We’ve previously talked about the properties of the widely used MetaMask service. Those posts specifically detail ways in which the service clearly has an operator and users are not “fully” in control of their assets when certain features are used. While some parts of the system are “non-custodial,” others pass control to a central operator.

That was in July 2024.

In February 2025, ByBit was hacked for well over a billion dollars’ worth of of crypto-assets. This resulted in widespread change throughout web3.

Many of these changes grew directly from the hack, forcing “developers” to recognize they were also “operators” at least some of the time.

And as operators, these people feared processing funds stolen from ByBit and eventually facing prosecution, with some products introducing explicit screening or closing outright.

What is important here with respect to MetaMask — the reason a Part IV is being added — is that OKX shut down their decentralized exchange aggregator on March 17, 2025 and the technical details of that shutdown mirror almost exactly what MetaMask could do to shut down (or add compliance functions to), their own swap router.

Here we will do three things.

First we will explore how OKX shut down their router. That discussion is technical enough to be precise but not exceedingly so as the process was not particularly complicated. Anyone with a casual understanding of smart contracts should be able to follow it.

Second, we will show, again with precise details, how MetaMask can do the same thing that OKX did. Readers that cannot follow the technical details in either of those parts should still be able to recognize that the processes rhyme.

Finally, we will conclude by using this example to address a legal argument made to refute our original series of posts. To preview that component, either the lawyers defending these products do not know how these systems work or there is a belief that their audience does not know how they work.

By proving that MetaMask can do exactly what OKX did, we call into serious question MetaMask’s alleged lack of control over its system.

How OKX Shut Down Their DEX Aggregator

To understand how OKX effected the shutdown of its DEX aggregator we will go through three steps. First, we trace a user swap transaction through OKX’s aggregator to identify candidate control points. Second, we will analyze the specific transactions which shut down the aggregator. Finally, we will discuss the issue of “immutability” and consider the extent to which the components surveyed really are “immutable” in their purest sense.

Tracing A Transaction

We will begin our analysis by tracing the 0x56ca44c1b835a822b6a6c2ecc25aaa38ae382ebe531ed3930403098509c9be83 transaction on the Ethereum blockchain. This is a typical user transaction that begins at a front-end called Krystal and proceeds through OKX’s DEX aggregator for eventual execution on Uniswap.

This transaction is initiated by an end user call to a proxy contract for the Krystal router with an implementation contact labelled as SmartWalletImplementation.

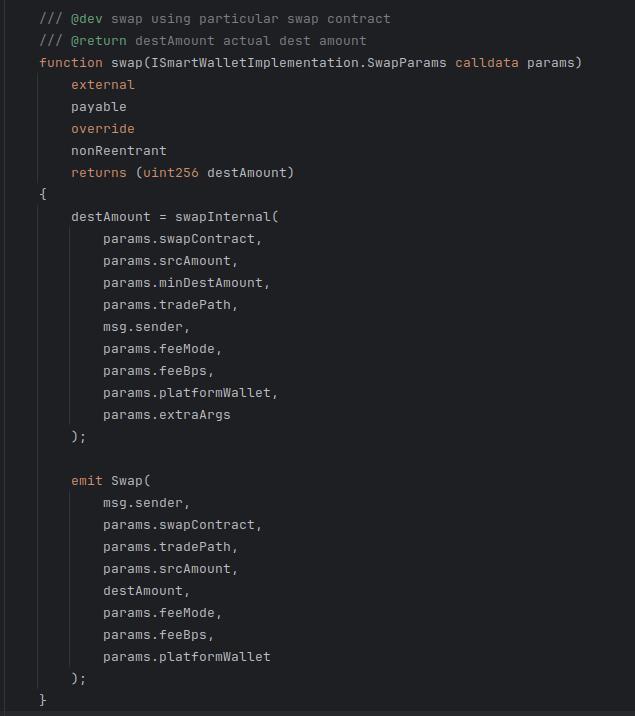

The end user calls the swap() function on this implementation which invokes the following code:

This is itself a thin wrapper over swapInternal():

The important part of this function is where it calls the swap() function on the contract located at address “swapContract” which is itself a function input parameter on the swap() call.

