Author: Zhi Wubuyan

Edited by: Pat

Link: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/fhQAIIukaDMRWP-1rOlisw

Link: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/fhQAIIukaDMRWP-1rOlisw

Disclaimer: This article is a reprint. Readers can obtain more information through the original link. If the author has any objection to the reprint format, please contact us and we will modify it according to the author's request. This reprint is for information sharing only and does not constitute any investment advice, nor does it represent Wu Blockchain views or positions.

I. Introduction to this issue

When we talk about RWA (Real-World Asset On-Chain), we often refer to those "wild" wrapped tokens on the blockchain. But on Friday, December 12, the "backstage boss" of the financial world—the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC)—received a three-year pilot license from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Unlike previous tokens where shares were purchased by third parties and then repackaged, this time, DTC, a subsidiary of DTCC responsible for core custody, directly digitized the assets at the source. The core of this mechanism is "locked-up general ledger, distributed flow": DTC locks the shares in a centralized digital integrated account, allowing compliant institutions on the whitelist to achieve 24/7 atomic settlement on the blockchain through registered wallets. DTC also holds the root wallet, retaining the highest authority to force transaction rollback.

As of June 2025, the assets under custody by DTC have exceeded $100 trillion. To give you a more intuitive understanding of this figure, please refer to the following comparison: it is equivalent to about 90% of the global annual GDP and more than 30 times the total market capitalization of cryptocurrencies. These $100 trillion in assets are mainly composed of stocks ($74.1 trillion), ETFs ($11 trillion), and money market instruments ($4.1 trillion).

This is not a disruptive revolution, but a carefully designed "embedded improvement." In this episode, we break down the details and background of the DTC pilot program and attempt to answer a harsh question: When Nasdaq and Wall Street investment banks get involved, who will be the biggest winner and loser—Coinbase, Robinhood, centralized exchanges, and projects that create stock-encapsulated tokens?

Guest Zheng Di

A cutting-edge technology investor who manages the knowledge-sharing community "Dots Institutional Investors" (Community ID: 22136749).

Host Hazel Hu

Host of the podcast "Zhi Wu Bu Yan" (meaning "Speak Without Hesitation"), with 6+ years of experience as a financial media journalist, a core contributor to the Chinese Public Goods Foundation (GCC), and a focus on the practical applications of encryption. X: 0xHY2049; Jike: A careless Yueyue.

II. The Reformists' Entrance Ceremony and Red Line

Hazel:

Hello everyone, listeners of "Zhi Wu Bu Yan" (Speak Out Without Hesitation), welcome to a new episode.

Today we've invited our old friend Zheng Di again to discuss a very important piece of news from last Friday: the U.S. Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) announced that its subsidiary, DTC, received a "No-Action Letter" from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), allowing it to provide on-chain tokenization services for real-world assets in a controlled production environment for a three-year pilot period.

The assets covered in this pilot program are primarily highly liquid assets, including Russell 1000 index constituents, ETFs tracking major indices, and U.S. Treasury bonds. This is clearly related to the topics we've discussed repeatedly before, such as "US stocks on the blockchain" and "everything on the blockchain."

Zheng Di is one of my friends who has done the most in-depth research on this issue, so I've invited him to talk about it today: What exactly did the SEC say in its letter to the DTC? Why is it so important? And what profound impact might it have?

Zheng Di:

This document can actually be viewed in two parts:

Part of it is the DTC's request for no action submitted to the SEC;

The other part is the formal response from the SEC that day.

Both documents were released on the 11th. In its reply, the SEC agreed to the DTC's request and pledged not to take enforcement action for three years under certain conditions.

It's important to note that the three-year exemption period does not begin immediately, but rather is calculated from the date the DTC officially launches the pilot program. According to the DTCC's own press release and Nasdaq's statements in September, the pilot program will likely launch in the second half of next year, most likely in the third quarter.

The key to understanding this issue lies in the fact that it is actually a compromise, a path of "embedded transformation," rather than a direct impact on the existing financial system. The reason it has reached this point can be traced back to an open letter Nasdaq wrote to the SEC in June of this year.

At the time, Nasdaq explicitly opposed trading US stocks on the blockchain. Their main reasons were several: first, on-chain trading would create parallel markets, diverting liquidity from existing exchange-traded markets; second, it would weaken price discovery mechanisms, making liquidity management and market making more difficult; and third, it would impact existing risk control and market structure. These views were actually highly consistent with the core reasons why major market makers (such as Citadel Securities) opposed trading US stocks on the blockchain.

In its letter, Nasdaq also cited the reality of the crypto market: even for native crypto assets like Bitcoin and Ethereum, the vast majority of trading volume does not occur on-chain, but rather in the off-chain systems of centralized exchanges. Therefore, they argued that forcibly moving securities trading on-chain is not practically necessary.

However, Nasdaq also explicitly acknowledges that blockchain can significantly improve efficiency in issuance, transfer, settlement, and clearing. Therefore, their proposed approach is that transactions can remain on the exchange, but issuance, transfer, settlement, and clearing can be gradually moved to the blockchain. They specifically mentioned that Investment Contracts, as defined in the Securities Act of 1933, are more suitable for direct on-chain trading because traditional exchange-traded transactions do not exist in the real world.

By September, the regulatory environment had changed significantly. At the end of July, the SEC Chairman, when introducing and explaining Project Crypto, publicly stated that one of the SEC's missions was to facilitate the gradual migration of the US financial system from off-chain to on-chain. Against this backdrop, Nasdaq issued a new public statement in September, softening its stance considerably. It argued that by embedding modifications to the DTCC/DTC back-end systems, security tokenization could be gradually achieved without disrupting the existing system.

