Author: Vaidik Mandloi

Original title: Tokenisation Is Moving Into the Core of Financial Markets

Compiled and edited by: BitpushNews

Last week, two decisions by U.S. regulators radically altered the landscape of tokenized assets in financial markets.

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission ( CFTC ) stated that Bitcoin, Ethereum, and USDC can now be used as collateral in regulated derivatives markets.

At almost the same time, the Securities and Exchange Commission ( SEC ) allowed the U.S. Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC) to test a tokenized settlement system without triggering enforcement action (i.e., a "no-action letter").

These decisions are not intended to promote cryptocurrencies, nor to make transactions easier for retail users. Regulators are more concerned with whether tokenized assets are sufficiently reliable in the risk management环节 (link/stage) of the financial system.

Collateral and settlement are core functions of finance.

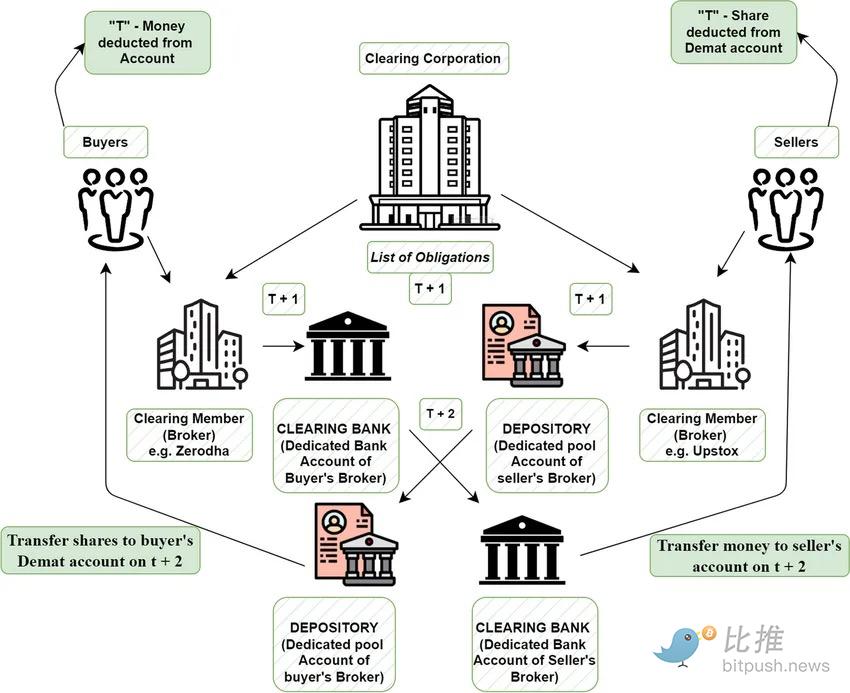

Margin is provided by collateral traders to cope with market volatility and cover potential losses; settlement is the process of completing a transaction and transferring funds. When an asset is approved for use in these areas, it means that regulators have confidence in its performance under pressure.

Previously, tokenized assets mostly operated outside of these core systems. They could be issued and traded, but failed to be incorporated into margin systems or settlement processes. This limited the practical development of tokenization.

The key development now is that regulators are beginning to allow tokenized assets into these core tiers.

This article will explain why we chose to start with collateral and settlement, the practical implications of the relevant approvals, and the new tokenization model that is emerging from this.

Why is collateral the preferred place for regulators to allow tokenization?

To understand why the CFTC's decisions are important, it is first necessary to understand the actual function of collateral in the derivatives market.

In the derivatives market, collateral does only one very specific job: locking it up before losses spread.

When traders open leveraged positions, the clearinghouse doesn't care about the logic of the trade; it only cares whether, if the position moves against it, the submitted collateral can be liquidated quickly enough at a known price to cover the losses. If liquidation fails, the losses don't stay with the trader but are transferred to the clearing member, then to the clearinghouse, and ultimately affect the entire market.

This is why collateral rules exist. They are designed to prevent forced liquidations from escalating into systemic funding gaps.

