This article is from Compound, written by Knower and Smac

Release date: September 12, 2024

Original link: https://www.compound.vc/writing/depin

About 50,000 words | Reading time about 20 minutes

Editor's Note

Why is this research report worth reading?

- DePIN (Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Network) explores how to use decentralized technology to build and manage physical facilities in the real world, which may subvert many traditional industries . Understanding DePIN is crucial to grasping the future development of Web3.

- From macro to micro, this article systematically divides DePIN into six subcategories, covering core areas such as telecommunications, energy, computing power, decentralized AI, data and services, and outlines a complete ecological map for readers. In each field, there are real operating data of leading projects, revealing the project scale, user growth and business model.

- This article does not blindly promote the bright prospects of DePIN, but clearly points out the severe challenges currently faced by the DePIN project, especially the "imperfect status quo", such as the sustainability of the token economic model, the practical obstacles to competing with centralized giants, and the potential impact of future technologies (such as 6G, photonic computing, and distributed training). This balanced perspective helps readers evaluate the field more rationally.

In order to help you understand the key points of the article more quickly, we have summarized this research report.

In addition, DePINone Labs has fully translated and compiled it, and highlighted its key content to facilitate everyone's collection and sharing.

TL;DR

This report explores in depth the concept, current status, challenges and future of DePIN (Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Network).

DePIN aims to reshape the construction and management model of traditional physical infrastructure through blockchain and decentralized incentives, and achieve higher resource utilization, transparency and flexible ownership. The article points out that the real disruption lies in solving the pain points of the high-cost and low-efficiency centralized model , rather than simply "decentralizing".

The report divides the DePIN field into six subcategories:

- Telecom & Connectivity : From DeWi to fixed wireless and public WiFi, the focus is on analyzing the technical paths and market positioning of projects such as Helium, Karrier, Really, Andrena, Althea, Dabba, and WiCrypt.

- Energy : Distributed energy resources (DER), virtual power plants (VPP) and on-chain financing platforms, covering the business models and regulatory challenges of protocols such as Daylight, SCRFUL, Plural Energy, Glow, StarPower, Power Ledger, etc.

- Compute, Storage & Bandwidth : Explore the performance and differences of decentralized computing markets such as Akash, Fluence, IONet, Hyperbolic, Render, Livepeer, and storage networks such as Jackal, Arweave, and Filecoin.

- Decentralized AI : Lists projects such as Prime Intellect, Bittensor, Gensyn, Prodia, Ritual, Grass, etc., and analyzes the prospects of combining decentralized training, verification and data layers.

- Data Capture & Management : Emphasizes the market value and monetization challenges of content distribution, mapping, positioning and climate/weather data.

- Services : Showcase innovative use cases such as Dimo, PuffPaw, Heale, Silencio, Blackbird, Shaga, etc. that use crypto incentives to drive real-world behavior.

Although DePIN has shown great potential and is considered one of the most valuable long-term sustainable investments in the crypto space, it is still in its early stages of development and faces many "imperfect" real challenges, such as token economic model problems, real demand and adoption, supply and demand imbalances, competition and regulation, etc.

Despite the challenges, the report is optimistic about DePIN’s future (“a bright future”), believing that it has great long-term potential.

The key to future development lies in solving the sustainability problem of the token economy, truly focusing on solving meaningful real-world problems, and possibly finding breakthroughs in innovative areas such as environmental monitoring, biological data, and personal data sharing (such as bioacoustics, eDNA, and sleep/dream data mentioned in the report), pointing the way for subsequent innovation.

— — The following is the original research report — —

Gain insights into the emerging field of decentralized physical infrastructure.

By now, everyone in the crypto industry is familiar with the concept of Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks. They represent a potential paradigm shift in the way critical infrastructure is built, maintained, and monetized. At its core, DePIN leverages blockchain and decentralized networks to create, manage, and scale physical infrastructure without relying on any centralized entity. This approach ushers in a new era of open, transparent, community-driven growth and ownership, and aligns incentives for all participants.

While these ideals are important, for this type of decentralized network to reach their true potential, they need to build compelling products and solve meaningful problems. The real significance of DePIN is its potential to disrupt traditional models plagued by high costs and inefficiencies. We are all very familiar with centralized institutions that are slow to innovate and are often characterized by monopolistic or oligopolistic practices. DePIN can subvert this. The end result should be a more resilient and adaptable infrastructure that can respond quickly to changing needs and technological advances.

While we prefer not to construct market maps as this is often too backwards for the investment stage we undertake at Compound, in this case we found that much of the existing research overly complicated the state of this vertical. For us, at the highest level, we view DePIN through six different sub-categories (click on each to be taken to the corresponding section) :

- Telecom & Connectivity

- Energy

- Compute, Storage & Bandwidth

- Decentralized AI

- Data Capture & Management Data Capture & Management

- Services

One of the most common criticisms of cryptocurrencies is the cliché call for more “real-world use cases.”

Frankly, this is an old and ignorant argument, but it will likely persist regardless. Especially in the West — where people have long taken the use cases of cryptocurrency for granted — we will all benefit from more understandable use cases that demonstrate the potential of this technology. In this regard, DePIN demonstrates unique value — it is the best example of crypto incentives creating real-world utility, enabling individuals to build and participate in physical networks that were previously impossible. Most current crypto projects rely entirely on software success, while DePIN emphasizes tangible hardware facilities in the physical world. Narratives and storytelling are an important part of every technological wave, and whether we like it or not, the entire crypto industry needs to tell the story of DePIN in a more effective way.

Despite a few industry leaders (such as Helium, Hivemapper, and Livepeer), there are still many unsolved problems as DePIN matures. Its core value proposition is to disrupt the traditional infrastructure provision and management model. By implementing crypto incentives, DePIN can achieve:

- Higher resource utilization

- Greater transparency

- Democratizing infrastructure construction and ownership

- Fewer single points of failure

- Higher efficiency

All of this would, in theory, lead to a more resilient real-world infrastructure.

We believe that another core value proposition of DePIN is its ability to completely subvert existing business models through cryptoeconomic models. Although there will always be people who look at certain DePIN projects with suspicion and cynically view them as businesses with weak business models that require artificial token incentives. However, this report will highlight that in some cases, the introduction of blockchain will actually greatly improve the existing model, or in some cases introduce a completely new model.

While we have our own opinions on this, we mostly ignore that where to build these networks in the long run remains an open question: Solana has become the focal point of the DePIN ecosystem, but no matter what underlying protocol is chosen, there will inevitably be trade-offs.

Like all network types, the development of DePIN needs to focus on two core dimensions: demand side and supply side . It can be said that the verification difficulty on the demand side is (almost) always higher. The most intuitive explanation for this is that the token incentive model is naturally easier to map to the supply side. If you already have a car or idle GPU computing power, there is almost no additional cost to install a dash cam or provide idle computing resources. There is almost no friction in this regard.

But when it comes to demand, the product or platform must provide real value to paying users. Otherwise, demand will never form or become speculative capital. To give some practical examples, the demand side of Helium Mobile is users seeking better cellular network tariff plans. The supply side of Hivemapper is individual contributors who provide high-precision map data to earn tokens. Importantly, both cases are easy to understand.

When discussing supply and demand, we must delve into the core element that supports all DePIN activities: the token incentive mechanism .

