Author: Kalle Rosenbaum & Linnéa Rosenbaum

Source: https://bitcoindevphilosophy.com/#adversarialthinking

This chapter discusses " adversarial thinking," a mindset that focuses on where things might go wrong and how adversaries might act. We begin by discussing Bitcoin's security assumptions and security models. Then, we explain how ordinary users can enhance their autonomy and the decentralization of Bitcoin's full nodes—this time through the lens of adversarial thinking. Next, we examine the actual threats to Bitcoin and the thinking of adversaries. Finally, we discuss the " axion of resistance," which can help you understand the starting point for those who developed Bitcoin.

When discussing the security of various systems, it's crucial to understand their security assumptions. In Bitcoin, a typical security assumption is that "discrete algorithmic problems are intractable," meaning that, simply put, it's practically impossible to find the private key behind a given public key. Another very strong security assumption is that the majority of the network's hash power is honest, meaning they will follow the rules. If these assumptions prove wrong, Bitcoin is in trouble.

In 2015, Andrew Poelstra gave a presentation at the Scaling Bitcoin conference in Hong Kong, analyzing Bitcoin's security assumptions. He first pointed out that many systems more or less ignore hostile acts; for example, protecting a building against all types of hostile incidents is extremely difficult. Instead, we generally accept that there is a certain probability that someone might want to burn down the house, and then, through legal enforcement and other measures, we can prevent such incidents and other hostile acts to some extent.

But things are a little different on the internet:

However, on the internet, we don't have such measures available. In a pseudonym and anonymous system, anyone can connect to anyone else and potentially harm the system. If it's possible to intentionally harm the entire system, then someone will do it. We cannot assume that such people are all in the open and can be apprehended.

— Andrew Poelstra, "Security Assumptions," Scaling Bitcoin Hong Kong (2015)

As a result, all of Bitcoin's known weaknesses must be addressed to some extent, or they will be exploited. After all, Bitcoin has become the world's largest "honeypot."

Poelstra then explained why Bitcoin is a new system; it is more elusive than (for example) signature protocols with explicit security assumptions.

Jemeson Lopp discussed this in detail on his personal blog:

In fact, the Bitcoin protocol was, and still is, built on an undefined standard (or security model). The best we can do is study the incentives and actions of the actors within the system in order to better understand and attempt to describe them.

— Jameson Lopp, *Security Models of Bitcoin: An In-Depth Study* (2016)

Therefore, the system we are using appears to work in a real-world environment, but I cannot formally prove its security. Perhaps, due to the system's inherent complexity, such evidence is simply unavailable.

6.1 Not only useful for Bitcoin experts

Adversarial thinking is useful not only for hardcore Bitcoin developers and experts, but also for ordinary Bitcoin users. Ragnar Lifthasir mentioned in a Twitter threads that overly simplistic interpretations of Bitcoin—such as "you just need to hoard it"—may devalue Bitcoin itself; his conclusion is:

To make both Bitcoin and ourselves stronger, we need to think like the software engineers who contribute code to Bitcoin. They review each other's work, meticulously searching for bugs. In their technical activities, they discuss all the possible scenarios in which a proposal might fail. They think adversarially; they are conservative.

— Ragnar Lifthasir, Twitter (2020)

He calls these oversimplified interpretations paranoia. What he's trying to say is that there's a danger in this—if you focus on just one thing, say, "just hoard coins," you might overlook other things that are arguably more important, such as safely storing your Bitcoin and using it in a trustless manner as much as possible.

6.2 Threats

Bitcoin has many known weaknesses, and many of them are being actively justified. To get a basic impression, we can look at the "Weaknesses" page on the Bitcoin Wiki. This page lists many issues, such as wallet theft and denial-of-service attacks.

If an attacker spreads their controlled clients across the entire network, your full node could connect to only nodes controlled by that attacker. While Bitcoin never uses node statistics to determine anything, completely isolating a node from a network of honest nodes can greatly facilitate other attacks.

— Multiple authors, Bitcoin Wiki

This type of attack is called a " Sybil attack ." Its basic form is that an entity controls multiple nodes in a network and pretends to be multiple entities.

(Translator's note: The common translation of "Sybil attack" is "witch attack," but "clone attack" is actually a more accurate translation. This translation will be used below.)

As mentioned in the preceding quote, clone attacks are not effective in the Bitcoin network because there is no voting based on the number of nodes or other countable entities, but only on computing power (i.e., mining, see Chapter 1.1 ) ( Chinese translation ). However, this flat structure makes the system vulnerable to other attacks. The "Vulnerabilities" page lists other possible attacks, such as information hiding (often called an "eclipse attack "), and also lists heuristics implemented Bitcoin Core software to counter such attacks.

This is an example of a real threat that needs to be considered.