The end user specified swapContract as a way of instructing this Krystal router how they wanted their swap executed. The execution style was selected by the end user.

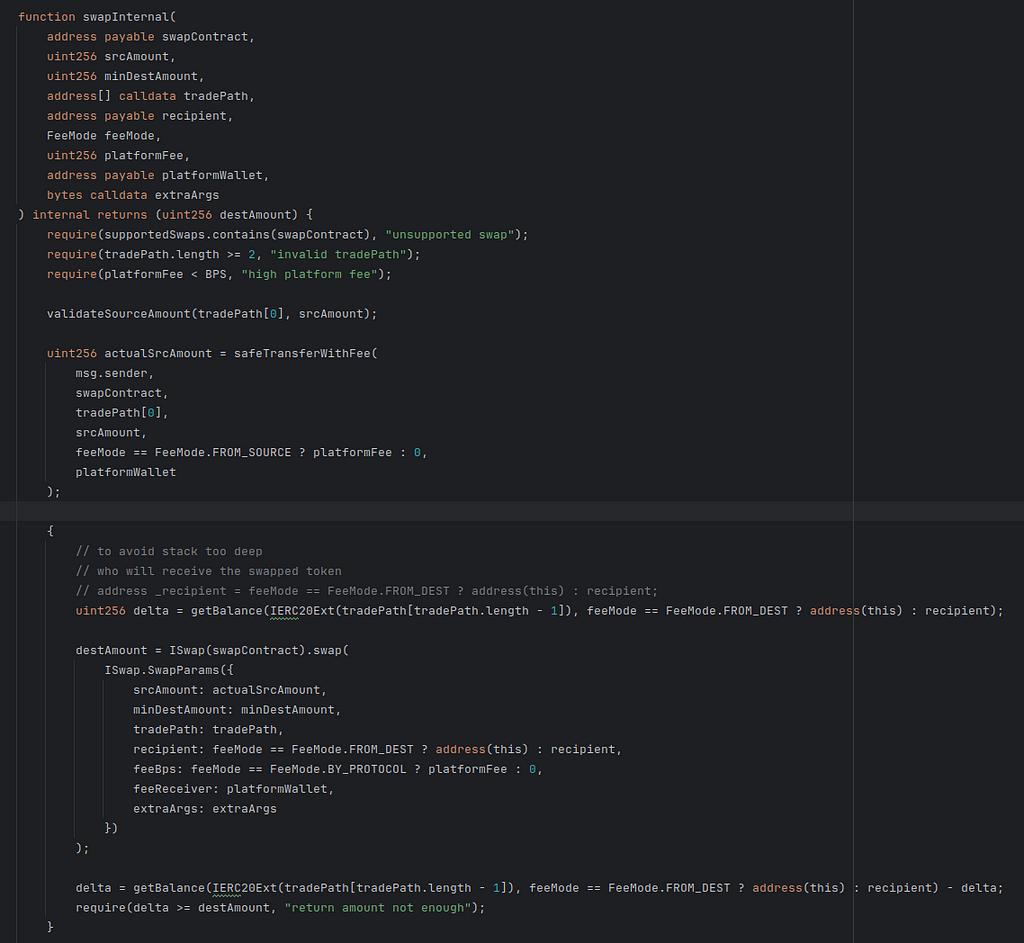

Then we see the specified swapContract, visible in the initial transaction, is a contract labelled as Okx.

The swap() function there is:

The user asked to execute through the OKX aggregator product, and it in turn, relies on a “router” value which is maintained inside the OKX contract by whoever controls the OKX contract. It may be “immutable” in some sense, but the contract has an admin currently set to an EOA.

So someone holds private keys off-chain and can control the admin interface.

To review, the user exercised discretion to direct Krystal to the OKX aggregator. Krystal was passive here. But the OKX aggregator’s admin also has some control over the ensuing flows. The administrator also has a form of discretion here.

This interface allows, among other things, changing the “routing table” used by the “router” to reroute trades. There is even a comment visible in the code snippet “Okx API will return[] calls nec[]essary to build tx” which makes explicit that OKX is actively involved in routing these transactions.

This does not mean OKX takes an active role in each and every execution — but it is not entirely passive either.

