Editor's Note

George Selgin is a senior fellow and director emeritus of the Cato Institute's Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives, and an emeritus professor of economics at the University of Georgia. His research covers a wide range of topics in monetary economics, including monetary history, macroeconomic theory, and the history of monetary thought.

Selgin is one of the founders of the modern free banking school, which draws inspiration from F.A. Hayek's writings on denationalization of money and monetary choice, and which he co-founded with Kevin Dowd and Lawrence H. White.

The Cato Institute is a libertarian think tank located in the United States, dedicated to promoting the ideas of limited government, individual liberty, and free market economics. The Cato Institute's funding comes from the main Republican donor Charles Koch.

The following is the main content:

The "Digital Gold" Fallacy: Why Bit cannot save the Dollar

This summer, the Bit story took a major turn. Bit was initially seen as a revolutionary, grassroots alternative to traditional fiat currencies, including the US Dollar. However, this turn has made Bit's role not to oppose the Dollar, but to strengthen the Dollar's position as the world's most popular medium of exchange.

While this new perspective has earlier roots, it gained widespread attention at the Bit 2024 conference in July. The conference featured proponents of this view, including presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Donald Trump.

Just like the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, these proposals come in three different sizes. Trump's proposal is the most conservative, suggesting that the federal government use its already-owned 210,000 Bit - most of which were seized by law enforcement - as the "core" of a "strategic national Bit reserve," claiming this would "benefit all Americans."

Kennedy's plan - the "Big Bear" proposal - would add 550 Bit per day to Trump's "core," until the Treasury holds at least 4 million Bit, more than a fifth of the current circulating supply. According to Kennedy, his plan would make the value of the Bit held by the US Treasury, at current market prices, exceed its gold reserves, putting the US in a "position of dominance that no other country could replicate."

Finally, the "Mama Bear" proposal was put forth by Wyoming Senator Cynthia Lummis after Trump's keynote speech. Her proposal is for the US Treasury to establish a "Bit strategic reserve" including purchasing 1 million Bit over five years. Unlike the other proposals, Lummis' plan has already found its way into actual legislation, the BITCOIN Act of 2024, which Lummis introduced just days after the Nashville conference. One of the act's purposes is to "strengthen the Dollar's position in the global financial system."

If it were just politicians proposing to establish an official US Bit reserve, this could be seen as opportunistic attempts to capitalize on Bit's popularity for electoral gain. But given the applause these three proposals received at the Nashville conference, and the commentary afterward, many Bit supporters seem to believe that the proposed Bit reserves would genuinely benefit the Dollar and the US economy as a whole, regardless of whether Satoshi Nakamoto himself would endorse these proposals.

Politicians are not the only ones calling for the US government to join the Bit bandwagon. In a recent report, "Digital Gold: Assessing a US Strategic Bit Reserve," the Bit Policy Institute also recommends that the US establish a Bit strategic reserve as a "unique complement to traditional reserve assets (like gold and Treasuries)" to help "ensure the Dollar's continued dominance."

Why the Need for Reserve Assets?

So, is it time to bid farewell to the Dollar as the "Terminator" and welcome Bit as the Dollar's "Turbocharger"?

Not quite. Some see the idea of an official Bit reserve strengthening the Dollar as distinct from viewing Bit as a strategic commodity like oil and silicon chips, or hoping the US government will incorporate Bit into a sovereign wealth fund. While the calls for a strategic Bit reserve often conflate these different arguments, this article focuses solely on the "monetary reserve" argument. Would government accumulation of Bit truly "turbocharge" the Dollar? Can a strategic Bit reserve be compared to the role of gold reserves in the US and elsewhere? Does the Dollar really need "turbocharging" to maintain its global status?

To answer these questions, we must understand the general role of non-domestic reserves in supporting today's fiat currency system, especially the Dollar's role. Official reserve assets are financial assets held by fiscal or monetary authorities that cannot be self-created by those authorities. Today, these assets are typically foreign exchange (including the foreign currencies themselves, as well as bank deposits and securities denominated in foreign currencies) and gold. According to IMF data from mid-2024, the world's monetary and fiscal authorities collectively held $12.347 trillion in foreign exchange assets and 29,030 tons of gold, worth around $2.2 trillion.

Why do governments hold reserves? In the commodity money era, central banks and commercial banks needed reserves of the monetary commodity to meet redemption requests from customers and other banks. When many countries' currency systems were based on the same commodity standard, as in the pre-Great Depression gold standard era, reserves were also needed to cover international payments deficits, that is, the positive difference between a country's net foreign outflows and its current account receipts (exports minus imports and net remittances).

