Author: Jing Yang (X:@unaiyang)

Proofread by: Colin Su, Grace Gui, NingNing, Owen Chen

Design: Alita Li

summary

The problem with China's real estate market is not merely a cash flow shortage, but rather a large amount of opaque, unmanageable, and unverifiable cash flow assets with unpredictable exits, deterring capital investment. This paper proposes a path of risk clearing, asset stratification, capital exit, and institutional reform, forming a dual-exit closed loop using REITs (exit assets) and equity-based exit mechanisms. Furthermore, this paper argues that if on-chain financing (RWA) is to be used for the continuation of unfinished projects and the revitalization of existing assets, the key is not simply putting properties on the blockchain, but rather creating an executable institutional framework for custody, disbursement, disclosure, auditing, allocation, and default handling. Simultaneously, global tax information exchange systems such as CRS are strengthening their ability to identify cross-border funds and digital assets; therefore, on-chain financing must integrate taxation and compliance as part of its product capabilities to truly create a replicable capital repatriation mechanism.

01. Research Background and Problem Definition

The recent large-scale model financing stories unfolding on the Hong Kong stock market actually provide a very real reference point for the real estate market shakeout: financing is never a pure mathematical problem, but rather a productization of certainty. The successive listings of Chinese large-scale model companies, represented by Zhipu and MiniMax, on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange have been met with differentiated pricing from the market's real-money investment. While all three companies talk about AI, the underlying differences lie in the founders' personalities, investor structures, and narratives: some are more academic or focused on national strategy, while others are more global or have a dollar-centric approach. However, they share the common thread of packaging uncertain R&D investments into a path that the capital market can understand (technological barriers, commercialization pace, regulatory acceptability, and exit expectations). Details such as MiniMax's IPO raising approximately $619 million and its surge on the first day (and the list of investors betting on whom) essentially emphasize one thing: capital is willing to pay for verifiable future cash flows and for clear institutional exits.

Turning this focus back to China's real estate market, the difficulty in dealing with unfinished buildings stems not merely from the assets themselves, but from the lack of a systematic chain that allows funds to enter, remain, and ultimately exit with peace of mind: ownership transparency, fund segregation, milestone payments, continuous disclosure, independent trusteeship, default handling, and exit mechanisms. For on-chain financing to become a new form of finance, its value lies not in simply putting real estate on the blockchain, but in creating a programmable, auditable, and accountable financial infrastructure: using project-level SPVs to clearly define the boundaries of rights and responsibilities; using regulatory/custodian accounts plus on-chain credentials to first collect and then allocate funds; using project milestones (acceptance/audit reports/third-party supervision) to trigger phased payments, preventing fund misappropriation; and using on-chain cash flow dashboards to transform leases, collection rates, vacancy rates, operating costs, and CapEx into continuously updated data products. In this way, the so-called return of financing is not just empty talk, but rather fills the gap in what social capital cares about most: allowing projects to move from storytelling to delivery and cash flow. Once the certainty of delivery increases, funds may shift from waiting and watching to taking over/continuing construction/mergers and acquisitions/securitization exit.