We can find the router by querying the contract and it is a different piece of code labelled OKX DEX.

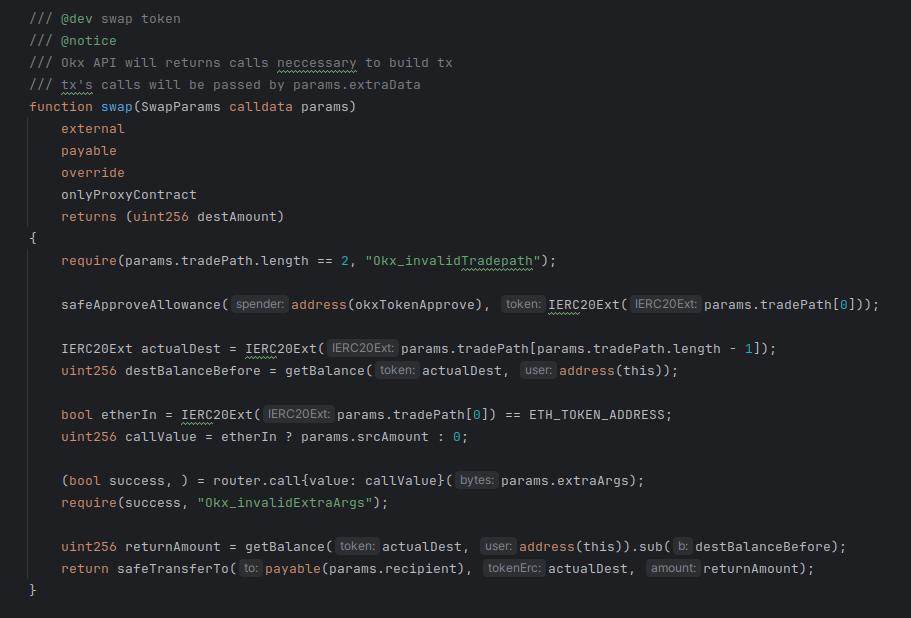

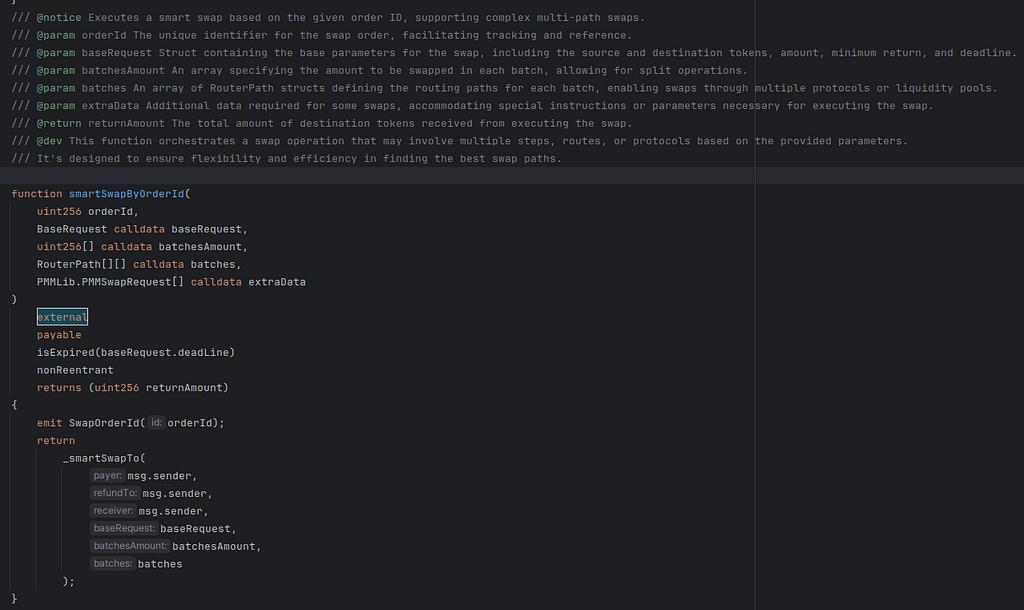

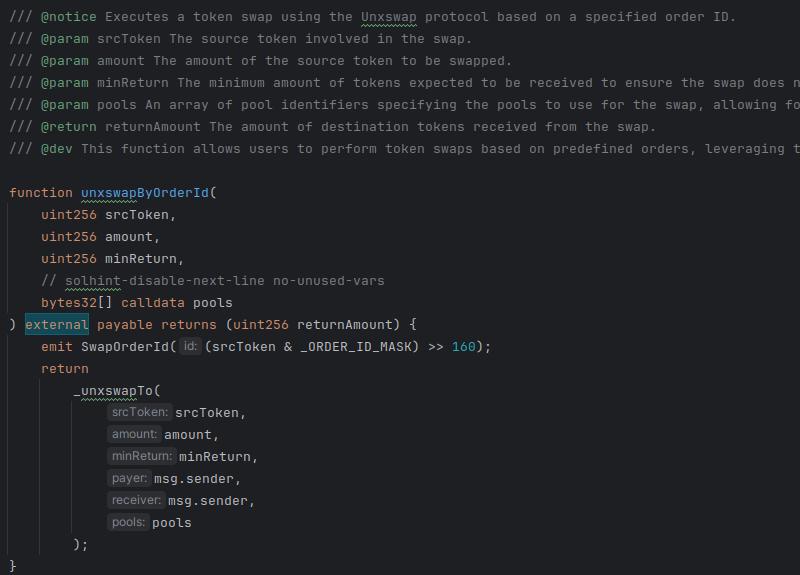

That is a proxy contract with implementation labelled DexRouter. This is the core of the OKX DEX. Here are two of the swap functions it offers:

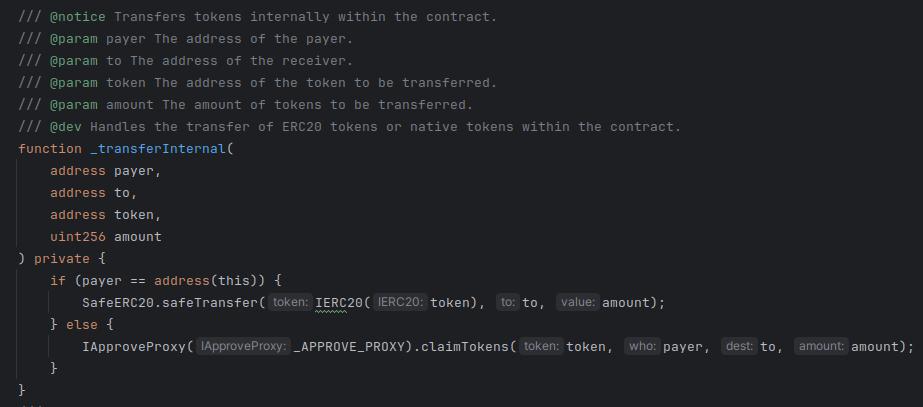

There are in fact many other such wrappers with a range of helper functions inside. All of those paths through the code end up somewhere like this:

The key part here is that an ApproveProxy gates flows through this contract.

If ApproveProxy makes the approval, only then do the tokens flow through the contract, if there is no approval by ApproveProxy, the tokens do not flow through the contract.

Notice that before the ByBit hack even started there was already embedded with the OKX DEX aggregator something like a compliance function. It was not enforcing anything like traditional financial services compliance, but the structure was already in place well before this incident.