This is a typical reformist approach, not a revolution, but a gradual integration. I also used an analogy at the time, saying that Nasdaq is more like a "reformist" on this issue, not rejecting blockchain, but hoping that it will enter the financial system in a way that does not disrupt the existing order.

The proposal submitted by DTC to the SEC is a concrete implementation of this approach. Structurally, DTC does not change the existing securities registration and clearing system, but rather adds an Omnibus Account. Only formal participants in the DTC program, namely investment banks, securities firms, clearing houses, and custodian banks, can participate in the pilot program. These institutions can apply to mint some securities into on-chain tokens and transfer them to this Omnibus Account.

However, a crucial point is that on-chain transfers do not equate to a transfer of ownership in the sense of securities law. Legally, changes in ownership of stocks and bonds are still based on the off-chain electronic registration records of DTC. On-chain transfers only occur within the Omnibus Account and do not trigger a legal transfer of ownership.

The actual change of legal ownership occurs when the token is redeemed and a compliance agency issues a formal instruction to the DTC, returning the security to the off-chain system and registering it under the name of the ultimate holder. This is entirely consistent with the current financial system's core logic of electronic records, except that electronic records may gradually evolve into on-chain records in the future.

At the risk control level, DTC is also very clear about its boundaries. Once securities are tokenized and transferred to the Omnibus Account, these assets will no longer be considered eligible collateral within the DTC system. These assets will be completely excluded when calculating margin and risk exposure. DTC does not prevent market participants from making bilateral collateralization or financing arrangements on or off-chain, but these actions will no longer be included in its official clearing and risk control system.

Regarding eligibility, only core participants of DTC are eligible to directly apply for wallet addresses from DTC; end clients cannot directly establish a relationship with DTC. However, investment banks and securities firms can apply for one or more authorized wallet addresses for their clients. In this case, on-chain transfers can be conducted between clients with the consent of the intermediary.

One direct benefit of this is that during DTC closures, night trading, pre-market and after-market hours, and even weekends, some clearing and collateral needs can be completed directly on-chain, significantly improving the efficiency of fund and securities transfers. However, correspondingly, all on-chain activities of clients are ultimately still subject to KYC, AML, and other compliance responsibilities borne by their intermediary institutions, which is not fundamentally different from traditional finance.

Regarding the technical roadmap, DTC did not specify which specific blockchain to use, but clearly outlined the bottom-line requirements: it must support KYC and whitelisted transfers, must have the ability to reverse or force rollback transactions, and must support hierarchical permission management. The document also explicitly mentions security token standards such as ERC-3643. This means that the final implementation may be a hybrid of public, consortium, or private blockchains, but it will certainly be highly compliance-oriented.

From a market perspective, this development has a substantial impact on the large number of unofficial US stock tokens (wrapped/synthetic versions) currently in existence. Once official, compliant security tokens backed by the DTCC emerge, funds that can enter the official system will have little need to continue using these "wild versions." The more likely future scenario is that compliant funds will enter the official system, while non-compliant demand will remain in the gray or underground markets.

Finally, it's important to emphasize that the DTC repeatedly states in its documents that stock tokens are not stocks themselves, but rather a mapping (entitlement) of the underlying securities rights. The overall design goal is not to disrupt the existing financial system, but to embed blockchain as a second settlement layer, improving the operational efficiency of the entire financial market in a transitional and improved manner. This is also my overall understanding of this pilot program.

Hazel:

Let me start with a basic explanation. At the beginning, I forgot to explain DTCC itself to the audience. DTCC stands for Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation of America. My understanding is that it's somewhat similar to China's China Securities Depository and Clearing Corporation (CSDC). Is that a fair comparison? Essentially, it's a centralized depository and clearing institution for stocks, right?

Zheng Di:

Yes, you can understand it that way.

Hazel:

Is it the only one in the US? Because there are other exchanges like the NYSE and NASDAQ, is it the only one? Or are there other similar institutions?

Zheng Di:

Basically, this is the only one. Here, I'd also like to clarify something that many people easily misunderstand: in the traditional US stock market, it's not actually investors or investment institutions that "directly" hold stocks; it's a two-tiered structure.

In other words, those who actually appear on the shareholder register are the DTC member institutions, mainly investment banks, securities firms, clearing banks, and custodian banks, who hold shares on behalf of their clients. Clients' rights are realized through these intermediaries, not directly registered on the company's register.

Therefore, you often see news headlines such as "JPMorgan Chase acquires more than 5% stake in [stock name]" or "JPMorgan Chase reduces its stake in [stock name] from 10.5% to 9.7%." This doesn't necessarily mean JPMorgan Chase is making proprietary investments. More often, it's acting as a clearing or custodian, holding these shares on behalf of its clients. The clients' names don't appear in the listed company's shareholder register; only the DTC (Deliverable-to-Trade) members are listed.

This is a typical two-tier structure. The tokenization pilot program for US stocks proposed by DTC this time essentially continues this structure: during the pilot phase, DTC only recognizes its member institutions, namely investment banks, brokerages, and custodians, as wallet creators and managers. They have the right to mint, redeem, and burn wallets, while customers themselves do not have this right.

Of course, if these intermediaries are willing to apply for wallet addresses for their clients, that is their own choice, but the DTC only recognizes these intermediaries at the institutional level.

