Author: BitMEX Research

Abstract : 64-byte Bitcoin transactions can be confused with the hash objects of a block's Merkle tree, as the latter are also 64 bytes long. We investigated how this vulnerability could be used to trick Simplified Payment Verification (SPV) clients into believing they have received a transaction when they haven't, and other problems this weakness can cause. While launching such an attack is very complex, and the vulnerability is not severe, there is a relatively simple fix: in a soft fork, disable all 64-byte transactions after stripping witness data.

Overview

This article is part of a series discussing the four security vulnerabilities that BIP 54 consensus cleanup soft forks will fix. We have already covered two of these vulnerabilities:

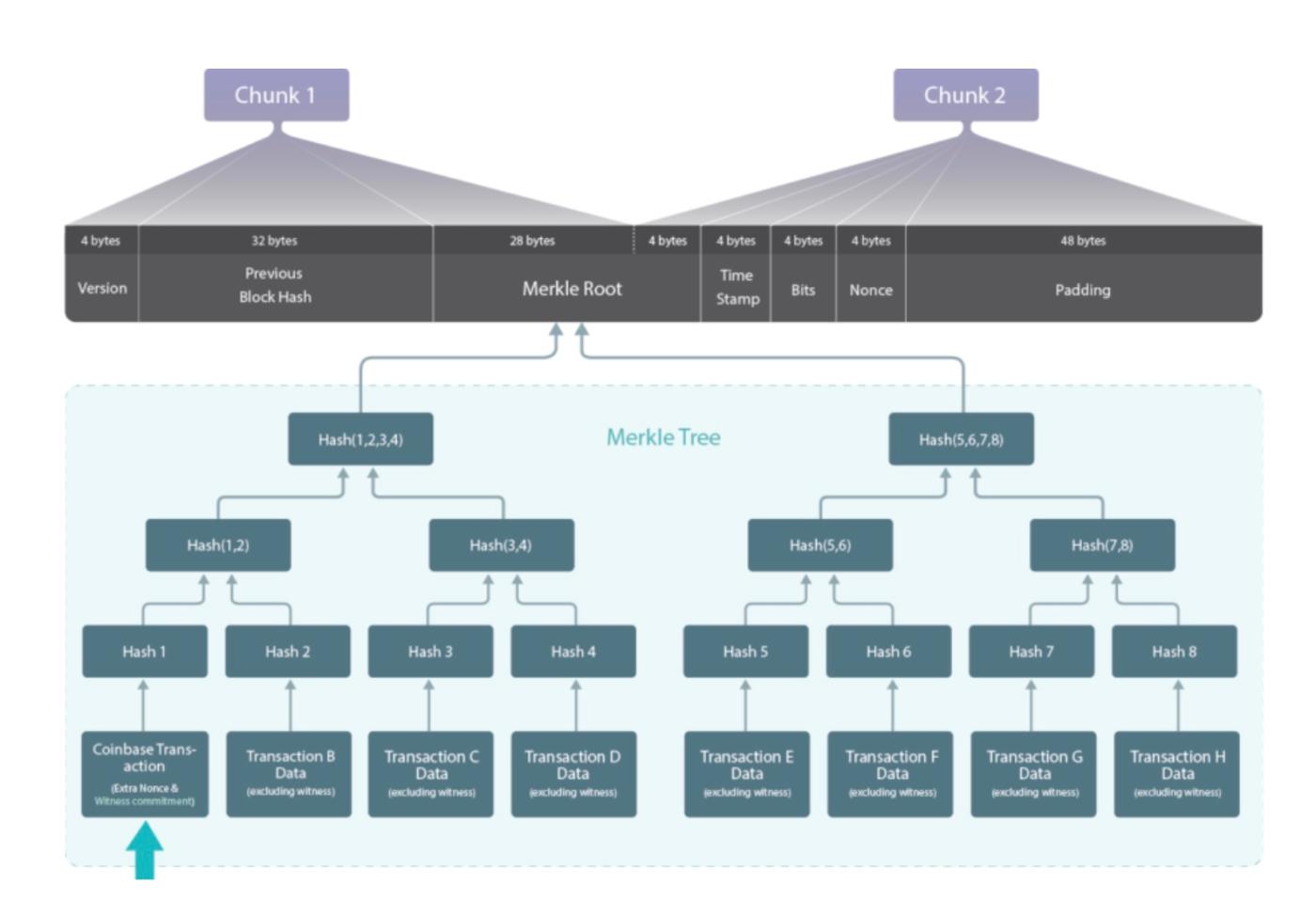

In this article, we will focus on the so-called "64-byte transaction" issue. The key point is that the hash object of the intermediate node in the Merkle tree used to generate the Bitcoin block is also 64 bytes long.

