Author: Max Wong @IOSG

Three years ago, we wrote an article about Appchain, which was prompted by dYdX's announcement that it was migrating its decentralized derivatives protocol from StarkEx L2 to the Cosmos chain, launching its v4 version as an independent blockchain based on the Cosmos SDK and Tendermint consensus.

In 2022, Appchain was perhaps a relatively marginal technology option. However, by 2025, with the launch of more and more Appchains, particularly Unichain and HyperEVM, the competitive landscape is subtly shifting, and trends are emerging around Appchain. This article will begin from this point and discuss our Appchain Thesis.

Choosing between Uniswap and Hyperliquid

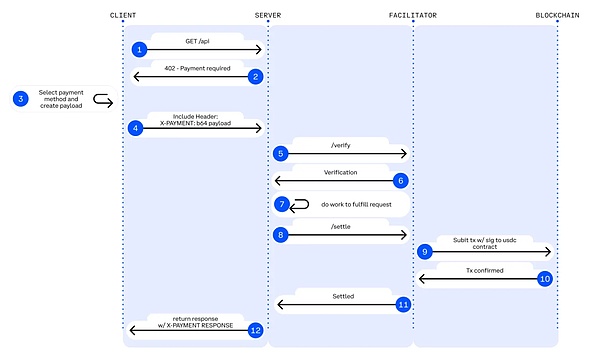

▲ Source: Unichain

The concept of Unichain emerged quite early. In 2022, Nascent founder Dan Elitzer published "The Inevitability of UNIchain," arguing that Uniswap's size, brand, liquidity structure, and need for performance and value capture pointed to the inevitability of launching Unichain. Discussions about Unichain have continued since then.

Unichain officially launched in February of this year, and over 100 application and infrastructure providers have already built on it. Currently, its TVL (Transaction Value Limit) is approximately $1 billion, ranking among the top five L2 blockchains. Future plans include the launch of Flashblocks with a 200ms block time and the Unichain verification network.

▲ Source: DeFiLlama

As a PERP, Hyperliquid clearly had a need for Appchain and deep customization from day 1. In addition to its core product, Hyperliquid also launched HyperEVM, which, like HyperCore, is protected by the HyperBFT consensus mechanism.

In other words, beyond its powerful PERP product, Hyperliquid is also exploring the possibility of building an ecosystem. Currently, the HyperEVM ecosystem has a TVL exceeding $2 billion, and ecosystem projects are beginning to emerge.

From the development of Unichain and HyperEVM, we can clearly see two points:

The L1/L2 competitive landscape is beginning to diverge. The combined TVL of the Unichain and HyperEVM ecosystems exceeds $3 billion. These assets should have been deposited on general-purpose L1/L2 platforms like Ethereum and Arbitrum. The departure of top-tier applications has directly led to the loss of core value sources such as TVL, transaction volume, transaction fees, and MEVs from these platforms.

In the past, L1/L2 blockchains had a symbiotic relationship with applications like Uniswap and Hyperliquid; the applications brought activity and users to the platforms, while the platforms provided security and infrastructure for the applications. Now, Unichain and HyperEVM have become platform layers themselves, directly competing with other L1/L2 blockchains. They are not only vying for users and liquidity but also for developers, inviting other projects to build on their chains, which has significantly altered the competitive landscape.

The expansion paths of Unichain and HyperEVM are drastically different from those of current L1/L2 systems. The latter typically build infrastructure first and then attract developers with incentives. Unichain and HyperEVM, however, follow a "product-first" model—they first have a core product that has been validated by the market, has a large user base, and enjoys brand recognition, and then build an ecosystem and network effects around that product.

This approach is more efficient and sustainable. It doesn't require "buying" the ecosystem through high developer incentives; instead, it attracts the ecosystem through the network effects and technological advantages of its core products. Developers choose to build on HyperEVM because of the presence of high-frequency trading users and real-world demand scenarios, not because of vague promises of incentives. Clearly, this is a more organic and sustainable growth model.

What has changed in the past three years?

▲ Source: zeeve

First, there's the maturity of the technology stack and the improvement of third-party service providers. Three years ago, building an Appchain required teams to master the entire blockchain technology stack. However, with the development and maturity of RaaS services such as OP Stack, Arbitrum Orbit, and AltLayer, developers can combine various modules on demand, much like choosing cloud services, from execution and data availability to settlement and interoperability. This greatly reduces the engineering complexity and upfront capital investment required to build an Appchain. The operating model has shifted from self-built infrastructure to purchasing services, providing flexibility and feasibility for application-layer innovation.

Secondly, there's brand and user mindshare. We all know attention is a scarce resource. Users tend to be loyal to an application's brand, not the underlying technology: users use Uniswap because of its product experience, not because it runs on Ethereum. With the widespread adoption of multi-chain wallets and further improvements in UX, users are almost unaware of using different chains—their touchpoints are often primarily the wallet and the application. And when an application builds its own chain, users' assets, identity, and usage habits are all embedded within the application's ecosystem, forming a powerful network effect.