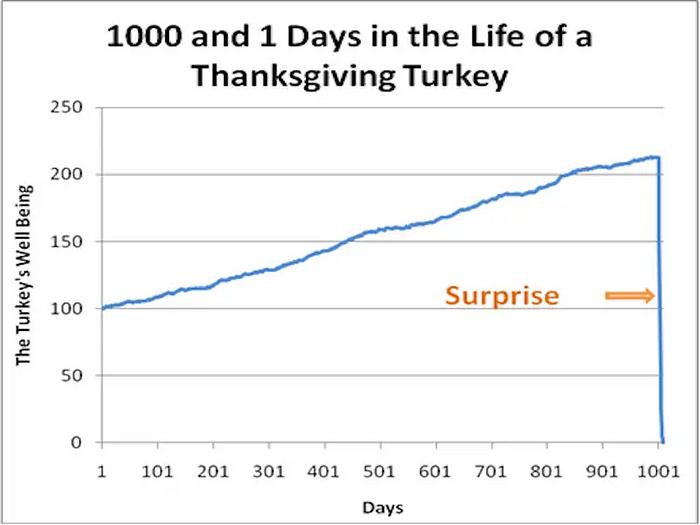

You can’t discuss supply and demand without expanding on the core part that underpins all of these DePIN activities: token incentives. In a report this summer, 1kx analyzed the cost structures of multiple DePIN projects in detail and assessed the sustainability of these systems. The key conclusion is that it is difficult to match reward distribution with operating costs and demand growth, let alone build a universal model for each DePIN project. Generalizing doesn’t work, especially in verticals that are so diverse that involve real-world economies. The complexity of the markets that these networks are trying to reshape makes them both exciting and challenging.

While there are some differences between project models, in most cases the cost structure of DePIN projects comes from: a) determining the cost of participation for node operators; b) determining the operating efficiency of network nodes; and c) examining differences between project accounting mechanisms.

This report is definitely worth a read, but there is one important takeaway: you can’t generalize token economics, nor make assumptions about one project based on another project’s failure to properly maintain token incentives. More importantly, the entire DePIN space cannot be dismissed based on token economics alone. From the perspective of DeFi in particular, there is still no sustainable token economic model that can both reward new users and continue to incentivize existing funds. The reduced capital expenditure (CapEx) brought by the traditional DePIN model not only makes network launch and business operations more convenient, but also gives it a competitive advantage over the traditional model in terms of system construction methods (we will explore this in depth in the full text).

We believe that a key point that is often overlooked is the true meaning of network effects .

We often refer to these systems as networks, and sometimes even confuse them with the principle of network effects. Ideally, the DePIN network will start on one side (usually the supply side), then the demand side will start to grow, which will attract more supply-side resources to join, forming a virtuous cycle of exponential value expansion. However, the existence of a two-sided market alone does not mean that there is a network effect.

So, do existing businesses have certain attributes that make DePIN an attractive disruption model? We believe that the DePIN model will demonstrate unique advantages when at least one of the following conditions is met:

- Expansion of infrastructure with a single vendor is costly or cumbersome

- Opportunities exist to improve the efficiency of matching supply and demand

- Ability to accelerate the achievement of a lower cost end state by revitalizing idle assets

To make the report easier to understand, we will divide it into the six categories mentioned above. Each section will cover the core concept or problem, the solution of the existing team, and our views on the durability of the industry and the problems that remain to be solved. If you want to get a direct glimpse into our internal thinking, the last section of the report explores some DePIN innovation ideas that we are looking forward to collaborating on.

Telecom & Connectivity

The modern telecommunications industry developed primarily in the 1990s, when wired technology was rapidly replaced by wireless technology. Cell phones, wireless computer networks, and wireless Internet were just beginning to make their way into the wider retail sector. Today, the telecommunications industry is large and complex, managing everything from satellites to cable distribution, wireless carriers to sensitive communications infrastructure.

Everyone is familiar with some of the largest companies in the space: AT&T, China Mobile, Comcast, Deutsche Telekom, and Verizon. To put the scale into perspective, the traditional wireless industry generates more than $1.5 trillion in annual global revenue in three main areas: mobile, fixed broadband, and WiFi. Let’s quickly differentiate between these three areas:

- The mobile communications industry creates and maintains connections between people; every time you make a phone call, you are using mobile infrastructure.

- The fixed broadband industry refers to high-speed internet services provided to homes and businesses over a fixed connection (usually via cable, fiber, DSL or satellite), offering more stable, faster and, in some cases, unlimited data connections.

The WiFi industry manages the most widely used connection protocols that enable everyone to access the internet and communicate with each other.

About two years ago, the EV3 team shared a post detailing the state of existing telecom companies.

“With $265 billion worth of productive physical assets (radio equipment, base stations, towers, etc.), telecom companies generate $315 billion in service revenues per year. In other words, a productive asset turnover rate of 1.2x. Pretty good!”

But these companies require hundreds of thousands of employees and billions of dollars worth of resources to continue to manage this growing infrastructure. We encourage you to read this post in its entirety as it further explores how these companies pay taxes, update infrastructure, manage licenses, and ultimately stay operational. This is an unmanageable and unsustainable model.

Recently, Citrini Research revealed some of the looming problems facing the incumbent telecom giants. They detailed the financials of many of these companies and painted a worrying picture: overly optimistic forecasts (attributed to the pandemic) have left many with large backlogs of inventory that are difficult to deploy. Specifically, this includes large backlogs of fiber optic cables on balance sheets following the fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) personal connection boom. The problem is that there is nowhere to absorb this inventory. Citrini further noted that demand has shifted from personal connections to " shared campus and metro networks to deploy inventory and support the new technology boom" for extended access.

Telcos will not be able to roll out new supply quickly enough, and demand growth has reached a point where it is difficult to keep pace - DePIN can fill this supply gap. This creates a unique opportunity for decentralized wireless projects to both scale network growth faster than incumbent operators, while meeting the growing demand for wired and wireless infrastructure at the same time. Citrini specifically points to the need for fiber networks and WiFi hotspots, and while decentralized deployment of fiber nodes has not been explored in depth, the implementation of WiFi hotspots is feasible today and is already underway.

We mentioned the three pillars of wireless technology earlier, let’s now take a closer look at each of them and compare their decentralized models to the existing telecommunications industry today.

Mobile Wireless

Mobile wireless is probably the best-known sub-sector of decentralized wireless (DeWi), which in this context refers to decentralized networks that provide cellular connectivity (i.e. 4G and 5G) through a distributed network of nodes. Today, the traditional mobile wireless industry relies on a network of cell towers that provide coverage to a specific geographic area. Each tower uses radio frequencies to communicate with mobile devices and connects to the broader network via backhaul infrastructure (i.e. fiber). The core network handles all switching, routing, and data services — a centralized provider connects the cell towers to the internet and other networks.

We know that infrastructure construction is capital intensive, and deploying 5G requires a denser network, especially in urban areas, which requires more towers. Rural and remote areas often lack coverage because of the smaller number of potential users and lower return on investment, making it a challenge to expand coverage to these areas.

While the actual construction of the infrastructure is expensive, this also brings with it the need for ongoing maintenance. In addition to repairs, software updates, and upgrades to support new technologies (such as 5G), network congestion issues in high-density areas may degrade service quality, requiring more ongoing investment in network optimization and capacity upgrades. This is a problem that these operators should have foreseen long ago, by the way.