In today's irredeemable fiat currency systems, reserve assets are clearly no longer needed to redeem central or commercial bank liabilities. Commercial bank deposits are effectively claims on central bank currency, or central bank reserve credit in interbank settlements. As long as countries are willing to let their exchange rates float freely, they can eliminate international payments deficits through exchange rate adjustment without using foreign exchange reserves.

However, in practice, even countries issuing their own fiat currencies often seek to peg the value of their currency to that of another country. For example, small open economies often choose to peg their currency to that of their major trading partner to avoid trade counterparties facing exchange rate risk. In such cases, foreign exchange becomes necessary again to cover international payments deficits. Other countries aim to limit fluctuations in their currency's exchange rate, using "managed float" or "dirty float" regimes rather than fixed or freely floating rates. These countries also need to hold a certain amount of foreign currency as reserves.

On the other hand, gold reserves are no longer used to settle international accounts. But they still make up about 15% of global reserve assets. The main reason is that gold is a good hedge against exchange rate or "monetary" risk, the risk that monetary authorities bear by holding foreign exchange reserves. When held as bullion in the home country rather than in foreign custody, it is also not subject to the political risks that foreign exchange reserves may face, such as being frozen or confiscated by foreign governments.

But as we will see, the holding of most official gold reserves has little better justification than inertia. These reserves include the 8,133 tons held by the US - about two-sevenths of the global total - which are almost entirely accumulated from the US's time on the gold standard.

The US Dollar as a Global Reserve Asset

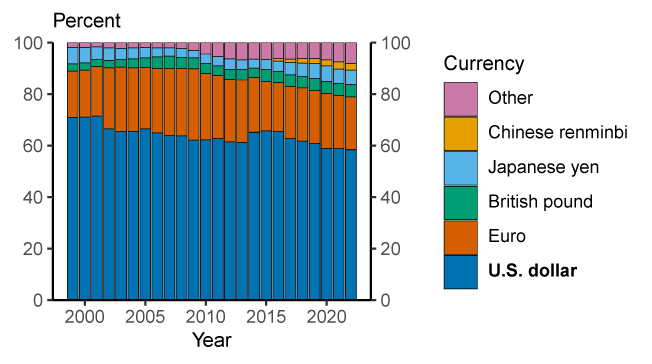

Although the global foreign exchange reserves include the currencies of many countries, the US dollar's share far exceeds that of other currencies, accounting for about 58% of the total reserves. The euro follows closely, accounting for 20%. As shown in the chart below, a few currencies - the Japanese yen, British pound, Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, and Swiss franc - occupy the remaining large portion. Other currencies, if used as reserves, only account for a negligible share.

Currency Composition of Global Foreign Exchange Reserves

The dominance of the US dollar is no mystery. According to the latest commentary from the Brookings Institution, the US dollar also accounts for 58% of all cross-currency payments, meaning that 58% of international payments between non-euro area countries use the US dollar. Additionally, 64% of global debt is denominated in US dollars, including about $13 trillion in US dollar credit extended to non-bank borrowers outside the United States. These data also explain why many foreign governments are more willing to peg their currency exchange rates to the US dollar, or at least limit exchange rate fluctuations, even though this forces them to hold large US dollar reserves.

If the US dollar's position is so entrenched, why do some believe it needs to be strengthened? The root of this view is that the US dollar's share of global reserve assets has declined by 12 percentage points since the late 1990s. If this decline is accompanied by a rise in the share of the euro, yen, or even the British pound (the only other serious contender), and this trend is likely to continue, it could ultimately threaten the US dollar's reserve currency status. And if this decline reflects a reduction in the volume of trade denominated in US dollars, it could also indicate a decrease in the US dollar's popularity as a medium of exchange. However, this is not the case. The weakening of the US dollar is not due to its replacement by competitors like the euro or yen, but rather by various "unconventional" reserve currencies, including the Canadian dollar, renminbi, and gold. Moreover, this weakening is not due to more trade being priced in unconventional currencies or gold - for example, cross-border renminbi payments are far smaller than US dollar payments - but for other reasons, including the "weaponization" of the US dollar by the US government, i.e., through sanctions freezing or seizing foreign governments' US dollar reserves held in US financial institutions or those cooperating with the US.

Clearly, establishing a strategic Bit reserve would not alleviate the risk of foreign governments' US dollar reserves being seized. Perhaps less obvious is that such a reserve would not provide any support for the value of the US dollar or increase its popularity at all.

