Always feeling like the next round will turn things around, precisely because we mistakenly take the group average as an individual's destiny. Imagine you start with 1000 dollars in an initial coin toss challenge, and you can choose to keep playing:

Toss a coin each round,

- Heads, wealth increases by 80%.

- Tails, wealth decreases by 50%.

Sounds like a game you can't lose!

But the reality is...

If 100,000 players participate in this game and each plays 100 rounds, you'll find: their average wealth is indeed growing exponentially, but the vast majority end up with less than 72 dollars, or even go bankrupt!

Why is the average wealth growing, but most people are getting poorer?

This is a typical non-ergodic trap. Always feeling like the next round will turn things around, precisely because we mistakenly take the group average as an individual's destiny.

Non-Ergodic Trap: Long-Term Average ≠ Your Real Destiny

What is ergodicity?

The concept of ergodicity first appeared in statistical physics and has profound implications in probability theory, finance, behavioral science, and machine learning. Its core question is: Does the long-term average apply to individuals? When making decisions, should we believe in the 'long-term average' or the 'reality of each experience'?

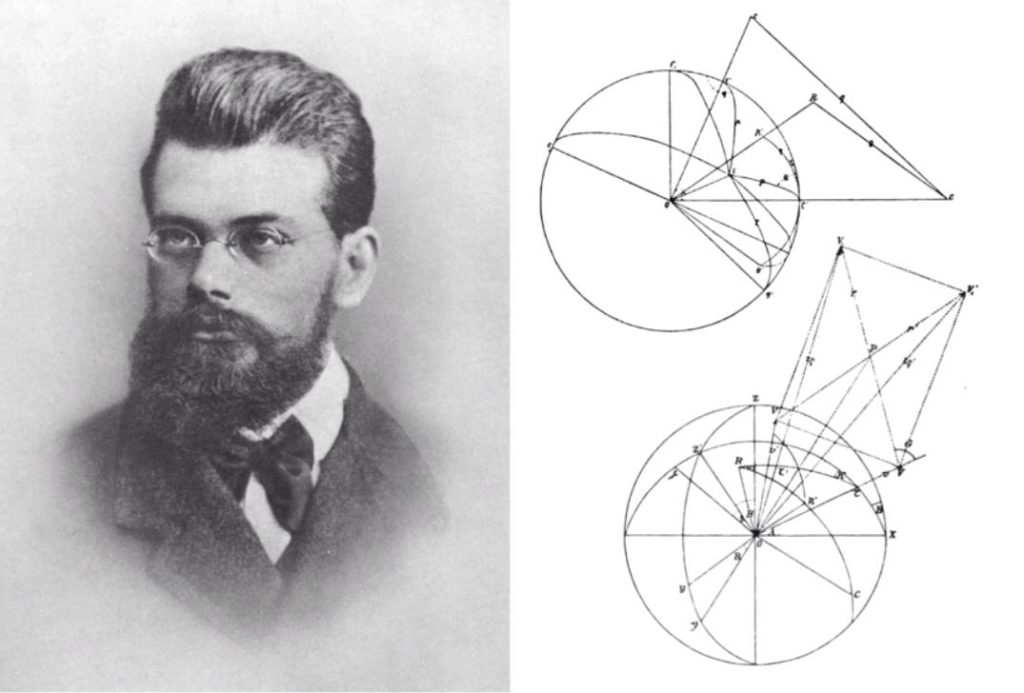

In the 19th century, physicist Ludwig Boltzmann proposed the ergodic hypothesis while studying gas molecule movement: if a gas molecule is observed long enough, it will traverse all possible states.

Imagine a closed gas container with countless gas molecules, each experiencing different velocity trajectories during collisions. The long-term trajectory of a single molecule is the same as the statistical distribution of the entire gas, meaning we can predict a single molecule's long-term trajectory from the state of all molecules at a given moment.

This is Boltzmann's famous ergodic hypothesis.

Mathematically, ergodicity means:

The left side is time average: describing the average result of an individual experiencing the same process multiple times over a sufficiently long period;

The right side is group average: describing the statistical expectation from observing numerous individuals at a given moment. In other words, when the system satisfies ergodic conditions, an individual's performance will ultimately converge to the group's "long-term average".

In an ergodic world, everyone's wealth would eventually approach the society's average wealth level. In an ergodic world, everyone would experience all possible economic states (wealth, poverty, success, failure), and individual destinies would converge to the group's "long-term average".

But real life is often non-ergodic: individuals have limited resources and often exit before experiencing all possible paths due to a single failure.

We often hear such misleading statements:

"The average annual income in a certain industry is over a million."

"Someone achieved financial freedom at 30, starting a business that took only two years."

"A certain index fund has high long-term annualized returns; just persist, and you'll become rich."

...

These seemingly reasonable statistical data appear to tell us an absolute truth. It seems that as long as you act, long-term average returns will apply to individuals. But these cases involve path dependence and non-replicable non-ergodic processes. Imitators cannot experience the same historical background, network of relationships, luck nodes, and are unaware of the number of hidden failures.