While the actual construction of the infrastructure is expensive, this also brings with it the need for ongoing maintenance. In addition to repairs, software updates, and upgrades to support new technologies (such as 5G), network congestion issues in high-density areas may degrade service quality, requiring more ongoing investment in network optimization and capacity upgrades. This is a problem that these operators should have foreseen long ago, by the way.

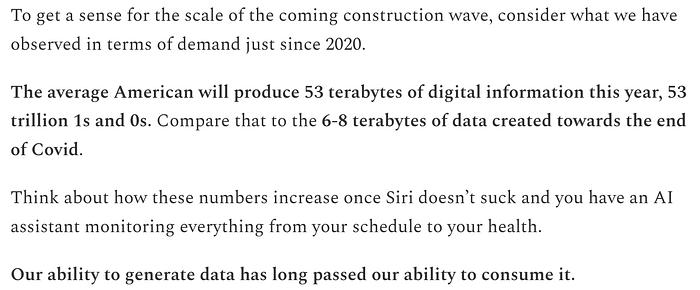

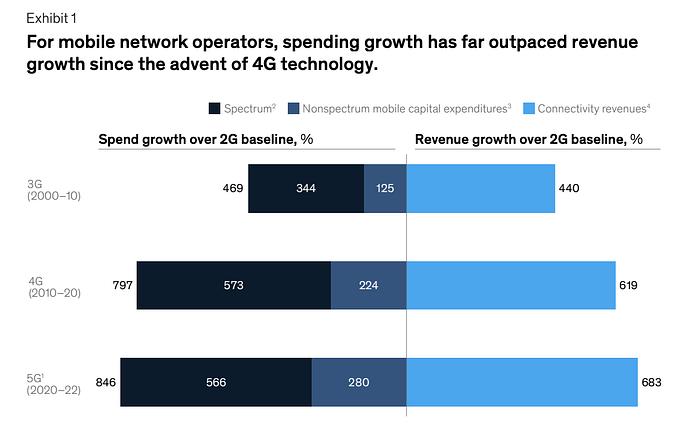

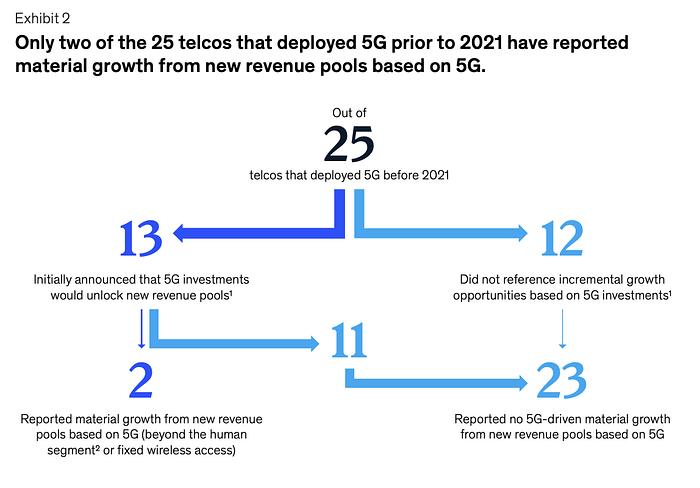

The promise of a data-driven market and unlimited growth potential drove spectrum costs from $25–30 billion in the 2G era to $100 billion in the 3G era. Capital costs rose to enhance core infrastructure and expand mobile networks to cover more than half of the world’s population by 2010. Despite the rapid growth in subscribers brought about by 3G, rising costs began to outpace revenue growth. While the BlackBerry was the iconic device of the 3G era, the iPhone was clearly the device that shaped and dominated 4G.

These two technologies (4G and the iPhone) brought the Internet to handheld devices, and data usage grew vertically from an average of less than 50 megabytes (MB) per phone per month in 2010 to 4 gigabytes (GB) by the end of the 4G era. The problem was that while data revenues grew, they were not nearly enough to offset the sharp decline in traditional voice service and SMS revenues (which fell by about 35% per year between 2010–2015 alone). In addition, operators had to spend more than $1.6 trillion on spectrum, core network upgrades, and infrastructure expansion to meet the insatiable demand for network capacity and coverage.

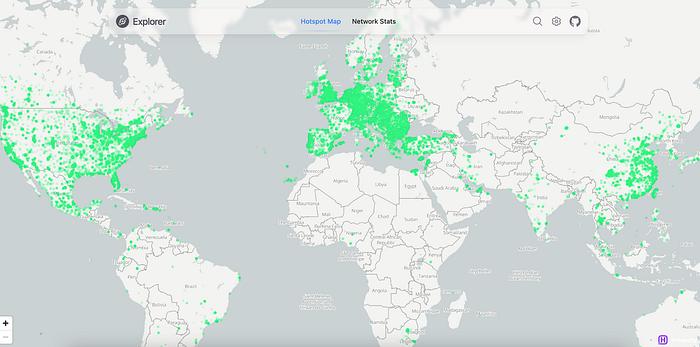

The decentralized wireless space is most often associated with Helium. And rightfully so, in our opinion. Helium was founded over a decade ago with the original vision of creating a decentralized wireless network for the Internet of Things (IoT). The goal was to build a global network that would allow low-power devices to connect wirelessly to the internet, enabling a wide range of applications. While the network was growing, the IoT market itself was showing limitations in terms of scale and economic potential. In response, Helium expanded into mobile telecommunications, leveraging its existing infrastructure while targeting more lucrative and data-intensive markets. Ultimately, Helium announced Helium Mobile, a new initiative designed to build a decentralized mobile network — an initiative that clearly aligns with Helium’s broader vision of creating a decentralized wireless ecosystem. Today, Helium has over 1 million hotspots in its coverage network and over 108,000 users on its mobile network.

Helium's IoT platform is focused on connecting low-power, low-range devices to support niche networks such as smart cities or environmental monitoring. The platform is powered by the LoRaWAN (Low Power Wide Area Network) protocol and is designed to connect these battery-powered devices to the Internet in regional, national or global networks. The LoRaWAN standard is generally targeted at two-way communication, allowing two or more parties to communicate in both directions (send and receive).

IoT networks consist of devices such as vehicles and appliances that are connected within the network through sensors and software that enables them to communicate, manage, and store data. Helium's IoT platform was formed around the idea that the world's applications will require widespread coverage and low data rates. While individuals can spin up a hotspot at relatively low cost anywhere in the world, most appliances only need to send data occasionally, making the cost of running traditional infrastructure capital inefficient.

By combining LoRaWAN with a decentralized network built by Helium, it is now possible to reduce capital expenditures and expand the coverage of the network. Helium has approved over 16 different types of hotspots for operation, each of which is quite affordable.

Helium Mobile was created as an alternative to traditional wireless providers. Initially, the team created a decentralized mobile network that could coexist with traditional cellular networks, introducing a mobile virtual network operator (MVNO) model where Helium could provide seamless coverage by partnering with existing operators while leveraging their networks to provide additional capacity and lower costs. This hybrid approach allows Helium to offer competitive mobile services while expanding its decentralized network. Helium Mobile is compatible with existing 5G infrastructure, providing a low-cost platform for smartphones, tablets, and other mobile devices that require high-speed connectivity.