In practice, to qualify an asset as collateral, a clearinghouse will assess four dimensions:

Liquidity: Is it possible to sell large quantities of goods without freezing the market?

Price reliability: Are there consistent, globally referenced prices?

Custody risk: Can the assets be held without operational failure?

Operational integration: Is it possible to integrate with the margin system without human intervention?

For years, most tokenized assets have failed this test, even those actively traded on exchanges. This is because trading volume alone is insufficient. Clearinghouse margin accounts are controlled environments with stringent custody, reporting, and liquidation rules. Assets that do not meet these standards cannot be used there, regardless of demand.

The CFTC's decision is significant because it alters the legally permissible range of margin that clearing members can accept in regulated derivatives markets, where collateral is not a flexible option. Clearing members are heavily constrained in how they hold assets on behalf of clients, value them, and handle capital requirements. Even if an asset is highly liquid, it cannot be accepted as margin unless explicitly permitted by regulators. Prior to this decision, this restriction applied to crypto assets.

According to CFTC guidance, Bitcoin, Ethereum, and USDC can now be integrated into existing margin frameworks and subject to established risk controls. This removes a regulatory constraint that previously prevented institutions from integrating these assets into their derivatives businesses, regardless of market depth.

Margin systems rely on consistent pricing, predictable liquidation, and operational reliability under pressure. Assets that cannot be valued intraday, require discretionary handling, or have slow settlement create the risks that liquidation aims to mitigate.

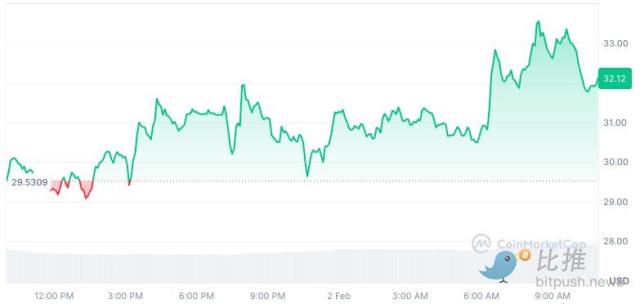

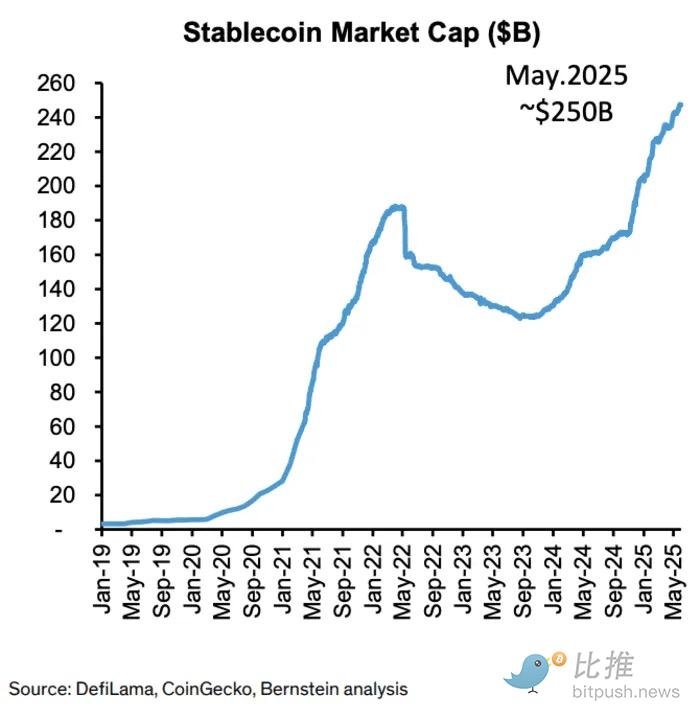

USDC meets these criteria because it already supports large-scale, high-frequency transaction flows. The stablecoin supply has increased from approximately $27 billion in 2021 to over $200 billion today, with on-chain transfers exceeding $2 trillion per month. These figures reflect the regular flow of funds between exchanges, trading desks, and treasury operations.

