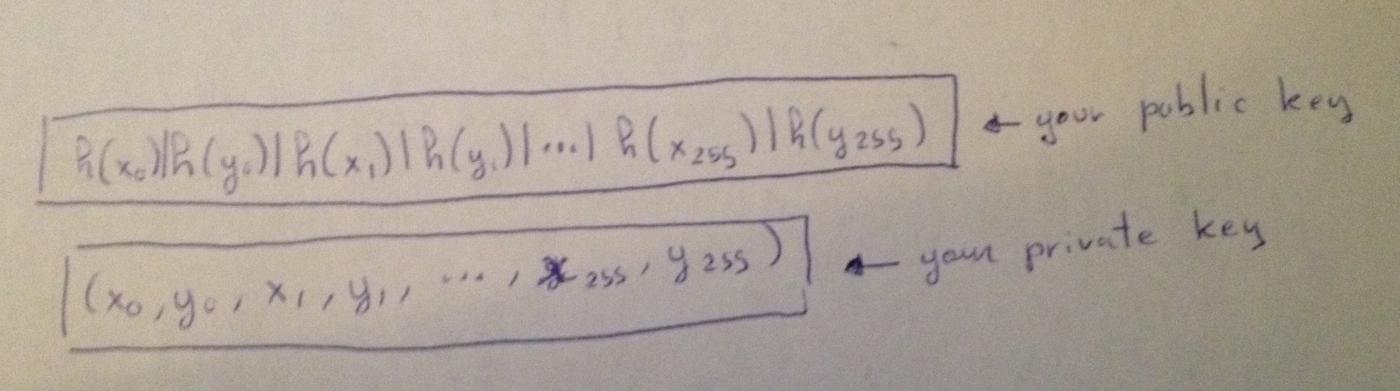

A few months after Lamport's paper was published, Robert Winternitz of the Stanford University Department of Mathematics proposed that $h^w(x)$ could be published instead of $h(x) | h(y)$.

(Translator's note: Use an integer x as the private key for one-time signing. Use H(x) to sign number 1 , use H(H(x)) to sign number 2 , and so on. Assuming the largest number you want to sign is n , then the result of hashing x n + 1 times consecutively is your public key.)

For example, you can choose $w = 16$ and publish $h^{16}(x)$ as your public key, only needing to save $x$ as your private key. Now, suppose you want to sign binary $1010$, which is $9$ in decimal, you only need to publish $h^{9}(x)$.

Now, another problem is that a malicious person can see this signature and hash it; for example, by hashing it again, they can get $h^{10}(x)$, which is to forge your valid signature for binary 1010 (or decimal 10 ).

A variant of Winternitz's one-time signature

Much later, in 2011, Buchmann et al. published an update to the Winternitz one-time signature, introducing a variant: a family of functions that take a key as an argument. You can think of this (the function) as a kind of "message authentication code (MAC)".

