Author: Kalle Rosenbaum & Linnéa Rosenbaum

In this chapter, we will explore how Bitcoin can scale and what methods cannot. We'll begin by examining how people have previously thought about this issue. The main body of this chapter then explains the various methods for increasing Bitcoin's throughput, specifically vertical scaling, horizontal scaling, inward scaling, and tiered scaling. Each method will be discussed afterward to see if it conflicts with Bitcoin's value proposition.

In the Bitcoin world, the term "scaling" is often used in different senses. Some believe it refers to increased blockchain transaction throughput, others think it means using the blockchain more efficiently, and still others believe it refers to developing systems built on top of Bitcoin.

In the context of Bitcoin, and for the purposes of this book, we define "scaling" as " increasing the available throughput of Bitcoin without sacrificing its censorship resistance ." This definition encompasses several changes, such as:

- Make transaction inputs use fewer bytes

- Improve the efficiency of signature verification

- Allow Bitcoin's peer-to-peer network to use less bandwidth

- Batch Transaction Processing

- Layered architecture

We will soon delve into various methods of scaling, but first, let's begin with a brief overview of Bitcoin's history from a scaling perspective.

8.1 History

Scaling has been a focal point of discussion since the inception of Bitcoin. The very first paragraph of the reply to the Cryptography mailing list that sent Satoshi Nakamoto announcing the Bitcoin white paper is about scaling:

Satoshi Nakamoto wrote:

> I've been working on a new electronic cash system that's fully

> peer-to-peer, with no trusted third party.

>

The paper is available at:

http://www.bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdfWe desperately need such a system, but based on my understanding of your proposal, it seems impossible to scale to the required size.

— James A. Donald's reply to Satoshi Nakamoto, Cryptography mailing list (2018)

This discussion may not be very interesting or accurate in itself, but it shows that scaling has been a concern from the very beginning.

The discussion about scaling peaked between 2015 and 2017, when many different ideas circulated about whether to increase the maximum size limit of Bitcoin blocks. This was a rather tedious debate about whether to change a parameter in the source code. Such a change wouldn't fundamentally solve any problems; it would only postpone the scaling issue for a while, essentially accumulating "technical debt."

In 2015, a conference called " Scaling Bitcoin " was held in Montreal; six months later, a follow-up conference was held in Hong Kong; and subsequently, a series of conferences were held around the world. The focus of the Scaling Bitcoin conferences was entirely on solving the scaling problem. Many Bitcoin developers and enthusiasts gathered at these conferences to discuss a wide variety of scaling issues and proposals. The vast majority of discussions did not fall into the cliché of increasing the block size limit, but rather focused on longer-term solutions.

Following the Hong Kong conference in December 2015, Gregory Maxwell summarized his views on many of the issues discussed , but his starting point was a broader philosophy of expansion.

There is a fundamental contradiction between scalability and decentralization in currently available technologies. If the cost of using the Bitcoin system becomes too high, people will be forced to trust third parties instead of independently enforcing the system's rules. If the resource consumption of the Bitcoin blockchain is too large relative to available technology, Bitcoin will lose its competitive advantage over traditional systems because the verification cost becomes too high (displacing many users), thus forcing the system to reintroduce trust factors. If throughput is too low and our methods of constructing transactions are too inefficient, the cost of accessing the blockchain to resolve disputes will become too high, also pushing trust factors into the system.

— Gregory Maxwell, "Improving Throughput in the Bitcoin System" (2015)

He was talking about the trade-off between throughput and decentralization. If you allow larger blocks, some will be pushed off the network because they don't have enough computing resources to validate the expanded blocks. But on the other hand, if using block space becomes more expensive, fewer people can afford to use it as a dispute resolution mechanism. In either case, users will be pushed towards services that require trust.

He then summarized the many scaling methods that emerged at the conference, including: computationally more efficient signature verification, " Segregated Witness " which incorporates block size changes, a more space-efficient block propagation mechanism, and the development of a layered protocol on Bitcoin. Since then, many of these methods have been implemented.

8.2 Expansion Methods

As mentioned earlier, increasing Bitcoin's throughput does not necessarily require raising the block size limit or other restrictions. Now, we will list common methods for scaling, some of which are not constrained by the throughput-decentralization contradiction mentioned in the previous section.

8.2.1 Vertical Expansion

"Vertical scaling" refers to increasing the computing resources of machines that process data. In the context of Bitcoin, such machines are full nodes, which are machines that verify the blockchain on behalf of users.