From the perspective of the margin system, this is very important because USDC can be transferred at any time, settlement is fast, and it is not dependent on bank business hours or correspondent banking networks. This allows it to be used for margin calls and collateral adjustments without modifying existing processes.

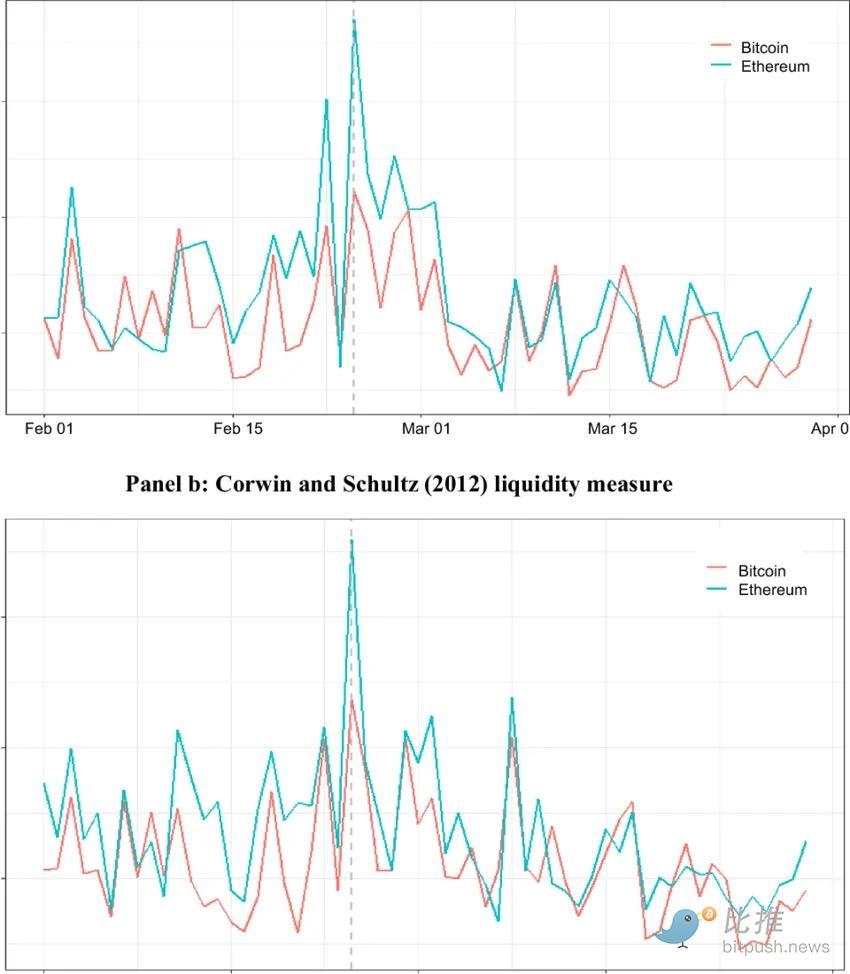

Bitcoin and Ethereum follow a different logic. Volatility itself does not disqualify an asset from entering the derivatives market. The key lies in whether price risk can be managed "mechanically."

Bitcoin and Ethereum are traded continuously on multiple platforms, have high liquidity, and have widely consistent reference prices.

This allows clearinghouses to apply haircuts, calculate margin requirements, and execute liquidations using established models. Most other tokens cannot meet these requirements.

This also explains why regulators haven't started with tokenized stocks, private credit, or real estate. These assets introduce legal complexities, fragmented pricing, and slow liquidation timelines. In margin systems, liquidation delays increase the likelihood of losses spreading beyond the original counterparty. Therefore, collateral frameworks always begin with assets that can be quickly priced and sold under stress.

While the CFTC's decision has a limited scope, its implications are significant. A small subset of tokenized assets can now be used directly to absorb losses in leveraged markets. Once assets are approved to play this role, they become part of the leverage expansion and contraction mechanism throughout the system. At that point, the primary constraint will no longer be whether the assets are compliant, but rather whether these assets can be moved and settled efficiently when margin adjustments are needed.

Settlement is where capital is actually "trapped".