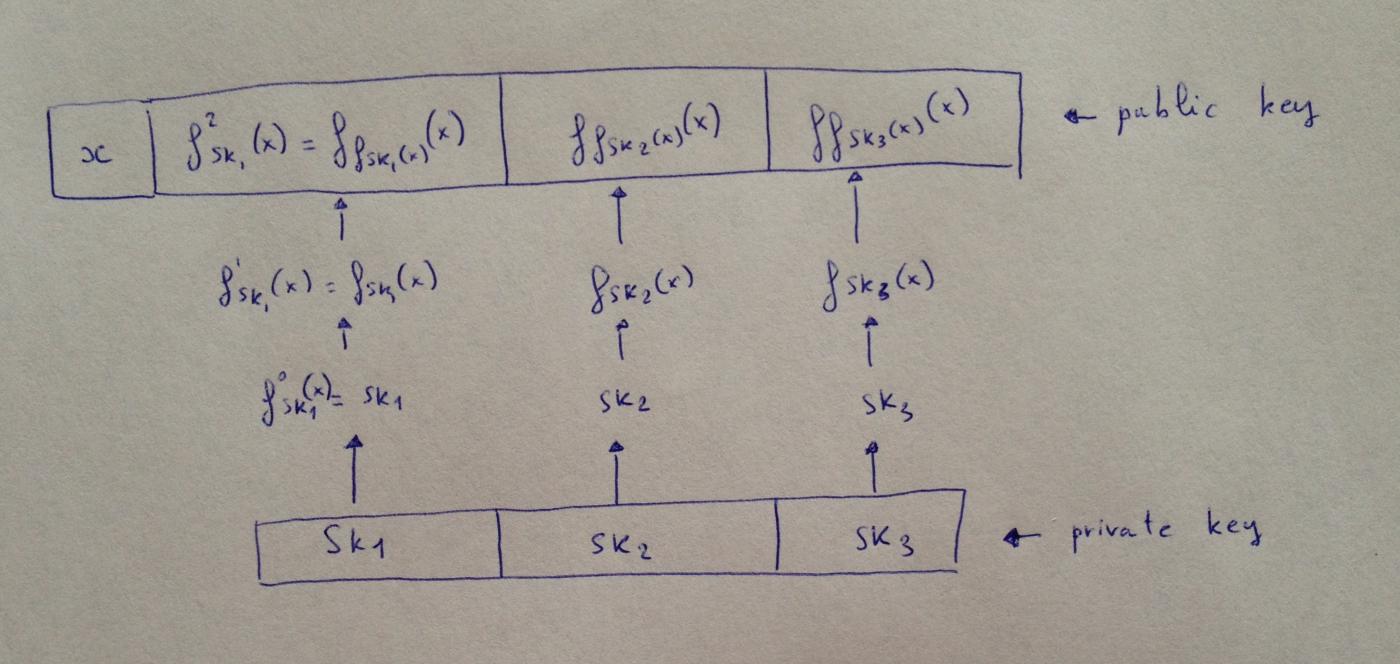

Now, your private key becomes a set of keys that will be used in the MAC, and the message will determine how many times we iterate over this MAC. This is a special kind of iteration because the output of the previous iteration replaces the key used in the function, and the input we give to the function is always the same and is public. Let's look at an example:

(Translator's note: As shown in the diagram, a key sk_i is first generated. The signature for the value 0 is sk_i itself. Then, to sign values 1 and larger, for any sk_i , the function is run once with sk_i as the parameter and x as the input; this is one iteration. The value obtained from the iteration becomes the parameter for the next iteration. x is part of the public key and is always public.)

The message we need to sign is binary 1011 , which is decimal 11 Assume our W-OTS variant works with a base of 3 (in fact, it works with any base w ). Therefore, we convert the message to ternary $M = (M_0, M_1, M_2) = (1, 0, 2)$.

To sign this message, we only need to publish $(f_{sk_1}(x), sk_2, f^2_{sk_3}(x))$, where the last item is $f^2_{sk_3}(x) = f_{f_{sk_3}(x)}(x))$.

