Translation | GaryMa Wu Blockchain

Original Link:

https://www.anza.xyz/blog/the-path-to-decentralized-nasdaq

Abstract

Solana aims to build a decentralized trading network more efficient than Nasdaq, but current blockchain design falls short. Solana market makers currently have a low win rate in order cancellation races (far below 13% of centralized exchanges), and Jito auctions exacerbate a single leader's control over state access, leading to widening spreads. In response, they propose reconstructing the consensus mechanism by introducing concurrent leaders to optimize order sorting and reduce market makers' adverse selection costs, thereby improving price efficiency.

Solana's initial creation goal was to build a blockchain fast and cheap enough to run a viable central limit order book. The Solana mainnet beta launched in March 2020 — five years have passed, and while we've achieved many accomplishments, it's becoming increasingly clear that we haven't yet achieved this goal.

Existing blockchain infrastructure was not designed for trading. If we want to achieve Solana's original mission, we must go back to the basics, fundamentally redesign the consensus mechanism from first principles, and ultimately build a decentralized network capable of competing with the New York Stock Exchange.

When we say competing with the New York Stock Exchange, we mean that exchanges on Solana need to provide better prices than centralized exchanges. In the market world, price is defined by the "spread": the difference between the highest price someone is willing to buy an asset and the lowest price someone is willing to sell an asset.

The smaller the spread, the better the price traders get, and the more efficient the market.

The spread formula is simple. The spread is set so that the market maker's expected earnings from trading with non-informed traders equal their expected losses from trading with informed traders. When market makers have more information than their counterparties, they make money; when they have less information, they lose money. Market makers typically earn a little money in each trade with retail traders, but can lose a lot when prices jump dramatically (hopefully infrequently) if caught on the wrong side.