Verizon and AT&T each have over 110 million subscribers, with average monthly plans of $60–90 for individuals and $100–160 for families. In contrast, Helium Mobile offers unlimited plans for $20/month. How is this possible?

This is thanks to one of the core benefits of DePIN (Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Network) - significantly reduced capital expenditures. Traditional telecom companies need to build all the infrastructure themselves and carry out ongoing maintenance. In turn, these operators pass part of the costs on to customers in the form of higher monthly fees. By introducing token incentives, teams like Helium can solve the launch problem while passing on capital expenditures to its network of hotspot managers.

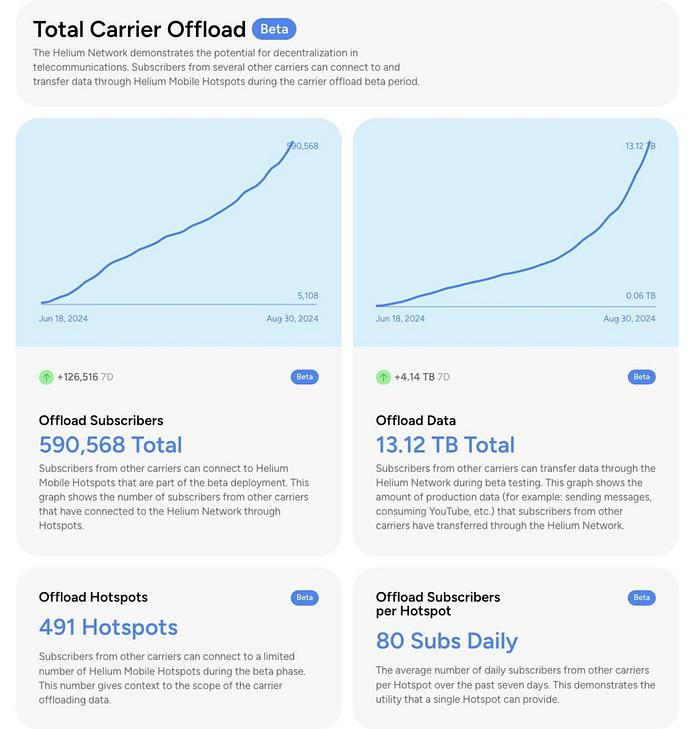

One point we made in the introduction to this report is that ultimately these DePIN teams need to deliver products and services that have real demand. In the case of Helium, we are seeing them make meaningful progress with the world’s largest mobile operators. The recent partnership with Telefonica extends Telefonica’s coverage and allows for mobile data offload to the Helium network.

Specific to offload, some back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that there could be significant revenue from mobile offload alone. Assuming mobile users consume ~17 Gigabytes of data per month, and Helium’s carrier offload service picks up ~5% of data usage from large carriers, this would result in over $50 million in revenue. There are obviously a lot of assumptions here, but we are in the early stages of these agreements, and these revenues could increase significantly if customer conversion or offload rates are higher.

Helium is a great example of the power of decentralized networks at scale. A project like this would have been impossible a decade ago. Back then, Bitcoin was so niche that it was hard to get people to build Bitcoin mining rigs at home, let alone build buzz for a very new industry in the crypto space. Helium's current and future success is a net positive for the entire space, provided they can gain market traction relative to their traditional competitors.

Next, Helium will focus on expanding coverage, with the unique ability to target growth in areas where it most frequently sees coverage switches to T-Mobile. This is another subtle benefit of the token model — as Helium gathers data on the areas where coverage outages are most common, it can offer incentives to those closest to those areas, quickly targeting high-density but uncovered areas.

There are other companies in the DePIN mobility space that are developing their own innovative solutions: Karrier One and Really are two examples.

Karrier One claims to be the world’s first carrier-grade, decentralized 5G network that combines traditional telecom infrastructure with blockchain technology. Karrier’s approach is very similar to Helium, where individuals in the network can set up nodes — cellular radios similar to Blinq Network’s PC-400 and PC-400i (which run on Sui).

Karrier's hardware is very similar to Helium's, but their software and GTM (go-to-market strategy) are different. Helium wants to cover as much of the world as possible, while Karrier is initially focusing on underserved or remote areas. Their software is able to send and receive payments using a phone number connected to a mobile device's SIM card, bypassing the banking system.

In their own words, Karrier is able to create “a virtual phone number for all your web3 notifications, payments, logins, permissions, and more,” called KarrierKNS. This makes Karrier potentially more suitable for communities or regions without a robust banking infrastructure, while Helium may be more suitable for individuals in more developed areas who want to reduce the cost of their cell phone plans.

Karrier's network architecture consists of base nodes, gateway nodes, and operation nodes. Base nodes manage authentication and blockchain maintenance, gateway nodes handle wireless access for end users, and operation nodes provide traditional telecommunications modules. All of this runs on Sui smart contracts, with the Karrier One DAO (KONE DAO) managing the internal review process. Their use of blockchain technology revolves around the following principles:

- Smart contracts are superior to authority and bureaucracy

- Blockchain gives users power and privacy over their data while maintaining transparency

- The token economics of the Karrier One network paves the way for shared success among network participants

Karrier is clearly in its infancy compared to Helium, but there could be more than one DeWi protocol that succeeds. Exactly how many remains to be seen, although we often see MVNOs (Mobile Virtual Network Operators) in the traditional telecom market changing hands at valuations in the billion dollar range. The telecom industry is also clearly somewhat oligopolistic, with Verizon and AT&T. Where Karrier could succeed is in banking the unbanked through its KarrierKNS initiative, while Helium gradually eats into traditional telecom market share. A relevant note here is Karrier’s emphasis on the future adaptability of its network to accommodate 5G, edge computing and further technological advances. What this means in practical technical capabilities is beyond the scope of this report, but suffice it to say that this is an interesting positioning at a time when the traditional telecom industry is cautious about investing in 6G.

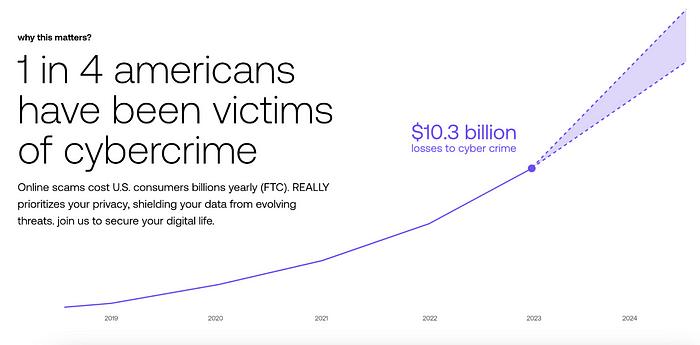

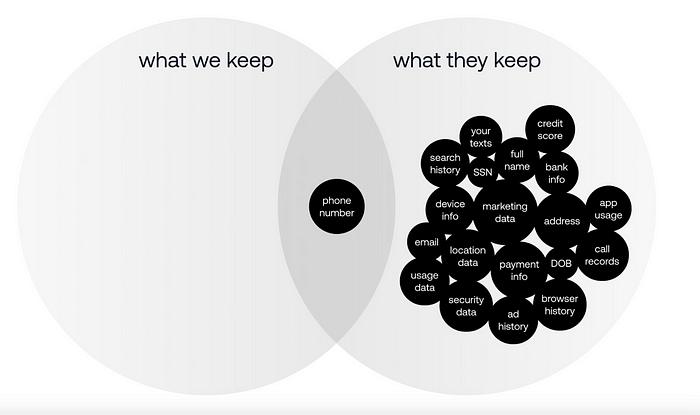

Really is the world's first fully encrypted privacy wireless operator, where users participate in network construction by deploying small cellular radio devices around the world. The core of the project is to ensure the privacy of all network transmission data - traditional mobile phone package users do not really own their data, which makes Really a pioneer in user-first telecommunications projects.