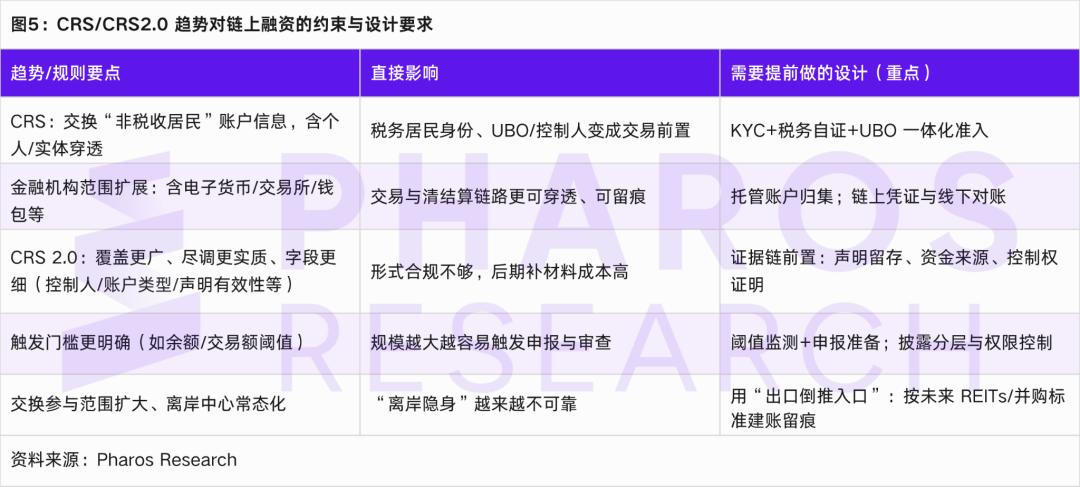

However, it's crucial to emphasize that in the era of on-chain financing, the most easily underestimated aspect is not technology, but rather the rigid constraints of taxation and information transparency, especially automatic information exchange frameworks like CRS. The logic of CRS is simple: tax authorities in various countries want to know the account information (balances, interest, dividends, etc.) of their tax residents in overseas financial institutions. It's not a question of whether it will come, but rather that it already exists and will continue to expand. More importantly, the OECD has included digital finance in its governance framework in recent updates: on the one hand, it launched CARF (a reporting and exchange framework for crypto asset service providers), and on the other hand, it promoted the revision of CRS (often referred to in the industry as CRS 2.0), including electronic currencies and CBDCs, and strengthening due diligence and data fields, aiming to close the transparency gap in the digital asset era. The OECD has also explicitly stated that the first exchanges between CARF and the revised CRS are expected to begin in 2027. Taking Hong Kong as an example, the OECD's official consultation document proposes that CARF-related legislation be completed by 2026, with service providers collecting information from 2027 onwards and exchanging information with partner jurisdictions starting in 2028; the revised CRS is planned to be implemented from 2029 (subject to the final legislation). This means that on-chain financing will not make funds more hidden, but rather will make compliance a part of financing capabilities. Especially when you are targeting overseas funds, using stablecoins for settlement, or reaching investors through financial intermediaries such as exchanges/custodians/wallets, tax residency identification, controlling person look-through, KYC/AML, and reporting data preparation under the CRS/CARF context will all become prerequisites for the transaction to be valid, rather than just back-end compliance.

The conclusion is straightforward: on-chain financing may indeed become a new channel for the refinancing of unfinished projects and existing assets, but it can not solve the illusion of where the money comes from, but rather the institutional engineering of why the money dares to come, how to prevent it from being misappropriated after it comes, and how to exit in the future; as for CRS, what you need to do is not to bypass transparency, but to make compliance a product capability in the era of transparency (qualified investor access, tax information collection, standardized custody and disclosure, auditable fund flow and allocation rules), so that on-chain financing can transform from a concept into a replicable fund return mechanism.

02. Four-stage recovery mechanism

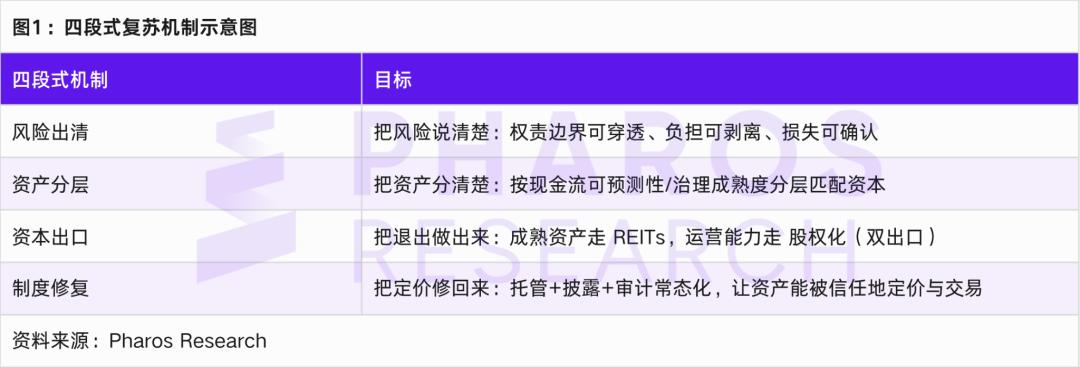

The four-stage mechanism proposed in this article does not aim for a simple slogan-like stabilization, but rather breaks down the recovery into actionable institutional actions.