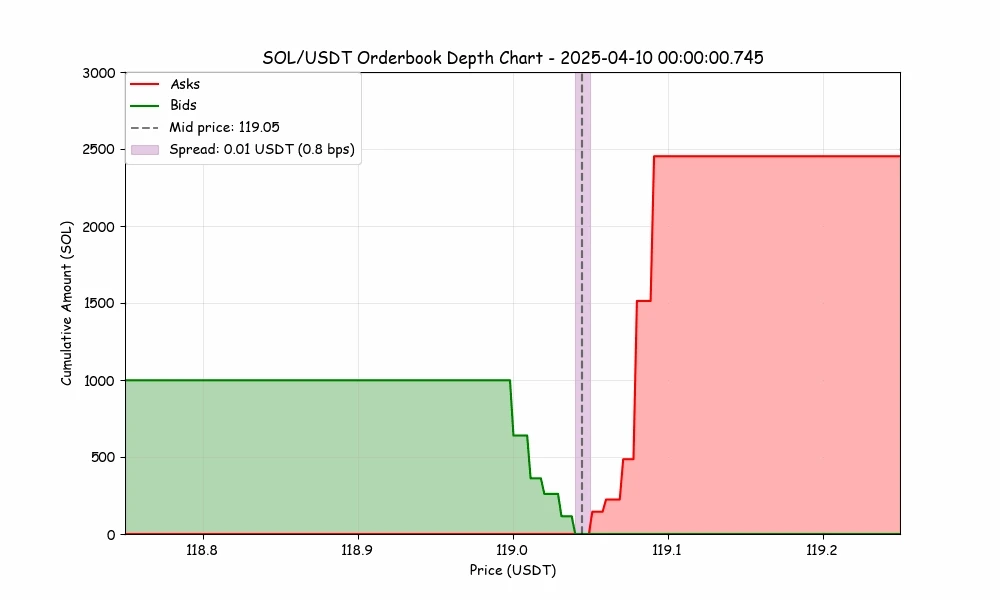

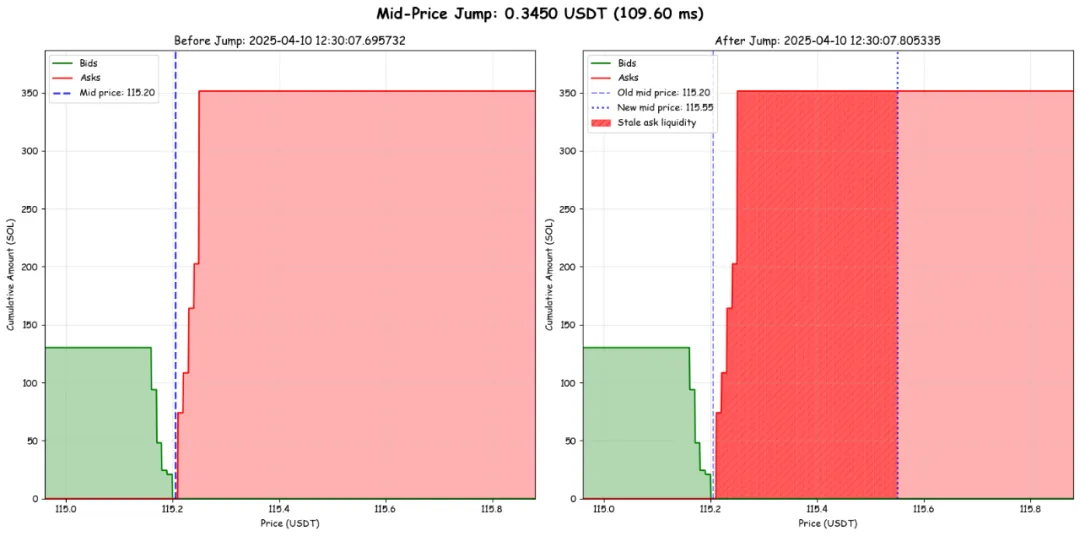

What Determines Adverse Selection Costs?

To better understand adverse selection, we need to understand the game market makers are playing. Market makers judge based on a "fair price" that randomly changes over time. When the fair price is within the bid-ask spread, the market maker's quote is safe because the counterparty cannot profit by taking the quote. But once the fair price exceeds the spread, a race begins: market makers try to quickly cancel orders, while the taker tries to grab the outdated quote before the market maker cancels. The successful taker hopes to profit from the difference between the fair price and the outdated quote. The key to reducing adverse selection friction is to make market makers win this race as much as possible.

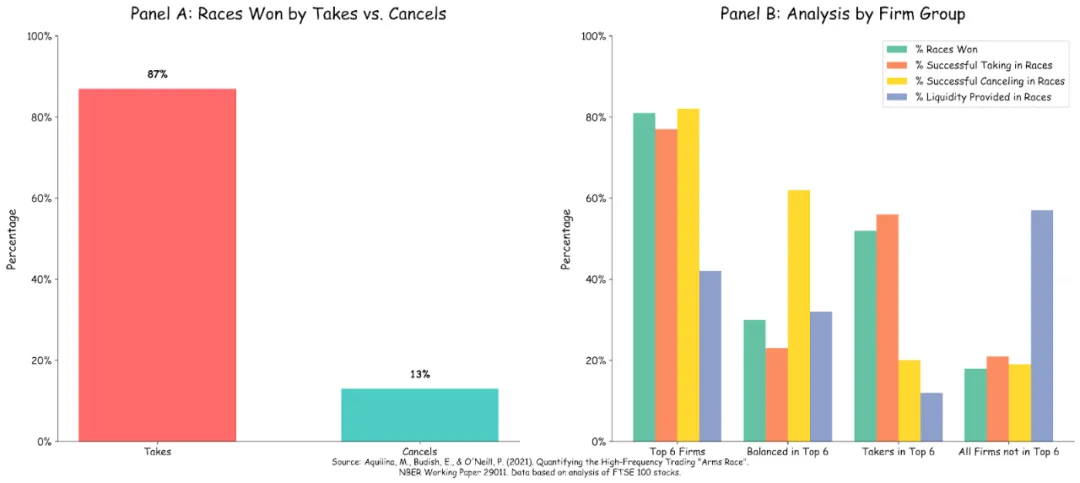

Data from a centralized exchange shows that market makers have only a 13% chance of canceling orders first after a price jump.