Data provided by Really shows that 1 in 4 Americans has been victimized by cybercrime. The scale of user data leakage is staggering, and this problem will only get worse over time. With the popularity of IoT devices such as smart refrigerators, smart cars, smart door locks, and home robots, the cyber attack surface is expanding dramatically.

Besides that, anonymity is rarely possible on the modern internet. It is becoming increasingly difficult to sign up for a new account anywhere without revealing personal information. Most companies are known for hoarding large amounts of user data, and this data collection is only going to increase thanks to the development of artificial intelligence.

Traditional telecommunications require large cell towers, which naturally lead to geographic gaps in coverage. Really fills this gap by deploying an infrastructure of these small “cells” in the homes of network participants.

Their mobile plans offer customers complete identity protection and monitoring services, including a self-developed security suite (anti-worm, anti-ransomware), as well as SIM swap protection and insurance services. Really first aims to provide customers with protective customized mobile plans. Currently, its unlimited plan costs $129 per month, including unlimited data, calls and texts, unlimited calls to 175+ countries, full encryption, and VIP services through the Really VIP program. This draws on a business model similar to private medical services, as more and more consumers seek customized services that traditional providers cannot provide.

This approach to the DePIN mobile space is truly unique in that it differentiates itself through functionality and privacy rather than cost. It’s obviously too early to extrapolate too much, but as a general idea – building differentiation based on core ideas that are not yet widely accepted (in this case, the importance of privacy and encryption) is one way to carve out space in a competitive market.

It’s easy to argue that mobile wireless is the most promising area in DePIN. Smartphones are ubiquitous. The industry also benefits from lower switching costs thanks to the advent of eSIM, which no longer requires a physical SIM card. This allows users to store services from multiple operators on a single eSIM, making it more convenient for frequent travelers. This should continue. Assuming it continues, the case for mobile DePIN to take advantage of and potentially achieve new breakthroughs through advances in eSIM technology becomes even stronger.

While smartphones and other mobile devices are powerful sensing endpoints, they also present a unique set of challenges:

- Continuous data collection raises privacy concerns and device battery drain

- Data voluntarily provided by users usually has a low retention rate

- Data mining can attract certain users and lead to unintended biases in datasets

- Airdrop speculators make it difficult to distinguish between real users and fake traffic

- Defensiveness is prone to vicious competition for token rewards

These issues are not unsolvable. First, an “opt-out” feature or the option to delete data entirely may attract users who are skeptical of data collection. Simply providing an opt-out option is a strong trust signal in itself. We have also seen large-scale crackdowns on airdrop speculators, with LayerZero being the most obvious public example.

It is worth noting that mobile wireless communications have the highest revenue per GB in the telecommunications industry. Mobile devices require constant connectivity, which gives operators greater pricing power than fixed broadband or WiFi. In addition, continued improvements in connectivity standards such as 5G, which bring faster speeds and higher performance, further strengthen this pricing advantage.

So what comes after 5G? That’s right… 6G.

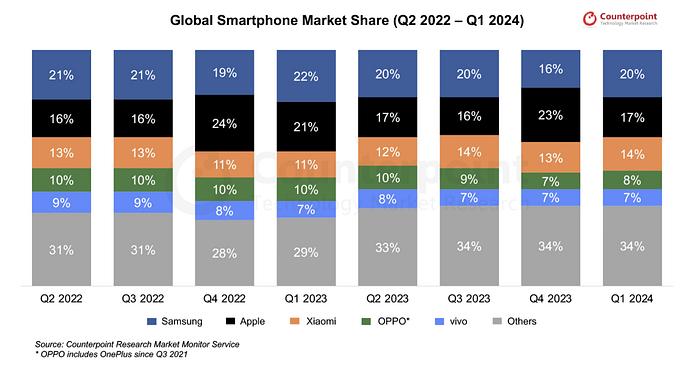

6G promises to enable instant communication between existing smart devices and support the popularization of a new generation of wearable devices. Although it is too early to discuss it, it is essentially an upgraded version of 5G with stronger performance. Interestingly, one of the key issues facing 6G is how to coordinate existing stakeholders to reach a consensus. Currently, telecom equipment manufacturers, governments, mobile operators, semiconductor manufacturers and equipment manufacturers lack a unified understanding of the goals, characteristics and requirements of 6G. The figure below (although complex) shows that the only thing that all parties agree on is: there is a general skepticism about how 6G can create value on existing infrastructure.

Understanding where these stakeholders diverge, and which groups are most likely to “win” in disputes, is critical to understanding how the industry evolves. This is why we think DePIN is particularly attractive — we see veteran practitioners from other tech industries bringing their expertise to this space to solve problems. While it takes more work to delve into these dynamics, the rewards for winning in this huge market will be staggering.

Fixed Wireless

As the name implies, fixed wireless refers to high-speed Internet service provided via a fixed connection, usually using cable, fiber optic, DSL or satellite technology. Compared with mobile networks, fixed broadband can provide more stable and faster data connections. It can be divided into:

Fiber optics

- Transmitting optical signals through glass or plastic fibers

- Provides ultra-low latency connections over 1Gbps

- Best for online gaming, video conferencing and cloud applications

- The gold standard for fixed broadband, the most future-proof

- Costly to lay in sparsely populated areas

Cable s

- Uses coaxial cable (originally laid for television) to provide Internet access

- Modern systems usually use a hybrid solution combining optical fiber backbone network and coaxial cable

- Theoretical speed can reach 1Gbps, but actual performance will be affected by peak hours

- The latency is lower than that of fiber, but the performance degrades at high traffic

- With the development of DOCSIS 4.0 technology, the theoretical speed of cable can reach 10Gbps, which is close to the performance of optical fiber.

DSL

- Delivering Internet over traditional copper telephone wires

- One of the oldest forms of broadband

- Speeds are typically 5–100Mbps with high latency

- Gradually eliminated

Satellite s

- Internet access via Earth-orbiting satellites

- Traditionally, high-orbit geosynchronous satellites have been used, but emerging low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellites are changing this field.

- LEO speed 50–250Mbps, latency 20–40ms

- Geosynchronous satellites have high latency due to long transmission distances, and LEO significantly improves this problem.

- Global coverage

- Great growth potential in areas lacking ground infrastructure

- It mainly plays a supplementary role in suburban areas where optical fiber and cables are already available.

Fixed broadband currently has higher user stickiness and retention rates due to the difficulty of switching providers (such as installation costs and downtime) and inherent package bundling (such as cable broadband).

On the surface, this is an optimistic outlook, but it contains several questionable assumptions. The most tangible high-impact threat comes from 5G and future 6G technologies – which offer multi-gigabit speeds and low latency comparable to fiber broadband, but with the added advantages of mobility and ease of deployment. It is likely that there will be a large-scale abandonment of fixed services, especially in suburban areas.

