USPD was hacked using a technique variously described as clandestine or silent. The team has claimed the hack was not visible on etherscan and that the attacker had hidden access. Those are all mischaracterizations, and maybe lies, as we will now prove. Or possibly just an overly-simplistic way to look at all of this.

A competent and non-negligent team could have, and would have, spotted trouble immediately back in September when the protocol was compromised. And any security “researcher” endorsing the view this was “hidden” is similarly incompetent, negligent and should not be trusted.

Using only publicly available free tools like etherscan it was possible for the team to tell at the time of deployment there was a problem. A competent and diligent team would have spotted this. No special tools were required. Yes etherscan suppresses some relevant information some of the time. We are on record that trusting etherscan unquestioningly to tell you what is happening is a bad idea. We are also on record that, in our view, teams hide behind etherscan’s inadequacies to misrepresent the degree of control those teams exercise over their own products. Maybe our opinion should be even lower: what if these teams do not realize they have control because it does not show on etherscan? That would be messy, dumb and sad.

But USPD is not that complicated. This was, provably, some mix of negligence and incompetence because the relevant information was not suppressed. Yes, we should expect developers to employ whatever tools are necessary to ensure their systems are deployed properly. But there is a difference between failing to use specialized software, or build your own complex surveillance tools, and what happened here. This team failed to use standard, freely-available software and then lied that the problems were not visible with such software.

Now we will prove this is a case of ignorance and error rather than some complex clandestine attack that a reasonable team might have missed. Yes, the team missed this problem. We do not dispute that. Our purpose here, rather, is to lay bare the team’s incompetence and negligence. We will do that by pointing out the flashing red lights that were visible in real time when the problem occurred that the team missed.

Details

We can see in the project’s GitHub that one of the contracts they know they deployed was the “stabilizer” at 0x1346B4d6867a382B02b19A8D131D9b96b18585f2. We can go to etherscan and see the deployment transaction using standard tools. Per etherscan that was executed at Sep-16–2025 01:01:59 PM UTC.

And then we can see 6 logs off this same 0x1346 address at Sep-16–2025 01:02:11 PM UTC, 1 block later. Logs can be viewed easily using a wide range of standard free tools. Those 6 logs are:

- A RoleGranted to a closed-source contract presumably from the attacker at: 0xc2a0aD4Bd62676692F9dcA88b750BeC98E526c42.

- Another RoleGranted to the same closed-source contract.

- InsuranceEscrowUpdated, updating the insurance escrow contract, to the same closed-source contract.

- Initialized, indicating the protocl was initialized.

- Upgraded indicating some kind of proxy upgrade to 0xAC075b9bf166e5154Cc98F62EE7b94E5345Cc090, another closed-source contract.

- Upgraded this time to the actual USPD implementation contract.

If the team had simply looked at the events on their own contract post-deployment they would have seen these events. This could be done on etherscan. Or a wide variety of other places free and non-free.

The two referenced closed-source contracts are suspicious and would have indicated to the team at once that something was wrong. Any competent team would have seen random unexpected contracts and asked what happened.

How do we know those are not the contracts the team intended? Because the addresses exposed in those events are now flagged as the attacker. We will go into a few details now but, really, once the team spotted unexpected addresses getting admin rights and proxy-linked stuff…that is about as glaring a red flag as can exist. The team did not expect those two addresses to appear anywhere so either a) they saw these logs and ignored them or b) they never saw the logs. Both possibilities are failures by the team.

The RoleGranted logs relate to permissions within the protocol and, again, it is a glaring red flag that permissions were granted to random external contracts.

And as we said above, security researchers now list those two addresses above as malicious. For an external party it was not possible to know for sure if those were part of some kind of hack. These might have been mistakes. Maybe the team deployed those contacts in error and never bothered to make the source visible because they were errors that would never seen production use. We routinely find transient upgrades to random closed-source contracts on open-source protocols. Often nobody bothers to verify these transient error deployments. Other times protocols just lie about whether they are open source. That is clearly a problem but it is a different problem.