III. The US Government's Overt Strategy of Global Liquidity

Hazel:

Yes, that's an interesting point too.

I had a brief chat with AI before the presentation, and it mentioned a difference: China Securities Depository and Clearing Corporation (CSDC) has access to the holdings information of every individual investor, meaning it knows what stocks you, as an individual, hold; while the US market has a two-tier structure with an institutional layer in between, which may be an important difference between the Chinese and American market structures.

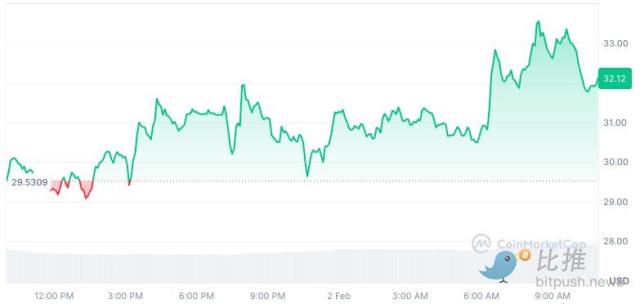

You just mentioned the impact of "unregulated" blockchain platforms for US stocks, which is exactly the question I wanted to follow up on. I don't know if you've been paying attention to the trading volume of these US stock tokens recently. Even before DTC launched this "sunshine" solution, did you think that the trading volume of these platforms had already encountered a bottleneck and might not be as large as people imagined?

Zheng Di:

Yes, this problem has indeed emerged. If you look at Nasdaq's current goals, they are very clear: it hopes to achieve 24/7 trading within one or two years. In fact, it is already very close to this state, because pre-market and after-hours trading are now widely available with very short intervals, essentially approaching continuous trading, except for the two-day weekend closure.

Against this backdrop, if you look at existing wrapped or synthesized US stock token trading, you'll notice a very obvious phenomenon: weekend trading volume is typically very low. The reason is simple—people are very concerned about pricing risks during non-trading hours.

For example, some typical platforms now adjust prices every 24 hours, but if the token price deviates from the underlying stock price by more than 10%, a forced correction will be triggered. For traders, this means that if you rashly place an order when liquidity is extremely poor and almost no one is trading, you could instantly lose more than 10% if a gap occurs at the opening.

Therefore, when trading is slow, people are less willing to trade. This is a very real problem.

I think the core point is that these stock tokens are essentially creating a parallel market. You're not directly connected to the main trading systems of the NYSE or Nasdaq; instead, you're providing a wrapped version of the trading market off-exchange. The biggest problem with parallel markets is insufficient liquidity.

We don't even necessarily need to use US stocks as an example. For instance, Paxos' gold token PAXG has an issuance size of over a billion dollars, but in some extreme market conditions, its price fluctuates wildly. If you directly hold physical gold, there's not much of a problem; however, if you're trading these token derivatives on the secondary market, it's easy to trigger margin calls due to insufficient liquidity, or even face liquidation.

So ultimately, the first and biggest problem is liquidity. The second problem is counterparty risk.

Many people worry: These tokens are issued by a certain platform, so what is the platform's balance sheet? Will it go bankrupt? If the platform has problems, am I doomed? For example, when BAKKT was still an independent company, the market's trust in it was limited; after it was acquired by Kraken, the situation may be better, but you still have to face a clear counterparty risk.

In contrast, if an official system like a DTC were to operate, the market would at least be less concerned about counterparty risk. In this case, many people would naturally ask: why not trade on the main market?

For example, we've seen news today that Interactive Brokers is willing to accept stablecoin deposits from some US users. If you disregard complex factors like CRS and taxes, for many people, trading directly through a mature brokerage system already offers a very good experience. In this context, the attractiveness of on-chain US stock tokens will naturally be challenged.

Therefore, I believe that the biggest bottleneck at this stage is still liquidity.

Hazel:

Yes, I actually have two levels of questions here:

On the one hand, the "wild" US stock token platforms are, to some extent, validating a demand: how many people really need to buy US stocks on-chain?

On the other hand, traditional brokerage services are indeed evolving rapidly. Brokerages like Interactive Brokers and Futu are constantly improving their deposit and trading experiences, and even if they don't offer 24-hour trading, they can generally cover night trading sessions.

In this context, what is the real need behind DTCC's push for a formal and transparent solution for putting US stocks on the blockchain? Why is it necessary to push this onto the blockchain?

Zheng Di:

I believe the core reason is that the current SEC chairman himself has a very strong belief in the speed of on-chain finance and its potential for integration with the DeFi system.

However, there are some underlying motivations that the authorities haven't explicitly stated: that not all brokerages and banks will completely obey the US government in the future. US assets want to continue attracting global liquidity, hoping that funds from around the world will be allocated to US stocks and used to finance US assets. But the reality is that some countries may restrict their institutions or residents from trading US stocks.

In this context, if the United States wants its assets to continue "siphoning" global funds, it must consider migrating some of its infrastructure to the blockchain. This is because the blockchain is a very special space that no single government can fully control.

To put it bluntly, in the past, governments around the world viewed blockchain as a "gray area that could be exploited internationally." Now, the United States is gradually realizing that even if it cannot completely control the blockchain system, if it can exert enough influence, it can bypass many real-world regulatory and geopolitical obstacles.

For example, with the EU, it's difficult to directly say, "I'm banning US assets"—it can't do that kind of overturning of the rules. It can only do it by issuing licenses and setting rules. But once the other party obtains compliance qualifications like MiCA or MiFID II and provides services within your framework, even if you're unhappy, it's difficult to truly stop them.

