Airdrops as part of a token generation event (TGE) have become very common, but relatively little studied. The mechanism is simple - distribute newly minted tokens to appropriate wallets to help establish initial circulation, enable on-chain governance, drive transactions, reward early contributors, and potentially attract new users.

We believe that such a ubiquitous element of token design deserves quantitative research to identify best practices. We collected data from over 2 million airdrop events across 40 protocols and analyzed the two most important choices facing token designers:

- How much supply of tokens should be airdropped?

- Who should be eligible to participate in my airdrop?

We use a variety of methods to answer these questions, including price performance, volatility, and wallet activity. Our analysis and dataset will be publicly available (coming soon), and we encourage contributors to help expand the dataset and analysis.

data set

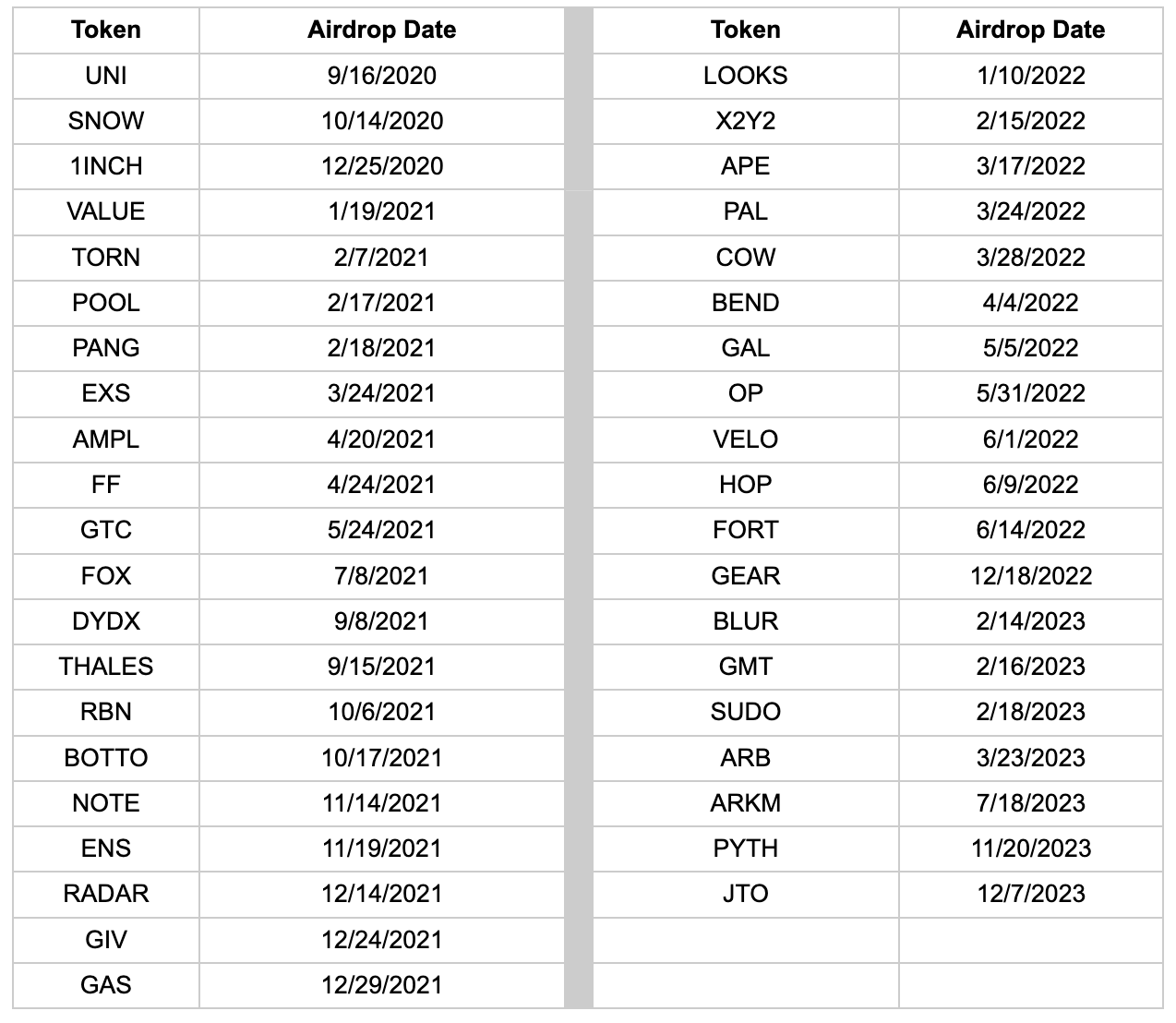

Our final dataset includes 40 airdrop events across 40 protocols, and activity from 2,098,698 unique wallets. It is important to note that we only used airdrops from 2023 and before.