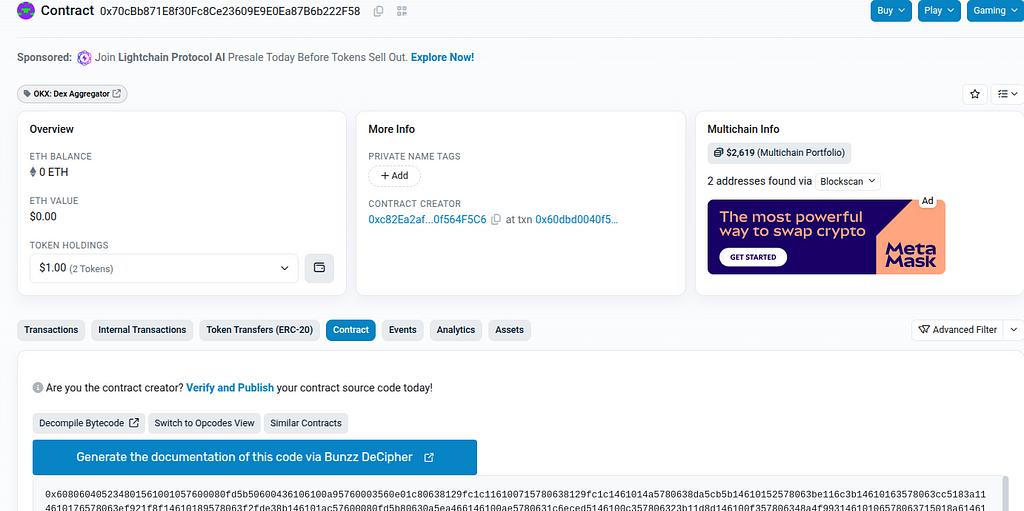

And again we can find the address of ApproveProxy by querying the contract. It turns out to be another contract labelled “OKX: Dex Aggregator” and the contract is closed source:

So we do not know precisely what this “compliance” function does. But we can see it sits in a privledged position inside the OKX DEX aggregator software with the abiltiy to control much of the process.

The smart contract ApproveProxy gates token flows through the OKX DEX aggregator. If one can close these gates then one can shut down the aggregator.

As we will show in the next section it is this approval contract that was shut down by OKX, effectively shutting down the OKX DEX aggregator.

Returning back to the original swap transaction, as can be seen on the initiating transaction, the router eventually forwards the assets to Uniswap for execution.

The router, alongside the other points of control in this sequence of events, eventually remits the proceeds of the swap to the end user with fees extracted along the way.

The Shut Down

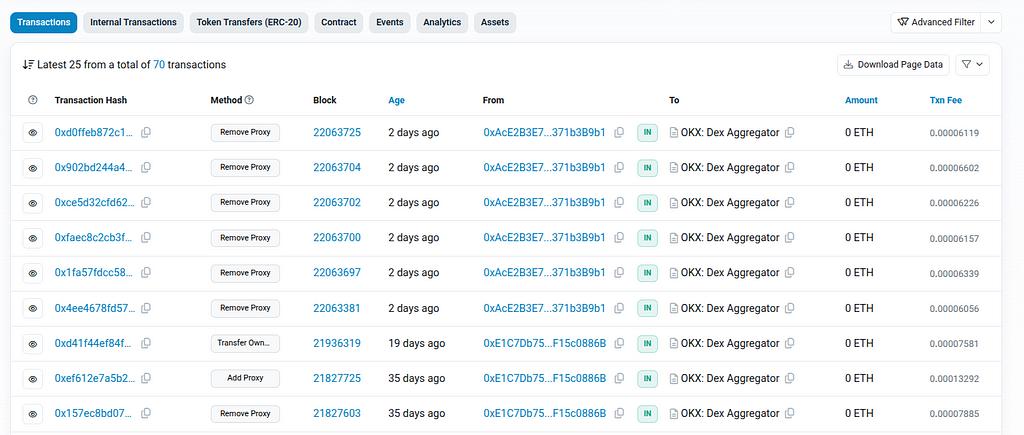

While the ApproveProxy contract is closed-source we can still see function calls going in:

And while we cannot know for sure what is happening inside these calls because the code is unavailable (closed source), we can see the name and parameters.

Given that information, which we will now lay out, it looks safe to make a few educated guesses as to what functions ApproveProxy performs.