Therefore, I believe that, from a longer-term perspective, the United States is consciously using on-chain finance as a tool for global financial competition. This is the most fundamental reason.

Secondly, there are some relatively minor but also very real reasons. For example, suppose you have an account at Goldman Sachs and I have an account at another investment bank, and we want to conduct a large off-exchange transaction, such as trading Nvidia stock. Under the current system, we cannot transfer the shares directly; we must go through the DTC (Demand-Traded Company) and complete the transaction during their business hours.

However, if stock tokens are introduced, under the new pilot rules, I can complete the transfer simply by transferring the tokens to you. Transfers can be made on weekends and at night. If you urgently need collateral, financing, or margin calls, and banks are closed, this efficiency improvement is very real.

Ultimately, however, these are all secondary reasons. The core reason remains the United States' desire to maintain its attractiveness to global capital within a future global financial system characterized by "high walls and a small courtyard." "On-chain" technology may be one way for it to overcome these walls.

Hazel:

What's your take on the recent shift in China's attitude towards the narrative surrounding "stablecoins"? It was quite enthusiastic for a while, but recently it's cooled down significantly, with many platforms even ceasing their pronouncements. Do you think this reflects a clearer understanding of the US's true intentions, leading to a decision to "stop playing along"?

Zheng Di:

From what I understand, there is at least one very real reason for this: some large-scale pyramid schemes operating under the guise of "stablecoins" have indeed emerged in China, and they are packaged very convincingly.

I've seen some cases, such as the so-called "Huawei stablecoin." Not only was the scheme very well-developed, but they also mailed so-called "Huawei-ICBC joint settlement cards" directly to the homes of some elderly people, and even the account opening notices were very elaborately made. At the same time, they created WeChat groups, and there were even fake "Meng Wanzhou's voices" in the groups, teaching everyone how to use the "Huawei stablecoin." The scale of such projects is already quite large.

Therefore, I think that from a regulatory perspective, this is a very direct triggering factor.

IV. Public blockchains, brokerage firms, exchanges… who benefits and who loses?

But if you ask if there are deeper, more structural reasons, then there certainly are. For example, they may have already determined that in the stablecoin arena, the market share of US dollar stablecoins has reached 98% or 99%, and no matter what you do, it's difficult to truly compete with the US in this area. In that case, they might as well completely abandon the stablecoin route and shift resources and narratives to the digital yuan.

Moreover, to put it bluntly, your rejection of "stablecoins" is essentially a rejection of "dollar stablecoins," and what you really want to counter is the dollar's buffer and its systemic spillover capabilities. Europe is also trying to prevent dollar stablecoins, but it can't directly "flip the table" like China does. It can only restrict you by issuing licenses and setting rules—you follow my rules first, and I'll deal with you when you break them.

But regardless of the method, one thing is clear: once US assets and dollar assets begin to be put on the blockchain on a large scale and systematically, this asset hegemony will become more "invisible" and more difficult to resist. This is a very clever strategy, and that is my basic judgment.

Returning to the issue of "US stock tokens" you mentioned earlier, I've always felt that these packaged US stock tokens are in a rather awkward position.

Since May of this year, I have had a fairly clear judgment: if the Web3 industry does not experience a new round of explosive growth in native assets, and there is no innovation in new asset forms, but instead moves towards a process of "traditional assets being put on the blockchain"—I use a neutral term, "the vulgarization of traditional assets," without any derogatory connotation—then in this process, CEXs are likely to be the losers, while internet brokerages will be the winners.

The reason is actually quite simple. Online brokerages are generally significantly stronger than CEXs in terms of traffic management, product experience, and information services. Take Futu, for example; in terms of functionality and user experience, almost no CEX can match it.

Furthermore, if in the future people mainly trade US stocks, US bonds, or US stock tokens, then platforms like Futu and Robinhood will easily "steal" users that originally belonged to CEXs; but conversely, it is very difficult for CEXs to steal users from online brokerages, because their traffic capabilities, community capabilities, and information capabilities are not on the same level.

Some might argue that centralized exchanges (CEXs) aren't entirely devoid of community. True, some do exist, but the problem lies in the fact that their community narratives and justifications have long revolved around "native crypto assets." Now, there's not much to say about native crypto assets themselves; they're even relying on Memecoin to stay afloat. In this context, how do you guide users to trade US stock tokens?

You can't simply say, "I've launched this asset," without any investment research, information push, or discussion forums, and then expect users to spontaneously speculate on it; that's practically impossible in reality. Moreover, even just considering the product itself, the liquidity and user experience of US stock tokens on many centralized exchanges are far from ideal.

So if you're a big player in Web3, or a relatively sophisticated investor, you're likely to "go out of the circle"—for example, if IB allows non-US users to access it stably in the future, then they'll go directly to IB or Futu. Why would they trade a US stock token on a CEX with worse liquidity and a weirder experience?

Unless a CEX can provide a complete suite of information services, community discussions, and content offerings similar to "Futu Niu Niu Circle," it might retain at least some users. However, I have doubts about whether it can attract new users. Overall, the "core characteristics" of this business don't particularly align with the existing CEX system.

I'd also like to add that Chinese people are generally better at app development than foreigners. I use IB myself; its advantage lies in its comprehensive tools, especially for creating derivative products. However, it has a significant weakness: it almost entirely lacks push notifications.