Events for the following 40 tokens were analyzed:

For each of these protocols, our analysis focused on the previously mentioned metrics: eligibility type and airdrop size.

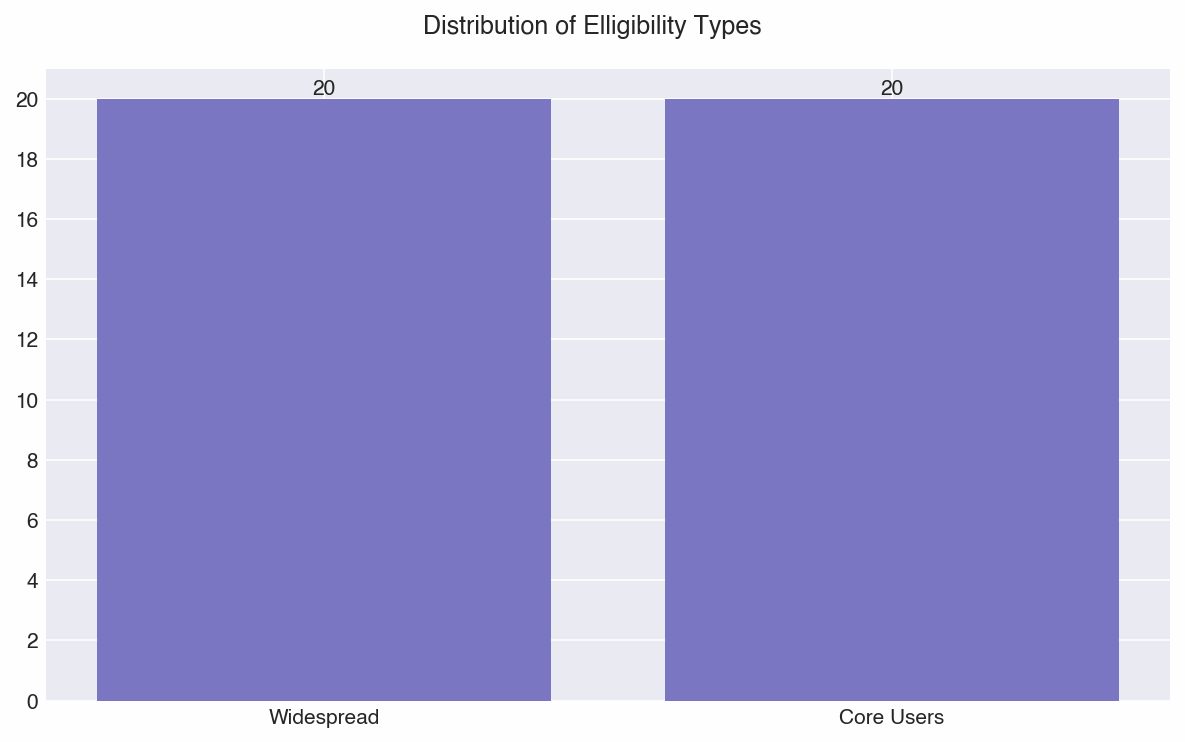

Qualification Type

“Qualification Type” is divided into “Broad Users” and “Core Users”. In the former, the protocol airdrops tokens to general ecosystem users, for example, a new DePIN protocol airdrops tokens to wallets that have participated in other DePIN protocols within a fixed period of time, or to specific on-chain communities (such as NFTs). In the latter case, the protocol only rewards users who directly participate in the pre-protocol token. Fundamentally, these approaches distinguish between two options: should airdrops be used primarily as a marketing and growth tool, or should they focus on rewarding those users who are most active during the launch of the protocol?

