Author: Neil Source: L1D Translation: Shan Ouba, Jinse Finance

This article aims to provide guidance and reference for the launch of an institutional-grade crypto hedge fund (“Crypto HF”) from an operational perspective. Our intention is to assist teams planning such launches and serve as a resource on their journey.

Cryptocurrency is still an emerging asset class, and so is the infrastructure that serves it. The goal of establishing a strong operational framework is to enable trading and investing while ensuring security and control over fund assets (both technically and legally) and proper accounting for all investors.

The information and opinions in this article are derived from L1D’s experience as one of the most active investors in crypto HFs since 2018, and our team’s long track record of investing in hedge funds during multiple financial crises prior to 2018. As an active allocator prior to the 2008 global financial crisis, and participating as an investor and liquidator in its aftermath, our team has learned many lessons and applied them to investing in crypto HFs.

As a guide and reference, this article is long and explores multiple topics in detail. The level of detail on any given topic is based on our experience with new managers and is often a lesser understood subject, often left to the purview of legal counsel, auditors, fund administrators and compliance experts. Our goal is to help newly launched managers navigate this area and work with these expert resources.

1. Planning and strategic considerations

Identifying and vetting the right partners, and establishing, testing and refining pre-launch procedures can take several months. Contrary to popular public belief, cryptocurrency investing at the institutional level is not the “Wild West” from a compliance perspective, in fact quite the opposite. Premium service providers and counterparties are very risk-averse and often have heavy and extensive onboarding processes (KYC and AML). Such planning also includes considering cuts in areas such as banking partners. As a rule of thumb, a typical fund set-up can take between 6 and 12 months to establish. It is not uncommon to launch in stages and expand into new assets, as the full scope of certain strategies may not be achievable from day one. This also means that investment managers must consider a certain expense burden when preparing for launch, as revenue will take longer to materialize.

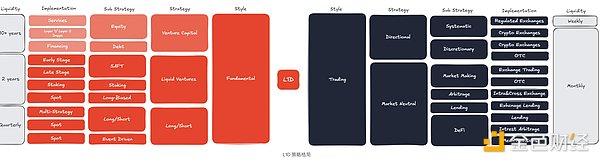

Crypto HF’s investment strategy effectively defines the fund’s operational profile and requirements, as well as the corresponding workflow to prepare for launch. The diagram below depicts what we categorize as the strategy landscape in L1D. As each strategy further defines itself through sub-strategies, implementation, and liquidity, the fund’s operational profile is also defined - as they say, form follows function. This is ultimately reflected in the structure of a particular fund, legal documents, counterparty and venue selection, policies and procedures, accounting choices, and the responsibilities of the fund manager.

2. Fund structure, terms and investors

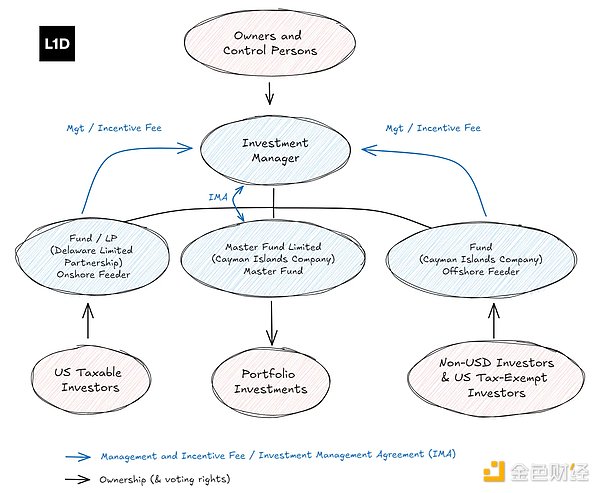

The structure of a fund is often determined by the assets traded, the tax benefits to the investment manager, and the location of potential investors. Most institutional funds choose structures that allow them to face offshore exchanges and counterparties and attract both U.S. and non-U.S. investors. The following section details the fund's offering documents and provides further detail on several key items. Included are several case studies that highlight how certain choices in the structure and language of the offering documents can lead to potential negative outcomes for investors and outright failure.

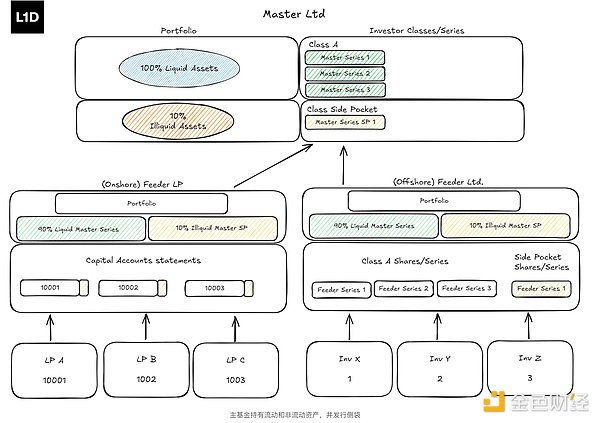

The following diagram represents a typical Cayman Islands based Master-Feeder structure.

Investor Types and Considerations

When setting up a fund, investment managers should consider the characteristics of potential investors in the following aspects to address legal, tax and regulatory implications while taking into account commercial considerations:

Investor’s Residence – U.S. vs. Non-U.S.

Institutional Investors, Qualified Investors vs. Non-Qualified Investors, Qualified Purchasers

Number of investors and minimum subscription amount

ERISA (US Pension Plans)

Transparency and reporting requirements

Strategy carrying capacity

Prospectus

The following factors are key when considering fund structure and are typically included in the fund's prospectus - such as the Private Placement Memorandum and/or Limited Partnership Agreement.

Place of Registration

Institutional funds usually choose the Cayman Islands as their primary domicile, followed by the British Virgin Islands (BVI). These domiciles provide convenience for fund vehicles to conduct business with offshore counterparties.

The Cayman Islands’ status as a preferred jurisdiction stems from the establishment of traditional financial hedge funds, around which a whole set of service providers have been built, including legal, compliance, fund management and audit, which have a good track record in the field of alternative asset management. This trend has also continued to the crypto industry as many of the service providers of the same name have established a foothold in the crypto field. Compared with other jurisdictions, the Cayman Islands is still regarded as the "best choice", and its regulator, the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA), has strengthened supervision and supervision, which is a testament to this status.