Futu, on the other hand, has purchased a large amount of information services, and will immediately push notifications to you when there are any slight changes in the market, telling you what happened; in addition, its own community, although it does not have investment research in the traditional sense, has a large number of users in NiuNiu Circle who continuously discuss stocks, forming a spontaneous information field.

Robinhood has recognized this, and it's trying to build a similar community itself. This illustrates one point: if you lack investment research capabilities, you must at least have a community; and if you don't even have a community, users have no reason to stay with you.

The problem is that if the future truly involves "US stocks and bonds being fully on-chain," rather than the emergence of new native assets, then the existing community and KOL structure of CEXs are actually incapable of discussing these assets. They don't understand them, nor can they guide the discussion, so why would users trade US stocks on your platform? Even if it's to avoid CRS, they may not trust you because the community atmosphere, user structure, and discussion methods are completely mismatched.

Hazel:

But at this juncture, such as Kraken's acquisition of Backed Finance, which you mentioned yesterday, doesn't it seem a bit awkward? Or are they actually preparing for another narrative? Binance, for example, recently launched US stock-related products in its wallet.

Zheng Di:

I think Binance launching US stock-related services was the right thing to do, and a very right thing to do. You can clearly see that the liquidity of these US stock tokens has indeed improved after they were listed on Binance.

But the problem remains the same as I mentioned earlier: you can't just release a "feature" and call it a day. Many people won't even know you've launched it; even if they do, they might not necessarily transact with you. It depends on whether you treat this business as a "peripheral feature" or a core direction that truly requires investment of resources and a clear narrative.

If you're just relying on organic traffic and saying, "I've given you the tools, use them or not," without discussion, content, or a voice, then this business will find it very difficult to truly grow.

As for Kraken, I'm more inclined to believe that it's anxious about its existing growth narrative. Kraken's valuation has risen very quickly. I remember when I was giving a lecture to Futu VIP users this June, its previous valuation was only over $5 billion, but now the market has pushed it to around $20 billion, and it's even planning an IPO.

So here's the question: how do you explain a "spot exchange" with a valuation of over $20 billion to the market? There are many exchanges in the US, but the first thing that comes to mind is always Coinbase as the leader. Even Arbitrum, after its IPO, was only valued at about one-seventh of Coinbase's.

More importantly, Coinbase itself has stopped telling the story of a "spot exchange" and is now talking about "on-chain financial infrastructure." This is because for compliant exchanges, the real enemy over the past two years hasn't been online brokerages, but rather ETFs.

ETFs have very low fees, and each additional spot ETF will further squeeze Coinbase's retail trading fee revenue. This means that retail spot trading is inherently a business destined to continue to decline.

This is why Coinbase was willing to pay any price to acquire Deribit—because Deribit's derivatives business is highly complementary to Coinbase's, and although it's not large in scale, it's on the right track. This shows that Coinbase is very clear: it must transform.

From a "chain-based" perspective, my personal feeling is that layer-two chains might be more suitable than layer-one chains. This is because you need compliance modules and reversible capabilities, which are easier to customize on layer-two chains. Coinbase is clearly trying to make Base its core narrative; its 80% profit margin essentially comes from its control over the Sequencer.

Therefore, I feel that Kraken also needs to tell a new story; it can no longer rely on being a "pure spot exchange" to support a $20 billion valuation. Its acquisitions of banking assets and Ninja are essentially attempts to find new narrative footholds.

As for the business of "US stock token packaging," its potential has definitely been significantly reduced after DTCC's actions. Just like when starting an internet business in China, the eternal question was: what if BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) copies you? This question has never had an answer.

The same question now arises: what can you do when the official DTC itself gets involved in putting US stocks on the blockchain?

You could argue that DTC's version has high permissions and many restrictions, which may not be suitable for everyone, and the market may use a "faster" version. But at least at this point in time, we can make a judgment: the growth potential of all projects that do US stock token packaging and token encapsulation business has been significantly compressed.

Historically, the only truly large-scale wrapped token business is WBTC. A major reason for this is the poor interoperability of BTC with other ecosystems. Before Layer 2 architectures emerged, WBTC was the only way to bring BTC into Ethereum. Apart from that, there are very few truly large-scale wrapped token businesses.

Therefore, I believe that this round of changes has a real impact on CEX and related packaging businesses.

Hazel:

You just mentioned the possibility of layer 2 chains, which is actually where many people in the crypto are trying to find a "profit angle".

What does this mean for Ethereum and Solana? Solana has been talking about on-chain capital markets, and Ethereum has recently been moving towards "everything on-chain".

But based on the current design, I have a few questions:

First, Layer 1 does not seem to directly benefit;

Second, the document mentions transfers between wallets registered by DTC participants. Does that mean these tokens can never enter the DeFi protocol? Or is it theoretically still possible?

Zheng Di:

Here's the thing: Regardless of whether it's currently in the testing phase or even in the official phase in the future, removing the word "testing," these stock tokens, the on-chain money market funds (TMMF) we've seen before, and tokenized deposits like the on-chain deposit token JPMD are all essentially securities. This is because what you're providing is yield, or expected yield.

All securities, within the compliance framework, must be transferred using a whitelist, and must be subject to controlled transfer; permissionless transfer is impossible. This is a definitive conclusion. Therefore, regardless of whether you use a public blockchain, a layer-two blockchain, or another architecture that they accept, you must embed a whitelist system at the code level—addresses not on the whitelist simply cannot transfer funds.