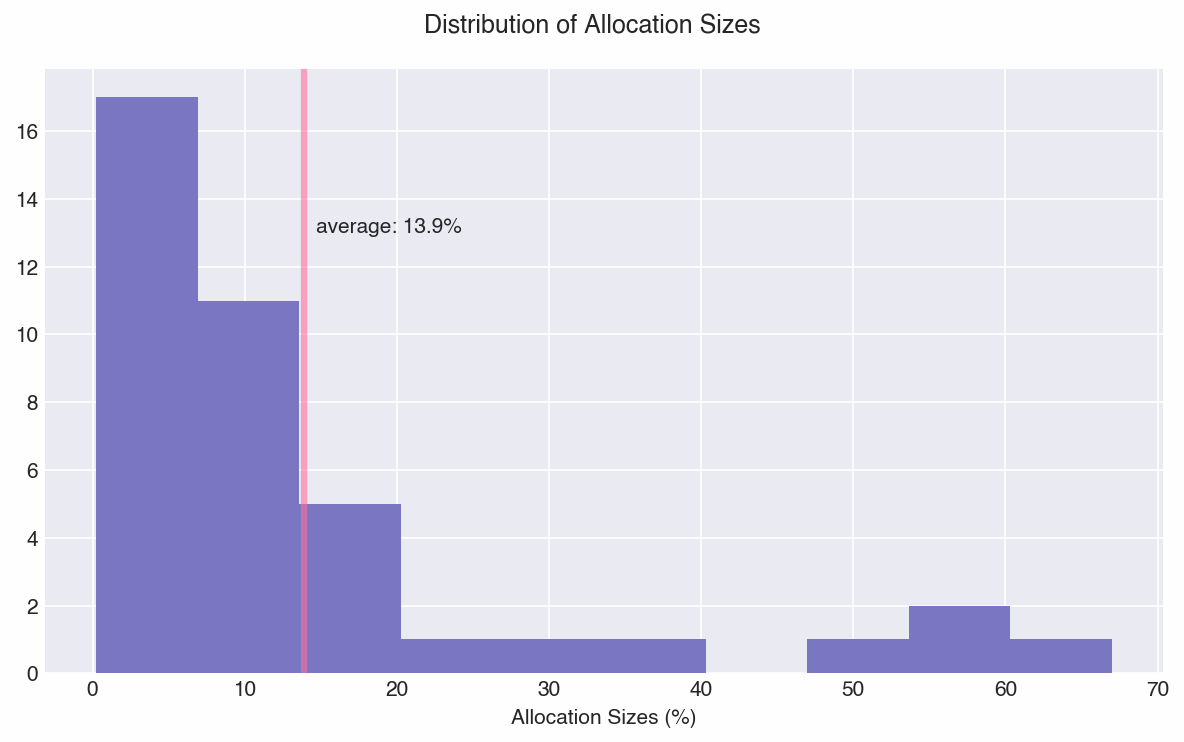

Airdrop Scale

Another key element is the “airdrop size”, which is the percentage of total supply allocated to airdrops. The motivation here is simple: is there some kind of “optimal” range of airdrop sizes? The allocation sizes in our dataset look like this:

The median allocation size was about 10%, which gives us a relatively even distribution of 19 small airdrops and 21 large airdrops.

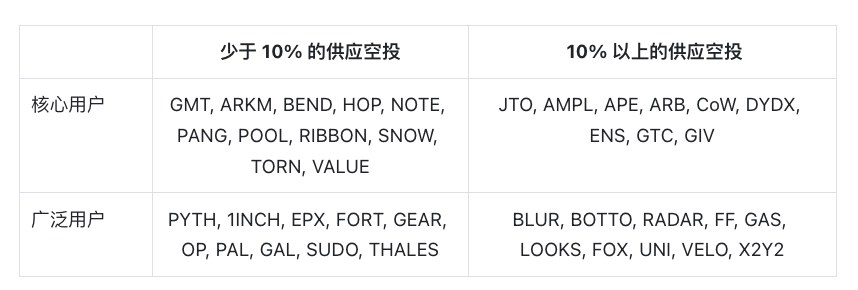

Classification

The goal of categorizing events is to compare overall design choices. To do this, we organize events into four different groups:

Analytics and insights

First, it is important to note that our analysis aims to be both rigorous and insightful - it is difficult to prove causality using only price data or wallet data, especially in a multi-factor environment like token markets. We can observe that some design combinations perform better than others, but we do not claim to rigorously prove that these design combinations perform better as a result of these design choices. We believe that a combination of factors, especially airdrops, may have contributed to the differences in average price performance between categories.

