Author: Decentralised.Co; Translation: Jinse Finance xiaozou

Venture capital as an asset class has always followed an extreme power-law distribution. But because we’re always chasing the latest narrative, the exact extent of this distribution has never been studied in depth. Over the past few weeks, we’ve built an internal tool that tracks the network relationships of all crypto VCs. Why?

The core logic is simple: as an entrepreneur, knowing which venture capital institutions often co-invest can save time and optimize financing strategies. Each transaction is a unique fingerprint, and when we visualize this data, we can interpret the story behind it.

In other words, we can track the key nodes that dominate most of the financing activities in the crypto space. This is like finding hub ports in modern trade networks, which is essentially the same as how merchants searched for trading bases thousands of years ago.

We conducted this experiment for two reasons:

First, we run a VC network similar to Fight Club—no one has thrown any punches yet, but we rarely discuss it publicly. This network includes about 80 funds, while there are only 240 institutions in the entire crypto VC field that invest more than $500,000 at the seed stage. This means that we directly reach one-third of market participants, and nearly two-thirds of practitioners read our content. This influence is far beyond expectations.

However, it is always difficult to track the actual flow of funds. Sending project progress to all funds will cause information noise. This tracking tool came into being, which can accurately screen which funds have invested, which tracks they have laid out, and who their partners are.

In addition, for entrepreneurs, understanding the flow of funds is only the first step. What is more valuable is to understand the historical performance of these funds and their usual co-investors. To this end, we calculated the historical probability of fund investments obtaining follow-up financing - but this data will be distorted in later rounds (such as Round B) because project parties often choose to issue tokens rather than traditional equity financing.

Helping entrepreneurs identify active investors is just the first stage. The next step is to figure out which sources of capital are truly advantageous. Once we have this data, we can analyze which funds' co-investments will produce the best results. This is certainly not rocket science, just as no one can guarantee marriage on the first date, and no VC can guarantee a project's entry into the A round with just a check. But knowing the rules of the game in advance is just as important for fundraising as it is for dating.

1. Successful Architecture

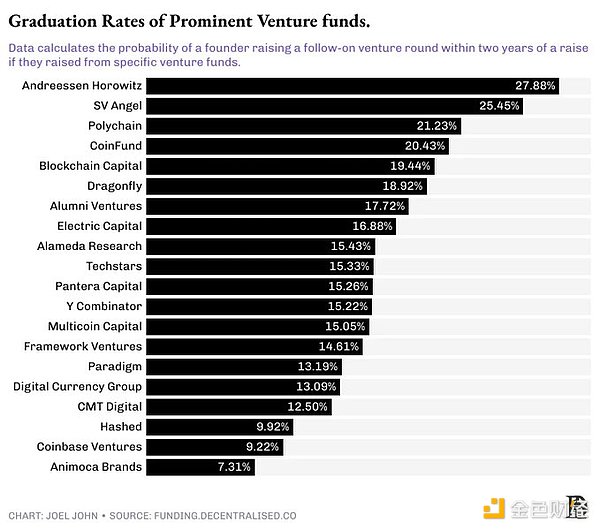

We use basic logic to screen out funds with the highest follow-up financing rate in the portfolio. If multiple projects invested by a fund can obtain new financing after the seed round, it means that its investment strategy is indeed unique. When the invested company completes the next round of financing at a higher valuation, the venture capital's book return will also increase, so the follow-up financing rate is a reliable indicator of fund performance.

We selected the 20 funds with the largest number of follow-up financings in their portfolios and counted their total investment cases at the seed stage. From this, we can calculate the probability percentage of entrepreneurs obtaining follow-up financing. For example, if a fund invests in 100 seed projects, and 30 of them obtain new financing within two years, its "graduation rate" is 30%.

It should be noted that we strictly limit the observation period to two years. Many start-ups may choose not to raise funds, or raise funds at a later stage.

Even among the top 20 funds, the power law effect is still amazing. For example, the probability of a16z-invested projects obtaining follow-up financing within two years is 1/3 - that is, one out of every three a16z-invested startups will enter the A round. Considering that the probability of the funds ranked at the bottom is only 1/16, this result is quite impressive.

Funds ranked near the 20th position on this list have a follow-up financing rate of about 7% of their portfolios. These numbers seem close, but to be specific: a 1/3 probability is equivalent to rolling a dice with a number less than 3, while a 1/14 probability is comparable to giving birth to twins - these are completely different results.

Jokes aside, the data truly reveals the clustering effect in the crypto venture capital sector. Some funds can proactively design follow-up financing for invested projects because they also operate growth funds. Such institutions participate in both seed rounds and follow-up A rounds. When venture capital continues to invest in the same project, it usually sends positive signals to investors in subsequent rounds. In other words, whether a venture capital institution has a growth fund will significantly affect the future success probability of the invested company.