Another potential threat (although more long-term) is LEO satellite broadband systems. Although Starlink and Project Kuiper are currently expensive and lack performance, they will become a strong challenger to fixed broadband in the long run as data caps are lifted and costs fall.

Ignoring these two threats could put players in this space at risk of losing subscribers (particularly fiber, cable, and DSL broadband providers).

Fixed internet revenue per GB is only one-tenth of mobile wireless, so how do these companies make money? The core business model comes from monthly packages, tiered services, and customized plans for different businesses. They can charge businesses for customized solutions (such as hedge funds competing for better underground cable locations), provide faster speeds at a high price, and bundle services (cable TV, Internet, and phone). Major providers in the United States include Comcast (Xfinity), Charter Communications (Spectrum), AT&T, Verizon, and CenturyLink, and internationally there are Vodafone, British Telecom, and Deutsche Telekom. Although Comcast and Charter currently dominate the US fixed broadband market, fiber providers such as AT&T and Verizon are quickly gaining share by actively laying fiber to the home (FTTH).

Fixed Internet uses point-to-multipoint (PtMP) technology, where a single central node (base station) connects multiple end nodes (users) through a shared communication medium. In fixed wireless, this means that the central antenna sends signals to multiple receivers. The main challenge of early PtMP was signal attenuation and performance degradation caused by interference from co-band devices. Another obstacle was that the shared nature of the PtMP architecture resulted in limited bandwidth and reduced speed when more users were added.

Today, PtMP systems are becoming more efficient by adopting more advanced modulation schemes (OFDM, MIMO) and higher frequency bands (mmWave), enabling greater bandwidth to support more users. However, mmWave signals are still susceptible to attenuation—rain, foliage, and physical obstacles can significantly degrade performance. The fixed Internet space is still evolving, providing space for new DePIN players to enter with unique solutions.

Andrena and Althea are two of the more well-known companies in the DePIN fixed wireless space. Andrena provides high-speed networks to multi-family residences (MDUs) at competitive prices, and its unique market strategy is to minimize customer installation requirements. As mentioned earlier, fixed Internet users are more sticky due to switching costs and the difficulty of migrating physical infrastructure.

Andrena uses fixed wireless access (FWA) technology to provide broadband services through wireless signals rather than cables. FWA deployment costs are much lower than wired broadband and can be expanded faster, but it is more susceptible to interference, environmental impacts and performance fluctuations. The company deploys antennas on rooftops to cover a wide area - high-density places such as apartment buildings and office buildings. The basic package costs $25/month for 100Mbps and $40/month for 200Mbps, which is about 30% cheaper than Verizon or AT&T on average. By establishing a revenue-sharing cooperation model with real estate companies and property owners to accelerate antenna deployment, property owners can provide high-speed networks as value-added services to residents and obtain revenue sharing. Andrena initially focused on markets such as New York, Florida, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Connecticut.

Andrena recently announced the launch of Dawn, a decentralized protocol. Previously, the company operated like a traditional enterprise, but only promoted the concept of decentralization. Dawn connects buyers and sellers of network services through a Chrome extension, theoretically allowing individuals to become their own network providers. The key question is how value will accumulate - will it flow to entities such as laboratories, or will it actually return to tokens?

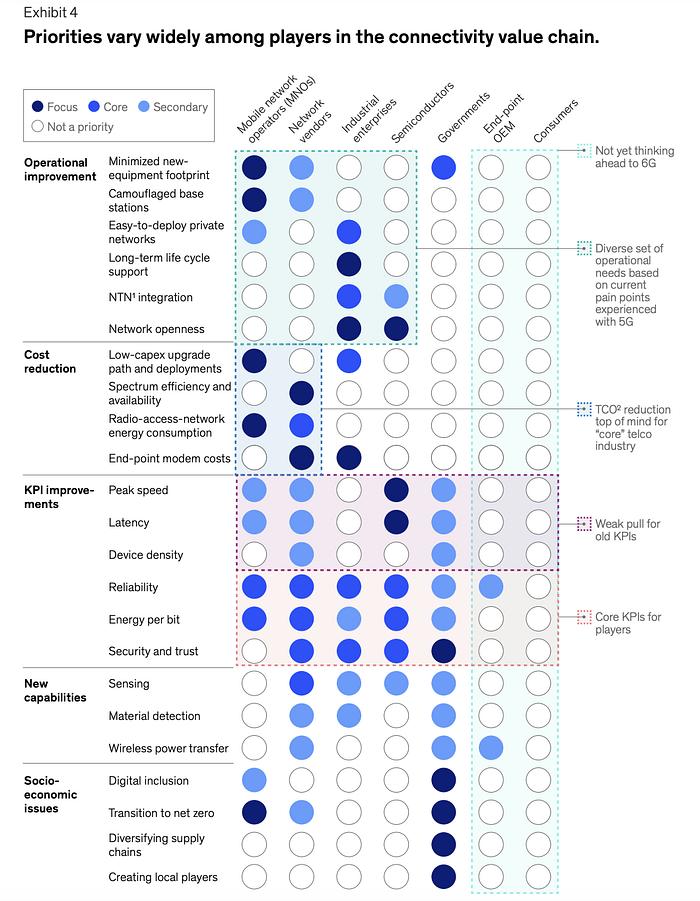

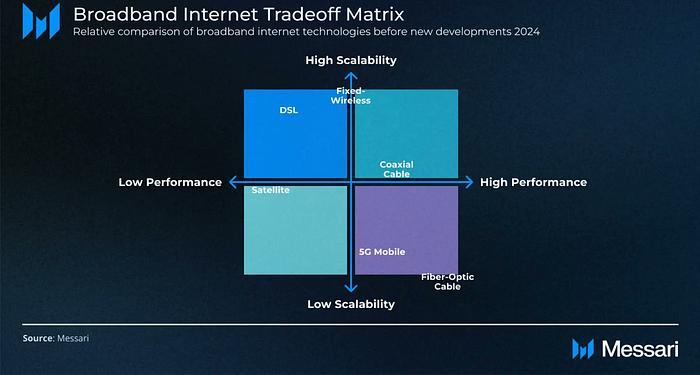

In an in-depth report, Messari’s Dylan Bane points out that the broadband sector faces a trade-off similar to the blockchain trilemma — except that the broadband trilemma is about how the service is delivered. Technologies such as coaxial cable, fiber, DSL, and satellite each fall into different quadrants such as “best performance but worst scalability” or “worst security but best performance.”

It is important to note that this reflects the current static situation, while we are more concerned about future development trends. What is important is not the current position of these technologies, but their potential to develop to the upper right corner of the matrix. This will determine the strategy and success or failure of startups.

It is important to point out that the view that fiber is at the bottom of the scalability spectrum is biased. Although the cost of laying fiber is high, fiber deployment has been completed in densely populated areas. Although it is difficult to expand to new areas, fiber has firmly occupied the suburban market.

The core idea of the Dawn project is that recent advances in wireless technology have enabled companies to compete with fiber providers at lower costs. Its white paper points out that multi-gigabit capacity, mechanical beamforming, and high-frequency unlicensed spectrum are key technological breakthroughs, and defines the Dawn protocol as:

Directly connect users to Internet exchange nodes without trusted intermediaries

Minimize the hundred-fold price difference between wholesale and retail networks

Eliminate reliance on a single network path by consolidating home nodes

The Dawn network consists of bandwidth nodes, distribution nodes, and end users, and achieves trustless bandwidth demand matching through protocols. Its goal is to build a device network while maintaining supplier neutrality. Most DePIN projects face challenges such as high-quality supplier screening, user external platform jumps, and hardware home deployment. Dawn chooses to prioritize 60GHz millimeter wave and 6GHz frequency band technologies because of their short-range communication characteristics and high-bandwidth transmission capabilities.