But the USPD team would have known these were security problems. The team knew what contracts it deployed. The team knew these addresses were not under their control. For an external party it was not possible at the time to tell something was wrong. But for a competent team: yes it was 100% possible using only simple, free, standard tools. It was possible for an external party to spot oddness and ask questions. And the most amusing outcome here would have been some security researcher asking USPD at the time and being rebuffed or ignored. But alas that does not look to have happened. If you know this happened feel free to get in touch.

What The Team Did Do

We can see the team recording the 0x1346 deployment address on GitHub hours after the above events. We can see a developer spent a few hours on this and needed several commits to get everything fully updated. Funnily enough that same developer was working on tests at that time. They even committed a script on Sep 18th to “redeploy USPDToken with new implementation and permissions” so you kind of have to wonder if maybe tomw1808 knew there was a problem? We have no idea if that person was responsible for verifying the on-chain deployment but that would be a good place to start asking questions. Perhaps there is an untapped vein of comedy waiting in here somewhere.

Finally, note that both project audits pre-date the deployment so they could not have spotted anything with the deployment because the deployment had not yet occurred. And nobody seems to have audited the deployment. Or, if someone did, it was not a competent — or perhaps competently received — audit.

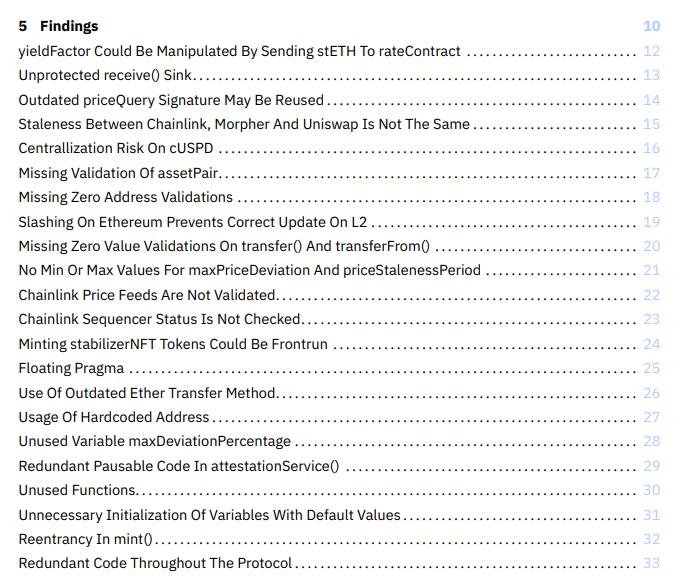

Anyway: this was not a problem with the code but rather how it was deployed. But that does not mean the code was especially good! Here is an extract from the table of contents of one audit:

You do not need to be an expert programmer to tell those round up to “this is bad, amateurish, and out-dated code.” Both audits found issues with the initialization process and both claimed, to some extent, to look at the deployment process. So yes there should be a partial black mark against the auditors for not identifying the bad deployment and initialization process more clearly. But the team surely deserves the largest measure of blame here. Again: if anyone involved in the audit process knows about more comedy here please let us know. We are open to the idea this exact problem was discussed, dismissed, and negotiated away.

Now, you can claim the deployment itself was out-of-scope if you want. But then an issue like “redundant code throughout the protocol” for a system where the code cannot be upgraded and “centralization risk on cUSPD” when that is part of the design…those are not serious problems. These audits were at-best padded out with low-value fluff. We do not know if that, too, was negotiated and maybe buried some other entertainment.

Is This A Hack?

In this case the “attacker” front-ran a portion of the deployment process and ran some of their own code to get in front of the team’s transaction to benefit themselves. Here we are using “front-ran” in a mechanical sense and do not intend to express any opinion on legality or morality.

And this sounds a lot like the Peraire-Bueno case where the supposed “hackers” took money off someone via the competitive block-building process that sits at the core of Ethereum. In the USDP case, and the Peraire-Bueno case, nobody hacked anybody’s private keys. Nobody broke into anybody’s house or office. Nobody engaged in a phishing attack or otherwise lied. Everything was within the bounds of the Ethereum protocol.