In the Bitcoin world, the most discussed vertical scaling technique is increasing the block size limit. This requires some full nodes to upgrade their hardware to keep up with the increased computational demands. The drawback of this approach is that it comes at the cost of centralization, as we have discussed in previous chapters; a more in-depth discussion can be found in Chapter 1.2 ( Chinese translation ).

Besides negatively impacting "full node decentralization," vertical scaling may also negatively affect Bitcoin's "miner decentralization" (see Chapter 1.1 ( Chinese translation ) for a detailed explanation) and security, albeit in a more subtle way. Let's first look at how miners "should" operate. Suppose a miner mines a block at height 7 and publishes it to the Bitcoin network; this block needs some time to gain widespread network acceptance for two reasons:

- Due to bandwidth limitations, it takes time for blocks to propagate between nodes.

- Validating blocks also takes time.

While this block is propagating through the network, many miners are still mining based on block 6 (i.e., still mining at block height 7) because they haven't received it yet and haven't verified it. If, during this period, one of these miners discovers a new block at block height 7, then two competing blocks will be formed at that height. Only one block at each height can be recognized by the entire network, meaning that one of these two candidate blocks must be discarded.

In short, such "stale blocks" appear on the network because each block takes time to propagate, and the longer the propagation time, the higher the probability of stale blocks appearing.

If the block size limit were removed, the average size of the actually mined blocks would increase significantly, which would slow down the propagation speed of blocks in the network (due to bandwidth limitations and verification time). This increased propagation time would also increase the probability of stale blocks appearing.

Miners certainly don't want their blocks to become stale blocks; it's like a cooked duck flying away. Therefore, they will definitely try to avoid this situation. Measures they can take include:

- Delaying the verification of incoming blocks is also called "validationless mining " (discussed further in section 9.2.4.4 ). Miners can check only the proof-of-work in the block header and then continue mining until the complete block is downloaded, at which point they can verify it.

- Connect to a mining pool with higher bandwidth and a more stable connection.

Unverified mining further reduces the decentralization of full nodes because miners directly trust incoming blocks—at least temporarily. It also more or less harms security because a certain percentage of mining power may be used on an invalid blockchain instead of being used to build the most robust and effective blockchain.

The second point above also has a negative impact on miner decentralization, see Chapter 1.1 ( Chinese translation ) for details, because generally speaking, the mining pool with the most stable connection and the largest bandwidth is the largest mining pool, which causes miners to gradually gather into a few mining pools.

8.2.2 Horizontal Expansion

"Horizontal scaling" refers to the technique of distributing workloads across multiple machines. While this is a common scaling method for popular websites and databases, it is not easy to implement on Bitcoin.

Many people refer to this Bitcoin scaling method as " sharding ." Essentially, it means that each full node only verifies a portion of the blockchain. Peter Todd has devoted considerable time to this concept. He wrote a blog post explaining sharding in a broader sense and also proposed his own idea called " treechains ." The article is quite difficult to read, but some of Todd's points are very easy to understand.

In a sharded system, "full node barriers" cannot function, or at least not directly. The fundamental reason is that not everyone holds all the data, so you must determine what happened when not all the data is available.

— Peter Todd, "Why Sharding is So Difficult to Scale Bitcoin" (2015)

He then presented many ideas regarding handling sharding (or horizontal scaling). At the end of the article, he concluded:

But there's a major problem: Good heavens! XXX is far more complex than Bitcoin! Even a "compact" version of sharding—my linearized solution, without using zk-SNARKs zero-knowledge proofs—is still one to two orders of magnitude more complex than the currently used Bitcoin protocol; and now, many companies in the industry seem to have stopped using the Bitcoin protocol directly and instead use centralized API providers. Implementing the above solution and delivering it to end users will not be a simple task.

On the other hand, decentralization is not cheap: using PayPal is one to two orders of magnitude simpler than using the Bitcoin protocol.

— Peter Todd, "Why Sharding is So Difficult to Scale Bitcoin" (2015)

His conclusion was that sharding might be technically feasible, but it would add a significant amount of complexity to the system. Given that many users already find Bitcoin too complex and prefer centralized services, convincing them to use something more complex would be difficult.

8.3 Internal Expansion

Although horizontal and vertical scaling have proven highly effective in centralized systems such as databases and internet servers, they seem unsuitable for decentralized systems like Bitcoin due to their centralized effects.