The ultimate form of this model will be that crypto venture capital will gradually evolve into private equity investment in mature revenue-generating projects.

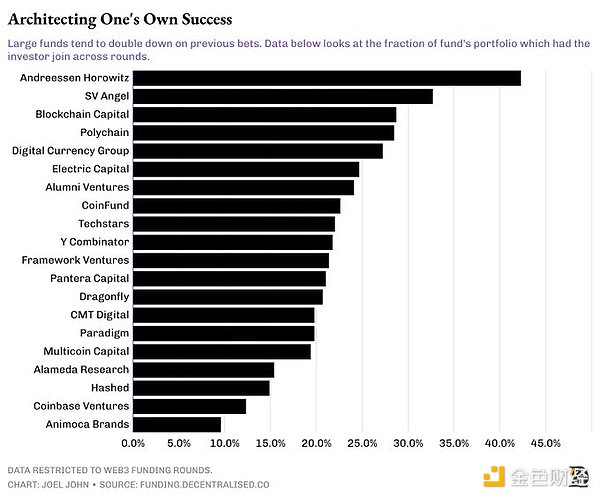

We’ve theorized about this shift. But what does the data reveal? To explore this question, we counted the number of startups in our portfolio that received follow-on funding and calculated the probability that the same VC firm participated in subsequent rounds.

In other words, if a company gets a seed round from a16z, what is the probability that a16z will participate in its Series A round?

The pattern soon emerged: large funds with a management scale of more than $1 billion tend to follow up frequently. For example, 44% of the projects in a16z's portfolio that received follow-up financing had continued investment by it; Blockchain Capital, DCG and Polychain would make additional investments in 25% of the projects that received follow-up investment.

This means that choosing investors in the seed or pre-seed rounds is far more important than imagined, because these institutions have a significant "preference for repeated investment".

2. Inertia joint investment

These rules are post-mortems. We are not suggesting that projects that are not favored by top venture capital are doomed to fail - the essence of all economic behavior is growth or profitability, and companies that achieve either goal will eventually be revalued. But if you can increase the probability of success, why not? If you cannot directly obtain investment from the top 20 funds, it is still a viable strategy to reach capital hubs through their networks.

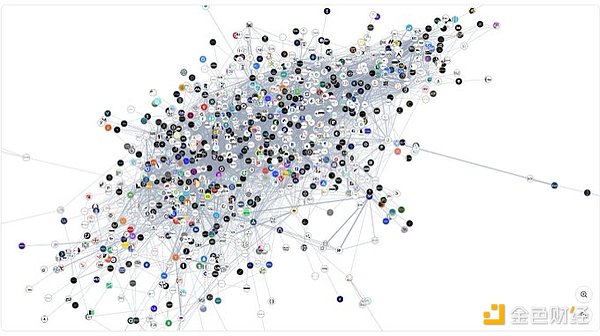

The following figure shows the network map of all venture capital institutions in the crypto field over the past decade: 1,000 investment institutions are connected through about 22,000 joint investments. On the surface, there seem to be many choices, but it should be noted that this includes funds that have ceased operations, have not achieved returns, or have suspended investments.

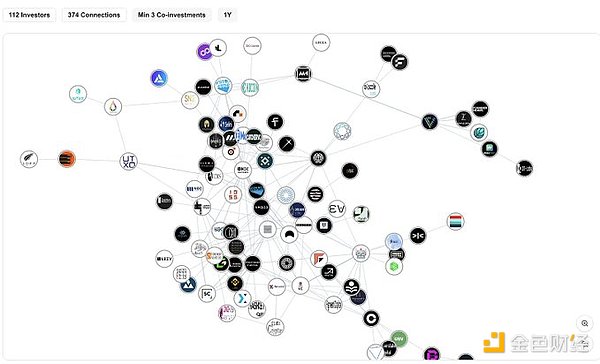

The real market structure is clearer in the figure below: there are only about 50 funds that can make a single A-round investment of more than US$2 million; the investment network participating in such rounds covers about 112 institutions; these funds are accelerating their integration, showing a strong preference for specific co-investment.

Funds seem to develop stable co-investment habits over time. That is, funds investing in one entity often attract peer funds due to complementary skills (such as technology assessment/market development) or based on partnerships. To study how these relationships work, we began exploring co-investment patterns between funds last year.

By analyzing the joint investment data of the past year, we can see that:

Polychain and Nomad Capital have co-invested 9 times;

Bankless and Robot Ventures have co-invested 9 times;

Binance, Polychain, and HackVC each co-invested 7 times;

OKX and Animoca have jointly invested 7 times.