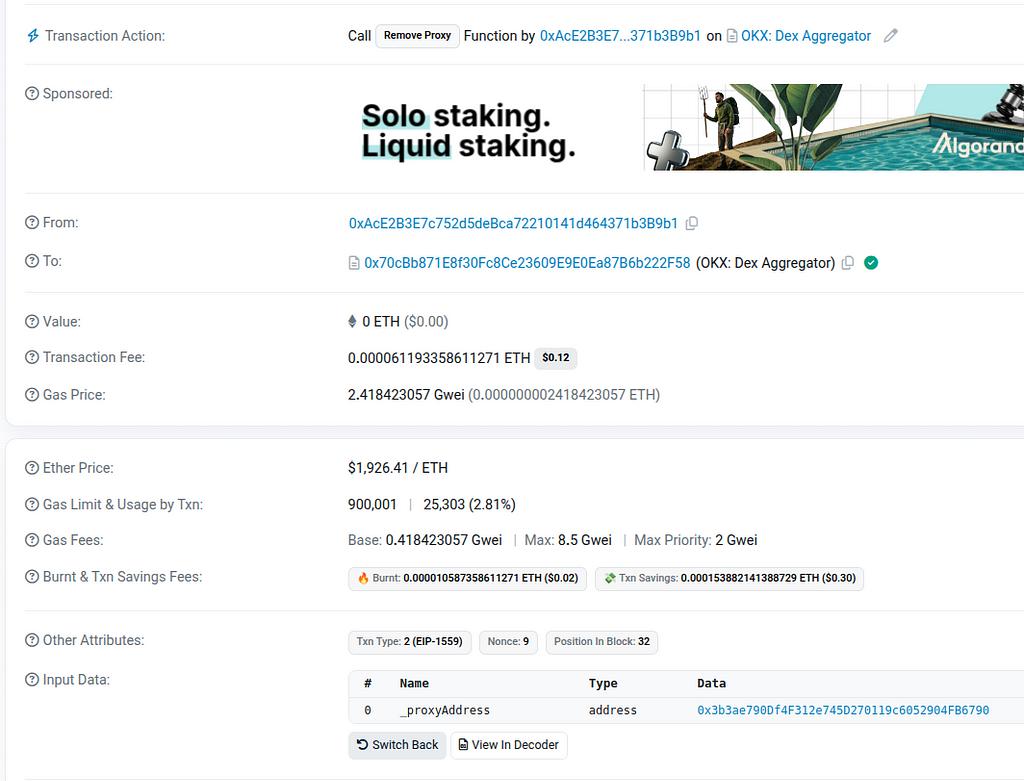

The calls are to removeProxy() with a specified “_proxyAddress” as the sole input. Here is the function call to removeProxy() the proxy we used above:

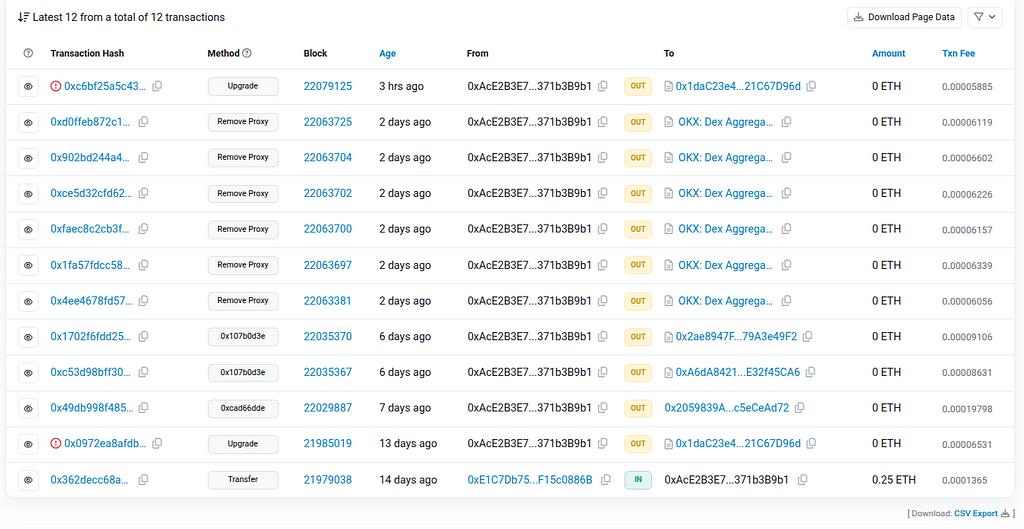

This function was called 6 times in quick succession co-incident with OKX’s announcement. All 6 calls were initiated by the same EOA which, unsurprisingly, is also linked through prior funding to the OKX DEX:

We do not have the source code for the gating contract but we can see:

- 6 calls to removeProxy() coincident with the shutdown announcement

- The parameters to those calls match OKX DEX proxies

- The caller is linked to OKX DEX

So as an educated guess we are seeing the owner of the ApproveProxy contract removing all the acceptable proxies. Then, again as an educated guess, these removals effectively shut down the OKX DEX aggregator.