The data tells you the group's long-term average, but reality is full of short-term "cliff-like failures".

This is the most insidious trap of non-ergodicity —— Big data's statistical average ≠ Individual's real destiny.

One collapse might be irreparable for an individual, one failure could completely eliminate them from returning to the "average state". Each of us can only experience our life path once, unlike a casino that can average out probabilities across numerous gamblers.

Why Do Individual Long-Term Fates Often Fare Worse Than the "Average"?

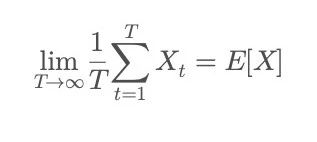

In non-ergodic systems, individual long-term performance often falls below the group average. This is not coincidental, but a systematic structural feature. The glossy average is often pulled up by the rare stories of entrepreneurial success, investment windfalls, and dramatic turnarounds, while the failures of most people never enter the statistics. Real-world systems are mostly multiplicative and path-dependent - such as investment compound interest, health deterioration, and reputation damage. Typical characteristics of such systems are: limited upside, but bottomless downside. One bankruptcy can ruin a lifetime; One wrong decision can completely change fate; One breach of trust can totally destroy credibility; Yet the wealth earned, performance gained, and advantages built are always limited. This is why in mathematics, the long-term growth rate of multiplicative processes is not equal to the "average return", but closer to: [Mathematical formula image] In comparison, group averages typically use arithmetic means, [Mathematical formula image] Due to the logarithmic function being a strictly concave function, based on Jensen's inequality, [Mathematical formula image] Therefore, the long-term growth rate of multiplicative systems (geometric mean) is always less than the arithmetic mean. The greater the volatility, the more obvious this difference. Arithmetic mean tells you 'what if you're always lucky', while geometric mean tells you 'how much you have left after weathering real-world storms'. This means individual long-term performance is always far below the "group average return" - not due to bad luck, but due to structural reasons.How to Make Optimal Decisions? The Kelly Criterion's Golden Ratio

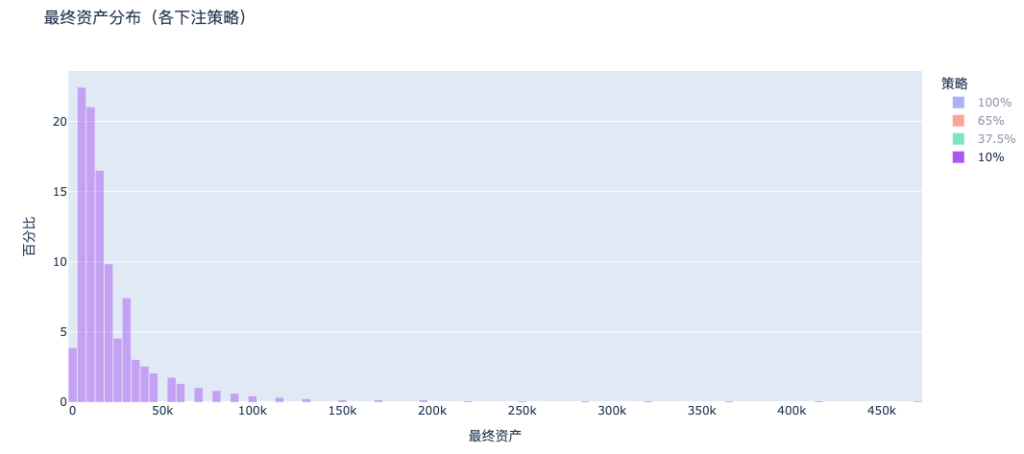

So what can we do in life's decisions to avoid a zero-sum fate in long-term games? How can we avoid bankruptcy while achieving long-term compound growth? The answer is: Never go All In, learn the Kelly bet! [Rest of the text continues in the same translated manner]

Without a bankruptcy distribution peak similar to an all-in situation, overall wealth is concentrated in the low-asset area. In comparison, 37.5% of strategies will pull out a clear long tail on the right side, achieving asset multiplication.

Kelly betting is the only strategy that considers both "not going bankrupt in most cases" and "significant appreciation", which is the mathematically optimal long-term survival strategy. This is the essence of the Kelly formula: it's not about winning the most, but ensuring you can survive long enough.

Life Philosophy in the Kelly Formula

The Kelly formula tells us that the secret to long-term success is learning to control the proportion of "betting". Life is not about who can land a single critical hit, but about who can keep playing.

In one's career, it's not about quitting impulsively or staying in a comfort zone, but continuously laying out plans, improving capabilities, daring to change lanes, and keeping options open;

In investing, it's not about going all in for sudden wealth, but controlling positions based on odds and preserving chips;

In relationships, it's not about investing all emotions and values in one person, but investing while maintaining self;

In growth and self-discipline, it's not about achieving change through a single burst, but by steadily and compoundedly optimizing life's structure.

Life is like a long game where your goal is not to win once, but to ensure you can keep playing. As long as you don't get eliminated, good things will happen.