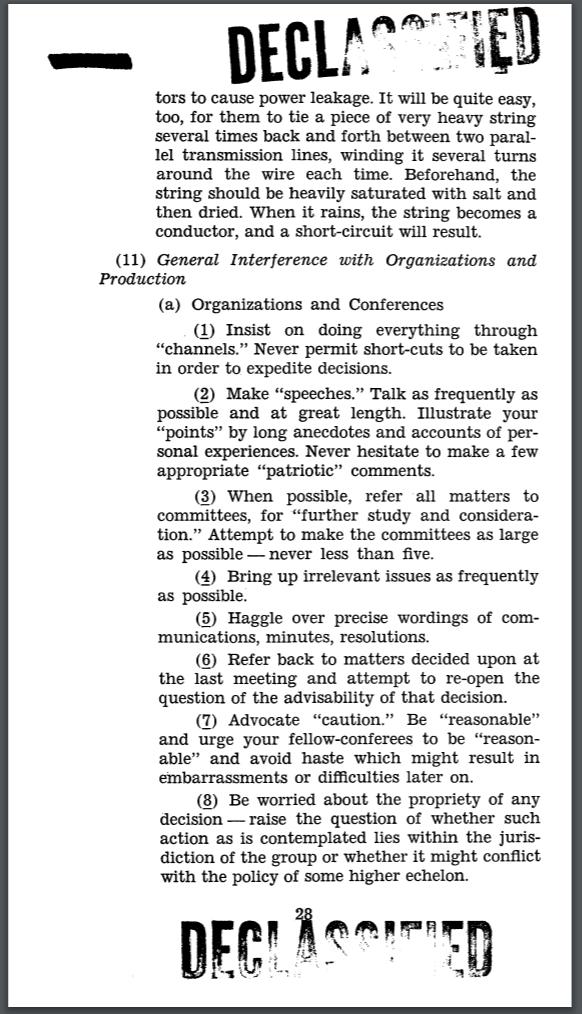

To better understand the mindset of an adversary, it might be helpful to understand how they operate. There was a U.S. government agency called the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which operated during World War II. One of its purposes was espionage, sabotage, and propaganda. The agency produced a pamphlet for its staff, teaching them how to carry out sabotage. This pamphlet, titled "The Simple Sabotage Field Manual," contained specific suggestions for infiltrating the enemy and hindering their operations. These suggestions ranged from burning down warehouses to sharpening drill bits, all aimed at reducing the efficiency of enemy forces.

- Figure 6. Excerpt from *The Handbook of Simple Destruction* -

For example, this chapter (Figure 6) discusses how an infiltrator can dismantle an enemy organization. It's easy to imagine that such strategies could also be used against the Bitcoin development process (see Chapter 7 ), which is open to everyone. A deliberate attacker could delay development by endlessly expressing irrelevant concerns, nitpicking wording, and rehashing fully resolved discussions. Attackers could also hire cyber swarms to increase efficiency; we can call this a "social swarm attack." Using a social swarm attack, an attacker can make the opposition to a proposed change appear much greater than the actual opposition.

You see, a resolute nation can and will indeed use all its power to destroy its enemies, including dismantling them from within. Because Bitcoin is a currency that competes with existing fiat currencies, some countries may view Bitcoin as an enemy.

Eric Voskuil discusses what he calls the "resistance axiom" on his "Cryptoeconomics Wiki" page :

In other words, there is an assumption here that systems capable of resisting state control are possible. Because empirical studies of behavior in similar systems do not treat this as a fact, but only as a plausible assumption.

If you don't accept the axiom of resistance, you're thinking about a completely different system than Bitcoin . If you assume no system can resist state control, then your conclusions are meaningless in the context of Bitcoin—just as the conclusions of spherical geometry and Euclidean geometry contradict each other. Without this axiom, how can Bitcoin be trustless and censorship-resistant? This contradiction leads to obvious errors when trying to rationalize conflicts.

——Eric Voskuil, Cryptoeconomics Wiki (2017)

What he really meant was that it only makes sense to try when people assume it's possible to create systems that the state can't control.

This means that if you want to develop on Bitcoin, you should accept this axiom; otherwise, you'd be better off spending your time on other projects. Knowing this axiom can help you focus your energy on the real problem at hand: writing your code around a nation-state adversary. In other words, adversarial thinking.

6.3 Conclusion

A decentralized low-pass system cannot be auditable outside the system itself; therefore, Bitcoin must be more vigilant against malicious activity than traditional systems. Adversarial thinking is essential in such a system.

To ensure Bitcoin's security, you need to understand its adversaries and their incentives. Most threats seem to stem from nation-states with strong economies, who have tax revenue and the ability to print money. They are unlikely to easily relinquish their privilege of printing currency.