Collateral determines whether leverage can exist, while settlement determines how long capital needs to be locked up after it exists.

In most financial markets today, transactions are not completed instantaneously. After a transaction is agreed upon, there is a delay before ownership changes and cash is delivered. During this period, both parties are exposed to each other's risks, and both must hold additional capital to cover those risks. This is why settlement speed is crucial: the longer the settlement time, the more idle capital remains (as protection rather than for reuse).

This is the problem that tokenization attempts to solve at the infrastructure level.

The Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation ( DTCC ) occupies a central position in the U.S. securities market. It is responsible for the clearing and settlement of stocks, bonds, and funds. If the DTCC cannot process transactions, the market cannot move forward. This is why changes at this level are more important than changes at the trading platform or application layer.

The SEC's "no-action letter" allows the DTCC to test tokenized settlement systems without triggering enforcement. This is not a green light for cryptocurrency transactions, but rather allows it to experiment with how to use "tokenized representations" instead of "traditional ledgers" for the settlement, recording, and reconciliation of transactions.

The key issue that DTCC addresses is balance sheet efficiency.

In current settlement models, capital is locked up during the settlement window to protect against counterparty default. This capital cannot be reused, pledged, or deployed elsewhere. Tokenized settlement shortens or eliminates this window by enabling near-instantaneous transfer of ownership and cash. As settlement speeds up, less capital needs to be idle as insurance.

This is why settlement is a larger constraint than most people realize. Faster settlement not only reduces operational overhead, but it also directly impacts how much leverage the system can support and the efficiency of capital circulation.

This is why regulators feel comfortable starting here. Tokenized settlement doesn't change the objects of the transaction, nor does it change who is allowed to trade. It changes how obligations are fulfilled after the transaction is completed. This makes it easier to test within the existing legal framework without redefining securities law.

Importantly, this approach retains control where regulators want it: settlement remains permissioned. Participants are known. Compliance checks still apply. Tokenization is used to compress time and reduce reconciliation, not to remove regulation.

When you connect this to collateral, the logic becomes clear: assets can now be submitted as margin, and regulators are testing systems that allow these assets to move and settle more quickly after position changes. These steps collectively reduce the amount of capital that needs to be idle in the system.

At this stage, tokenization is enabling existing markets to accomplish the same amount of work with less capital.

What kind of tokenization is actually permitted?

At this point, the matter is clear: regulators are not deciding whether tokenization should exist, but rather where it should be placed on the financial stack.

The current consensus is that it is accepted where operational friction can be reduced without altering legal ownership, counterparty structure, or control. As long as tokenization attempts to replace these core elements, its progress will slow or halt.

This can be clearly seen from the accumulation of actual transaction volume.