The first paragraph is risk clearing. Clearing is not about getting rid of assets, but about breaking down, reorganizing, and confirming losses of risk sources such as bad debts, unfinished projects, illegal guarantees, and hidden debts through legal and financial instruments, and forming an asset package that can be traced and valued. The Pangu incident provides a highly symbolic picture: when iconic assets were packaged and put up for auction in judicial auction, the total starting price of about RMB 5.94 billion still failed to attract any bids and the auction failed. [9] This shows that in the absence of sufficiently transparent cash flow disclosure and operational certainty, landmarks cannot automatically become cash. The key to clearing is not the auction, but the asset governance before the auction: ownership penetration, burden stripping, lease authenticity, operating cost structure, cash flow collection and regulatory account arrangement.

The second part is asset stratification. Real estate assets are not a single species: residential developments, commercial office buildings, hotels, industrial parks, public rental housing, and urban renewal projects all correspond to different cash flow patterns and capital preferences. The purpose of stratification is to upgrade assets from "categorized by use" to "categorized by cash flow predictability and governance maturity," thus matching underlying assets with subsequent exit tools.

The third paragraph is about capital exit. This article emphasizes a dual-exit structure: mature cash flow assets go through REITs, while platform-based operation capabilities and urban service capabilities go through equity (Pre-IPO, mergers and acquisitions, private equity secondary share transactions, etc.). The pilot document for commercial real estate REITs makes clear requirements on product form, due diligence, and operation and management responsibilities,[1][2][3] which means that the exit tools for commercial real estate are being institutionalized; while the list of industries for infrastructure REITs has expanded the scope of assets that can be declared,[5][6] which means that the pool of securitizable assets is expanding. With the two superimposed, the constraint of the exit mechanism has changed from "whether there are products" to "whether the assets have reached the institutionalized standards for disclosure and operation". At the same time, the relevant institutional arrangements for the normalized issuance of infrastructure REITs also provide policy background support for "normalized issuance".[4]

The fourth stage is institutional repair. The core indicator of institutional repair is not a rebound in housing prices, but the restoration of asset pricing: the market can price assets based on disclosure, governance, custody, and cash flow quality, and the exit path is predictable, replicable, and regulated. This step determines whether the recovery is a one-off rebound or the start of a new cycle.

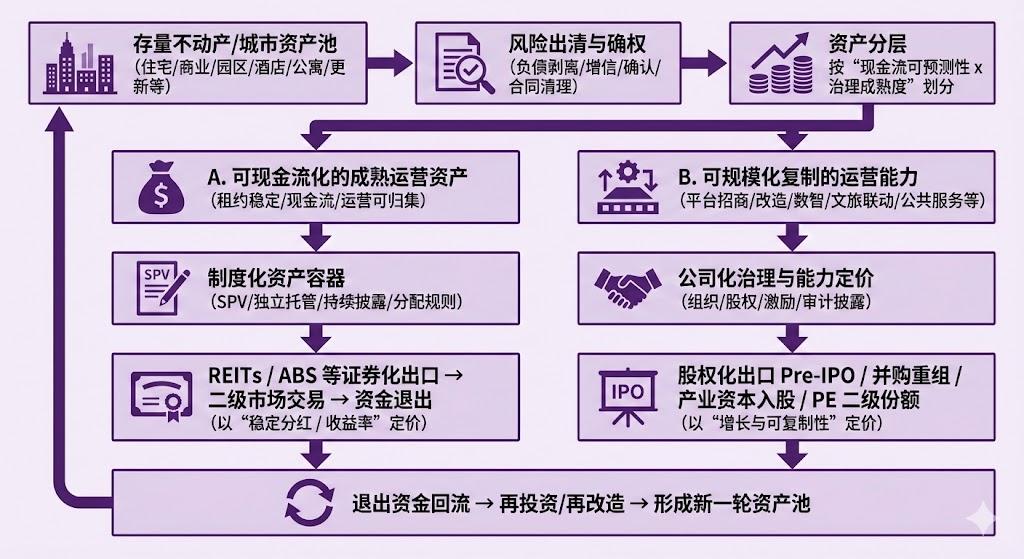

03. Dual-exit structure

In mature markets, the exit of commercial real estate does not rely on selling buildings to make a profit, but on operating cash flow and securitization exit. The practice of infrastructure public REITs in China in the past few years has trained the chain of assets, cash flow, disclosure, custody to distribution at the institutional level. [4] The launch of commercial real estate REITs has brought more typical urban operating assets such as office buildings, commercial complexes, and hotels into the field of institutional exit: the pilot document defines commercial real estate REITs as closed-end public funds that obtain stable cash flow by holding commercial real estate and distribute income to holders, and emphasizes the active operation and management responsibility of fund managers. [1][2][3] This means that the key to whether REITs can be done in the future is not whether the assets are luxurious, but whether the assets can generate stable cash flow like infrastructure and be continuously disclosed and governed.