This is why Atkins mentions ERC-3643, and why DTCC explicitly mentions 3643. The reason lies in their compliance module, which allows you to directly write the whitelist into the contract logic. If a new person wants to be added to the whitelist in the future, you only need to enter their address and KYC information.

I even think that in the future, a scenario might emerge where the vast majority of on-chain protocols operating under "sunshine regulation"—including payment, clearing, and controlled DeFi—will likely share one or more whitelist systems. Why? Because payments also require KYC and anti-money laundering measures. Institutions like Visa and Mastercard already have mature whitelist systems; they just need to incorporate these rules into their contracts.

In this scenario, participation in DeFi is not entirely prohibited, but it can only be limited to whitelisted DeFi transactions. If you can't even transfer tokens, then you can only perform protocol interactions between controlled addresses.

This is why I've always said that there will still be a market for tokenized versions of assets. Who will use them? Either those not on the whitelist, or those unwilling to use whitelisted addresses for transactions. This essentially creates a gray market or black market.

Therefore, my long-term judgment has always been that Web3, in its final stages, will be highly isomorphic with the traditional internet—both will compete for users and traffic. "Purely technical services" like token wrapping have very shallow moats. Once the official platform releases a transparent version, why would they still need token wrapping? Aside from gray-area demands, this question is very difficult to answer in the compliant market.

Hazel:

Let's get back to Coinbase. You've already analyzed some of the impacts. A fairly intuitive guess is whether the Base chain will become the infrastructure for these on-chain transfers and transactions? Besides Base, are there any other beneficiaries for Coinbase? For example, Coinbase Prime, custodial wallets, etc.?

Zheng Di:

I think Coinbase has its ups and downs. Let's start with the good.

First, the trend of "everything on the blockchain" is becoming increasingly clear. I would be quite surprised if Base Chain ultimately doesn't make it onto the DTCC's list of approved or usable blockchains. Because if even Base Chain isn't viable, which public blockchain can we use? Otherwise, we're left with consortium blockchains and private blockchains.

In reality, BlackRock's BUIDL (TMMF) is built on the Base blockchain, and JP Morgan's JPM deposit token is also deployed on the Base blockchain. Although these security tokens cannot be freely transferred on Base yet, at least during the technical deployment phase, Base is the first choice for financial institutions.

Therefore, I think it's natural that Base will be given priority consideration for these "controlled versions" of US stock tokens in the future; at the very least, it will definitely be one of the candidates.

Secondly, Coinbase's profit margin is extremely high. Some say it accounts for up to 70% of revenue within the OP ecosystem. Although there are plans for Superchain and rotating sorters after OP, Coinbase is clearly unwilling to relinquish control of the Sequencer. Unless the SEC mandates it, I think this struggle will continue for at least another year or two, and a resolution is highly unlikely next year.

Therefore, as long as these assets and trading activities are transferred to Coinbase, under the current high-profit margin structure, it will be a direct benefit to Coinbase's profitability.

Looking further ahead, agent payments will definitely be on-chain, and will most likely be stablecoin payments. Coinbase's x402 protocol and USDC are both clear beneficiaries of this trend.

Previously, when you were on an off-chain exchange, you didn't necessarily need stablecoins; you could deposit and withdraw funds using fiat currency. But on-chain, you must use stablecoins.

Moreover, a more realistic situation is that while USDT has a strong advantage in centralized exchanges and some payment scenarios, USDC actually has an advantage in on-chain transaction depth and usage. If USDT wants to fill this gap, it's not difficult by expanding its number of redeemers, but USDC currently holds a first-mover advantage.

Therefore, from a "future-oriented" perspective, Coinbase's transformation direction is correct: Base, USDC, and Agent payments are all in line with the trend. However, it also has its hidden concerns.

This concern hasn't been discussed much recently, but it's actually been brewing—the American banking union's lobby is now directly confronting Coinbase.

The problem lies with the Genius Act. This act only prohibits stablecoin issuers from paying interest, but not promoters. We all know that Circle is effectively an affiliate of Coinbase, and Circle shares 56%–58% of its revenue with Coinbase as "promotion fees." Coinbase then rebates USDC holders. Isn't this a form of disguised interest payment?

A key reason the Democrats were willing to accept the Genius Bill was that "stablecoins should not pay interest," to prevent a large-scale exodus of bank deposits. However, the current structure clearly circumvents the bill.

Therefore, the banking industry's stance is: demand legislative amendments to close this loophole. My personal judgment is that a compromise may ultimately emerge—prohibiting related parties from indirectly paying interest through rebates. For example, Circle and Coinbase are not allowed, but a partnership between Circle and Binance, with Binance subsidizing users, would be acceptable because they are not related parties.

If banks wield sufficient power, it's possible they will restrict Coinbase's participation as an affiliate in USDC revenue sharing in the future. This poses a potential risk to the long-term promotion of USDC.

By the way, I don't know if you've noticed, but Coinbase Singapore recently changed its policy: previously, you could earn rewards simply by holding USDC, but now you need to be a paid member of Coinbase One to receive them. I'm not sure if this is a global or regional strategy, but I intuitively feel it's related to this issue.

Hazel:

Your mention of the Democratic Party is quite interesting. Overall, US regulation is relatively friendly to blockchain, but the DTC only granted a three-year trial period. Given Trump's term and the midterm elections, is there a possibility of regulatory "regression"?

Zheng Di:

I am optimistic about the first half of next year, but will be significantly more cautious about the second half. A key risk factor is the midterm elections.