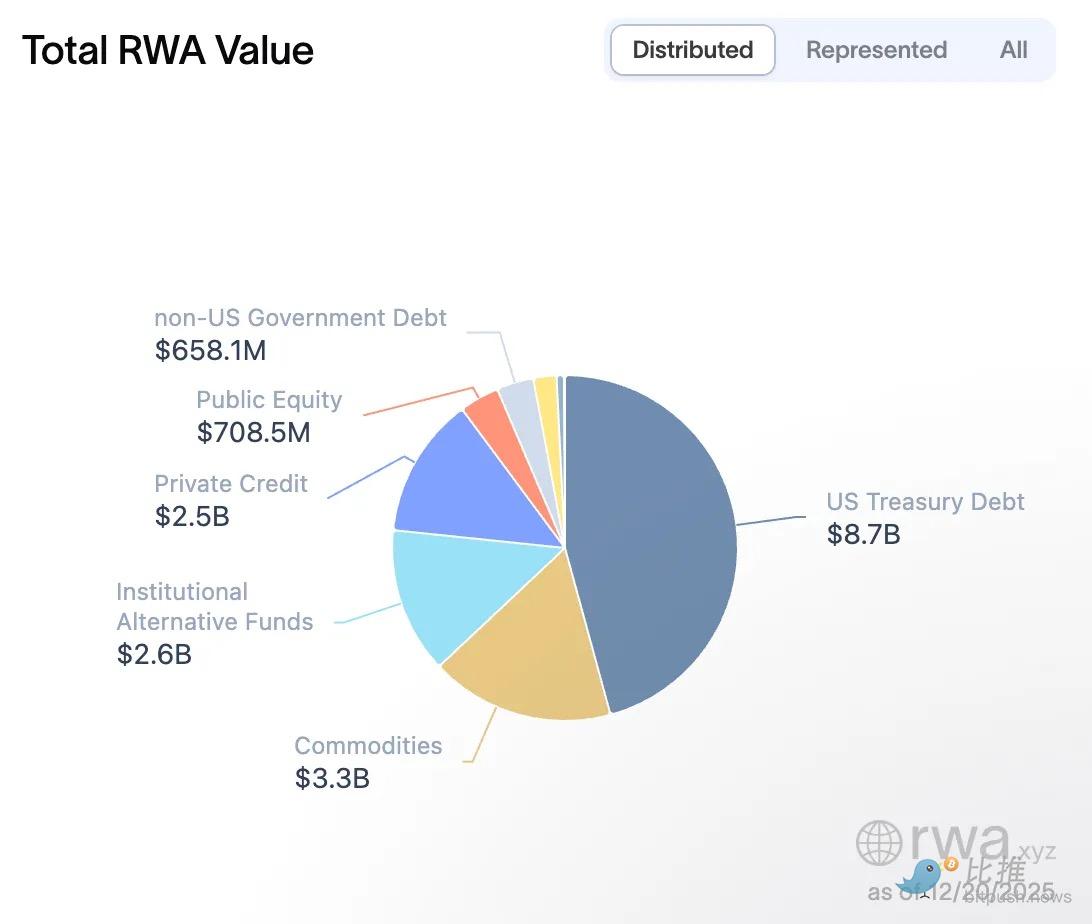

Aside from stablecoins, the largest class of tokenized assets today is tokenized US Treasuries. While their total value remains small relative to traditional markets, their growth model is significant. These products are issued by regulated entities, backed by familiar assets, and redeemed at net asset value. They do not introduce new market structures but rather compress existing ones.

The same pattern has also appeared in other tokenized products that survived after contacting regulators. They share several common characteristics:

Issuance is licensed.

The holder is known.

Custody is handled by a regulated intermediary.

Transfers are restricted.

The redemption definition is clear.

These constraints are what allow tokenization to exist in regulated markets without breaking existing rules.

This also explains why many early attempts at tokenizing "permissionless" real-world assets (RWAs ) stalled. When tokens represent claims on off-chain assets, regulators are less concerned with the tokens themselves and more with the legal enforceability of the claim. If ownership, priority, or liquidation rights are unclear, such tokens cannot be used in any large-scale risk management system.

In contrast, tokenized products currently scaling up appear to be "intentionally made to be uninteresting." They closely mimic traditional financial instruments, primarily leveraging blockchain at the infrastructure layer to achieve settlement efficiency, transparency, and programmability. A token is a "wrapper," not a reinvention of an asset.

This framework also explains why regulatory initiatives regarding collateralization and settlement predate the broader tokenization market. Allowing tokenization at the infrastructure layer enables regulators to test its benefits without revisiting complex issues such as securities laws, investor protection, or market structure. It's a controlled way to adopt new technologies without redesigning the system.

In summary, tokenized assets are being gradually integrated into the traditional financial system in a bottom-up manner. First, in the area of collateral, and then in the settlement process. Only after these two underlying foundations are proven and solidified will the expansion to more complex financial instruments have practical significance.

This also means that the tokenization model that may develop on a large scale in the future will not completely replace the existing market with open, permissionless decentralized finance, but is more likely to be the adoption of tokenization technology by the existing regulated financial system to improve operational efficiency, reduce capital occupation and reduce operational friction.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/BitpushNewsCN

BitPush Telegram Community Group: https://t.me/BitPushCommunity

Subscribe to Bitpush Telegram: https://t.me/bitpush