The project chose Solana blockchain to manage service contracts, which are used to record service agreements between network nodes and end users. The protocol will introduce three mechanisms: proof of bandwidth (PoB), proof of service (PoS), and proof of location (PoL) to coordinate transactions among participants. Although proof of bandwidth is not the first, Dawn aims to achieve sustainable operation of large-scale home ISPs through token economy. The proof of location mechanism (described in detail later) serves as a digital certificate of user identity and real-time location.

The Dawn system introduces a new mechanism called "medallions", which is essentially a staking unit of account that earns holders 12% of the revenue on high-value regional chains. These medals serve as a gateway to the Dawn network - assuming decentralized broadband services take off and eventually disrupt traditional operators, the 12% revenue share that medal holders receive will be extremely substantial.

With the existing customer base of Andrena, Dawn's initial deployment will cover more than 3 million households and is expected to generate more than $1 million in annual recurring revenue (ARR). The system is designed so that early participants can share in the continuous benefits of network expansion by staking medals.

Althea

Althea is positioned slightly differently, positioning itself as a payment layer that supports infrastructure and network connectivity. It is a Layer 1 blockchain that provides dedicated block space for subsequent Layer 2 networks, supports machine-to-machine (M2M) micropayment services, and guarantees revenue through contracts while maintaining compatibility in hardware development. It sounds a bit complicated... What does this mean? What does it have to do with fixed wireless networks?

In fact, Althea is a protocol that allows anyone to install equipment, participate in the operation of a decentralized Internet Service Provider (ISP), and earn tokens for it. Its core idea is to allow users to buy and sell bandwidth directly between each other, bypassing the middlemen of traditional fixed network service providers. Althea achieves this goal through specialized intermediate nodes that connect decentralized networks directly to the wider Internet through Internet exchange points (IXPs) or commercial-grade connections of traditional ISPs.

So, what is an Internet Exchange Point (IXP)?

An IXP is a physical infrastructure that enables multiple ISPs to interconnect and exchange traffic directly. Instead of routing traffic through a third-party network, participants in an IXP can exchange traffic directly, reducing costs. The core principle of an IXP is to facilitate "peering" agreements between networks:

- Public Peering : This is achieved through the shared infrastructure of an IXP, where multiple networks connect to a common exchange, allowing extensive exchange of traffic between a large number of participants.

- Private Peering : A direct, dedicated link between two networks that occurs within the same data center or IXP facility, typically used for high-volume traffic exchange between two specific networks.

Due to the direct connection between networks, IXPs can generally provide lower latency and higher speeds than traditional ISP routing. Reducing the number of intermediate hops means that data packets can reach their destination faster. Most ordinary consumers still get network services through ISPs rather than directly from IXPs, mainly due to issues such as "last mile" connection, user device compatibility and network architecture design.

One of the advantages of DePIN is that it can reduce costs in the early stages of project operations and maintain this principle throughout the project life cycle. In Althea's system, nodes can dynamically adjust costs based on verifiable supply and demand, making it a real price discovery mechanism in the fixed Internet service market.

Althea allows participants to tokenize funds and infrastructure on the chain, calling it "Liquid Infrastructure". This model has the advantage of transparent ownership and gives users the opportunity to invest in the early stages of the project - everyone on Althea has the opportunity to become a major stakeholder and influence the direction of the project. Althea L1 provides fast finality, low-cost payment settlement, integrated EVM, and light client verification capabilities (described in detail later). Its architecture flexibly supports the construction of various DePIN-related networks, and is more like providing a settlement layer or aggregation function for micro-networks; similar to L1/L2 that focuses on building an RWA or DeFi application ecosystem.

Althea's core technical innovations are derived from two papers, Chapin & Kunzinger (2006) and Chrobozek & Schinazi (2021), which enable nodes in the network to achieve autonomous metering and settlement based on micropayments through its blockchain architecture. This innovation is called the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) and is the core support for its operation. The following roles are defined in the Althea network:

User Nodes: Installed by individuals, they are very similar to traditional ISP routers/modems, but operate independently of any ISP. These nodes provide WiFi and LAN connectivity to devices in the Althea network.

Intermediary nodes: Installed by connectivity service providers who wish to profit from forwarding Internet traffic. These nodes require more granular placement to get a better view of the traffic being received.

Gateway Nodes: Specialized versions of Intermediary Nodes that “connect the Althea network directly to the wider internet through low-cost sources such as Internet Exchange Points or business-grade connections from traditional ISPs.”

Exit nodes: Deployed in data centers, accessible via the internet, connect to these gateway nodes via “VPN tunnels” — these are secure, encrypted channels between user device connections and the internet. Exit nodes in Althea are responsible for measuring network quality and handling ISP “legal responsibilities” (copyright issues and address translation).

Althea’s routing is managed by the Babel protocol, which “checks the quality of service of each router on a specific path and provides a composite score to compare with other potential paths,” ensuring Althea can provide the highest quality service and faster connection speeds.

The above micropayment function is achieved by establishing internal accounts for each neighboring node in the network through the Althea router. Bandwidth is metered, tracked and used according to specific tasks, and payments are automatically completed and recorded on the chain. Althea adopts a "pay first, pay later" model to avoid over-reliance on trust assumptions, because in the "prepayment" model, malicious nodes are more likely to hinder new customers from using Althea.

User attraction is one of the main problems facing Althea - since Solana has become the main choice for DePIN projects due to its extremely low cost, compressed NFTs and high throughput, there is insufficient demand for teams that want to build networks on L1. What is the point of a high-performance L1 if there is no differentiated advantage over the public chain with existing users and liquidity?

It is not clear what types of DePIN projects Althea prefers to launch in its network, although the team does a pretty good job of communicating and seems active. The concept of an L1 designed specifically for DePIN is also interesting - the only other vertical-specific L1s we have seen so far are Plume (for RWA), Immutable (for games), and Filecoin (for storage). If the DePIN space continues to attract more high-quality teams to deploy projects with real products, Althea has a chance to find its place in this space.

The most uncertain outlook for fixed wireless is in the area of mobile wireless, which depends on the evolution of mobile wireless technology. On the one hand, it is possible that 5G and 6G will not be able to reach the same performance level as fixed broadband in the short to medium term, allowing the latter to maintain its current market position; on the other hand, 5G, 6G and low-orbit satellite broadband may completely replace fixed wireless services faster than expected. While it is generally unwise to bet on slowing technology development, there are still many variables surrounding the development of mobile wireless technology, which provides a reasonable development space for alternative fixed wireless solutions.

WiFi

The last segment of DeWi is WiFi, which is ubiquitous but does not account for a large share of the wireless service revenue market. This is mainly due to its difficulty in making money: consumers are accustomed to enjoying free WiFi everywhere, so telecom operators such as AT&T, Comcast and Spectrum build large public WiFi networks mainly to divert mobile data traffic or enhance customer stickiness.