These established jurisdictions offer a high level of regulatory clarity and legal precedent in fund management, while having highly developed anti-money laundering (AML) and customer due diligence (KYC) requirements that are essential for the smooth functioning of the market. These regions are often associated with higher costs.

The higher set-up costs and lengthy legal procedures in the Cayman Islands have led many managers to consider the British Virgin Islands. As more high-quality, reputable service providers offer services in the British Virgin Islands, it is becoming an accepted jurisdiction, approaching the standards of the Cayman Islands more and more. The premium paid for choosing a well-known domicile is usually justified over the life of the fund.

Fund entities – master funds and sub-funds

A master fund and sub-funds are usually set up according to a structural diagram, where the master fund holds the investments, is responsible for conducting and executing all portfolio activities, and distributes financial returns to the underlying sub-funds.

The parent fund is usually a Cayman limited company (LTD) and issues shares.

Sub-funds for offshore investors are usually Cayman limited companies that issue shares, while sub-funds for U.S. domestic investors are usually Delaware limited partnerships (LPs) that issue limited partnership interests. Sub-funds in the U.S. can also be Delaware limited liability companies (LLCs), but this is less common.

Fund entity form - Limited company vs Limited partnership

Offshore funds and master-sub-fund structures allow for targeting of diverse sources of capital, including U.S. tax-exempt investors and non-U.S. investors.

The choice of whether to structure as a limited company (LTD) or a limited partnership (LP) will usually depend on the fund manager’s tax considerations and how they wish to be remunerated from performance fees, which usually apply at the fund of funds level.

Cayman Limited Company (LTD):

An LTD is a separate legal entity from its owners (shareholders). The liability of shareholders is usually limited to the amount they invested in the company.

LTDs typically have a simpler management structure. They are managed by directors appointed by the shareholders, and day-to-day operations are usually overseen by officers (usually investment managers).

Shares in a LTD are transferable, which provides flexibility for changes in ownership.

LTDs can issue different classes of shares with different rights and preferences, which is very beneficial for structuring investment vehicles or accommodating different types of investors.

From a U.S. tax perspective, LTDs generally elect to be treated as corporations and therefore be taxed at the LTD level rather than passing the tax liability on to investors.

Cayman Limited Partnership (LP):

In a limited partnership, there are two types of partners - general partners and limited partners. General partners manage the partnership and are personally liable for its debts. Limited partners, on the other hand, have limited liability and do not participate in day-to-day management.

LPs are managed by general partners (GPs), who bear unlimited personal liability, while LPs (limited partners) enjoy personal liability protection.

Cayman does not impose tax on foreign limited partnerships.

LPs are structured differently, with limited partners typically only providing capital but with less flexibility in share classes than LTDs.

Delaware Limited Partnership (LP):

The choice of implementing a Delaware LP versus a Cayman LP usually involves the tax and governance preferences of the investor. Domestic funds most commonly use a Delaware LP.

Delaware LP laws define governance and investor rights.

LPs are tax “pass-through” entities and investors pay their own taxes.

Delaware LPs offer flexibility in defining the relationships between the parties through the fund’s governance documents.

A Delaware LP is generally cheaper and quicker to form than a Cayman LP.

Investment Manager/Advisor/Sub-Advisor/General Partner (GP)

The entity responsible for portfolio management and is compensated through management fees and incentive fees.

The entity that has management rights and receives the fees generally depends on the ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs), their nationality and tax preferences.

A GP is usually formed as a limited liability company (LLC) to enjoy limited liability protection since the GP has unlimited liability.

Asset holding structure

Investments are typically held in a fund of funds, but other entities may be established for certain assets/holdings for tax, legal and regulatory considerations.

In certain special circumstances, investments may be held directly by a sub-fund for the same reasons as above and such arrangements must be clearly set out in the fund’s legal documents.

Share Class

Funds may offer different share classes with different liquidity, fee structures and the ability to attract specific types of investors; founder share classes are often offered to investors who invest a large amount of money early on. This class of shares may provide certain preferential terms to early investors to support the development of the fund in its early stages.

Special categories can also be created for special situations (such as assets with limited liquidity), often called "side pockets".

Different classes of shares may have different rights, but the assets in each share class are not legally distinct or segregated from the assets in other share classes.

cost

The market standard for charging management fees is to be equal to the liquidity of the fund - for example, if the fund provides monthly liquidity, then the management fee should be charged monthly (deferred). This approach is also the most efficient way to operate. As described below, it is common practice to set a lock-in period during which the management fee is charged.

Performance fees are usually accrued over a particular year and are settled and paid annually only based on the corresponding High Water Mark (HWM). Performance fees are also usually settled and charged if an investor redeems during a performance fee period above the HWM.

Some funds may prefer to crystallize on a quarterly basis and charge a performance fee – this is not considered best practice, nor a market standard, is not favored by investors, and is less common.

The side pocket assets will not receive a performance fee until they are liquidated and transferred back into the liquid portfolio as liquid assets or cash from the side pocket after liquidation.

Liquidity

Redemption terms and conditions – should be consistent with the liquidity of the underlying assets.

The lock-up period - which is determined at the discretion of the investment manager - is usually determined by the strategy and underlying liquidity. Lock-up periods can vary, 12 months is common but can be longer. The lock-up period may apply to each investor's first subscription or to each subscription - both the first and subsequent subscriptions. Different classes may have different lock-ups, i.e. the founder class may have a different lock-up period than other share classes.

Side Pockets — See below.

Thresholds – Funds can implement thresholds at the fund or investor level – Thresholds mean that if more than a certain percentage of fund or investor assets (e.g. 20%) are requested for redemption during any redemption window, the fund can limit the total amount of redemptions that are acceptable – this is done to protect (remaining investors) from the impact that large redemptions would have on price or portfolio construction.

Thresholds are often associated with illiquid assets, and the impact of large redemptions could affect the actual price of assets as they are sold/liquidated to raise redemption cash, and this feature does protect investors.