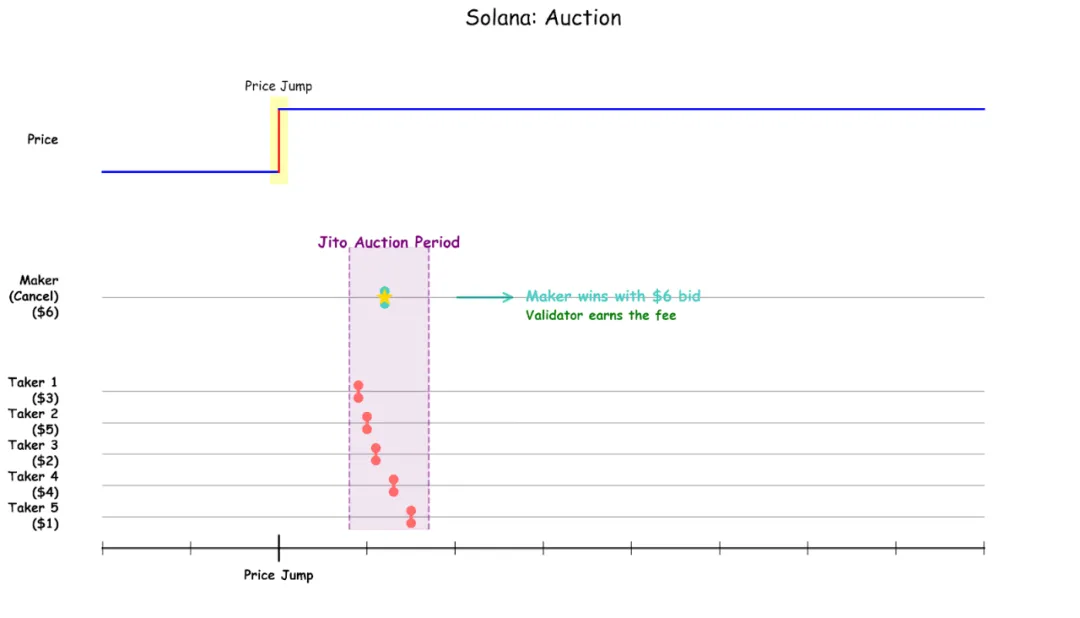

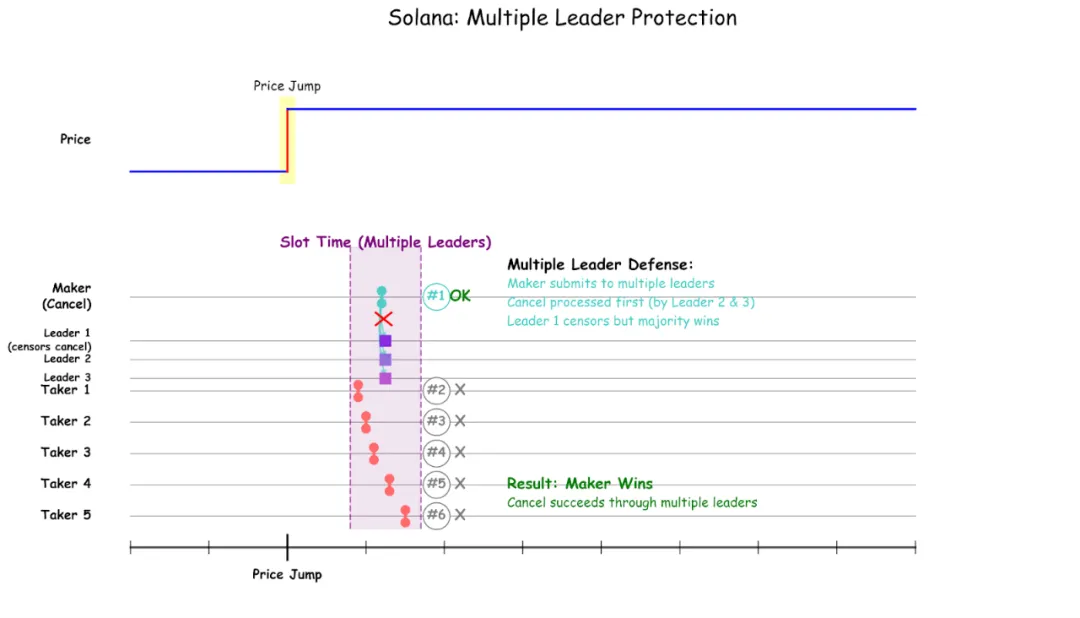

While centralized exchange market makers have a low probability of winning the cancellation race, it's even lower on Solana. The Jito auction mechanism — a side effect of a single proposer controlling state access for an extended period — makes it almost impossible for market makers to win the cancellation race. Even if market makers are faster, the real determinant is who bids higher in the Jito auction. This puts market makers in a dilemma: either spend a lot of money to cancel orders or let others bid high to snipe them. Either way, they're losing money and thus must widen the spread.