Top funds are becoming increasingly strict in selecting co-investors:

Three of Paradigm’s 10 investments last year were made in partnership with Robot Ventures;

DragonFly co-invested with Robot Ventures and Founders Fund three times each among the 13 investments;

Three of Founders Fund’s nine investments were in partnership with Dragonfly.

This shows that the market is shifting towards "oligopoly investment" - a few funds are betting with larger chips, and most of the co-investors are old and well-known institutions.

3. Matrix analysis

Another way to study this is through the behavioral matrix of the most active investors. The figure above shows the network of funds with the highest investment frequency since 2020. It can be seen that accelerators are unique. Although accelerators such as Y Combinator invest frequently, they rarely invest in conjunction with exchanges or large funds.

On the other hand, you will find that exchanges also generally have specific preferences. For example, OKX Ventures and Animoca Brands have a high-frequency co-investment relationship, Coinbase Ventures has co-invested with Polychain more than 30 times, and has 24 co-investment records with Pantera.

The structural patterns we observed can be summarized into three points:

* Accelerators tend to rarely co-invest with exchanges or large funds, despite their high investment frequency. This may be due to stage preference.

* Large exchanges tend to have a strong preference for growth-stage venture funds. Currently, Pantera and Polychain dominate this.

*Exchanges tend to work with local institutions. The different preferences of OKX Ventures and Coinbase for co-investment targets highlight the global nature of capital allocation in the Web3 era.

Now that venture capital is converging, where will marginal capital come from? An interesting phenomenon is that corporate capital is self-contained: Goldman Sachs has only co-invested with PayPal Ventures and Kraken twice in history, while Coinbase Ventures has co-invested with Polychain 37 times, Pantera 32 times, and Electric Capital 24 times.

Unlike traditional venture capital, corporate capital usually targets growth-stage projects with product-market fit. At a time when early-stage financing is shrinking, the behavior of this type of capital is worth continuing to observe.

4. Dynamically evolving capital network

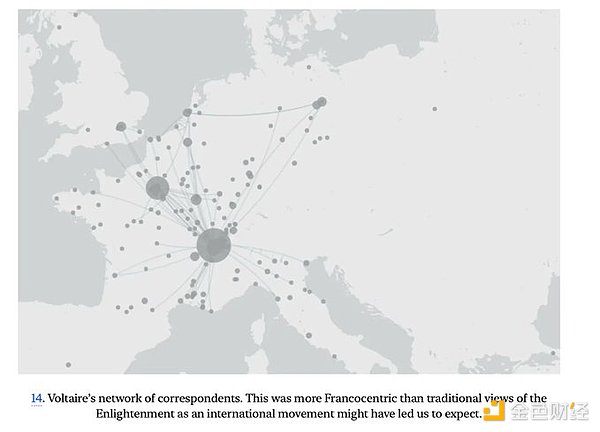

I first had the idea to study networks in crypto after reading Niall Ferguson’s The Square and the Tower a few years ago, which revealed that the spread of ideas, products, and even diseases is related to network structures, but it wasn’t until we developed our funding dashboard that we were able to visualize crypto capital networks.

This type of dataset can be used to design (and execute) M&A and token privatization plans - which is what we are exploring internally, as well as to assist in business partnership decisions. We are also looking into how to open up access to the data to select organizations.

Back to the core question: Can network relationships really improve fund performance? The answer is quite complicated.

The core competitiveness of a fund increasingly depends on the ability to select teams and the size of funds, rather than simply personal connections. However, the personal relationship between the general partner (GP) and the co-investor is indeed key - the shared project flow of venture capital is based on interpersonal trust rather than institutional brand. When a partner changes jobs, his or her network will naturally migrate to the new employer.

A 2024 study verified this hypothesis. The paper analyzed 38,000 rounds of investment data from 100 top VCs and came to the key conclusion:

*Historical collaboration does not guarantee future collaboration, and failed cases will disrupt trust between institutions.

*There is a surge in joint investments during the frenzy period, and funds rely more on social signals rather than due diligence during the bull market; there is a tendency to act alone in the bear market, and funds tend to invest independently when valuations are low.

*Principle of complementary capabilities: The gathering of homogeneous investors often indicates risks.

As mentioned above, ultimately, co-investing does not happen at the fund level, but at the partner level. In my own career, I have seen people jump between different organizations. The goal is usually to work with the same person regardless of what fund they join. In an era where artificial intelligence replaces human labor, interpersonal relationships remain the foundation of early-stage venture capital.

There are still many gaps in this research on crypto venture capital networks. For example, the liquidity allocation preferences of hedge funds, how growth-stage investments adapt to market cycles, and the intervention mechanisms of mergers and acquisitions and private equity. The answers may be hidden in the existing data, but it will take time to refine the right questions.