In both cases we have a form of front-running. In USDP is it vaguely like someone left the front-door open and left car keys on the table. Except transactions on Ethereum exist in an environment in which taking that car is not considered theft.

There is no daylight between using the byzantine relayer-block-builder-mempool-consensus stuff to front-run a DEX trade and front-run a deployment like this. These both “exploit” the same protocol features that the Ethereum community wanted to build and wants to use.

Coin Center’s Amicus Brief in support of the Peraire-Bueno brothers argues the front-running they did was completely fair and reasonable and legal on Ethereum writing:

Ethereum is a global technology and ecosystem. It is novel, rapidly changing, and unregulated, but for its own internal economic incentives, cryptographic controls, and the fierce competition among its validators — including Defendants and the alleged victims — as described below. Ethereum’s open source software establishes the rules and controls for that competition thanks to the voluntary software contributions of thousands of individual and brilliant developers working transparently and cooperatively. To think that the judgement of a handful of prosecutors could lead to the imposition of specific alternative technical standards for what qualifies as lawful participation in that technology and to think that those standards would manifestly contradict many of the established rules in that open source software is, in a word, radical.

So this whole thing is built around “fierce competition” within “clear” “established rules.” And anyone operating within those rules is not violating the law because all the participants voluntarily opted into this sort of arrangement. Or so the argument goes. Coin Center continues:

The alleged victims were, in fact, users of highly successful software bots that sought to engage in this ruthless competition over maximum extractable value up to the extreme limits of the protocol just as industry participants would and should expect. The alleged injury is simply that they were out-competed by Defendants who also sought multiple commercial and technical avenues to maximize their own block rewards up to the limit defined by the protocol’s narrow consensus rules for “honest” participation.

They continue to argue this is all good because simple clear rules are the only way to get optimal outcomes and, again, everyone involved chose to participate on these terms:

Amongst thinkers in the cryptocurrency space, the goal of making miners or validators compete under minimal and crystal-clear constraints with automatic penalties for non-conformity is not some inherent prejudice toward markets or greed being good in the Gordon Gecko sense. Instead, it is a recognition that self-interest will always exist and that simpler rules for competition that are not subject to unverifiable outside information or pressure (as in outside the mathematical verification of the blockchain) will better ensure that said self-interest is cabined for a simple and politically-neutral purpose: mere mathematical transaction validation.

The USPD “attack” did not violate any of Ethereum’s consensus rules. Nobody stole anything. It was merely a case of a clever industry participant that “out-competed” an admittedly deficient team. If you want to argue the team lacked the requisite competence to opt-in to Ethereum’s competitive arena then you need to explain how the admission-approval process is supposed to work. Protecting the weak and ignorant may be a noble goal. But some process needs to determine who counts as weak and ignorant and who is allowed to play at the adult table. Calling this a hack is to argue that participating in Ethereum’s consensus process should require passing a test of competence beyond merely being able to run the software. Hmm.

This leaves us in an interesting position. Much of the web3 industry shares Coin Center’s position on the Peraire-Bueno case. If that is an honestly held position those same parties must also agree this was not a hack. Further, the industry needs to recognize this team and process were sorely deficient.

Failing to acknowledge this “hack” was completely acceptable behaviour will make clear that industry positions are inconsistent except insofar as they are self-serving. We do not expect intellectual consistency from the web3 lobby and we will not be surprised when they refuse to engage on a case such as this which exposes their hypocrisy. But it is worth asking.

Finally: failing to at least socially sanction these incompetent developers will only ensure this occurs more often in the future because it relies only on features of Ethereum the community wants to use and does not want to remove. The team should have spotted the problem in real-time and fixed the deployment process before launching. If you accept the Ethereum ecosystem as it exists today USPD had a social problem not a technical one. And that means the “solution” is also social.

USPD Hack: Details & Questions was originally published in ChainArgos on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.