This note reviews the two equilibrium failure modes that arise in EIP-8037 when users do not wish to spend 50% of their budget on state creation, and presents the corrective state gas scaling measures that then can be deployed. In the extreme, if users continue creating as many state bytes per consumed regular gas unit as they do today and Ethereum scales the gas limit by 10x, then around 6.2% of the regular blockspace will be utilized under equilibrium. This would forfeit a great part of the scaling gains achieved via ePBS and BALs. Two direct adjustments can be made if it turns out that demand does not produce a 50/50 spending distribution: (1) adopt the EIP-8075 pricing that automatically expands and contracts the state gas limit; or (2) manually expand/contract the state gas limit, either in a regular hard fork or in a “state-gas parameter only” (SGPO) hardfork.

Failure modes

Ethereum is focused on scaling the layer 1, with headliners EIP-7732 (ePBS) and EIP-7928 (BALs) scheduled for inclusion in Glamsterdam. If the gas cost for state creation is not adjusted, state would likely grow roughly in line with an expanding gas limit. Therefore, EIP-8037 raises the gas cost for state creation substantially. A concern (1, 2, 3) associated with this change is that the proportion of the total gas that is spent on state creation may rise, thus crowding out regular gas. For example, assume that ePBS and BALs together with compute repricings allow for a 600M gas limit, a midpoint of the numbers discussed here. With the current EIP-8037 specification that relies on the EIP-8011 metering rule, if users are not sensitive to the state gas cost increase and create as much state relative to consumed regular gas as they do today, then only around 6.2% of the regular blockspace would be utilized under equilibrium. The scaling gains from ePBS, BALs and compute repricings would then largely be lost.

Of course, we may hope that users create fewer state bytes per regular gas unit when the cost of state creation increases, but the price-elasticity of demand for state creation is unknown and seems impossible to predict in a reliable manner. Should users start consuming for example half as many state bytes per regular gas unit as today, then the situation improves somewhat, and 12.3% of the block gas limit can be utilized. The ideal scenario is if users consume 8.1 times fewer state bytes per regular gas unit than today. In this case, both state gas and regular gas can be utilized at a 50/50 capacity (or realistically, perhaps closer to 40/40, if the EIP-8011 pricing uses the max operator). Should relative consumption of state creation fall more than that, then an opposite effect takes place, and users are creating less than the desired 100 GiB of state per year.

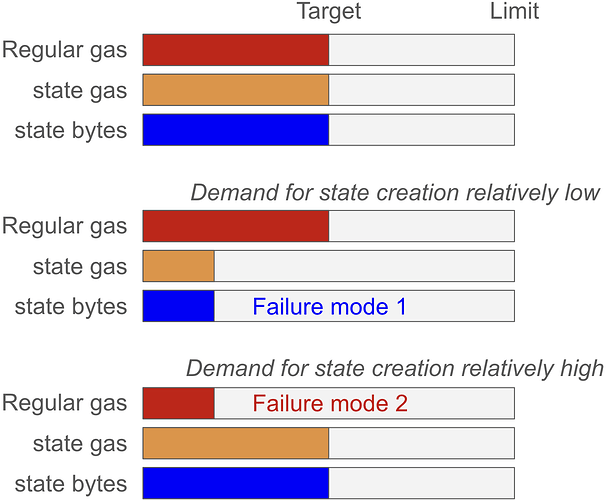

Figure 1 outlines the two equilibrium failure modes that are possible under EIP-8011 pricing: too few state bytes created, or too little regular gas consumed. The current design works optimally if users are willing to spend 50% of their budget on regular gas and 50% of their budget on state gas, regardless of the relative prices between the two. If this is not the case, one side will crowd out the other under equilibrium.

Figure 1. The two failure modes of the EIP-8011 pricing mechanism applied in EIP-8037. If demand for state creation is relatively lower than what researchers predicted, too little state is created under equilibrium (its price is too high to match demand). If demand for state creation is relatively higher than what researchers predicted, too little regular gas is consumed under equilibrium (its price is too high to match demand).

Averting failure

The deeper issue is that the EIP-8011 pricing mechanism does not track state creation over time (or more generally speaking, any value that reflects the balance in demand between state and non-state operations). It therefore cannot adjust the state gas cost such that both the state resource and regular resource are at target demand. We may end up with either state or all other resources significantly underutilized under equilibrium. There are two options to alleviate this:

- to track state creation over time using a header variable and automatically adjust the balance between state gas and regular gas, as proposed in EIP-8075; or

- to manually readjust the balance between state gas and regular gas after observing a lopsided distribution, potentially using state-gas (or state-growth) parameter only hardforks.

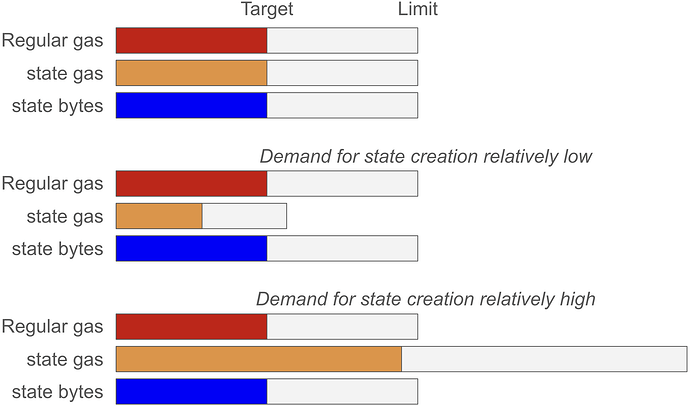

(1) Averting failure modes via EIP-8075

Applying the EIP-8075 pricing mechanism for EIP-8037 resolves the issue in a principled manner. Under EIP-8075, state creation has a variable gas cost that adapts with demand such that the desired number of state bytes are created over time. The state gas target and limit expands and contracts automatically with the gas cost (since the pricing mechanism operates over state bytes). The metered gas is computed as the average of the regular gas and a normalized measure of state gas. This allows regular gas to be consumed at its targeted level over time, while the protocol also guarantees that a target number of state bytes are created.