Whether to implement the threshold at the investor level or the fund level depends on the liquidity structure and the concentration of assets under management of the investor group. However, implementing the threshold only at the fund level is more common, investor-friendly, and more operationally efficient.

It is also important that threshold terms clearly state that investors who redeem before the threshold is implemented should not have their redemption rights prioritized over redemptions after the threshold is implemented - this ensures that later redemptions are treated the same as earlier redemptions and eliminates the incentive or possibility for large investors to game the system and obtain unexpected preferential treatment in liquidity.

expenditure

The fund may charge certain operating expenses to the fund, which are actually paid by investors.

Best practice is to charge to the fund those expenses that are directly related to fund management and operations and that do not cause a conflict between the fund and the investment manager, keeping in mind that the manager receives management fees for its services, and that operating and other expenses related to the management company and entity should not be charged to the fund. Direct fund expenses are typically related to servicing investors on behalf of the fund and maintaining the fund structure - administrator, audit, legal, regulatory. Management company expenses include office, personnel, software, research, technology and expenses required to operate the investment management business.

Managers should be aware of the total expense ratio (TER). Newly launched cryptocurrency funds will often have relatively low AUM for a period of time. Institutional allocators of cryptocurrency may be taking on new risks of investing in the asset class, which should not be exacerbated by high total expense ratios (TER).

In order to keep TER at a reasonable level, strengthen accountability and align managers with investors, it is recommended that managers commit to covering certain start-up and ongoing operating expenses, which is also a sign of confidence. This demonstrates a long-term commitment to the space, and the expectation of AuM growth brought about by such a commitment will compensate managers for such investment and discipline.

Good expense management can also further align the relationship between managers and investors by mitigating potential conflicts of interest. There can be a grey area between what directly benefits the fund and what benefits the manager more than the fund – attendance at conferences and events and the associated expense policy is one such area. The costs associated with maintaining such a presence are not direct fund expenses and are often more likely to be included in the management fee or even paid out of pocket by the manager.

Cryptocurrency is already a conflict-ridden industry and a true fiduciary fee policy approach is critical to establishing cryptocurrencies that are investable by institutional allocators.

Accounting

To properly track the high water mark of performance fee calculations for investors, two accounting methods can be applied - series accounting or balanced accounting.

Series or multi-series accounting ("series") is a procedure used by fund managers whereby a fund issues multiple series of shares for its fund - each series starting at the same NAV, usually $100 or $1,000 per share. A fund that trades monthly will issue a new series of shares for all subscriptions received each month. Thus, the fund will have share classes called Fund I - January 2012 Series, Fund I - February 2012 Series, or sometimes called Series A, B, C, etc. This makes it very simple to keep track of high watermarks and calculate performance fees. Each series has its own NAV, and depending on where the series sits relative to the investor's year-end HWM, those series that are above the HWM are "rolled up" into major classes and series at YE, while those that are below the HWM are aggregated because they are "below the watermark." This process is labor intensive at year end, but once completed, it is fundamentally easier to understand and manage later on.

In balanced accounting, all shares of a fund have equal NAV. When new shares are issued/subscribed, they are subscribed at the total NAV and investors receive a balanced credit or debit depending on whether the NAV is above or below the HWM. Investors who subscribe below the HWM receive a statement showing their number of shares and an EQ debit (for future incentive fees for performance between their entry NAV and HWM), and if they subscribe above the HWM, investors receive an EQ credit to compensate for any overcharges they may have received for incentive fees for purchases between the NAV and HWM. Balanced accounting is considered to be quite complex and places an additional burden on fund managers, many of whom are not equipped to do it. The same is true for the fund manager's operational and accounting staff.

Neither method is superior, as investors are treated the same in both cases, but series accounting is often preferred because it is more straightforward and easier to understand, (the disadvantage is that it creates many series that do not always aggregate in a master series, so there may be many different series over time, which increases the administrator's operational and reporting work).

FIFO — Redemptions are usually made on a first-in, first-out (FIFO) basis, meaning that when an investor redeems, the shares redeemed belong to the oldest series they subscribed for. This is a better option for the manager because if these (older) shares are above their high watermark, such redemptions will trigger the crystallization of the performance fee.

In some cases, managers will choose to apply leverage to strategies through accounting mechanisms rather than separate fund vehicles – this is undesirable and the reasons for not doing so are described in more detail in the case studies below.

In cryptocurrency investing, some investments (usually early-stage protocol investments) may not be liquid. Such investments are usually not part of the regular portfolio and are classified as side pockets and cannot be redeemed with liquid assets during the normal redemption interval.

Side pockets became popular during the 2008 financial crisis/global financial crisis - side pockets were originally a provision that allowed funds with liquid strategies to invest in less liquid assets, usually limited by a percentage of AUM, with certain clear liquidity catalysts, such as an IPO. However, due to the global financial crisis, much of the liquid portfolio became illiquid and was placed in the side pockets, and these funds experienced large redemptions, which meant that all liquid assets needed to be liquidated. The side pocket mechanism ultimately protected investors from selling assets at distressed prices, but investors in liquid funds ended up holding far more illiquid assets than intended. The intent of the side pockets did not anticipate these compounding effects of the crisis, and therefore the treatment of side pockets and their impact on investors (including valuation and fee basis) was not well thought out.

Side pockets themselves are a useful tool in the cryptocurrency space, but implementing side pockets requires careful consideration. Side pocket investments have the following characteristics:

They should only be created if there is a genuine need to protect investors.

Ideally it should be limited to a certain percentage of the fund's management size.

Not redeemable during normal redemption intervals.

are (should be) held as their own legal share class, rather than being separated simply through accounting mechanisms.

Management fees are payable but no performance fees are payable – when holdings become liquid and are transferred back into the liquid portfolio, a performance fee becomes payable.

Not all fund investors will be exposed to side pockets – generally, an investor will receive a side pocket investment if they are an investor in the fund at the time the side pocket investment is made, and investors who enter the fund after any particular side pocket investment is made will not be exposed to the existing side pocket.

When designing the side pocket structure, it is important to consider:

Offering documents - The information that the use of side pocket funds is permitted and intended should be clearly communicated; if the fund adopts a master-slave structure, both sets of offering documents should reflect the treatment of side pocket funds.