REITs buy predictable cash flow, while equity buys replicable growth potential. When you put real estate and urban assets into this framework, many seemingly insurmountable contradictions will automatically be explained.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of the chain from assets, cash flow, disclosure, custody to distribution

Source: Pharos Research

First, REITs are inherently a system that transforms assets into income-generating products. In mature markets, the core pricing method for REITs is distribution and yield: investors are not betting on how much a building will appreciate, but rather on how much stable cash flow it will generate over the next few years and whether it can continue to distribute income. Therefore, REITs have a natural preference for underlying assets: relatively stable leases, resilient occupancy rates, collectable cash flow, explainable expense structures, and continuous disclosure. In other words, REITs essentially transform the operating cash flow of real estate into a securitizable income right, similar to infrastructure. It excels at solving the problem of how to move a building or group of buildings off-balance sheet once it's operational, allowing funds to exit, assets to continue operating, and capital to circulate. So, the real logic behind saying REITs are suitable for exiting assets with readily convertible cash flow is that the institutional requirements and investor pricing methods of REITs determine that they are better suited for taking on assets with stable operations, and not adept at taking on assets with high development risk, high uncertainty, or strong narrative-driven growth.

Secondly, the value of many urban assets lies not in the buildings themselves, but in the ability to make them operational. In reality, the real differentiator between assets like office buildings, commercial complexes, industrial parks, and hotels is often not the location itself, but operational capabilities: the ability to attract tenants determines the tenant structure, which in turn determines cash flow stability; energy efficiency upgrades and engineering management determine the cost curve; digital management determines collection rates and risk visibility; and the synergy between cultural tourism and commerce, as well as the provision of public services, determines customer traffic and space efficiency. More importantly, these capabilities can often be replicated across projects: making one building successful is one thing, but replicating the methodology, team, and system for making one successful building successful is another. The capital market naturally prices such assets more like equity: it looks not only at current profits but also at growth curves, replicability, and the scalability of the organization and system. Thus, equity-based paths (Pre-IPO, mergers and acquisitions, industrial capital investment, private equity transfers) become a more natural exit, because they allow future scalable capabilities to be bought, integrated, and valued at a premium as core assets.

Third, why not reverse the process: use REITs for exits and equity for asset exits? Because the constraints of the instruments are different. The structure of REITs makes it more like a profit distribution machine: it requires sustainable underlying cash flow, sustainable disclosure, and minimal volatility. The market also tends to price assets based on yield, which naturally reduces the weight of growth stories. If you put an operating platform company into a REIT, investors will still ask: Is your income stable rental income? Does your profit fluctuation come from expansion? Does your expansion bring development risks? Once the answers lean towards growth and expansion, the pricing framework of REITs becomes uncomfortable. Conversely, using equity to acquire a bunch of mature assets is also possible, but equity investors often want higher returns and stronger growth expectations; while the most certain value of a bunch of mature assets is precisely stable but limited-growth cash flow. These assets are more likely to obtain lower capital costs and a broader investor base through REITs (or similar securitization), and are also more in line with regulatory and information disclosure logic.

Fourth, these two exits are not separate but rather mutually reinforcing. The strongest form often involves the platform company equitting its operational capabilities (attracting industrial capital, facilitating mergers and acquisitions, and scaling up), while simultaneously injecting mature assets into REITs (forming an asset securitization exit). The platform company earns long-term returns through management fees, operational service fees, and asset recycling. In this way, REITs provide asset-level exits and capital inflows, while equity equities provide capability expansion and valuation premiums. Together, they transform urban assets from development and sales to a capital cycle of operation, securitization, and reinvestment.

04. Case 1: What does the discounted failure of a judicial auction reveal?

The significance of the Pangu incident lies not in gossip, but in the institutional signal: when a landmark asset can be auctioned off, packaged, and publicly listed, yet still frequently fails to sell after being discounted, [4] it indicates that the market does not lack assets, but rather credible assets. In the absence of a systematic information disclosure and cash flow collection mechanism, investors face a set of unanswerable questions: What is its real rent? Is the lease stable? What is the structure of property and tax costs? Are there any historical encumbrances? Is the cash flow collected into a regulated account? What is the future capital exit path?