A much less-noticed approach can be called "inward scaling," which means "doing more with less." It refers to the ongoing work of many developers: optimizing the performance of algorithms already in use so that we can do better within the existing limitations of the system.

The improvements achieved through scaling inwards are astonishing—and that's no exaggeration. To give you a basic idea of the improvements over the years, Jameson Lopp ran benchmark tests for blockchain synchronization, comparing Bitcoin Core versions since 0.8.

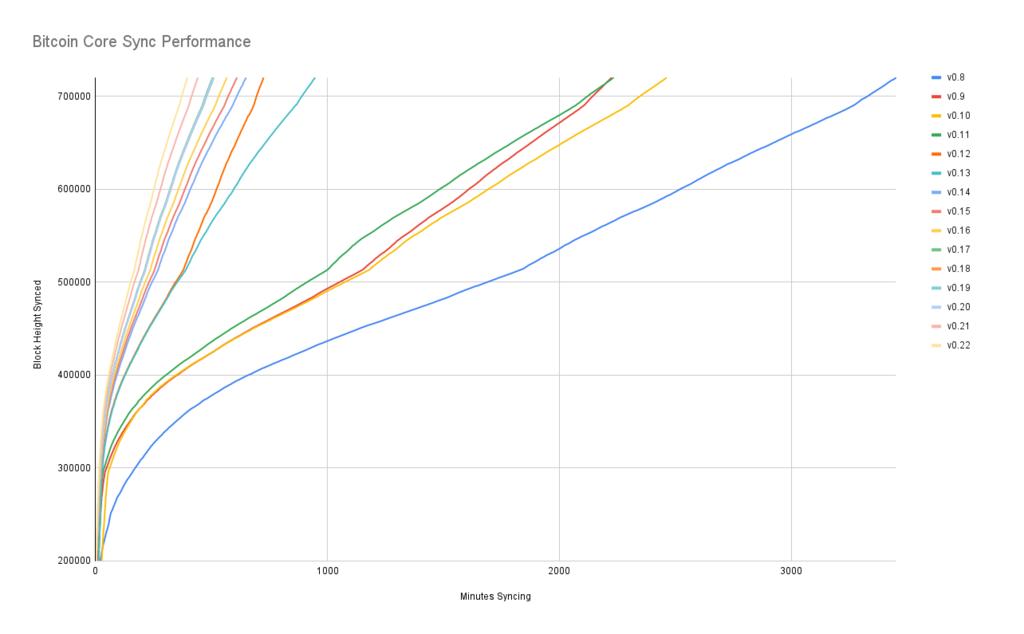

Figure 7. Performance of initial block download across multiple versions of `Bitcoin Core`. The Y-axis represents the block height to which synchronization is performed, and the X-axis represents the time taken to synchronize to that height.

The different colored lines represent different versions of Bitcoin Core . The leftmost line is the latest version, version 0.22, released in September 2021, which took 396 minutes to synchronize. The rightmost line is version 0.8, released in November 2013, which took 3452 minutes to synchronize. All these improvements—roughly a 10x performance increase—are achieved by scaling up internally.

These improvements can be categorized as saving space (memory, disk space, bandwidth, etc.) or saving computing power. Regardless of the type of improvement, they all contribute to the improvements shown in the diagram above.