Separate share classes – Side pocket assets should be placed in their own class with corresponding terms – e.g., no management fee, no performance fee, no redemption rights.

Accounting structures within the fund structure - Side pockets are typically created when illiquid investments are made and/or existing investments become illiquid; only investors who were invested in the fund at the time the side pocket was created should be exposed to the side pocket, and such investors typically subscribe to that side pocket class. When assets in the side pocket become liquid, they are typically redeemed from their class and placed into the liquid share class, and investors who own that exposure will then subscribe to the newly created liquid class - this ensures accurate tracking of investors' exposure and high watermarks. If the fund adopts a master-feeder structure, side pockets at the feeder level should have corresponding side pockets at the master level to ensure there is no potential liquidity mismatch between the feeder and master.

The following matters are not directly addressed in the fund's offering documents, but policies must be in place to ensure alignment of interests and clear communication with investors:

Moving from side pockets to liquid assets - There should be a clear policy to determine whether an asset is liquid enough to be moved from side pockets to liquid assets. This policy and rules are usually based on some measure of exchange liquidity, trading volume, and the fund's ownership of outstanding liquidity.

Valuation – When side pocket assets are established, they are typically valued at cost as a basis for charging management fees. Side pocket assets may be valued at a markup, but must adhere to clear, practical valuation guidelines. One approach involves applying a discount for lack of market value (“DLOM”) based on recent large transactions in the asset (e.g., a recent capital raise at a valuation above the fund’s original cost).

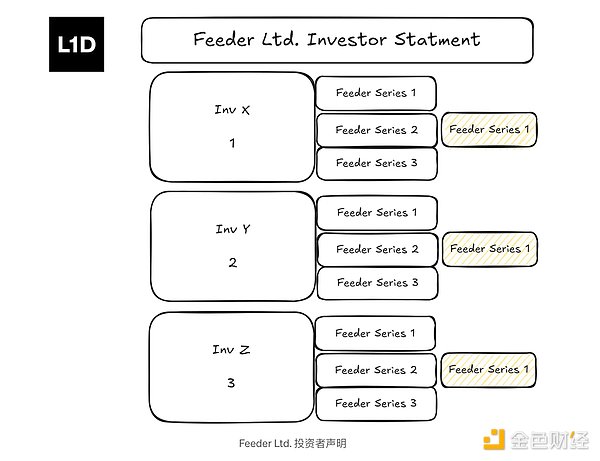

Reflection on investor presentation – Investors should have a clear understanding of their liquidity in the fund and therefore the side pocket categories should be reported separately from the liquidity categories (and each liquidity category should also be reported separately) to ensure that investors understand the number of shares and NAV per share they have which can be redeemed under standard liquidity terms.

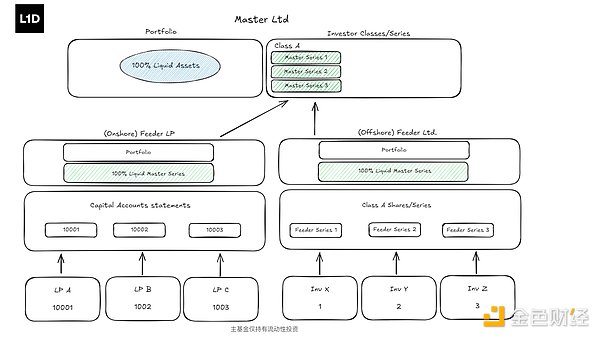

Side Pocket Structure Sample The structure sample chart below reflects the general way investors allocate side pocket risk exposure.

For the sake of illustration, we use an offshore feeder limited partnership as an example because it uses share class accounting and is more suitable for illustrating certain key points related to this accounting concept and its application to side pocket accounting. A similar mechanism is also used for an onshore feeder limited partnership, but no details are reflected in this example.

The Master Fund makes and holds actual cryptocurrency investments in its portfolio. Each Feeder Fund invests in the Master Fund's share classes and is a shareholder of the Master Fund.

Investors in the feeder fund will receive shares of the feeder fund - a feeder fund is a fund that accepts subscriptions monthly, and when an investor subscribes in a particular month, a series will be created for that month to properly account for and track performance and calculate the corresponding incentive fee. Investors in the feeder fund share the performance of the master fund portfolio through the change in the value of the feeder fund's investment in the master fund shares and the corresponding increase in the value of their feeder fund shares.

When the Master Fund holds only liquid assets, the Sub-Fund investors have an indirect proportionate share of the entire Master Fund's liquid assets. In this case, 100% of the Master Fund's shares are liquid, and in return, the Sub-Fund shares are also liquid and eligible for redemption in accordance with the Fund's terms. The performance of their Sub-Fund shares will be 100% based on the performance of the Master Fund's shares and ultimately on the performance of the Master Fund's portfolio (specific performance is explained at the series level).

As shown in Figure 1 below, the master fund only holds liquid investments in January, and all performance will be distributed to the connected investors. All connected series will benefit from the performance of the master fund, and each identical series (i.e. subscribed in the same month) will have the same performance.

Figure 2 shows a master fund portfolio that determined that 10% of its portfolio was illiquid in February.

When a portion of the Master Fund's portfolio becomes illiquid, those assets cannot be sold to satisfy redemption requests from Sub-Fund investors. Asset illiquidity can occur for two main reasons - either certain assets become illiquid due to some form of distress, or the Master Fund invests in illiquid assets due to special opportunities. In either case, Sub-Fund investors who invest only when illiquid assets enter the Master Fund's portfolio should be exposed to those illiquid assets - both from a fee and performance perspective, and from the perspective of changes in the liquidity of their holdings.

To address some of the current illiquidity in the portfolio, the Master Fund will create a side pocket in February to house these illiquid assets, and only Master Fund investors who invested before February will be eligible to invest in this side pocket - they will receive benefits from the future performance of the side pocket, and crucially, after the creation of the SP (which will be done by converting 10% of their liquid shares into SP shares), only 90% of the shares will be eligible for redemption (as 10% of their initial liquid shares have been converted into SP shares). Investors who subscribed to the Master Fund in March will not invest in the side pocket created in February.