Immutable What?

Smart contracts on Ethereum and other platforms are often described as “immutable by design” even though there are simple and common design patterns employed for decades to achieve mutability in these sorts of environments.

All the contracts referenced above are “immutable” in the specific technical sense that their code cannot be modified post-deployment.

But substantially all of them are mutable in the practical sense that standard software engineering techniques empower owners to make changes to the code end users interact with.

The software code is immutable. And standard techniques to achieve mutability operate on mutable data referenced by the immutable code to redirect execution to new blocks of code.

These techniques were already common when computers were made from vacuum tubes rather than silicon. None of this is new.

That is how OKX was able to shut down a platform running “immutable” code — OKX updated mutable data under their control to redirect the “immutable” code in the way OKX wanted.

How MetaMask Can Do The Same

We have previously written about mutability in MetaMask with respect to swaps, staking, and bridging. At a high level MetaMask’s swap function works as a combination of the SmartWalletImplementation and OKX DEX aggregator given above.

Rather than rehashing the entire discussion of MetaMask’s design from our prior work we will simply map out how the objects MetaMask calls “aggregators” and “adapters” match the OKX framework.

It is then straightforward to understand how MetaMask can shutdown its service if they wanted to.

From there we discuss some claims made about the MetaMask design that appear inconsistent with how the software actually operates.

Adapters

When executing a swap with MetaMask the user specifies an “aggregator.” This is a string like “oneInchV5FeeDynamic” which tells the system how the user wants their swap executed. For those familiar with traditional markets this is just an execution strategy.

The MetaMask code maintains a table of adapters for each supported execution strategy. This is a simple routing table that matches strings to addresses.

In the case of OKX, the end user specified an address, for Metamask the user specifies a string and the system then looks up the address of the adapter.

Many of these adapters are closed source, but Metamask, when executing user swaps, passes control to the closed-source code for execution and transmits the results back to the end user.

MetaMask’s routing table can be dynamically updated and the team behind Metamask actively manages this routing table.

The smart contract has an owner with the ability to add and remove entries from the routing table. This occurs routinely with dozens of updates over a multi-year period. The MetaMask team actively manages this routing table.

MetaMask is part of Consensys. In Consensys’ response to a now-dropped SEC case “Conensys admits that MetaMask Swaps is Consensys-developed and Consensys-maintained software.”

In that same filing they go on to state, in paragraph 3, that Consensys “routes investor orders” with respect to this same software. As we will see they can and do control where orders flow and can even choose to prevent orders from flowing entirely or insert their own screening processes within the current architecture. Whether that constitutes routing is outside the scope of this discussion.

Further, in paragraph 104 of the same document, Consensys denies that it “exercises further discretion” over what it makes available to users. However, as we will see, Metamask has total control over the product’s offerings and could, through what is functionally identical to their normal maintenance procedures, install any sort of screening program a regulator or court deems necessary.

MetaMask can comply with virtually any court order, including one to shut down the protocol, without taking any extraordinary actions relative to their normal maintenance procedures, indicating a substantial degree of control.

OKX held the same degree of control though nearly-identical technical means and shut down their service.

OKX’s control over their DEX aggregator was not theoretical, it was actual because they both possessed sufficient control to shut down the DEX aggregator, and exercised that control.

OKX could even turn it the DEX aggregator back on by rearranging the routing table so that it would work again, if it ever so decided.

Because MetaMask is in the same position this implies that MetaMask must also have the same degree of control over its software regardless if they choose to exercise it.

Now we will explore how Metamask’s control would work.

How MetaMask Can Brick Their Device

This part revolves around the standard maintenance procedures for the routing table. The owner is not able to replace entries in the table — they can only remove them, and the owner is not able to remove all entries from the table because the table cannot be empty. So the software as deployed constrains the owner’s choices slightly.

But the owner can set any address they like as an entry to the routing table.

So they are perfectly capable of putting the routing table in a state where the only active adapters are non-functional contracts that generate errors rather than execute swaps.