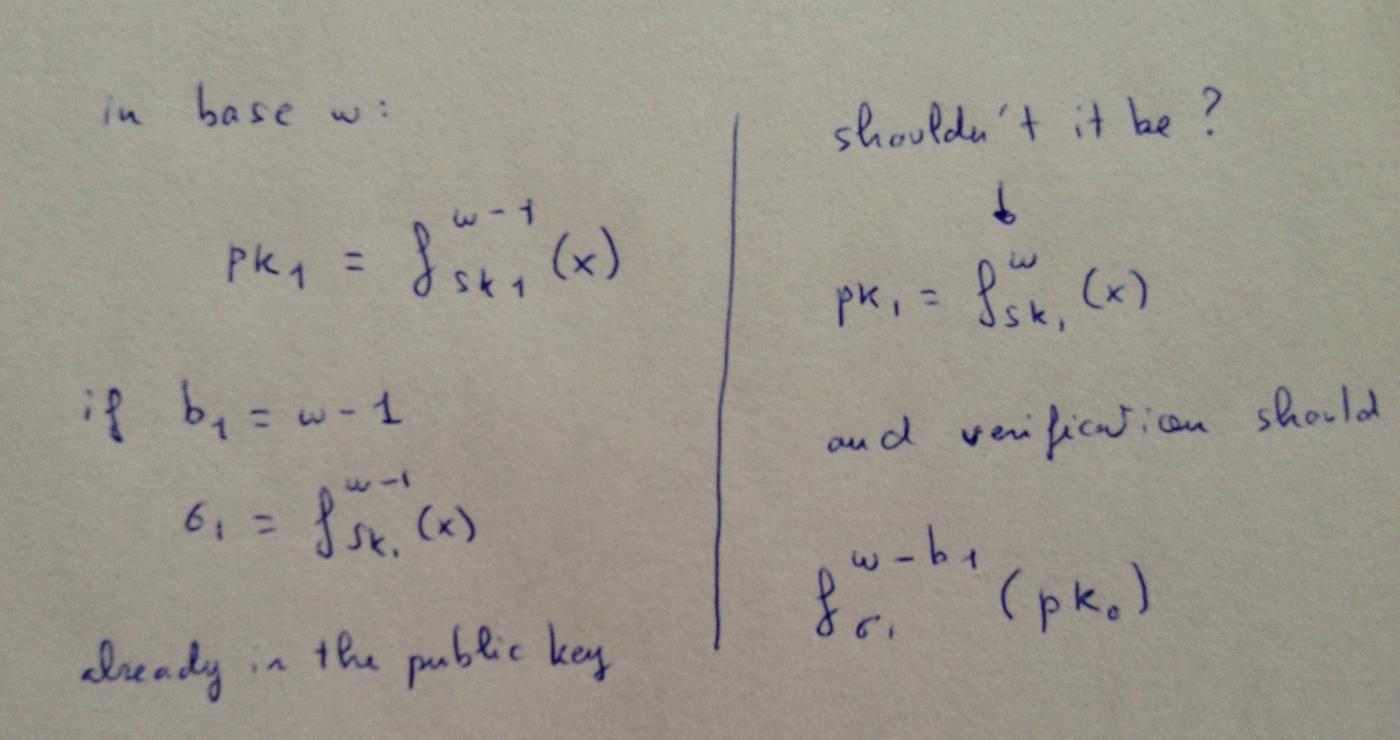

Please note that there's something I haven't mentioned here, but our message has a checksum, and this checksum also needs to be signed. This is why it doesn't matter if the signature of $(M_2 = 2)$ is already exposed in the public key.

Intuition tells us that adding a round of iterations to the public key can provide better security.

The following is Andres Hulsing's response to my question in his talk on this topic :

Why? Take bit 1 as an example: the checksum will be 0. Therefore, to sign this message, you only need to know the preimage of a public key element. For this scheme to be secure, its difficulty must increase exponentially with the security parameter. Requiring an attacker to be able to reverse the hash function on two values, or reverse it twice on the same value, only multiplies the attack complexity by 2. This does not significantly increase the security of the scheme. From a bit security perspective, you may only gain 1 more bit of security (at the cost of doubling the runtime).

(Translator's note: "Bit security" measures how many brute-force searches are needed to break a scheme. For example, "80-bit security" means you would need to run $2^{80}$ searches.)