The prevailing expectation is that the Democrats and Republicans will each win one house of Congress, but we cannot ignore some signals: following the change in the New York governorship and several key states, Polymarket briefly suggested that a Democratic sweep was more likely than "each winning one house." Although there is still a long time before the November election, I would be very wary if the Democrats still hold a majority by the end of the second quarter of next year.

Once the Democrats regain control of Congress, I think the market will see a correction in both AI and Web3. It's not that the Democrats oppose these two industries, but their support is significantly less aggressive than that of the Republicans. AI faces ethical constraints, and Web3 won't be allowed to develop too rapidly.

Therefore, I predict that the general direction will remain unchanged, but the pace will likely be "one step forward, one step back". Moreover, the president has already greatly strengthened executive power through executive orders. If this trend continues, the real long-term variable will be the 2028 presidential election.

Currently, Vance is the most likely Republican candidate, with a significant lead on Polymarket. On the Democratic side, Newsom and AOC are both represented, but the gap is still quite large. If it's AOC, it won't be very favorable for either of these industries; if it's Newsom, he might be more pragmatic, but it's difficult to predict his stance three years from now.

In conclusion, I have substantial concerns about the midterm elections; it is indeed a market issue that cannot be ignored.

Hazel:

Yes, I won't speculate on the presidential election; it's just too difficult, especially since 2028 is still a long way off. We just finished talking about Coinbase, and I feel we haven't really discussed Robinhood in detail yet, because I know Mr. Di has done very in-depth research on Robinhood. Looking at this matter itself, do you think it's a long-term positive for Robinhood? Or are there some potential concerns?

Zheng Di:

Robinhood recently released its November data, and frankly, it's not good. You see a decline not only in its crypto business, but also in stocks and options – its first overall pullback since February. Previously, it had seen growth almost every month, with only November showing a significant drop, indicating that the overall market environment was indeed unfavorable in November. The only sector that performed relatively well was the prediction market.

However, Robinhood has a very important long-term theme: what if it ends its partnership with Kalshi and builds its own prediction market? It has already secured a DCM prediction market license with the SIG. While it hasn't disclosed the specific equity stake in the prediction market, I personally estimate it's likely over 50%, possibly even between 55% and 60%.

While the revenue sharing ratio between Robinhood and Kalshi hasn't been publicly disclosed, I'd guess it's somewhere between 33% and 50%. Once they build their own prediction market, the profit structure will definitely be much better than partnering with third parties. Plus, next year is a big year for prediction markets, and I think something will definitely happen on the political front before the midterm elections. From this perspective, I'm generally optimistic about Robinhood.

However, there is a very crucial variable here: regulation. In particular, if the Democrats gain greater control of the Congressional discourse, it could pose a challenge to Robinhood's business model.

As we all know, one of Robinhood's core models is PFOF (Payment for Order Flow). During the GME incident, it nearly faced a liquidity crisis due to issues with clearing and settlement cycles, with a shortfall of approximately three billion dollars. At that time, there were indeed voices within the Democratic Party attempting to investigate and even restrict this business model, but nothing came of it.

From today's perspective, if securities are truly recorded on the blockchain and near-real-time settlement is achieved in the future, then the systemic risks faced by Robinhood in the GME incident are likely to be avoided. This is actually a frequently overlooked but very important value of "securities on the blockchain."

Conversely, as long as the PFOF model exists, the market will be very sensitive to any changes in regulatory attitude. You see Robinhood with P/E ratios of 70 or 80, far higher than traditional brokerages. Besides its strong customer base and execution capabilities, another crucial reason is that the market is pricing in an expectation of "full blockchain integration in the future."

In other words, once businesses such as stocks and options are on-chain, Robinhood's profit margins are likely to be significantly higher than in the off-chain era. This expectation is already priced into the current stock price.

Hazel:

Do you think that the path that DTCC is currently pushing forward, and Robinhood's previous attempt at "putting US stocks on the blockchain," is a better situation for it?

Zheng Di:

I think it's definitely better. Because Robinhood's previous so-called "on-chain US stocks" can't strictly be implemented in the US market, and it's not really about putting securities on-chain, but rather CFD, which is a relatively independent and more restricted approach.

Furthermore, it had studied the Base chain and discovered that Base's profit margins were extremely high—in short, it was "enviable." Therefore, its desire to create its own "Base" is essentially to build a second-layer chain belonging to Robinhood. Its partnership with Arbitrum follows the same underlying logic as OP helping Coinbase build Base.

Since Base has clearly sided with the OP camp and is already the largest Layer 2 in the OP system, Robinhood cannot choose the same camp. Naturally, it will choose Arbitrum, the main competitor of OP. This is a very natural and commercially rational choice.

From this perspective, what DTCC is doing now is a real boon to the stability of Robinhood's future business model and the improvement of its profit margins. However, I must emphasize that Robinhood's business model is almost "invincible," and its only true enemy is regulation. If regulatory attitudes become significantly stricter, especially towards PFOFs, it will be a systemic blow to Robinhood.

V. The Era of 260 Trillion Yuan of Traditional Assets Being Put on the Blockchain

Hazel:

Finally, let's talk about the SEC innovation exemption that we've been discussing. You mentioned before that the DTCC is also waiting for this innovation exemption to be officially implemented. So, what's the current status of this process?

Zheng Di:

To be honest, this matter hasn't garnered much attention outside the crypto community, and overall market expectations are relatively low. Although Project Crypto's speech at the end of July was very inspiring, the detailed rules originally planned for release in April have been delayed until early next year due to factors such as the government shutdown.