The master fund will create a special share class to hold the side pocket assets - the SP class. When this happens, the feeder fund portfolio will hold 2 assets (liquid master shares and non-redeemable master SP shares) and must also create a side pocket share class to hold illiquid exposures such as master fund SP shares. This is to ensure proper accounting and liquidity management to match the master fund's liquid exposure, as the investor's investment date is critical in determining their exposure, performance and fees. When a feeder investor redeems (only from the liquid class, i.e. Class A shares), the feeder fund will redeem some of the liquid shares from the master fund to raise the redemption proceeds for the redeeming investor. Feeder SP shares (like master SP) are non-redeemable.

A separate accounting of each side pocket and corresponding grade is required to ensure fair distribution of value.

In this structure, investors in the offshore feeder fund have their accounting and legal exposure aligned with that at the master fund level (a similar mechanism also exists for investors in onshore feeder funds). This ensures that only actually liquid assets are sold at the master fund level to raise cash to pay for redemptions at the feeder fund level.

Investors in the offshore feeder will receive an investor statement reflecting their liquidity category and side pocket category so that they know what their total capital is and what is available for redemption.

Many managers and service providers are not well-informed about such accounting and appropriate structures, and close coordination between investment managers, legal advisors, fund administrators and auditors is essential to ensure that structures and rights are enforceable and compatible with the terms of the offering documents.

Governance

Board of Directors – It is good governance to have an independent member on the fund’s board and there should generally be a majority of independent directors, e.g. more independent directors than affiliated directors (e.g. the CEO and/or CIO). Typically, directors for offshore funds are provided by firms in the fund’s location that specialize in providing such corporate services. If possible, it is best to have an independent director with real operational experience and expertise, which can add value when dealing with complex operational issues – these individuals can also add value in an advisory capacity rather than as a formal director.

Independent boards are becoming more common for newly launched crypto funds, but the associated costs of the directors are borne directly by the funds.

Side Letters - A fund may enter into side letter agreements with certain investors to provide investors with certain rights that are not directly set forth in the fund's offering documents. Side letters should generally be reserved for large, strategic and/or early stage investors in a fund. Side letters may include provisions related to information rights, fee terms and governance items.

Regulatory status

Funds are usually regulated by local corporate or mutual fund laws. In the United States, even if a fund is exempt from registration with the SEC under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and the investment manager is not a registered investment advisor (RIA), other regulators such as the SEC and CFTC may still conduct supervision and enforcement.

Newer fund managers generally choose to be treated as an Exempt Reporting Adviser (ERA), which has much lower reporting requirements. In the US, the fund will fall into a category defined for private funds under the Investment Company Act of 1940. Two common categories are 3(c)1, which allows fewer than 100 investors, or 3(c)7, which allows only qualified purchasers (individuals with $5 million of investable assets and entities with $25 million of investable assets). Many new funds choose to be 3(c)1 due to the lower reporting requirements, however, fund managers must recognize that due to the limited number of investors allowed, they may not want to accept small subscription amounts in order to manage this investor "budget" in terms of the number of investors the fund can accept.

Under the Securities Act of 1933, private funds can raise capital through Rule 506(b), which permits raising capital but prohibits broad solicitation, and Rule 506(c), which permits broad solicitation but comes with heightened reporting requirements.

Establishing an entity typically requires hiring legal counsel in each jurisdiction and making corresponding filings as well as ongoing maintenance and compliance.

Physical subscription and redemption

The fund may choose to accept subscriptions from investors in cryptocurrencies (physical).

In some cases, funds may be permitted to pay redemptions in kind - this is generally not a preferred option and may create regulatory and tax issues as investors may not have the technical capacity to custody the assets or may not be permitted to hold crypto assets directly from a regulatory perspective.

Physical subscriptions may bring valuation, tax and compliance issues. Typically, physical subscriptions are only accepted in BTC or ETH to avoid valuation issues. In terms of taxation, in the United States, physical subscriptions may trigger a tax event for investors, which should be considered. In terms of compliance, physical subscriptions will be wallet-to-wallet transactions, so fund managers as well as fund agents accepting subscriptions should have the ability to perform appropriate KYC on the sending wallet address, and investors should be aware of this. If the fund does accept physical subscriptions from investors, when that investor redeems, from an anti-money laundering perspective, the best practice is to pay the redemption amount in kind, where the subscription amount is paid in kind and any profits are paid in cash.

Key Person Risk

Key person provisions allow investors to redeem funds outside of the normal redemption window if a key person (such as the chief investment officer) becomes incapacitated or is no longer involved in the affairs of the fund - the inclusion of such provisions is considered best practice.

Case Studies

The following case studies highlight choices embedded in fund structures and reflected in offering documents that resulted in negative or potentially disastrous consequences for investors. It is understood that these choices were made by the respective fund managers with the best of intentions, often to achieve operational and cost efficiencies.

Side pockets

A fund provided side pocket investments to investors but did not create legally separate side pocket investments and only accounted for the side pocket investments on an accounting basis.

The intentions of the manager and the fund are clear and the accounting is correct.

However, because no legal side pockets were established, investors in the fund were theoretically and legally able to redeem their entire balances—including both liquid and illiquid side pocket holdings—and were legally entitled to their entire balances under the terms of the fund documents.

Investors received investor statements that did not reflect the side pocket category (because none was created) and therefore may have believed that their entire reported NAV was available for redemption.

If a fund's large investors do make such redemptions within their legal rights, this would force the fund manager to liquidate illiquid assets on extremely unfavorable terms, to the detriment of remaining investors, and/or sell the fund's most liquid assets, leaving remaining investors holding the least liquid assets and exposing the entire fund to the risk of collapse.

Ultimately, this was rectified by providing clear definitions in updated fund legal documents, establishing formal and legal side pockets, and conducting appropriate investor reporting.

It is worth noting that the issue was discovered by L1D.

The fund's manager, auditor, fund administrator and legal advisor all considered the structure originally designed and implemented to be reasonable and appropriate. A further lesson is that even experienced service providers may not always be right and managers themselves must acquire such domain knowledge.