Pangu is not an isolated case. It represents a typical example of asset pricing failure: the asset has a very strong physical form but a very weak financial form. In other words, what it lacks is not location, but institutionalized financial tradability. This also explains why a real estate recovery cannot rely solely on interest rate cuts, easing of restrictions, and sentiment restoration: if assets remain opaque, unmanageable, and unsustainably disclosed, capital will not give them a stable price.

05. Case Study 2: How to Institutionalize Real Estate as a Product of Overseas Golden Visa Programs

In contrast to Pangu, the institutionalization of overseas real estate plus identity projects is relatively low. Taking the Greek Golden Visa as an example, its policy design does not treat real estate as a speculative target, but rather as a ticket to compliance: investment thresholds are tiered by region, single property and area requirements are set, and restrictions are placed on the use (especially short-term rentals). Public legal and institutional interpretations show that the investment threshold for the Greek Golden Visa in some regions has been raised to 800,000 euros or 400,000 euros, while retaining the 250,000 euro path related to renovation/use conversion. [14][17] At the same time, short-term rental restrictions are imposed on properties obtained through the Golden Visa (e.g., Airbnb-style short-term rentals are prohibited), and descriptions of potential fines or even licensing risks for violations have appeared in the interpretations of many professional institutions. [16] Such projects are often simplified in market communication as buying a house to obtain citizenship, but from the perspective of institutional engineering, it is more like a packaged product of assets, compliance, use, and rights:

You're not just buying a house; you're buying a comprehensive institutional arrangement with clear ownership, defined thresholds, controlled use, and renewable rights. In contrast to the lack of transparency, unstable governance, and uncertain exit strategies in some domestic existing assets, overseas projects price risk in a more financialized way. The lesson for China's real estate market is that true recovery isn't about making assets expensive again, but about making assets priced in a trustworthy manner once more.

06. The Implementation of Institutional Engineering

Secondly, there's independent custody and cash flow aggregation. Whether it's REITs, ABS, or equity exits, investors ultimately buy the credibility of the cash flow. Custody arrangements must first aggregate and then distribute the cash flow, and support regulatory verification through transparency. This is where fintech excels: account systems, payment clearing, access control, risk control strategies, and audit documentation.

Third is the cash flow dashboard and continuous disclosure. The reason why Pangu-style assets are difficult to transact is essentially because the assets cannot be continuously explained. The dashboard is not a PowerPoint presentation, but a continuously updated data product that transforms leases, collection rates, vacancy rates, energy costs, maintenance capital expenditures (CapEx), taxes, and allocation rules into assets that are driven by data rather than stories.

When these three things are met, a good asset can be defined: it is not about luxurious decoration, but about predictable cash flow, sustainable disclosure, and verifiable governance.

07. RWA on-chain

In the longer-term capital cycle, RWA on-chain can become an accelerator for the dual-exit structure, but only if it is placed back into the context of institutional engineering, not marketing. BIS/CPMI describes tokenization as the digital representation of traditional assets generated and recorded on a programmable platform, emphasizing that it may reshape the entire life cycle of assets through platform-based intermediaries, but requires sound governance and risk management. [18] FSB also points out that tokenization may change the traditional market structure and the roles of participants, and attention needs to be paid to its implications for financial stability. [19] IOSCO's report further discusses the risks, market development obstacles and regulatory considerations of tokenized financial assets from the perspective of securities regulation. [21][22]

Applying these frameworks to real estate and urban assets, the correct way to approach RWA is:

(1) What is represented on the chain is not the house, but the equity and cash flow distribution rights of the SPV;

(2) What is recorded on the chain is not the price, but a verifiable certificate of cash flow and compliance status;

(3) The tokens traded on the chain are not unregulated tokens, but rather constrained shares that can be held in custody, audited and disclosed, and transferred in a controlled manner.