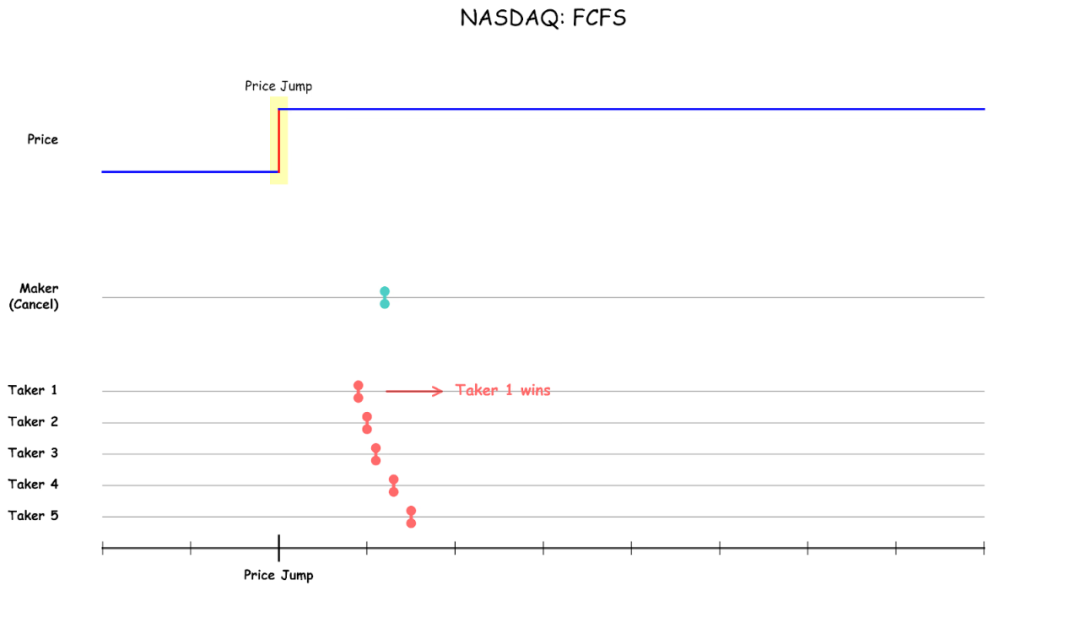

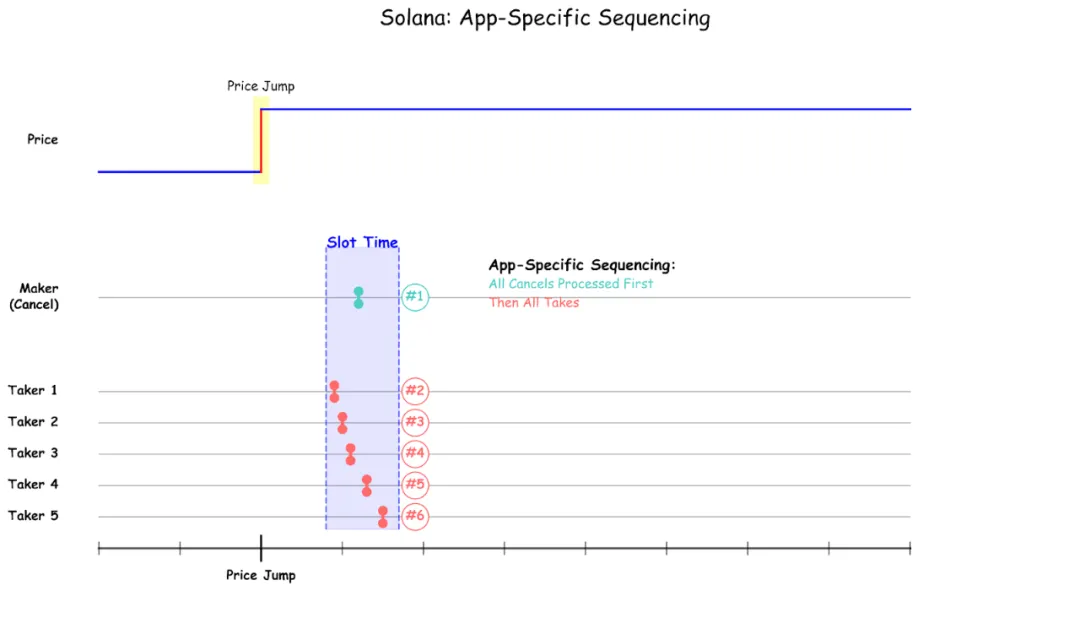

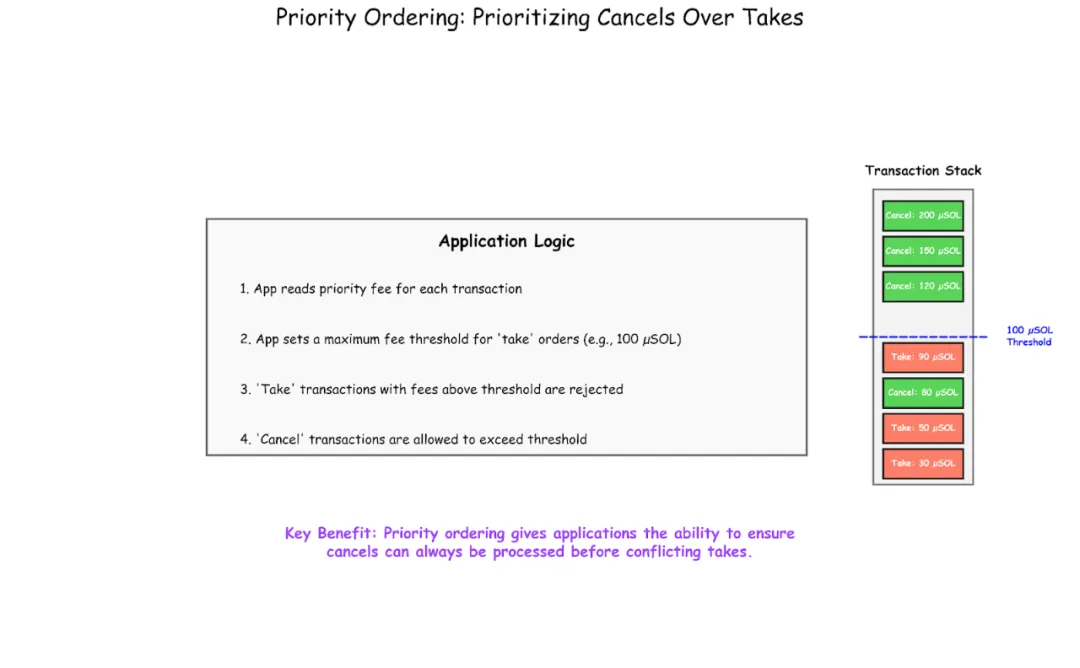

In practice, the current on-chain market microstructure essentially gives takers an initial advantage in adverse selection. To solve this, we need to give applications more transaction sorting flexibility. To reduce spreads, applications must be able to give market makers the upper hand in order cancellation races. One approach is to introduce a "cancel before trade" sorting strategy. We look at the block and process all cancel transactions before processing all take transactions.