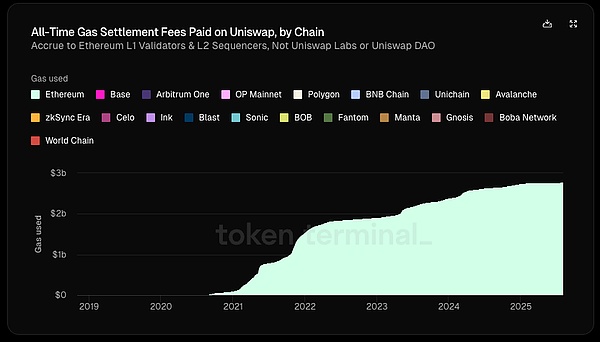

▲ Source: Token Terminal

Most importantly, the pursuit of economic sovereignty by applications is gradually becoming more prominent. In the traditional L1/L2 architecture, we can see that value flow exhibits a clear "top-down" trend:

Value is created at the application layer (Uniswap transactions, Aave lending).

Users pay fees for using the application (application fees + gas fee), a portion of which goes to the protocol and a portion to the LP or other participants.

100% of the gas fees go to either the L1 validator or the L2 sorter.

MEV is divided among searchers, builders, and validators in different proportions.

Ultimately, L1 tokens capture value beyond app fees through staking.

In this chain, the application layer, which creates the most value, actually captures the least.

According to Token Terminal statistics, of Uniswap's total value creation of $6.4 billion (including LP rewards, gas fees, etc.), the protocol/developers, equity investors, and token holders received less than 1%. Since its launch, Uniswap has generated $2.7 billion in gas revenue for Ethereum, which is approximately 20% of Ethereum's settlement fees.

But what if the application has its own chain?

They can collect gas fees for themselves, using their own tokens as gas tokens; and internalize MEVs, minimizing malicious MEVs by controlling the sorter and returning beneficial MEVs to users; or customize fee models to achieve more complex fee structures, etc.

From this perspective, seeking the internalization of value becomes the ideal choice for applications. When an application has sufficient bargaining power, it will naturally demand more economic benefits. Therefore, high-quality applications have a weak dependency on the underlying blockchain, while the underlying blockchain has a strong dependency on high-quality applications.

summary

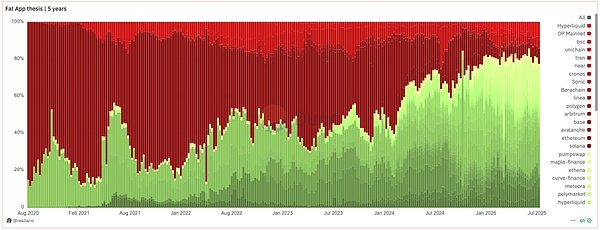

▲ Source: Dune@reallario

The chart above roughly compares the revenue of protocols (red) and applications (green) from 2020 to the present. We can clearly see that the value captured by applications is gradually increasing, reaching approximately 80% this year. This may, to some extent, overturn Joel Monegro's famous theory of "fat protocols, thin applications".

We are witnessing a paradigm shift from the "fat protocol" theory to the "fat application" theory. Looking back at the pricing logic of projects in the crypto space, it has primarily revolved around "technical breakthroughs" and the development of underlying infrastructure. In the future, this will gradually shift towards pricing methods anchored to brand, traffic, and value capture capabilities. If applications can easily build their own chains based on modular services, the traditional "rent-collecting" model of L1 will be challenged. Just as the rise of SaaS reduced the bargaining power of traditional software giants, the maturity of modular infrastructure is also weakening the monopoly of L1.

In the future, the market capitalization of leading applications will undoubtedly exceed that of most L1 applications. The valuation logic for L1 will shift from the previous "capturing the total value of the ecosystem" to a stable, secure, decentralized "infrastructure service provider." Its valuation logic will be closer to that of public goods that generate stable cash flow, rather than "monopolistic" giants that can capture most of the ecosystem value. Its valuation bubble will be squeezed to some extent. L1 also needs to rethink its own positioning.

Regarding Appchain, our view is that, due to its brand recognition, user mindshare, and highly customizable on-chain capabilities, Appchain can better accumulate long-term user value. In the era of "fat apps," these apps can not only capture the direct value they create, but also build blockchains around themselves, further externalizing and capturing the value of the infrastructure—they are both products and platforms; serving both end users and other developers. Beyond economic sovereignty, top-tier apps will also seek other forms of sovereignty: the right to decide on protocol upgrades, transaction ordering and censorship resistance, and ownership of user data, among others.

This article primarily discusses the topic within the context of top-tier applications like Uniswap and Hyperliquid, which have already launched Appchains. Appchain development is still in its early stages (Uniswap's TVL still accounts for 71.4% on Ethereum). Protocols like Aave, which involve asset packaging and collateral and heavily rely on on-chain composability, are also less suitable for Appchains. Comparatively, PERP, which only requires oracles for external access, is a better fit for Appchains. Furthermore, Appchains are not the optimal choice for mid-tier applications and require case-by-case analysis. This will not be elaborated upon further here.