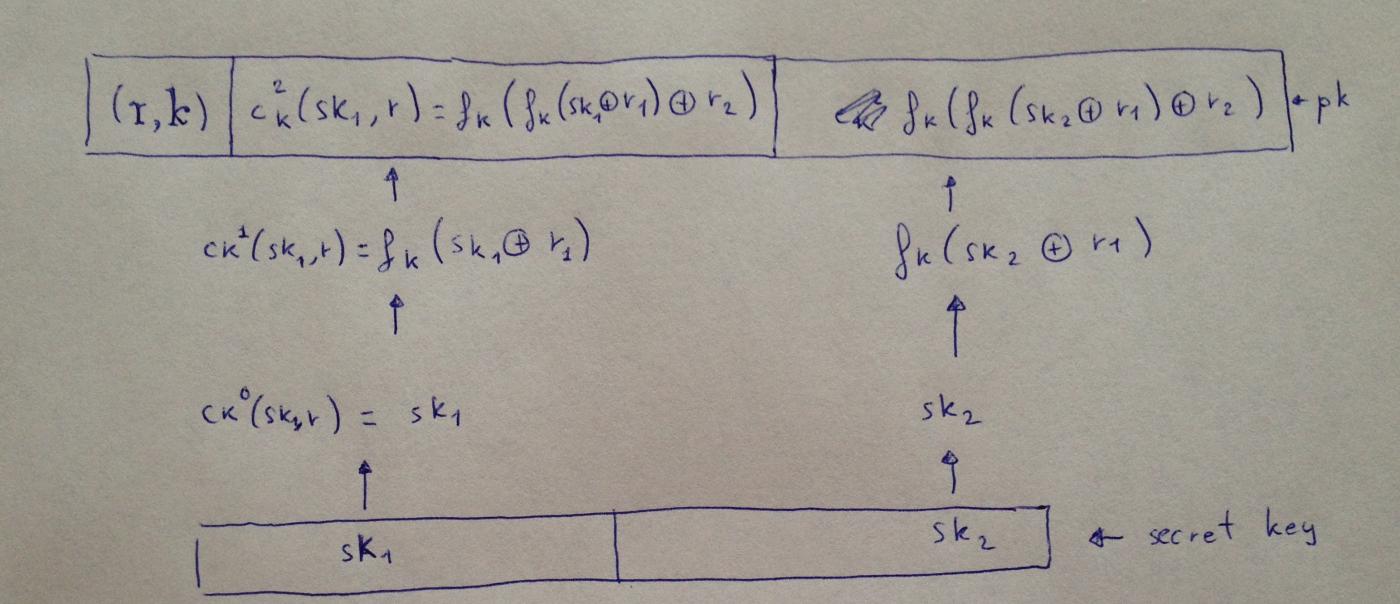

Winternitz OTS+ (WOTS+)

There's not much to say about the W-OTS+ scheme. Two years after the aforementioned variant appeared, Hulsing independently published an upgrade that shortened the signature size and improved security. In addition to the family of functions that take the key as a parameter, it also uses a chaining function. In the updated scheme, the key remains the same in each iteration; only the input becomes the output of the previous iteration. Furthermore, before applying the one-way function to this previous output, it is XORed with a random value (or "mask").

A precise description of shortened signatures from Hulsing:

WOTS+ can shorten the signature size because you can use a shorter hash function (compared to other WOTS variants with the same security level or longer hash chains). In other words, if the same hash function, the same output length, and the same Winternitz parameter

ware used for all WOTS variants, WOTS+ can achieve higher security than other variants. This is important because, for example, if you want to use a 128-bit hash function—don't forget that the original WOTS required the hash function to be collision-resistant, but our 2011 variant and WOTS+ only require a pseudo-random function/second preimage-resistant hash function—in this case, the original WOTS could only achieve 64 bits of security, which is arguably insecure. Our 2011 proposal and WOTS+ can achieve128 - f(m, w)bits of security. As for the difference between the latter two, in WOTS-2011,f(m, w)increases linearly withw; while in WOTS+f(m, w)increases linearly with w. It exhibits logarithmic growth.

Other OTS

That concludes today's blog post! However, there are many other one-time signature schemes. If you're interested, here's a list, some of which go beyond one-time signatures because they can be reused in small quantities. So, we can call them "Few-Time Signature Schemes (FTS)":

- 1994, The Bleichenbacher-Maurer OTS

- 2001, The BiBa OTS

- 2002, HORS

- 2014, HORST (HORS with Trees)

So far, the applications seem to have narrowed down to hash function-based signatures, as these are the signature schemes currently recommended for post-quantum security. See " Preliminary Recommendations for Post-Quantum Cryptography, " published a few months ago.

Also: Thanks to Andreas Hulsing for the comment.