Price and volatility effects

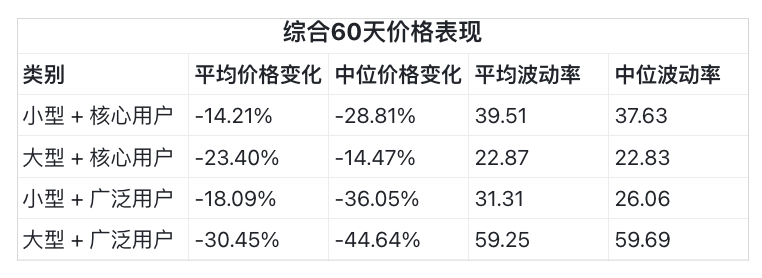

An important metric to measure the effectiveness of an airdrop is the price impact. We aim to measure the price effect within the time window that an airdrop may have an impact. Since most airdrops occur during the TGE, there are some confounding factors when analyzing price data. We collect price data for two months after the airdrop, normalize it by the crypto index (see Appendix), and calculate the percentage price change. Note that our starting price is based on 24 hours after the airdrop, thus allowing for some initial price discovery (i.e., immediate sellers).

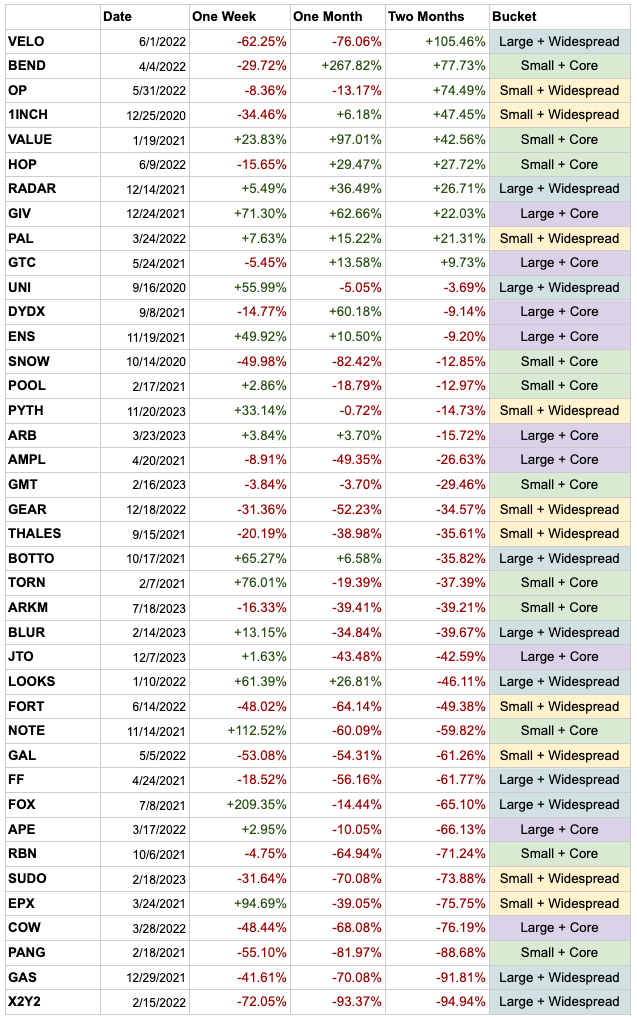

Price changes after airdrop

Only 10 of the 40 airdrops saw price increases two months after the airdrop. While we see a wide range of performance, when we measure the four categories (see chart below), they all tend to be 10-40% lower in price after 60 days. This is consistent with the large number of distribution cliffs we observed in our token unlock article. Large anticipated token distribution events (greater than 1% of token supply) typically generate selling pressure that stabilizes at lower levels after a period of time. This effect is most likely amplified in the accumulation of airdrop events.