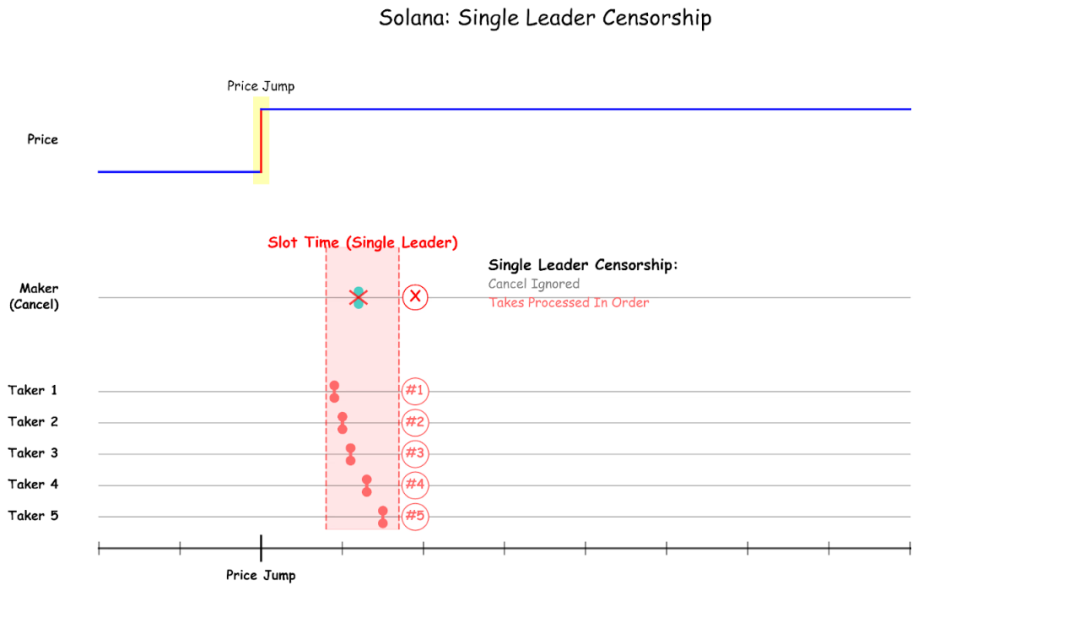

We can immediately implement this strategy on Solana by changing the current replay ordering from leader-determined to a strategy that prioritizes cancellations. But this doesn't completely solve the problem. If a single leader can still choose to ignore cancel transactions, we're back to square one — market makers are still at a disadvantage in the cancellation race.

The only solution is to introduce concurrent leaders. This way, if one leader blocks cancel transactions, you can submit to another leader.

Implementation — Transaction Sorting

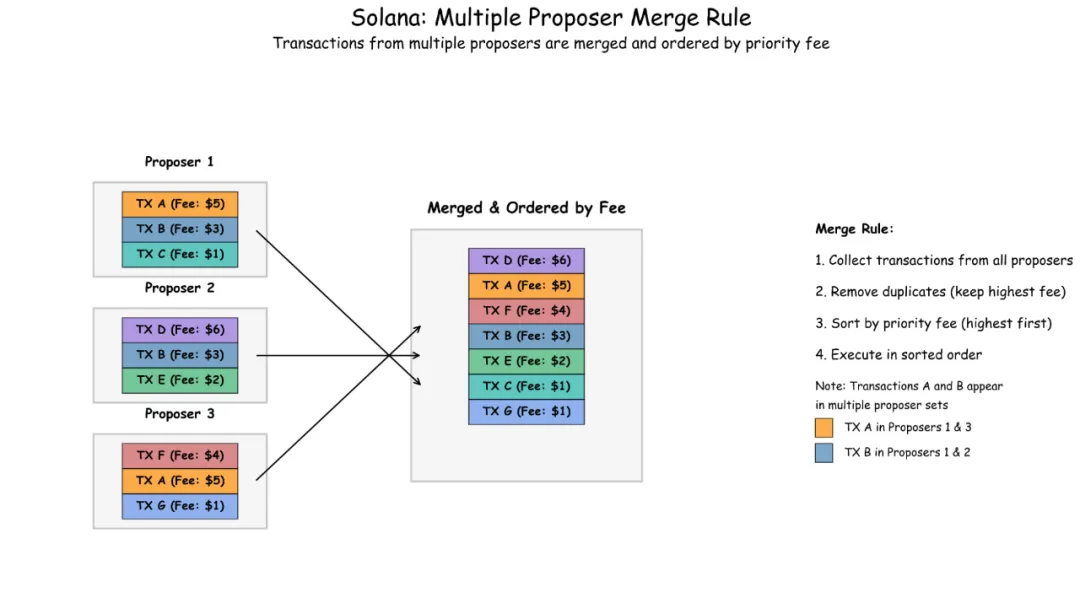

The biggest question about concurrent leaders is: How do we merge blocks when conflicts exist? The answer is simple: We divide fees into two categories: inclusion fees and ordering fees. Inclusion fees are paid to validators including the transaction, and ordering fees are paid to the protocol (burned). When merging blocks from different leaders, we simply take the union of all transactions from blocks in a slot and execute them sorted by their ordering fees.