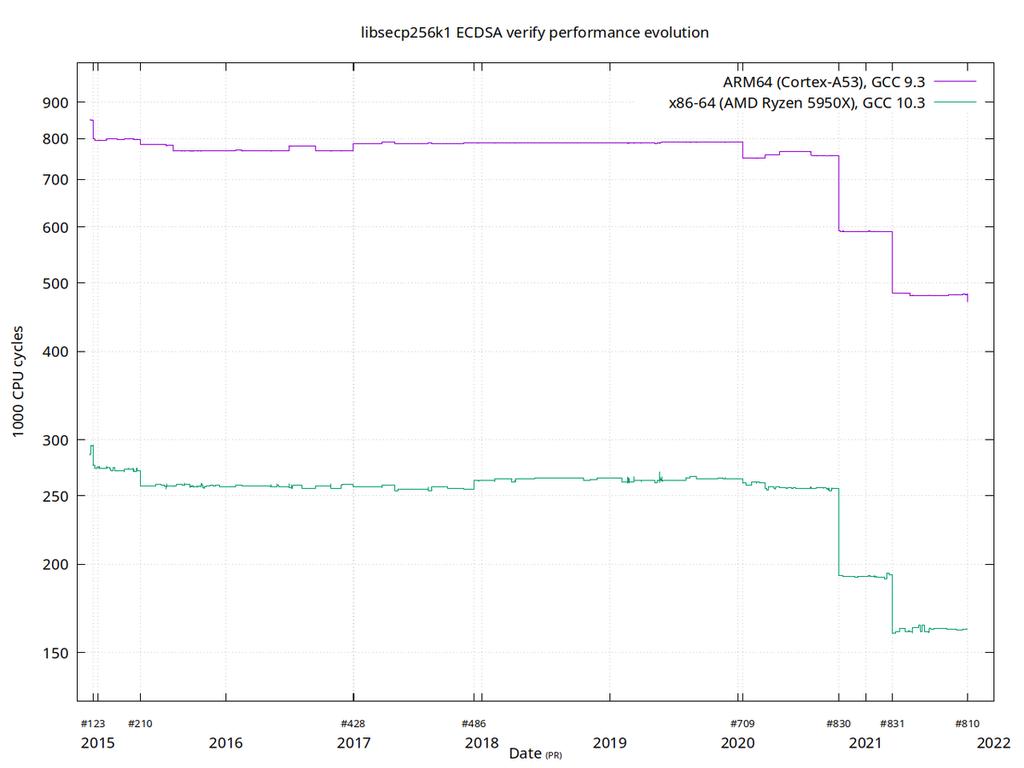

A good example of computational optimization is the libsecp256k1 library, which (and other parts) implements cryptographic primitives for generating and verifying digital signatures. Pieter Wuille, one of the contributors to this library, once tweeted a Twitter threads demonstrating how performance improvements were achieved across multiple pull requests.

Figure 8. How the performance of signature verification gradually improves; important PRs are marked on the X-axis.

The graph above illustrates the performance trends of signature verification on two types of 64-bit CPUs (ARM and x86). The performance difference between the two CPUs stems from the fact that the x86 architecture has more specialized instructions available, while the ARM architecture has fewer and more general instructions. However, the same trend emerges across both architectures. Note that the Y-axis is in logarithmic units, which diminishes the visual impact; the actual effect is much more surprising.

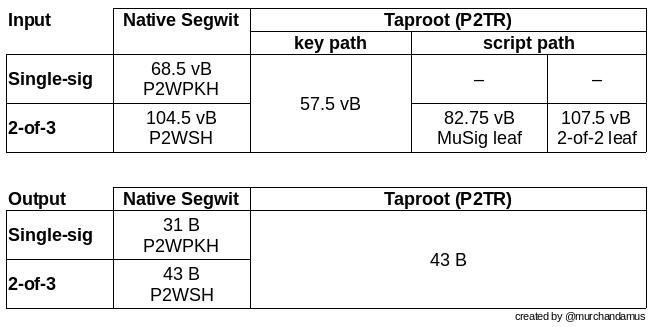

There are many other good examples of space-saving improvements. In a Medium blog post about how "Taproot" can help save space, Murch compares the block space occupied by various 2-of-3 threshold signature scripts; there are also several ways to implement 2-of-3 threshold signatures in a Taproot script.

Figure 9. Block space usage for different cost scripts; Taproot vs. more traditional script types.

A 2-of-3 threshold signature using the native Segregated Witness script requires a total of 104.5 + 43 vB = 147.5 vB (virtual bytes); while the most space-efficient Taproot script only requires 57.5 + 43 vB = 100.5 vB (in standard use cases). In the worst-case scenario, which is also rare, such as when a signer is unavailable for some reason, the Taproot script will use 107.5 + 43 vB = 150.5 vB. You don't need to understand all the details to see how the developers thought about space conservation—meticulous to the smallest detail.

Translator's Note: Taproot scripts can reduce transaction block space usage in many cases—but not in terms of raw bytes, but in "vB (virtual bytes)". After the Segregated Witness upgrade, different parts of a transaction (which can be simply divided into transaction body data and signature data) have a multiplier when calculating block space usage, which is the source of the vB unit. However, it's difficult to say that the change in the type of script used by the user helps improve the initialization synchronization speed shown in Figure 7 due to the reduction in transaction size, because the block size may not necessarily be reduced; it's more likely that the reduction comes primarily from the reduced verification computation burden of Segregated Witness and subsequent versions of the script.