The United States' Reserve Assets

As of October 2024, the US Treasury and Federal Reserve System held $245 billion in reserve assets. In addition to foreign exchange (over $37 billion, about two-thirds in euros and the rest in Japanese yen), and 8,133 metric tons of gold (valued at about $11.04 billion at the official gold price of $42.22 per ounce, or around $691 billion at the current market price), these reserve assets include the US's reserve position in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (about $29 billion) and its allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) (less than $170 billion).

Looking at this total, the US's stock of reserve assets places it in the "second tier" globally. Despite being the world's largest economy, this total reserve amount ranks only 15th globally, behind countries like Hong Kong, Singapore, and Italy.

While this raw ranking may not be very impressive, it greatly overstates the US government's emphasis on these assets, as the IMF reserves and SDRs account for over 80% of the total US reserve assets. This is because, while the Treasury and Federal Reserve jointly decide how much foreign exchange and gold to hold, the US's IMF reserve position and SDR holdings are set by IMF rules. For example, the IMF periodically sets the total SDR allocation for all its members, which is then distributed according to each member's quota share in the Fund.

The US's large SDR holdings mainly reflect the IMF's recent $660 billion (about $890 billion) total allocation, and the US's 17.42% quota share. The US's IMF reserve position is similarly a mandatory amount, representing part of each IMF member's compulsory contribution to the Fund. Stripping out the SDR and IMF reserve holdings from countries' total reserve assets, the US's ranking drops to 45th, behind Vietnam, Romania, Colombia, and Qatar! As we will see, even in this ranking, the importance of the US's international reserve assets is overstated, because, unlike most central banks' gold holdings, the US's gold reserves (which, incidentally, belong to the Treasury, not the Federal Reserve) have no strategic significance.

The US's meager reserve assets, especially its foreign exchange reserves, reflect the unique status of the US dollar as the most freely floating currency: Other governments may peg their currencies to the US dollar, whether tightly or loosely; but for the US government, maintaining these links has largely been, and for a long time will continue to be, the problem of other governments.

The US government's ability to generally allow its currency to float freely is part of the "exorbitant privilege" it enjoys from the US dollar's status as the national and global medium of exchange. As I mentioned earlier, about 58% of international trade is denominated in US dollars, and the US dollar also occupies a corresponding share of global official foreign exchange reserves. Beyond the US, many countries use the US dollar as their domestic currency. The global demand for US dollars, both official and private, allows the US government to borrow without having to use other currencies, and the US dollar's free-floating status also precludes the need for foreign currency to address US payment imbalances.

The Exchange Stabilization Fund: A Not-So-Successful Precedent

The US dollar's position means the US government actually has no need to hold foreign exchange. Since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1973, the US has not been obligated to participate in the maintenance of any international fixed exchange rate system. Although the Federal Reserve has long been authorized to buy and sell foreign exchange, its mandate, as specified in the Federal Reserve Act, is to promote "maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates," and does not involve stabilizing or managing exchange rates.

Even before the collapse of Bretton Woods, the responsibility for US dollar exchange rate policy primarily rested with the US Treasury Department, with the Federal Reserve assisting in its functions under the Treasury's auspices (the joint Treasury-Federal Reserve foreign exchange market operations reflecting the general balance of the nation's foreign exchange reserves). This arrangement can be traced back to the Gold Reserve Act of January 1934, which required the Federal Reserve to turn over its gold reserves to the Treasury in exchange for gold "certificates," in anticipation of the official valuation of gold being adjusted from $20.67 per ounce to $35 per ounce, a price that was maintained until December 1972, when it was raised to $38. (A few months later, it was raised again, to the current $42.22 per ounce.) In this exchange, the Treasury gained a nominal profit of $2.8 billion, of which $2 billion was used to establish an "Exchange Stabilization Fund" (ESF), intended to "stabilize the exchange value of the dollar."

In the book 'Bit Gold', the arguments partially supporting the establishment of a strategic Bit reserve are based on the precedent of the ESF. They argue that the "ESF" provided a tool to stabilize currency markets during periods of exchange rate volatility, helping ensure the dollar maintains its value relative to other currencies. This would allow the US to intervene in foreign exchange markets, mitigate speculative attacks, and prevent abrupt depreciations or appreciations that could disrupt trade balances or financial stability.

Here is the English translation:However, although the ESF was indeed established to "stabilize the US dollar exchange rate", its foreign exchange market intervention has been very limited since 1995, and it has not intervened since March 2011. Why? First, as we have seen, since the floating of the dollar in March 1973, foreign exchange operations have no longer been necessary - this fact was formally (albeit belatedly) confirmed in legislation passed in 1976, which removed the content on stabilizing the value of the dollar from the Gold Reserve Act and changed the function of the ESF to undertake "operations necessary to fulfill the United States' obligations in the International Monetary Fund."