This measure alone is not enough. What we really want is to allow applications more flexible control over transaction sorting. We add another element: the `get_transaction_metadata` system call, which allows programs to read the ordering fees of transactions interacting with them, providing applications with a powerful sorting control tool.

Implementation — Consensus Mechanism

Our consensus mechanism design goals include:

1. Binding & Blinding: Concurrent leaders cannot include information from other leaders' blocks (such as sandwiching private transactions) or cancel their own blocks based on other leaders' block contents (for example, canceling their own bid after seeing other bids).

2. Wallclock Fairness: Concurrent leaders must submit blocks in roughly the same real-time.

Here's a summary of the most effective solution developed in collaboration with a16z Research's Pranav Garimidi and Joachim Neu:

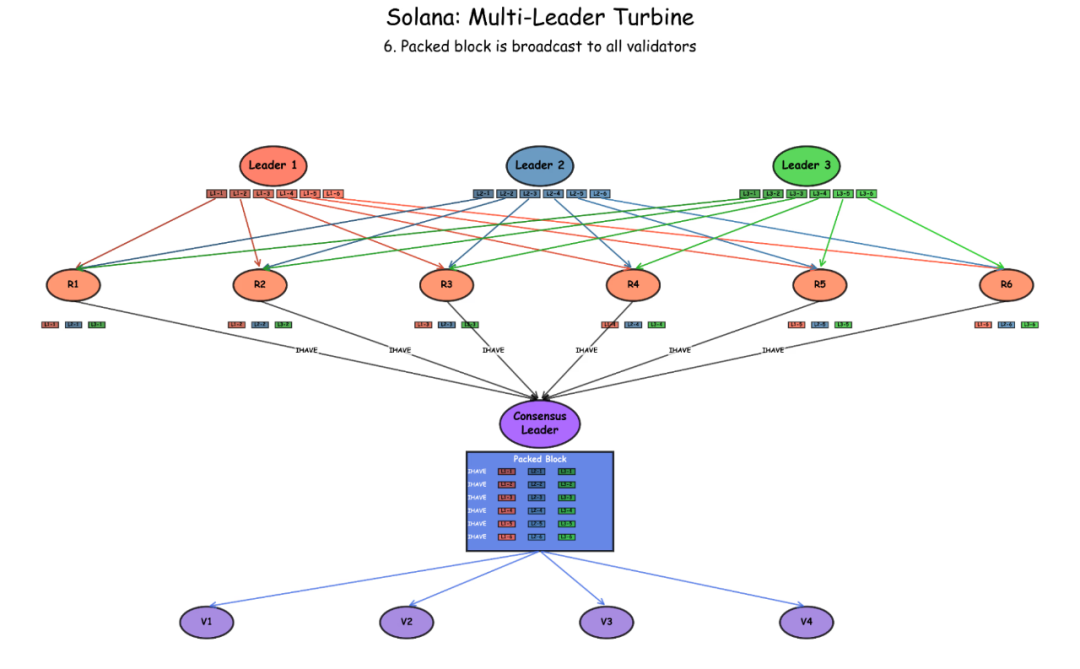

1. Each leader converts their block into erasure code shreds. Once enough shreds (above the encoding rate) are recovered, the block can be restored. Partial restoration is impossible.

2. Leaders send shreds to relay nodes in the first layer of the Turbine tree. Each leader sends their first shred to relay 1, second shred to relay 2, and so on. If all goes well, each relay will receive shreds from all leaders.

3. After a timeout, relays send signed IHAVE messages to a single consensus leader, indicating the shreds they've received.

4. The consensus leader then constructs a block containing these IHAVE messages; if it doesn't include a sufficient proportion of IHAVE messages, the block will be invalid.

5. The consensus leader broadcasts this block to validators, who begin reaching consensus on the block.

This approach satisfies the binding and blinding properties with high probability and has good wallclock fairness, though more optimal solutions may emerge in the future.

Conclusion

The creation goal of Solana is to surpass NASDAQ. To achieve this, we must provide better prices than NASDAQ. To do this, we must empower applications with the ability to prioritize and cancel operations before execution. To give applications this capability, we must prevent leaders from unilaterally censoring orders. And to accomplish this, we must introduce multiple parallel leaders.