Structuring

The strategies that L1D intends to invest in are actually classes of shares of a large fund (an “umbrella fund”) that offers various strategies through different classes of shares. Each class of shares has its own fee terms and redemption rights.

An umbrella fund is a standard master-slave fund structure.

On the surface, this appears to be a way to save costs and execution fees by scaling various strategies through a single fund structure. However, one of the stipulations in the “Risks” section reads:

Cross-class liability. For accounting purposes, each class and series of shares will represent a separate account and separate accounting records will be maintained. However, this arrangement is binding only among the shareholders and not on creditors outside the fund who deal with the fund as a whole. Thus, all of the fund's assets may be used to pay all of the fund's debts, regardless of to which individual portfolio those assets or debts are attributed. In practice, cross-class liability generally only arises in the event that any class becomes insolvent or exhausts its assets and is unable to pay all of its debts.

What does this mean? It means that if the umbrella fund faces liquidation, the assets of each unit class will be considered assets available to the umbrella fund's creditors, which could wipe out the assets of each unit class.

What happened? The umbrella fund was eventually liquidated due to poor risk management, and the assets of each share class (including the specific share class L1D that was considered an investment opportunity) were swept into the bankruptcy estate. The fund and the assets of that share class subsequently became the subject of extensive litigation, leaving investors largely powerless and prospects for recovery uncertain.

Risk management failures at the investment level lead to bankruptcies, and weaknesses at the operational/structural level lead to further capital losses for investors who were not exposed to actual failed strategies. Poorly considered structural decisions and relatively mediocre representation in PPMs lead to large losses for investors in stress situations. Although not intentionally hidden, risks are actually hidden in PPMs and become key risk factors.

Under that structure, L1D transferred the investment during initial due diligence.

Accounting Leverage

The following case study excerpt provides a view of the risks when attempting to apply different strategies implemented at the share class level rather than by individual funds, each with its own assets and liabilities. The narrative is very similar to the previous example – a failure to manage risk in the investment process is exacerbated by structural weaknesses.

The fund offers both leveraged and unleveraged versions of its strategy through share classes within a single fund.

The fund is a single pool and all collateral is traded against a single legal pool with the fund’s counterparty – all gains and losses are attributed to the entire fund and the manager allocates gains and losses on an accounting basis based on share class leverage.

The fund’s strategy and corresponding risk management processes changed without notifying investors, coinciding with a significant market event that effectively wiped out the fund’s collateral with its counterparties, leading to mass liquidations.

Investors in the unleveraged share class can expect to suffer large losses, but not lose everything, based on the leverage ratio defined for the share class. Similarly, the cross-liability risk expressed in the PPM conveys this risk, but investors in the unleveraged share class are not well aware of it.

The fund’s failure was the result of a combination of events – uncommunicated strategy changes, poor risk management, coupled with market tail events, combined with structural choices where investors who were intended to invest unlevered were still subject to the application of leverage.

NAV reporting delays See Service Providers section, Fund Managers

3. Manipulating the stack

The operational system is defined here as all the functions and roles that the manager must undertake to execute its investment strategy. These functions include trading, fund management, counterparty management, custody, middle office, legal and compliance, investor relations, reporting and service providers.

Trading activity in TradFi has several dedicated parties involved to ensure secure settlement and ownership - the diagram below reflects the parties involved in US stock trading.

In cryptocurrency trading and investing, trading venues and custody form the core infrastructure as their combined functionality forms the parallel architecture of the TradFi settlement and prime brokerage models. Since these entities are at the heart of all trading, all processes and workflows are developed around interacting with them. The following diagram illustrates the roles played by prime brokers and the services they provide.

In TradFi, a key function of a prime broker is to provide margin, collateral management, and netting. This enables funds to achieve capital efficiency across positions. For this service, prime brokers can often re-hypothecate client assets in custody (e.g., lend securities to other clients of the PB).

While prime brokers play a key role in managing counterparty risk, they are also risky themselves as they are the fund’s primary counterparty. Rehypothecation services mean lending out client assets, and if the prime broker goes bankrupt for any reason, the fund’s clients will become creditors, as rehypothecation means that client assets are no longer the client’s property.

In the crypto space, there are no brokers that bear a direct resemblance to a TradFi prime broker. OTC desks and custodians are attempting to fill this role, or aspects of it, in different ways. FalconX and Hidden Road are two examples. However, the prime broker business in crypto is still evolving given the different nature of crypto (particularly because the underlying assets are on different blockchains that are not necessarily interoperable), the more limited reporting systems of exchanges, and the spread of operations across different jurisdictions. Most importantly, the motivation for an entity to become a prime broker in the first place is to be able to rehypothecate client assets, which is a clear aspect of their business model. Prime broker failures during the global financial crisis demonstrated that prime brokers themselves pose counterparty risk to their hedge fund clients. This counterparty risk is magnified in crypto because brokers and exchanges are undercapitalized, have less risk management oversight from regulators or investors, and are not bailed out in a crisis. This problem is further exacerbated by the inherent volatility of crypto and the resulting risk management challenges. These factors make it difficult to apply the TradFi prime broker model to crypto in a “safe” way from a counterparty risk perspective.

The prime broker model helps define the operational stack for a cryptocurrency investment manager, as the manager takes on much of the functions of a prime broker in-house, and/or consolidates various functions from multiple service providers and counterparties. These roles and skills are often both in-house and outsourced, but given the nature of the service providers available in the space, it should be expected that much, if not most, expertise is in-house, with domain knowledge on the manager’s side being critical.

Operational Stack — Crypto Hedge Fund

The following are the main operational functions in a crypto hedge fund. It is still important to maintain a certain level of separation between operations and investing/trading, which is usually applicable to the signing policy involving the movement of assets.

Middle/back office: Fund accounting, trading and portfolio reconciliation, NAV production – often responsible for supervising and managing fund managers.

Financial management: managing cash and equivalents, exchange collateral, stablecoin inventory, banking relationships.

Counterparty management: Conduct due diligence on counterparties (including exchanges and OTC desks), conduct onboarding training and negotiate commercial terms with counterparties, establish asset transfer and settlement procedures between fund custody assets and counterparties, and set risk exposure limits for each counterparty.