My original baseline prediction was that a draft for comments would be released early next year, followed by a few months of public consultation. A pilot sandbox could be launched as early as the second quarter, and the full implementation of the formal rules could take two to three years, similar to the pace of ATS's development in the 1990s.

However, an interview with Atkins on December 2nd mentioned that "it will take effect early next year," a statement that leaves much to the imagination. If this is true, one possibility is that it will go through a fast track, bypassing the full consultation process. This is because innovation exemptions fall under the SEC's jurisdiction and do not require congressional approval.

Another possibility is that a sandbox-like pilot program will be launched directly in January next year, while formal rules are being developed simultaneously. Regardless of the scenario, the bottom line is that at least a substantial pilot program will be launched in January next year.

Why is this important? Because before the innovation exemption is truly implemented, traditional on-chain financial assets are almost "non-transferable." Many of the stocks and bonds you see deployed on Base, Solana, or other chains are essentially not tradable among US retail investors; they are only available to accredited investors or non-US citizens.

Galaxy's mapping of its shares onto the blockchain is a prime example. It can "put" them on the chain, but it cannot create any liquidity pools or provide trading services; otherwise, it would constitute an unregistered issuance and sale of securities. Therefore, without circulation, there is no market, and the whole thing becomes meaningless.

Therefore, innovation exemption is a prerequisite for the true launch of the entire traditional financial asset on-chain system.

If you look at the overall market size, traditional financial assets are approximately $260 trillion, while crypto assets are currently only slightly over $3 trillion, accounting for just over 1%. Of this $260 trillion, half is stocks, with over 60% of those stocks being US stocks; bonds account for 39%, with over 40% being US Treasury bonds; and gold accounts for approximately 6%.

This is why I've always believed that Web3 has three major future directions: first, stablecoin issuance and payments; second, blockchain-based ubiquitous connectivity (RWA); and third, the Agent Economy.

Within the broader concept of blockchain technology, there are three core sectors: prediction markets, blockchain-based US stocks and bonds, and blockchain-based gold. I believe blockchain-based gold represents a very large business opportunity. Tether's massive gold hoarding isn't just about waiting for gold prices to rise; it's about preparing for the future blockchain-based gold market.

Hazel:

If one day these 260 trillion yuan in assets are indeed put on the blockchain, from the perspective of the "water sellers," who will be the biggest beneficiary? Will it be the public blockchain, or securities firms and brokers?

Zheng Di:

I believe brokerages like Robinhood will be huge beneficiaries. Their markups, slippage, and rebates are inherently much higher than the fees charged by public blockchains.

However, from an infrastructure perspective, I'm actually more optimistic about Layer 2 chains. Previously, Layer 2 chains had to hand over 50%–70% of their revenue to the mainnet, but with the introduction of Blob, this cost has decreased by over 90%. Look at the Base chain; the fees it now hands over to the mainnet are probably less than 5% of its revenue, resulting in extremely high profit margins.

Ethereum is currently more like "accumulating water to raise fish," and fees are unlikely to increase significantly in the short term. Therefore, with the real launch of everything on the blockchain and mainnet fees remaining restrained, layer-two chains will be the clear beneficiaries.

This is why Robinhood is developing its own second layer; the logic is completely consistent with Coinbase's Base layer.

Hazel:

What about Solana? It doesn't have two layers.

Zheng Di:

Solana will eventually need some kind of "controllable layer," not necessarily a layer 2, but it must have a compliance module. From the perspective of putting compliant financial assets on-chain, I've always believed that currently only three are truly sitting at the table: Ethereum, Ethereum's layer 2, and Solana. I still hold this view.

The Solana Foundation is very proactive, and its roadmap is clearly outlined: "Internet high-speed capital markets" and "on-chain Nasdaq"—these narratives are attractive to traditional finance. Ethereum relies more on its reputation and institutional recognition accumulated over many years, but you have to admit that its action-taking ability is not as strong as Solana's.

Ideally, it would combine Ethereum's reputation with Solana's execution capabilities.

Hazel:

Is BNB not currently on the poker table?

Zheng Di:

I believe it's not currently there. It's not because it lacks these things, but because it hasn't clearly articulated "on-chain compliant financial assets" as a strategic priority. In the long run, if mainstream finance doesn't see you as a player at the table, there will be problems.

[Glossary]

DTCC (Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation) is the central securities custodian in the United States, responsible for handling the clearing and settlement services for the vast majority of U.S. stock and bond transactions.

A No-Action Letter is an official statement issued by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). It indicates that under specific facts and circumstances, if an entity engages in certain business practices, SEC officials will commit to not taking enforcement action against it.

An Omnibus Account is an account structure that allows the assets of multiple investors to be pooled under the name of a single custodian or broker, rather than being held in separate accounts in the individual names of each investor. This structure is often used to improve clearing efficiency and protect client privacy.

The ERC3643 standard is an Ethereum token standard designed specifically for compliant security tokens. Unlike ERC-20, it incorporates KYC/AML authentication logic at the smart contract layer, ensuring that only whitelisted wallet addresses that pass compliance checks can hold or receive tokens.

PFOF (Payment for Order Flow) is a business model where brokerages send clients' orders to market makers (instead of directly to exchanges) for execution, and in exchange, the market makers pay the brokerages a fee (rebate).

Project Crypto, a project concept proposed by SEC Chairman Atkins, aims to shift the infrastructure of the U.S. financial system from traditional off-chain ledgers to on-chain blockchains in order to leverage the characteristics of distributed ledger technology.