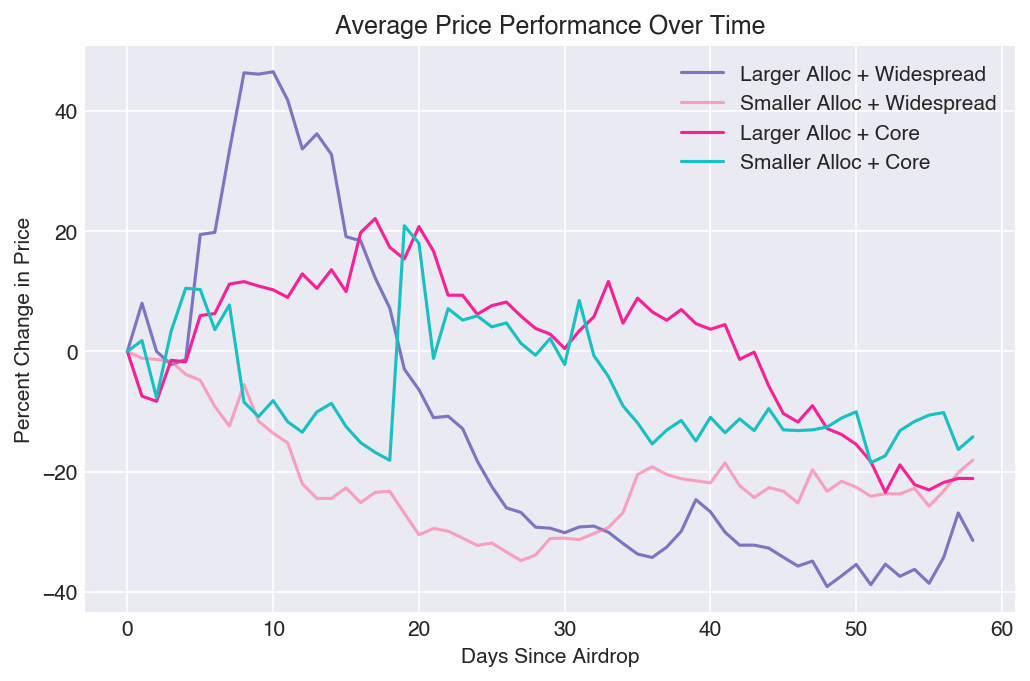

We can draw some interesting insights:

- The Large + Broad user group performed the worst in terms of price performance and volatility.

- Overall, the core user group outperformed the broad user group in terms of price performance and volatility.

- The size of the airdrop had no decisive impact on price performance or volatility.

Additionally, four protocols airdropped a large portion of their supply. Their tickers are DYDX (50%), GAS (55%), VELO (60%), and AMPL (67%). We expected a correlation between airdrop size and price, but did not observe one, neither in this group nor across all tokens (not shown). Still, the lack of correlation suggests that teams can airdrop a large portion of their tokens and still have a positive price change two months later (VELO +105%).

Wallet behavior

Another valuable heuristic for measuring the success of an airdrop is to understand what users do with the tokens they receive. For each protocol, we analyzed recipients’ wallets within 60 days of the airdrop. Note that for complexity reasons, we do not consider cases where users transfer tokens to other wallets or exchange them outside of a DEX (e.g., sending to a centralized exchange). Tracking deposits on centralized exchanges becomes infeasible at scale, and we propose to use only DEX data as a useful proxy for comparative analysis, likely as a minimum standard for sellers.