Custody and Staking: Internal non-custodial wallet infrastructure, third-party custodians - including establishing whitelisting and multi-signature (“Multisig”) procedures, maintaining wallets, hardware and related policies and security regulations, and performing due diligence on third-party custody providers.

IT and Data Management: Data systems, portfolio accounting, backup and recovery, cyber security.

Reports: internal reports, investor reports, audits.

Valuation: Development and application of valuation policies.

Legal and Compliance: Manage external legal counsel, internal policies and procedures, and handle regulatory filings (including AEOI, FATCA, AML/KYC and other matters).

Service provider management: due diligence on service providers, review and negotiation of service agreements, and service provider management with a focus on fund managers.

Operational Role

In light of the above operational functions and responsibilities, when considering the appropriate skills for an operations staff member (typically a Director of Operations and/or Chief Operating Officer), the required skills will include experience in these areas and may further depend on the fund's strategy and underlying assets. The required experience generally falls into two categories:

Accounting and auditing – Applicable to all funds, but most critical for funds with high turnover, many projects, and complex equity structures (e.g. side pockets).

Legal and structural – applies to funds trading structured products and strategies with tax and regulatory components, often some form of arbitrage.

In both cases, if there are gaps in the expertise of an individual, such as an accountant without a legal background, these gaps are often filled by an external body (e.g. legal counsel). However, it should be noted that fund managers in this area (as will be discussed in more detail below) often require a significant amount of oversight and supervision in the pre-launch and first 3-6 months post-launch, and individuals and/or accounting professionals with experience and background in fund operations, fund management or dealing with fund managers are often well suited to manage this.

As a best practice, the investment manager is able to maintain a set of shadow fund records that effectively act as a shadow, mirroring the records maintained by the fund administrator. This enables a three-way reconciliation between the investment manager, the fund administrator and the financial counterparty. The three-way reconciliation is performed at the end of the month to ensure that all records are consistent and match.

Overview of Fund Operating Entities

Asset life cycle

The flow of assets from subscription to fund, transaction and redemption illustrates the operational stack. The following generic lifecycle shows the operational touchpoints:

Investors' subscription funds are transferred to the fund's bank account

Investor subscription funds will be transferred to the fund's bank investor account and transferred to the fund's trading or operating account after KYC/AML clearance.

Fiat is transferred to a fiat on-ramp (exchange or OTC) and exchanged for (usually) stablecoins; typically the fund administrator must be a second signatory on the transfer of fiat out of the bank account.

Stablecoin balances can be held on exchanges and/or in third-party custody.

Investment Committee/CIO decides on deals/investments

Pre-trade clearing for compliance (i.e. personal trading policy) and/or risk management purposes.

Traders source liquidity through a counterparty (exchange or OTC), specify the order type, i.e. market/limit/stop, and possible execution algorithm, i.e. TWAP/VWAP.

Interact with counterparties via API, portal or chat (i.e. Telegram).

If an exchange trade is conducted on a listed asset, the stablecoin balance is used and the settlement assets are transferred to a third-party escrow.

In OTC trading, some trades may be pre-funded, or the OTC desk may provide some credit - the order is filled, settled, and then the assets are transferred to escrow.

In case of perpetual swaps - maintain collateral balance with the exchange and make regular payments.

Clearing and Settlement – Verifying transaction details as they settle; transferring assets to storage/custody after a trade is settled.

The investment team assesses the impact on risk exposure and risk parameters.

The Operations department reconciles all positions daily - assets, account balances (counterparty, custodian, bank), prices, quantities, price references, calculates portfolio profit and loss; and publishes internal reports.

Provide transaction documents and reconciliation packages to fund managers at the end of the month

Fund managers independently verify assets and prices with all counterparties, custodians, banks – typically manually, via APIs, OTC desk support (i.e. TG chat extracts) and/or using third-party tools (e.g. Lukka), apply fees and expense accruals.

The investment manager works with the fund administrator to resolve differences in the reconciliation and calculate the final NAV.

The fund manager uses an internal quality assurance/QA process to calculate the fund's NAV and investors' NAV.

The Fund Administrator provides the Investment Manager with the final NAV proposal for review and signature and issues an Investor Statement.

Investor Redemption

Investment assets are transferred from custody to the exchange/OTC market and converted into fiat currency and sent to the fund bank investor’s account.

After NAV approval

The fund manager authorizes the payment of redemption funds to redeeming investors.

Broad counterparty flows

This diagram reflects the process described in the asset life cycle.

4. Trading venue and counterparty risk management

Since the FTX debacle, funds have reevaluated their approach to managing counterparty risk, specifically whether to keep assets on any exchange, as well as managing exposure to any entity that holds fund assets at any time, including OTC desks, market makers, and custodians. Exchange custody is a form of custody (covered in more detail in the custody section) where an exchange holds customer assets that are commingled with the exchange's assets and are not bankruptcy remote. Funds hold/hold assets on exchanges because it is easier, more economical, more efficient, and more capital efficient to do so.

It is also worth noting that agreements with OTC trading platforms provide for “delivery and payment,” whereby customers pay before assets are delivered. Furthermore, these agreements typically provide for such assets to be commingled with other customer assets, rather than separated or bankruptcy-remote. Therefore, there remains the risk of an OTC counterparty defaulting before assets are delivered. During the FTX collapse, certain OTC trading platforms themselves had unsettled customer trades with FTX. These OTC trading platforms became creditors for FTX assets and chose to pay customers in full from their own balance sheets, even though they had no obligation to do so. Formal underwriting of exchanges and OTC counterparties has been difficult because financial statements are not necessarily available and can be of limited use, although transparency is improving.

Counterparty Risk Management Approach

To properly manage counterparty risk, investment managers should develop policies that are compatible with their investment strategy. This may/should include defining:

The maximum exposure allowed to any counterparty.

Maximum exposure allowed to any counterparty type (exchange, OTC, custodial).

Allow maximum exposure for any sub-category – qualified custodians vs. others.

The maximum time limit for a trade to settle - usually expressed in hours.

The percentage of a fund's assets that may be outstanding at any given time.