Beyond scaling the Bitcoin software internally, there are many other ways for users to contribute to scaling. They can create transactions more intelligently, saving on transaction fees and reducing their reliance on full node resources. Two commonly used techniques aim at this goal: "transaction batching" and "output consolidation."

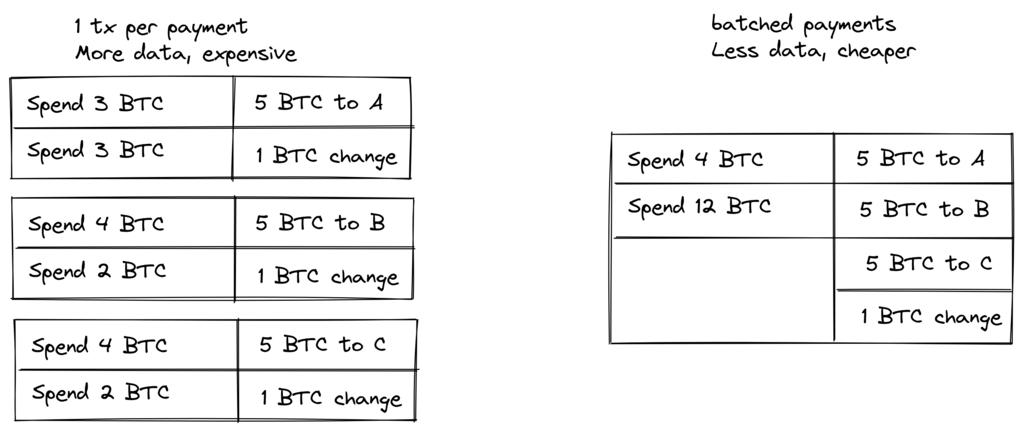

The idea behind transaction batching is to combine multiple payments into a single transaction, rather than making them separate transactions. This can save you a lot on transaction fees while reducing the amount of block space required.

Figure 10. Batch transaction processing combines multiple payments into a single transaction to save on transaction fees.

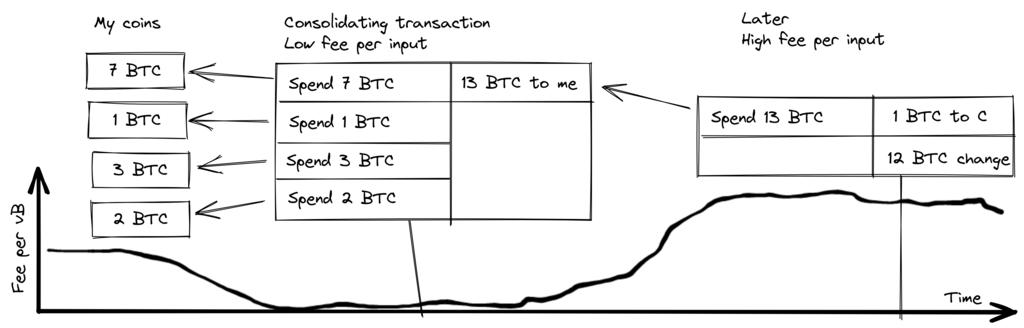

The idea behind output consolidation is to combine multiple transaction outputs into a single output during periods of lower block space demand. This can save you transaction fees later when you need to initiate transactions during periods of higher block space demand.

- Figure 11. Output Consolidation. When network transaction fees are low, mint your multiple coins into one to save on fees later.

The extent to which output consolidation constitutes internal scaling may not be immediately apparent. After all, the blockchain's data might increase slightly due to this method. However, the UTXO set—the database tracking which address owns which coin—will shrink if you spend more UTXOs than you create. This alleviates the burden on full nodes maintaining the UTXO set.

Unfortunately, both of these UTXO management techniques can compromise your or your recipients' privacy. In batch processing, each recipient will know that the batched input came from you, and each other output was given to a recipient (except for the change, which went to you). In UTXO consolidation, you'll discover that all the consolidated outputs came from the same wallet. You may have to make trade-offs between cost efficiency and privacy.