In terms of engineering implementation, this paper suggests adopting the path of "permissioned chain/consortium chain + regulatory readable interface": hash the key fields of ownership and contract on the chain, and keep the original materials by the custodian and the auditor; cash flow is collected in the regulated account system, and the results are mapped to the chain through verifiable reconciliation; allocation and restrictive terms (such as qualified investors, lock-up period, and usage restrictions) are made into executable rules through smart contracts. In this way, the value of the chain is not to eliminate intermediaries, but to make intermediary behavior verifiable and to move institutional credit from paper to an auditable operating system. [21]

When RWA’s goal is defined as the digitalization of institutional credibility, it naturally serves a dual-exit structure: mature assets can use blockchain to improve disclosure and liquidation efficiency within the REITs/ABS system; the equity exit of the operating platform can use blockchain to standardize the underlying assets and operating data into due diligence packages, reduce information asymmetry costs, and improve M&A and financing efficiency. [24]

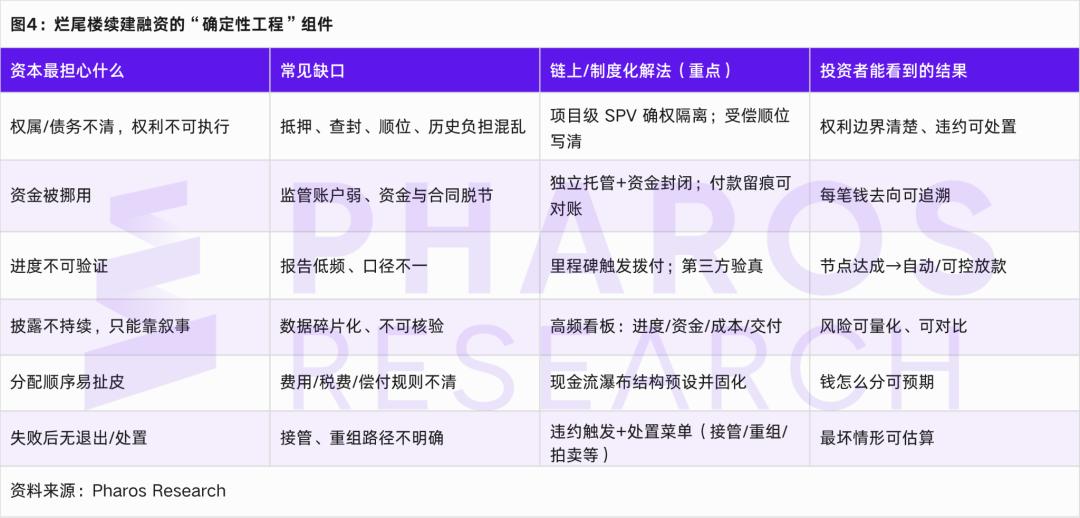

7.1 From Financing Narratives to Deterministic Engineering

In recent years, the capital market has shown significantly less patience for narratives and a marked increase in pricing for certainty. The success of large-scale corporate financing and IPO stories lies not in their grandiose visions of the future, but in their ability to break down that future into verifiable pathways: when to deliver, how to commercialize, how to disclose information, and where the exit mechanism lies. Applying this to unfinished and stalled projects, the difficulty in financing is not simply due to interest rates or sentiment, but rather the lack of an executable governance structure to answer three fundamental questions: why is the money willing to come in? How can we ensure it isn't misappropriated? And how can we handle and exit if progress falters?

In the context of real estate, on-chain financing is most easily misunderstood as putting assets on the blockchain. But a more realistic positioning is that it is a method of engineering certainty, that is, to solidify the most critical and questionable links in project governance, such as ownership boundaries, fund collection, node disbursement, continuous disclosure, allocation order and default handling, into a systematized process, and make key records auditable, traceable and accountable. [18][19] In order to avoid conceptualization, Figure 4 directly corresponds "what is the most feared thing in financing unfinished buildings" with "what should on-chain financing do".

Under the above structure, whether so-called on-chain financing can help unfinished buildings recover their financing depends not on the issuer turning the assets into Duoku tokens, but on whether the project side has truly completed deterministic production: funds are under closed management, disbursements are bound to engineering nodes, disclosures can be continuously reconciled, and allocation and disposal rules are enforceable. As long as this system can run, financing will no longer be a life-sustaining injection, but more like a replicable project financial product: the initial funds are used to continue construction to form delivery, delivery and operation form cash flow, and the cash flow is then used to complete repayment and profit distribution through a predetermined waterfall structure, ultimately creating preconditions for subsequent REITs, ABS, mergers and acquisitions or equity exits. [18][21][23]