As is discussed below this also means the owner is capable of installing adapters that only comply with court orders or otherwise manage the table and adapters such that any behavior expressible in computer code is achieved.

Bricking the device can be achieved by adding a non-functioning adapter and then removing all the others.

Notice OKX is not trying to prevent people from calling swap(). Rather they are ensuring that if anyone does call swap(), nothing useful happens. This is separate from any front-end changes that might occur.

In this case, it wasn’t as if OKX only shut down the front end, while the immutable back end continued to process trades.

OKX bricked the on-chain smart contracts ensuring nobody could transact using the DEX aggregator even if someone was determined to write their own front end from scratch to interact with the DEX aggregator.

MetaMask can do the same thing.

Crypto-Lawyer Gaps

In an analysis of our MetaMask claims the General Counsel of Variant Fund wrote:

Assuming the adapters are not malicious (which would be another issue entirely), their job is to enable a user to perform an atomic swap — in a single transaction take token A and exchange it for token B.

This same lawyer, when at Cravath, worked on Coinbase’s SEC defense and put forward similar arguments and appears to be the best defense for how this type of software is “non-custodial.”

Now consider what the quoted sentence means in the current context.

OKX was, in one sense, being “malicious” with respect to users that still wanted to swap crypto-assets. However, admitting they could be “malicious” in this way is also admitting that OKX could shut down the protocol.

OKX was “malicious” with respect to North Korea’s potential use of the system. However, the power to be malicious is control. Absent control being malicious is just thinking bad thoughts.

In this context, who someone is malicious against is a form of “compliance.”

Examples abound of financial intermediaries with control and inadequate compliance. This could be another such example.

Even well-intentioned and morally justifiable exercises of control can emerge from wholly non-compliant governance procedures.

We do not view the argument advanced above as an error insomuch as it is a manifestation of a general lack of software engineering experience.

Toe be fair, writing code to a simple specification is one matter, however understanding how complex software systems grow and are maintained is quite another.

These adapters are both simple automatons and components of a large control vector with decidedly non-trivial properties.

Software that looks simple often exhibits unexpected and complex behaviors when implemented.

Learning to identify and manage that problem is part and parcel of real-world software engineering experience, and lawyers can’t be expected to know off hand.

The power MetaMask holds here is not unique.

Many other products have these “hidden” control levers, raising serious questions regarding control, liability, and accountability.

It is challenging to assert that a party with the ability to shut down a product has zero liability for their product’s use so long as they act in good faith and are never “malicious.”

Such a position necessarily begs the question “malicious with respect to who?”

The Lazarus Group is a North Korean-state-linked actor. Any company with an obligation to be malicious with respect to North Korea has the obligation because of the decisions of the government under which they are incorporated, where their team lives or banks, or something within the existing legal system.

If operators of these systems are simply choosing to be malicious of their own accord, and directing that maliciousness to parties of their choosing, that may raise other serious legal issues.

Note that completely “freezing” the system is not the only discretion operators can exercise.

OKX, MetaMask and a range of other actors could also choose to redirect systems already under their control to filter transactions through whatever software they wanted.

It is entirely within these operator’s controls to implement traditional screening functions for suspicious transactions if they deemed it appropriate.

This is in line with Van Loon v US Department of The Treasury where, with respect to mixers and their owners, the court wrote:

For example, if a mixer was mutable — or in other words, controllable or custodial — the mixer’s operator or owner could offer to mix deposits, which a third-party user could accept by transferring Ether to the operator’s mixer-smart contract.

If you own a mutable contract then you, as the owner, can enter into contracts with users. When you transact you are entering into such contracts. That places you wholly inside the relevant legal systems with respect to the activities of your owned contracts.

Whether access to an “ON” and “OFF” switch in and of itself constitutes a specific form of control under legal standards may be up for debate.

However insofar as the design of OKX and MetaMask’s routers goes, the owner could enforce court orders without deviating from their current engineering practices.

While it is possible for a court order to differ from an existing policy of the owner, a difference in policy is not the same as a difference in possibility.

Part IV: MetaMask, The ByBit Hack & OKX Bricking Their Router was originally published in ChainArgos on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.