On the enterprise side, such contracts are usually long-term agreements signed with WiFi suppliers, which helps improve user retention. Frankly speaking, this may be the least attractive construction area: the market is already flooded with a large number of low-priced supplies. In remote areas, users' willingness and ability to pay are extremely limited, making it difficult to form a "blood-sucking" impact on traditional suppliers.

Of course, WiFi is still the most widely used connection protocol in the world, compatible with the most diverse devices. Almost all devices in our homes can connect to WiFi now, and there will be more smart devices in the future. In some ways, WiFi is like the basic language that supports all network interactions. But this does not necessarily make it the future track with the most disruptive potential and value capture space.

This situation may explain why there are relatively few builders in this field. The most well-known WiFi DePIN teams include Dabba and WiCrypt.

Dabba

Dabba is building a decentralized connectivity network with a focus on the Indian market. The team’s current strategy is to prioritize the deployment of low-cost hotspot devices, similar to Helium but focused on the WiFi field - more than 14,000 hotspots have been deployed so far, with network data consumption exceeding 384TB.

Their core concept is based on the background of India's economic growth and the needs of its huge population. The country needs to build more efficient infrastructure to compete with centralized service providers in terms of uptime and accessibility. Instead of blindly pursuing the number of hotspots, the team first deployed the equipment in areas with high data demand and laid the initial foundation for the project through word-of-mouth communication.

In a blog post late last year, the team shared an overview of India’s telecommunications industry: Although the population exceeds 1.4 billion, there are only 33 million broadband service users and only 10 million 5G network users.

Today, Dabba’s priority is to expand its network and reduce friction to join. Dabba believes that while 4G and 5G connectivity are necessary, Indian businesses and homes need fiber to facilitate connectivity between these mobile and fixed broadband networks. Over time, the goal is to build the largest, most decentralized network to power India at a lower cost.

The network architecture is quite simple: The stakeholders of the Dabba network include hotspot owners, data consumers and the Local Cable Operators (LCOs) who manage the relationship between the providers and consumers. Their strategy has shifted towards targeting some of the more remote areas of India through the LCO network, after initially deploying in densely populated cities where the demand for WiFi is high.

WiCrypt

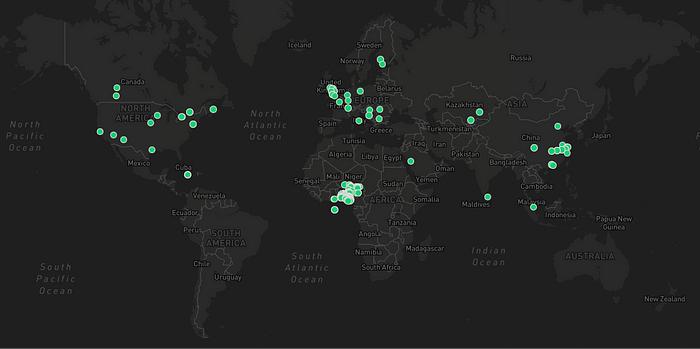

Another project building a decentralized WiFi infrastructure is WiCrypt — they hope to enable anyone to become an Internet service provider through a dynamic cost structure and a global network of hotspots. This looks similar to what Dabba is building, focusing on enabling individuals or businesses to share WiFi bandwidth for a fee. According to the WiCrypt browser, more than $290,000 in rewards have been issued and considerable network coverage has been established in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the United States.

Admittedly, the network size is much smaller than other projects we have observed so far. The WiCrypt whitepaper specifically points out several major problem areas:

- Countries that censor internet content

- ISP oligopoly industry with nine companies monopolizing more than 95% of revenue

- Abuse and cross-border behavior of existing ISPs

These points hit home, highlighting the core problem that gave rise to decentralized wireless networks - consumers are forced to accept suboptimal options and often cannot afford the switching costs. WiCrypt aims to enable anyone to become an ISP sub-retailer, enabling them to set more favorable terms outside of existing infrastructure and commercial terms. Given the current popularity of public WiFi, this business model seems challenging. From a capital perspective, it is also difficult to imagine that the demand side (i.e. users who need network access) is large enough to incentivize continued investment on the supply side.

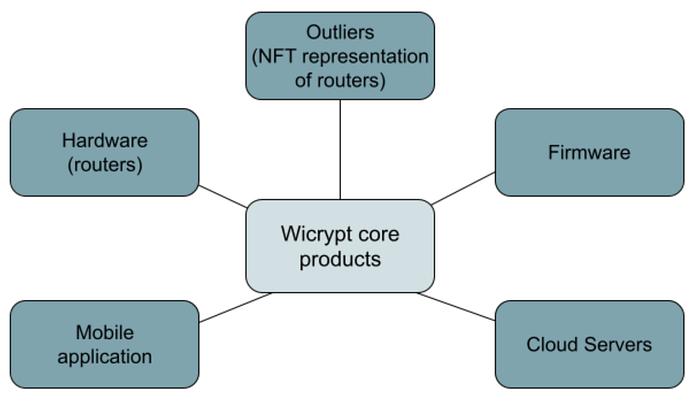

WiCrypt's architecture includes: hardware (hotspot device), mobile application (for ease of use), router, cloud server, and firmware. The router batches all incoming transactions and uploads them to the blockchain, and then manages "traffic control" and router activities by interacting with the Linux-based firmware. Users use the WiCrypt mobile application to handle market-related operations such as WNT token payments, identity verification, and data management. The cloud server connects to the smart contract and confirms the data proof as a secondary verification mechanism for on-chain information.

Decentralized wireless networks deserve a lot of attention, as the benefits are huge if they succeed. The telecommunications industry supports the communication needs of the world at work, life, and leisure. Decentralizing this technology stack is a difficult task, but it is still worth exploring given the uncertainty of the future development of traditional telecommunications. Coupled with the huge rewards that can be brought by successful execution in this vertical, it is clear that we will continue to see fierce competition.

The recent market recognition of Helium's success proves that builders do not need to pay too much attention to market evaluation, and the key is to continue to create value for the network. This value creation will eventually be recognized. It also shows that traditional operators such as T-Mobile and Telefonica are willing to embrace this paradigm shift.

If you thought the telecommunications industry had inefficient, outdated, and poorly managed infrastructure, wait until the next chapter: decentralized energy grids.

Energy

We have written about distributed energy many times before. We touched on it in our Crypto Future report in early 2023, and later conducted a special analysis in our public research database. Although few people were interested in this area at the time, distributed energy is now clearly gaining more and more attention.

The energy industry remains one of the most strictly regulated monopolies in the United States, and it is also one of the industries most suitable for the DePIN model. The energy market is extremely complex in many dimensions: hardware equipment, energy capture, transmission network, financing mechanism, energy storage technology, distribution system and pricing system.

Renewable energy does have important policy benefits, especially at the regulatory level. But solar panels are expensive, not suitable for all regions, and the return on financing for upfront investment has been unsatisfactory. Battery technology is becoming more efficient and cheaper, and the ideal vision in the field of renewable energy is a combination of "solar + storage". Nuclear energy has been difficult to gain support even without the intervention of cryptocurrency.

One of the biggest problems facing renewable energy today is that most sources are intermittent and dependent on weather conditions (e.g., wind is erratic, sunlight is not constant). It is also challenging to integrate these energy sources into the existing power grid—the grid must manage fluctuating power levels, which can put a strain on the infrastructure. Traditional grid design is based on a one-wa