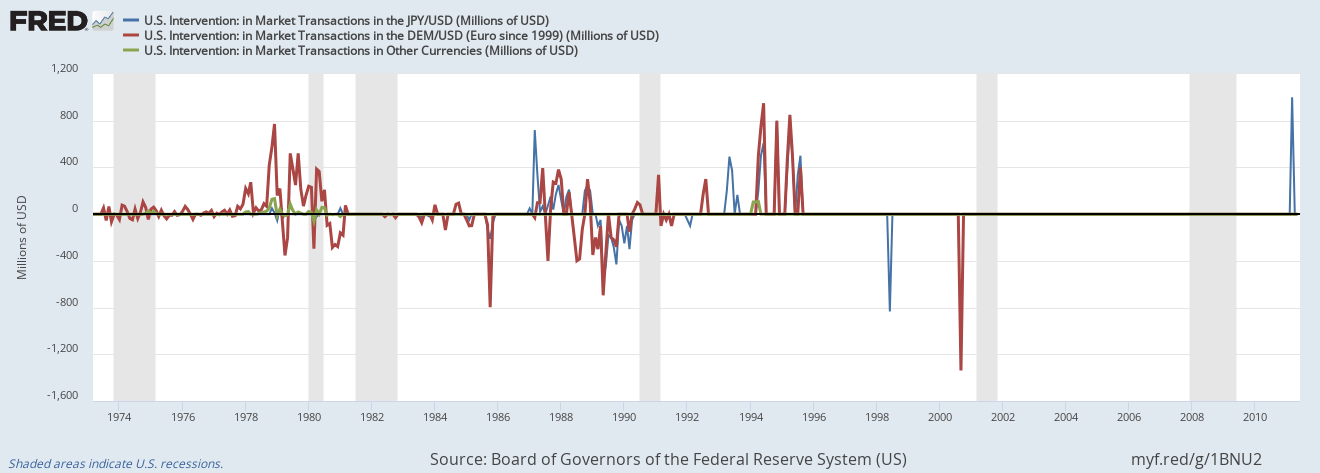

Although the FRED chart below shows that the ESF frequently intervened in the foreign exchange market between the late 1970s and the mid-1990s, using its newly acquired, more ambiguous function, after 1980, its interventions were mostly aimed at weakening the dollar rather than strengthening it. However, it is doubtful whether these interventions had a lasting impact on the dollar exchange rate, as the scale of the interventions was too small compared to the size of the market, and even large-scale interventions could only have a lasting effect if the Federal Reserve allowed the Treasury's exchange rate targets to dominate overall monetary policy.

US Foreign Exchange Market Intervention: 1973-2011

The Federal Reserve did not make such a concession. Instead, the Federal Reserve's determination to fight inflation in the 1980s precluded any form of compromise. As a result, by the 1990s, the US government's exchange rate interventions were mainly "in a spirit of cooperation", such as the US intervening to fulfill its commitments under the 1985 Plaza Accord and the 1987 Louvre Accord, rather than pursuing any US government exchange rate targets.

Since the mid-1990s, even these "cooperative" interventions have become rare: the US intervened in 1998 to support the yen, in 2000 to support the euro, and in 2011 to support the yen to stabilize the Japanese economy after the earthquake and tsunami. But it has not intervened since then. In 2013, the US participated in a G7 agreement to focus its monetary and fiscal policies on domestic policy goals rather than exchange rate targets, and the likelihood of changing this stance appears smaller than ever. Far from serving any strategic purpose, the US's current foreign exchange reserves are more a legacy of past interventions.

Nevertheless, as expected, these developments have not led to the ESF being completely "dead". Before abandoning attempts to influence the exchange rate of the dollar against other major currencies, the Treasury found another use for it, which was to help underdeveloped countries, particularly in Latin America.

The ESF's constitution, its ambiguous post-Bretton Woods era function, and its ability to "monetize" SDRs and foreign exchange reserves (i.e., to temporarily convert them into dollars at short notice) allow it to make large-scale short-term emergency loans without Congressional approval. By the 1990s, such lending had become the ESF's main task. Since the ESF typically makes these loans by "swapping" dollars for foreign currency, they fall within the definition of foreign exchange operations. But stabilizing exchange rates is not the primary purpose of these loans, and in many cases is not the purpose at all.