7.2 CRS and On-Chain Financing in the Era of Tax Transparency

A very real change is that the logic of CRS has long since expanded from traditional bank account reporting to a broader scope of financial intermediary penetration. In the CRS materials you provided, the financial institutions defined by CRS not only include deposit-taking institutions, custodian institutions, investment institutions, and certain insurance companies, but also explicitly include a "newly added financial institution" category, covering electronic money providers, crypto asset investment institutions, crypto asset exchanges, and digital wallet service providers. This means that once a digital financial chain possesses financial intermediary attributes, it becomes increasingly difficult to remain outside of information exchange and penetrating identification. At the same time, the materials also emphasize that CRS 2.0, compared to 1.0, focuses on expanding coverage, strengthening due diligence, adding reporting fields and including digital assets, and in jurisdictions such as Hong Kong, more explicit reporting trigger thresholds and stronger transaction definition requirements have emerged.

Within this framework, the core argument that the CRS section wants to express in the paper should be clearer and more concrete: on-chain financing does not inherently lower transparency requirements; on the contrary, under the trend of global tax information exchange and digital financial penetration identification, it will transform compliance from back-end management into a prerequisite for transaction establishment. In other words, for on-chain financing to become an institutionalized tool for continuing unfinished projects and revitalizing existing assets, it must simultaneously provide two kinds of certainty: first, project certainty, i.e., how funds are managed in a closed loop, how they are disbursed according to nodes, how they are continuously disclosed, and how they form predictable cash flow; second, compliance certainty, i.e., clear tax identity and control chain, explainable funding path, auditable records, and controllable and exportable disclosure. Without either of these certainties, funds either won't come, or even if they do, it will be difficult to form a replicable, scalable supply.

08. Conclusion and Trend Outlook

This article argues that the key variable for real estate recovery is not a price rebound, but whether assets can be re-priced with trust. The current problem is not just tight cash flow, but also the difficulty in clarifying the ownership and burdens of a large number of existing assets, the difficulty in sealing off funds, the difficulty in verifying cash flow, the difficulty in maintaining consistent disclosure, and the difficulty in predicting exit strategies. As long as these fundamental conditions are lacking, assets are seen by capital as risk exposures rather than investable targets, and the market can only rely on sentiment and policy to form short-term transactions, making it difficult to restore stable pricing.

Based on this, this article concludes with three points. First, the essence of clearing out assets is to transform them into rules: by clarifying the boundaries of rights and responsibilities through project-level SPVs, achieving closed-loop fund collection through independent custody and supervision accounts, triggering disbursements through project milestones and creating auditable records, and supporting continuous disclosure and default handling mechanisms, funds can be invested, retained, and withdrawn. Second, recovery requires dual exits rather than a single bailout: mature cash flow assets are more suitable for exit through REITs/securitization, while operational and urban service capabilities are more suitable for exit through equity-based paths (mergers and acquisitions, pre-IPO, private placement share transfers, etc.). Separate pricing and exit of assets and capabilities are necessary to create a cycle of capital return and reinvestment. Third, the value of RWA lies not in putting real estate on the blockchain, but in making custody, disbursement, disclosure, auditing, allocation, and disposal an executable institutional system: the blockchain carries the SPV's rights and cash flow allocation rights, and records verifiable evidence of reconciliation and compliance status, thereby reducing information asymmetry and the risk of misappropriation. Meanwhile, the trend of tax information exchange such as CRS/CARF strengthens the penetrating identification of cross-border funds and digital assets, which means that compliance is no longer a back-office cost, but will become a prerequisite for the establishment of a transaction.

Looking ahead to the next few years, the industry will shift from asset-driven to governance-driven differentiation. Firstly, while the supply and scope of REITs may continue to expand, the entry barriers will increasingly focus on compliance with governance and disclosure standards. Existing assets will no longer be scarce; compliance will be. Secondly, the valuation language for commercial real estate will more quickly return to cash flow: lease quality, collection rates, vacancy rates, operating costs, and CapEx will become core pricing parameters. Thirdly, mergers and acquisitions and platform-based operations will become more important, with capital more willing to pay for replicable operating systems. Fourthly, RWA (Real Estate Management Assets) is more likely to move towards a licensing, custody, and auditing-based implementation path, prioritizing project financing loops and the refinancing of existing assets. Fifthly, cross-border funds will use tax status, controlling shareholder transparency, and auditable records as entry barriers, pushing compliance capabilities into part of financing capabilities. Overall, the institutional shift in the real estate sector ultimately depends on whether governance can be transformed into a standardized, replicable, and regulated asset operating system.