Figure 2. EIP-8075 automatically adjusts the gas cost with demand to ensure a target creation of state bytes in the long run. To achieve this, the EIP expands and contracts the gas target and limit while adapting the gas cost such that a target number of state bytes are consumed.

(2) Averting failure modes manually in regular/SGPO hardforks

The second option is to mirror the idea of EIP-8075, but to make the adjustments manually. The state gas target and limit can in this case ideally be allowed to expand and contract as in EIP-8075 (Figure 2), such that the metering equation remains responsive to both regular and state gas. If implemented as a SGPO hardfork, a stateSchedule can be introduced and initiated as:

{"stateSchedule": {"gloas": {"target": 107374182400,"scale": 100}},"gloasTime": "TBD"}The scale parameter allows the state gas limit to be expanded or contracted relative to the block gas limit, and the target parameter sets the yearly state growth under full utilization. The state_gas_limit is computed as state_gas_limit = gas_limit * stateSchedule.scale // 100, and the cost_per_state_byte computed by replacing gas_limit with state_gas_limit in the following expression:

cost_per_state_byte = state_gas_limit * 7200 * 365 // (stateSchedule.target * 2)When the metering function F finally is applied (where F could be max or any other function discussed here), it is just as in EIP-8075 applied to a normalized measure of state gas: F(regular_gas, state_gas * 100 // stateSchedule.scale). Since the demand-elasticity is unknown, a single manual correction may not hit the mark perfectly. It therefore seems reasonable to overshoot a little if too little regular gas is consumed under equilibrium, to retain scaling. It is also possible to “overshoot” more generally by targeting a higher proportion of state gas relative to the limit than 0.5, as outlined here.

Note that the scale parameter would be the key rationale for adding SGPO hardforks. Without the scale parameter, Ethereum risks entering Failure mode 2 in Figure 1, foregoing some proportion of the scaling gains of ePBS and BALs. The ability to also adjust the target growth is welcome, but would not in isolation warrant the implementation complexity. In other words, both the target and scale could be set and adjusted in a regular hardfork, but only the lack of a scale parameter may warrant SGPO hardforks.

Stylized equilibrium

The equilibrium outcome under EIP-8011 pricing in EIP-8037 can be rudimentarily analyzed by focusing on relative demand elasticities between the two resources (as here and here, with a general write-up on demand elasticities also available here).

There is a fixed gas cost and both resources have the same base fee. Initially, before implementing EIP-8037, 70% of all gas is spent on operations that will be charged under regular gas, G_1=0.7G1=0.7 and 30% of the gas is spent on state creation, G_2 = 0.3G2=0.3. If demand becomes balanced between regular and state gas under the fixed gas cost that EIP-8037 specifies at any given gas limit, such that users spend an equal amount of gas on both, the mechanism will work perfectly as intended. The ratio rr of the gas spent on the two resources is then 1:

Let the gas cost of state creation increase by a factor pp and let dd represent how many times fewer state bytes users are willing to create per consumed regular gas unit, under the given cost increase. The new ratio between consumed regular and state gas is then:

Under equilibrium when using the max function (as in EIP-8037) and ignoring how block variability pushes down the equilibrium proportions, the metered dimension (the larger of regular and state gas) will sit at the target. Users will then consume regular gas at a proportion of G^*_1 = \min(0.5, 0.5r)G∗1=min(0.5,0.5r) of the gas limit, and state gas at a proportion of G^*_2 = \min(0.5, 0.5/r)G∗2=min(0.5,0.5/r).

The baseline EIP-8037 cost increase at 60M gas is 1.17x for storage slots, 3.29x for accounts, and 3.67x for code. A weighted average gas cost increase across these three metrics based on current growth trajectories (storage snapshot, account snapshot, contract codes) between block 17,165,429 and block 21,000,000 is around 1.89x. Uncertainty in the current weighted average is duly acknowledged.

Investigating a 10x scaling facilitated by BALs, ePBS and repricing, the weighted average gas cost increase would with the EIP-8037 specification be 18.9x. Thus, setting p=18.9p=18.9 and assuming that users do not change their current usage pattern (d=1d=1), the ratio becomes

Users will then only consume regular gas at a proportion of

of the gas limit under equilibrium. If users halve their state creation per regular gas unit, then the equilibrium becomes G^*_1 = 0.123G∗1=0.123. The optimum reduction in state byte consumption per regular gas unit is obtained by restoring balance (r=1r=1), which implies:

Looking ahead

As Ethereum continues to scale, the difficulty in predicting the state gas cost that balances gas expenditures increases, as does the severity of the worst failure modes. As an example, at a 30x L1 scaling, only 2.1% of the blockspace for regular gas is utilized under equilibrium, if users do not change state byte creation per regular gas usage (but the high gas cost should at this point incentivize users to make rather substantial adjustments to how much state they create). By the point a 30x scaling is reached, a more comprehensive solution to the problem will ideally have been deployed. Such a solution consists of a full multidimensional fee market as in EIP-7999, and engineering efforts to better handle state growth (potentially expiring some part of the state).