8.2.4 Tiered Expansion

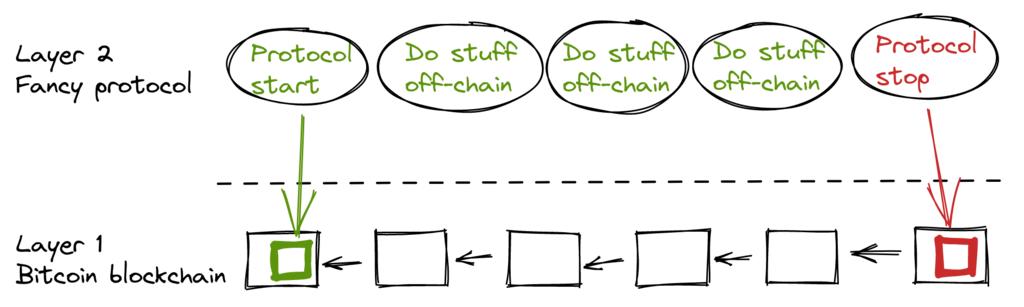

The most powerful scaling method is probably "layering". The idea behind layering is that a single protocol can settle payments between users without requiring a blockchain to confirm their transactions. This has been briefly discussed in Chapter 2 ( Chinese translation ) and Chapter 3.7 ( Chinese translation ).

The starting point of a layered protocol is that two or more people agree on a starting transaction and publish it to the blockchain network, as shown in Figure 12.

- Figure 12. A standard layer 2 protocol built on top of Bitcoin layer 1 -

The construction of this starting transaction varies depending on the protocol, but a common approach is for participants to first create a starting transaction to be signed, along with a series of pre-signed penalty transactions; these penalty transactions spend the output of the starting transaction in different ways. The starting transaction then collects all signatures and is broadcast to the blockchain, while the penalty transactions (held by individual users) receive all signatures and are published to the blockchain to punish misbehaving participants. This incentivizes all parties to keep their promises, thus achieving trustlessness in the protocol.

Once the initial transaction is confirmed in a block, the protocol can begin to function. For example, it can enable very fast payments between participants, implement privacy-preserving technologies, or enable more advanced scripting that the Bitcoin blockchain cannot support.

We won't go into detail about how each specific protocol works, but as you can see in Figure 12, the blockchain is rarely used throughout the entire lifecycle of the layered protocols. All the interesting actions occur off-chain . We've seen this potentially enhance privacy (if implemented correctly), but it also benefits scalability.

In a Reddit post titled "Getting to the Moon Requires Multistage Rockets or the Rocket Equation Will Eat Your Lunch... Putting All the Clown-like People on Catapults and Waiting for Success Is the Right Way to Do It," Gregory Maxwell explains why layering is the best way to increase Bitcoin throughput by several orders of magnitude.

He began by emphasizing that it was a mistake to consider Visa and Mastercard as Bitcoin's main competitors, and that increasing the block size limit was a flawed approach stemming from such fallacies. He then discussed how layering could truly transform the situation.

So, does this mean Bitcoin can't be the big winner in payment technology? No. It simply means that to achieve the throughput needed to serve the global payment needs, we must be smarter.

From the outset, Bitcoin was designed to securely combine various layers through its smart contract programming capabilities (what, you think this was just to allow people to hype up meaningless "Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs)" as a cosmic invention?). It's time we used the Bitcoin system as a highly accessible, fully trusted robotic judge, managing the vast majority of our businesses outside the courtroom—only, the way we transacted would determine that if anything went wrong, we would have all the evidence and established contracts to be confident that this robotic court would make the right decision. (Geek side note: If this seems impossible, please revisit this older article on transaction cut-through.)

This is possible because of Bitcoin's core properties. A censorable, reversible underlying system is not suitable for developing robust upper-layer transaction processing systems on top of it—moreover, if the underlying assets are unreliable, there is no point in using them for transactions.

—Gregory Maxwell, r/Bitcoin on Reddit (2016)

This judge's analogy vividly illustrates the working principle of layering: the judge must be incorruptible and not fickle; otherwise, the layers above the Bitcoin base layer will not function reliably.

He then offered his thoughts on centralized services. Generally speaking, there's nothing wrong with trusting a central server in order to use a negligible amount of Bitcoin: it's also a form of tiered scaling.

Since Maxwell wrote this article, many new layers have emerged, and his words remain true. The success of the Lightning Network proves that layering is the right way to improve the usefulness of Bitcoin.

8.3 Conclusion

We have discussed several proposed methods for scaling up Bitcoin (increasing the available throughput of Bitcoin). Scaling up has been one of the concerns surrounding Bitcoin from the very beginning.

Today, we know that Bitcoin cannot scale well vertically ("buying more advanced hardware") and horizontally ("verifying only a portion of the data"), but it can scale inward ("managing more with less") and hierarchically ("developing protocols on Bitcoin").