It is not surprising that Congress takes a negative view of the Treasury using the ESF as a "back door" source of foreign aid. In 1995, Bill Clinton used the ESF to provide a $20 billion aid package to Mexico. Afterwards, Congress tried but failed to significantly reduce the ESF's ability to exchange dollars for foreign currency.

Therefore, although the Exchange Stabilization Fund has not stabilized exchange rates, it has maintained its funding capacity. This has meant that the status of the dollar and the international credibility of the United States have been largely unaffected, despite the fact that the US has not systematically accumulated large foreign exchange reserves for itself.

The Gold Legacy

If the US government does not need foreign exchange, does it still need gold? According to the Bitcoin Policy Institute, in addition to "having historically been an important component of the US global financial strategy, supporting confidence in the dollar, and serving as a hedge against inflation or currency crises", the US's gold reserves also serve as "a last resort financial asset that can be quickly remonetized in extreme circumstances, providing the US with a historically reliable source of liquidity to address severe financial or geopolitical disruptions to the global monetary order." Finally, the gold reserves also allow the government to "discreetly influence the precious metals market, ensuring price stability during periods of monetary or geopolitical turmoil."

There are clearly counterarguments to these claims about the benefits of the US's gold reserves. On the issue of supporting the dollar: "historically" plays a key role here - since the dollar was decoupled from gold in 1971, the value of the dollar has no longer depended on the Treasury's gold reserves. (The value of a freely floating fiat currency, like the value of Bit, is determined by the actual demand and supply for it in the market, not by the assets held by its creator). On the issue of gold's liquidity: nothing is more "liquid" than the dollar itself, as the US can create dollars without relying on gold. On the issue of helping the precious metals market: this is true, the gold reserves do have an impact. But the question is, why should the government support the gold market, other than to allow gold miners and investors to profit at the expense of others?

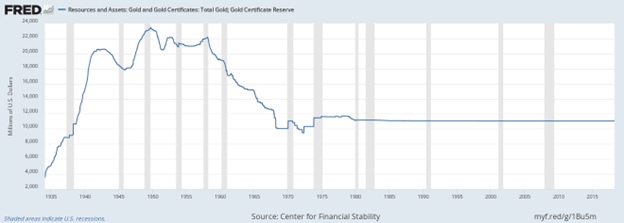

The US Treasury's current gold reserves are far from being deliberately acquired for some strategic purpose, but are a legacy of the US being seen as a unique safe haven for gold after the devaluation of the dollar in January 1934. As the FRED chart below shows, the US's gold reserves increased more than sixfold between the passage of the Gold Reserve Act and the 1950s - a passive accumulation, if not one that officials would regret - reaching a peak of over 20,000 tons. In the 1950s, especially after the Bretton Woods system came into effect in 1958, the flow of gold reserves went into reverse.

When Nixon closed the gold convertibility window in August 1971, the US's gold reserves were less than 8,700 tons. Since then, despite having no obvious use, its quantity has changed very little. However, there is no legal obstacle to the Treasury selling its gold, as long as it repays the corresponding nominal value of the gold certificates held by the Federal Reserve. In fact, the Treasury did sell about 491 tons of gold in the late 1970s to take advantage of the then record-high gold prices. But when a proposal was made in June 2011 to sell more gold to address that year's debt ceiling crisis, the Federal Reserve publicly opposed the plan, arguing that it could not only disrupt the gold market but also affect "broader financial markets". Similar considerations seem to have consistently prevented the US government from selling gold.

US Gold Reserves, 1934-2018

Who Needs Another Unnecessary Reserve Asset?

While the US government has resisted reducing its gold reserves, it has never considered the possibility of increasing them. After all, if the 8,133 tons of gold stored in Fort Knox and elsewhere are merely a legacy of the gold standard and the Bretton Woods era, proposing that the US buy more gold is like suggesting that humans should grow tails because they have tailbones.

Here is the English translation, with the terms in <> left untranslated: So, what about the strategic coin reserves? If the US government's massive gold reserves have no reason to exist merely out of inertia, then it has no reason to acquire bitcoin. (A "second-best" argument is that adding bitcoin to its asset portfolio may reduce the risk associated with gold reserves - the flaw in this argument is that bitcoin is not a particularly good hedge against gold.) In other words, the only reason is to "influence the market in a less sophisticated way", especially by pushing up the price of bitcoin. And - let's be honest - although some bitcoin enthusiasts may sincerely believe that strategic bitcoin reserves will strengthen the dollar, more people support this move not because they care about the future of the dollar, but because they expect it to make them richer, and they don't mind the cost being borne by others.