Other measures can be taken to monitor the health of counterparties, including "pinging" counterparties with small transactions from time to time to test response times. If response times are outside normal ranges, managers may transfer risk away from that counterparty. Fund managers continuously monitor market activity, news, and wallets of major players to identify unusual activity, thereby avoiding any potential defaults and transferring assets.

DeFi Considerations

Decentralized exchanges (“DEXs”) and automated market makers (“AMMs”) can complement a fund’s counterparty universe and, in some cases, act as substitutes. While some centralized players have struggled, their DeFi counterparts have fared relatively well.

When interacting with DeFi protocols, the Foundation trades counterparty risk for smart contract risk. Generally speaking, the best way to cover smart contract risk is to determine the risk exposure in the same way as defining counterparty risk limits (as described above).

Additionally, there are access and custody issues to consider when interacting with DeFi protocols, which are covered in more detail in Section 6, “Custody”.

Tripartite Structure

To manage counterparty risk associated with exchanges, some service providers have developed innovative approaches. These approaches implement a tripartite structure. The solutions detailed below have gained wide acceptance.

As the name implies, this arrangement involves at least three parties – the two parties transacting with each other, and a third party – an entity that manages the collateral for the transaction, usually a custodian. This third party will monitor and manage the collateral assets involved in the transaction.

A key feature of this structure is that the party managing the collateral maintains the assets in a legally segregated manner, often a trust, to protect the parties to the transaction from the entity managing the collateral and protecting the structure.

Under this structure, the entity managing the collateral ensures delivery and payment by both parties, and then settlement takes place.

As part of this process, excess collateral is posted or returned based on margin requirements, reports are provided to both parties, and assets are continually monitored to ensure they are sufficient to satisfy the financial transactions between the parties.

Copper ClearLoop

Copper Technologies enables OTC or custodial settlement through its ClearLoop product. In this setup, both parties (fund client and exchange counterparty) actually post collateral to Copper (and such collateral is held in a trust), while the trust acts as a neutral settlement agent on behalf of both parties. This protects the fund from the risk of exchange counterparty default, where the principal (collateral) is protected, but there is still a risk of profit or loss if the counterparty defaults before the (winning) trade is settled.

Copper was an early innovator in this type of setup, leveraging its custody technology and existing exchange integrations.

All other major custodians, including Anchorage, Fireblocks, Bitgo, Binance, etc., are working on their own forms of tripartite agreements using legal structures and technology, and/or may be working with Copper.

Hidden Road

Hidden Road Partners (HRP) has developed a prime brokerage business that provides a form of capital efficiency and counterparty risk protection. HRP raises capital from institutional investors and pays them a return on capital, which is generated by financing trades for clients. HRP mitigates risk by setting risk limits and requiring a certain percentage of collateral to be posted upfront. Clients can then net positions across trading venues.

In this framework:

The Fund is not required to post collateral to an exchange or trading partner.

The counterparty risk is transferred to the HRP's balance sheet.

The transaction was recorded under ISDA and standard Prime Brokerage protocols.

Clients can build margin portfolios across trading platforms.

5. Treasury — Fiat Currency and Stablecoins

The treasury function in a crypto HF is usually a combination of managing a small fiat balance and a stablecoin inventory. Once an investor subscription is accepted, they typically redeem it for stablecoins through a fiat onramp (exchange or OTC desk). Considerations for the treasury function are as follows:

Banking Partners

Stablecoins

Banking Partners Crypto HFs typically maintain very low fiat balances, as most activity is transacted in cryptocurrencies (usually stablecoins). Nonetheless, all crypto HFs require sophisticated banking partners to accept investor subscriptions, fund fiat fees, and pay service providers. The list of banking partners willing to work with crypto clients is growing, but the onboarding process can be cumbersome from an AML and KYC perspective, often taking months to complete.

Given that banks’ willingness to work with crypto clients varies based on their respective risk appetites, funds should work with at least two banking partners for redundancy. When Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and Silvergate Bank failed, many funds lost their banking partners and were unable to reliably conduct certain operations, including redemptions of funds that had been arranged and accepted before the failure of these banks.

The onboarding process requires a lot of documentation, either through a portal or by direct submission. From the bank’s perspective, the goal of the process is to ensure that the client does not pose any risk from an AML and KYC perspective. To achieve this, the bank will conduct due diligence on the fund structure, its UBOs (ultimate beneficial owners), controllers (e.g. directors) and investment managers. Funds and investment managers with more complex management and ownership structures should be prepared to explain the relationships between the various entities – it is useful to prepare an organizational chart for this purpose.

Below is a standard set of documents required by (US) banks to initiate the process. These documents are pretty standard but themselves may contain up to 100 basic questions related to fund operations, investment managers, all service providers, and potential investors. In addition, once onboarded, there are usually ongoing/annual compliance activities that may amount to re-onboarding.

Bank Partner Onboarding Document Requirements

Account Application

Due Diligence Questionnaire

Certificate of Incorporation – usually notarized or certified

Private Placement Memorandum

Articles of Association or Limited Partnership Agreement

Financial Statements

Register of Directors

Commercial Register Extract

W-BEN-E

FATCA Number — GIIN

U.S. Tax Identification Number

Passport/driving license of the account signatory and authorized user

Proof of beneficial ownership

Passport/driving license/residence certificate of all underlying beneficial owners (UBO, > 10% or 25%)

Regulatory registration status

Service agreements with key service providers (fund administration, compliance, directors)

Stablecoins are an integral part of cryptocurrency trading. Stablecoins also present certain operational risks. Stablecoins themselves, especially USDT/Tether, are regularly subject to concerns about regulation, support, depegging, and possible cessation of redemptions (although this has never happened). Therefore, it is wise to diversify your stablecoin inventory among several stablecoins.

Bank partners do not typically enforce minimum monthly balances, but also do not typically offer a full suite of services for small fund accounts, including the ability to purchase and hold U.S. Treasuries. As a result, funds may choose other forms of stablecoins, including Ondo (a tokenized note backed by short-term U.S. Treasuries and bank deposits), or similar products offered by Centrifuge that include real-world assets/RWAs. Yield-generating stablecoin products may present their own risks, and the