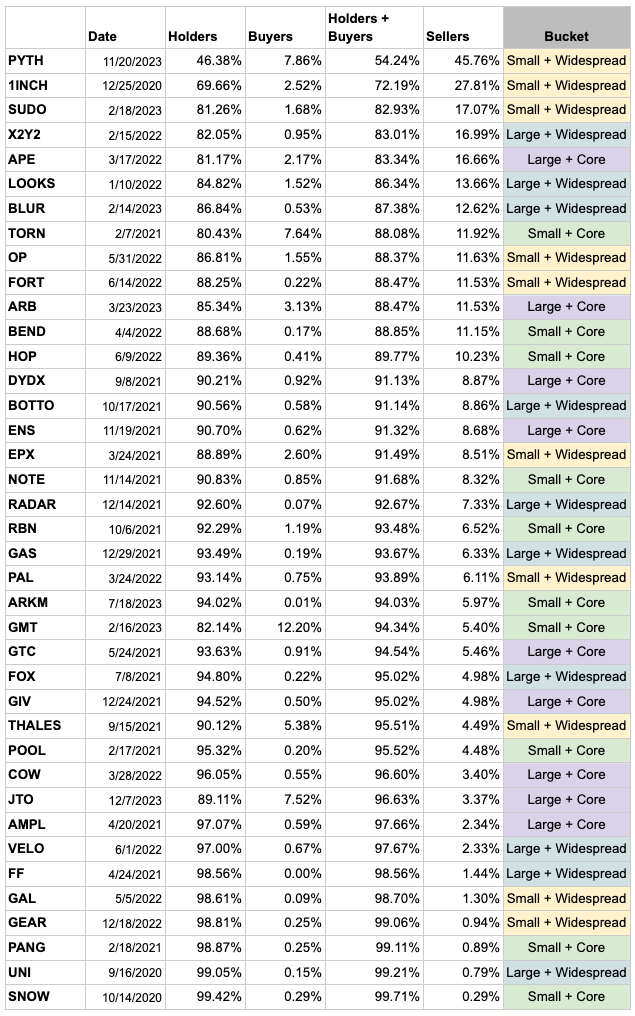

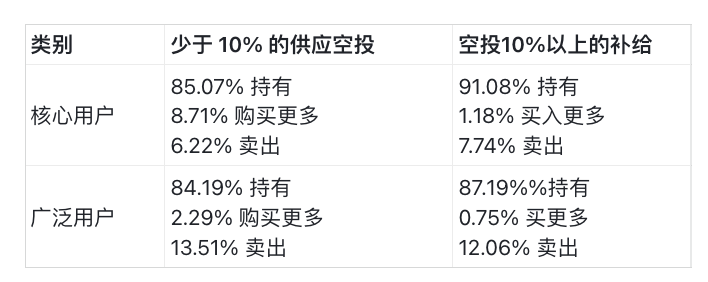

Typically, we classify users into three types: sellers, holders, and buyers. To make this classification, we calculate the net change over 60 days — users with no change are holders, users who increase their positions are buyers, and users who decrease their positions are sellers.

60-day wallet behavior airdrop analysis

We can draw two insights:

- Wide airdrops lead to two times more sellers. The average data shows that recipients of wide airdrops are more likely to sell their tokens than core users. This makes intuitive sense. If a user receives a token for something they haven’t used before, or maybe even just heard of, they are more likely to exchange it for an asset they care about. Even more telling is that 8 of the 10 protocols with the highest percentage of sellers conducted a “wide” distribution.

- Small airdrops to core users lead to a 4-8x increase in the number of buyers. The data shows that the percentage of buyers is highest when the airdrop is small (<10%) and targeted at core users. This is also intuitive, as they are the most active users and most likely to purchase tokens to participate in governance or liquidity voting.

suggestion

Our analysis revealed four key insights:

- Airdrops to core users show higher prices within two months after the airdrop.

- Airdrop size had no significant impact on price performance or volatility, which means that “low float” may not have as much of an impact on price fluctuations as other factors.

- The number of sellers in the broad airdrop group is twice that of the core group.

- The number of buyers for small airdrops + core user groups increased by 4-8 times (increased holdings).

We derive some general airdrop design biases from the data, but it is important to note that the specific context and goals of the protocol must always be taken into account.

Tip #1: Airdrop to core users rather than a broad audience

Given the opportunity cost of airdropping to users who are more likely to sell, our first general observation is that airdrops should be primarily targeted to core users who help bootstrap liquidity and/or drive usage, rather than a broader audience. Our intuition that rewarding core users will lead to higher holder retention is validated in the data. Converting non-users to users via airdrops is unlikely, and it is generally better to focus attention and funds on incentivizing the core community . Airdrops to core users are also likely to promote buying momentum and relatively higher prices.

Tip #2: Favor smaller airdrops

Given that airdrop size has no significant impact on price and volatility, we prefer to keep airdrops smaller rather than larger. Tokens help bootstrap usage and liquidity, especially if the team plans to continue iterating on its product (rather than planning to solidify it), and keeping more in reserve helps fund future rewards for attracting users and liquidity. It is important to note that airdrops should still be large enough to meaningfully reward early venture capital and serve as a motivational moment for the community.

In some cases, larger airdrops may be preferred. For example, larger airdrops can prevent voting centralization and make it more difficult for malicious actors to influence the network. However, allowing teams and investors to vote with their locked tokens may reduce this risk factor.

Observation: “Low Circulation” May Not Be the Main Driver of Price Fluctuations

Finally, as an observation rather than a suggestion, the data does not support the “low float” theory as the primary reason for large price swings. Logically, low float limits supply and should therefore drive prices higher. However, we do not observe a significant relationship between the large and small airdrop groups, with all groups experiencing lower prices 60 days after issuance. Furthermore, analyzing relative volatility does not reveal significant differences by airdrop size, even though we would expect low float to result in higher volatility. In fact, the Large + Widespread group has the highest volatility by a wide margin!

If we had unlimited resources and knowledge, we would expand our research to include evaluating the TVL of protocols before/after TGE, to assess whether airdrop size affects TVL stickiness, and to analyze the ratio between TGE price and the last major investment round.

appendix

Crypto Index Correction

To perform a balanced analysis of different macro conditions, we use beta normalization to remove macro price changes from token price changes. This is done using a multivariate regression of BTC and ETH, where we remove the beta coefficient of each asset relative to the macro and reconstruct the price after the adjustment.