A Bitcoin transaction's hash, or "TXID," is 32 bytes long. The second-to-last line of the Bitcoin block's Merkle tree is the concatenation of two TXID hashes—a total of 64 bytes. The security vulnerability lies in the fact that this 64-byte data (the concatenation of two hashes) could be confused with a 64-byte transaction. For example, an attacker could create a Bitcoin transaction that is exactly 64 bytes long to mislead or trick a light node into confirming an incoming payment. We will explore some of the steps involved in this attack below.

A diagram of the Merkle tree in a Bitcoin block.

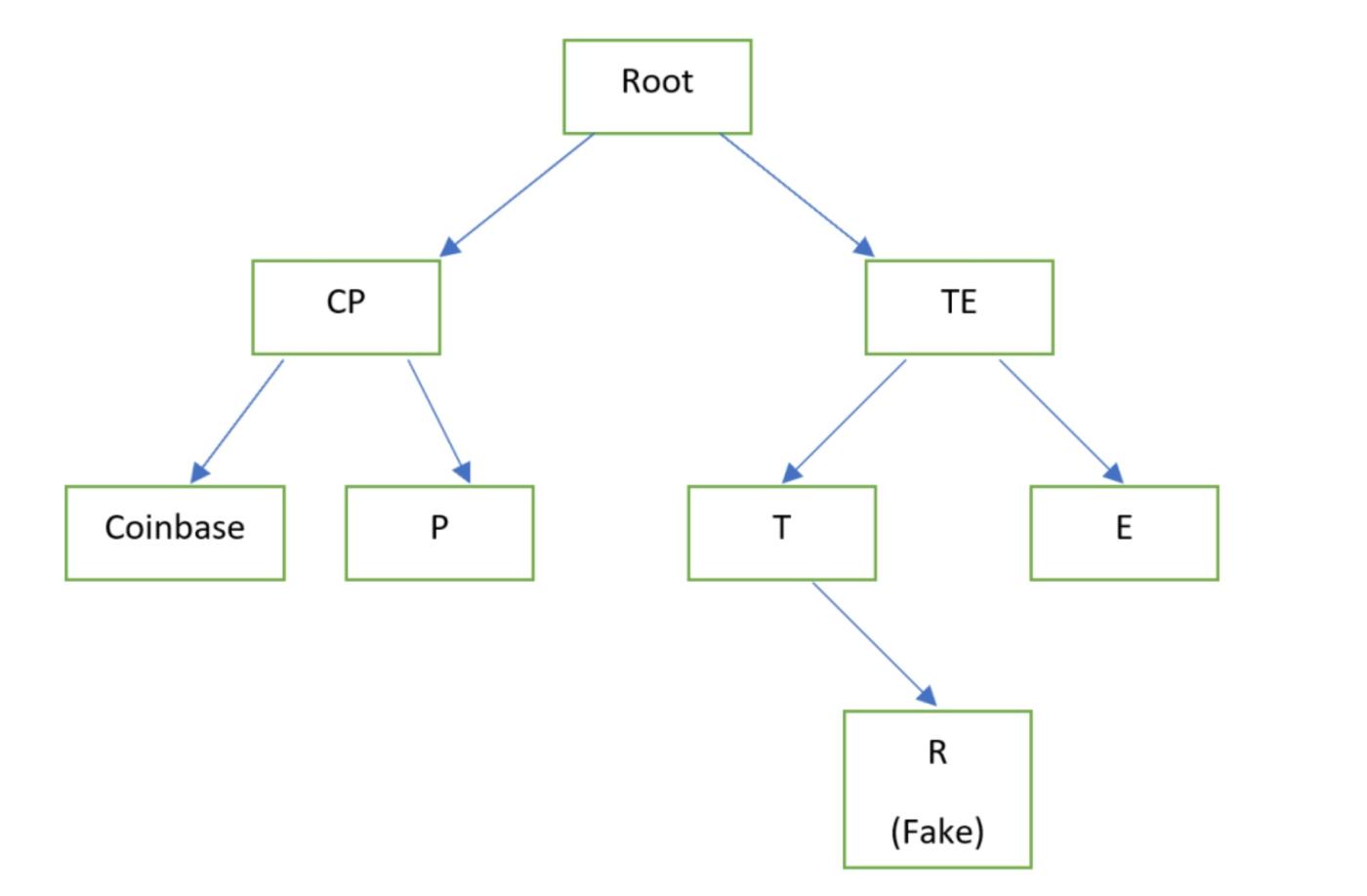

Map by Sergio Lerner : Location of fraudulent transactions

Overall, we believe the risk associated with this vulnerability is moderate to low due to the complexity of the attack; this contrasts with the "time warp attack," which we consider more serious. Nevertheless, it remains an interesting vulnerability and deserves to be fixed.

Hiding the ID of one transaction within another transaction

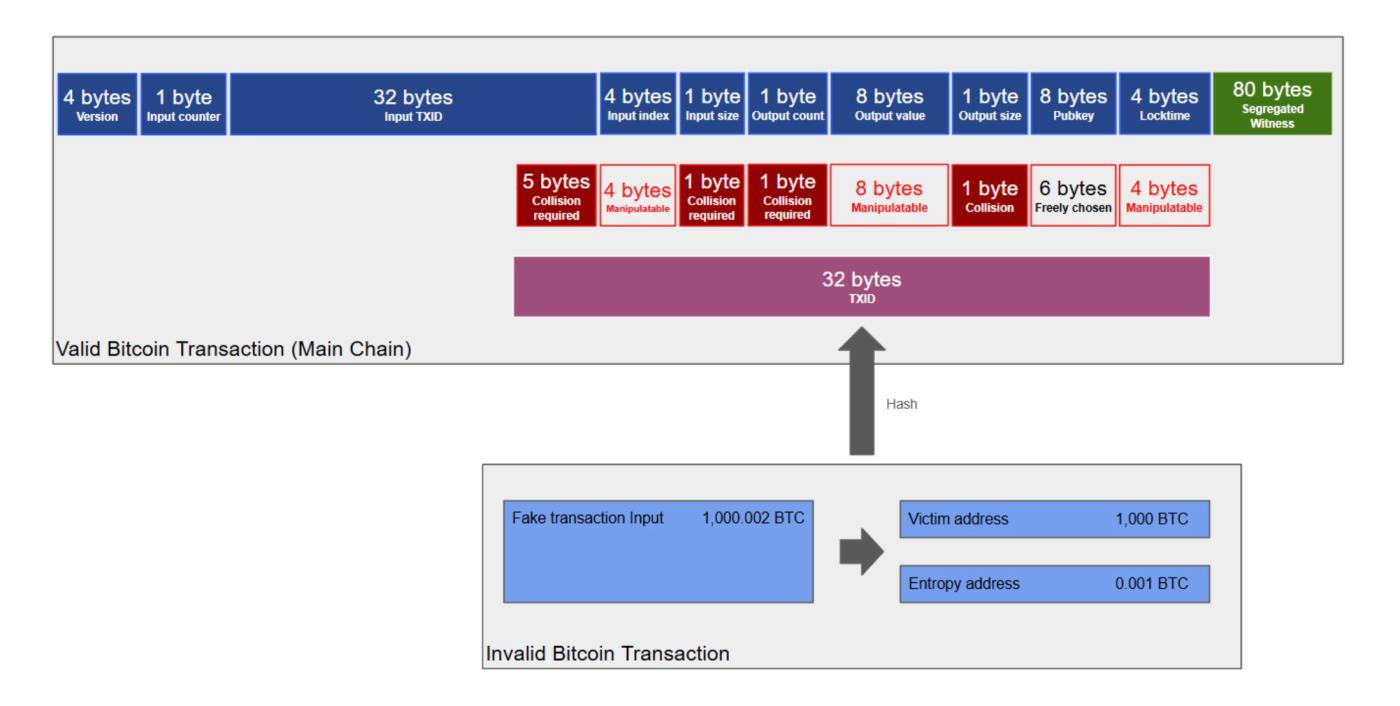

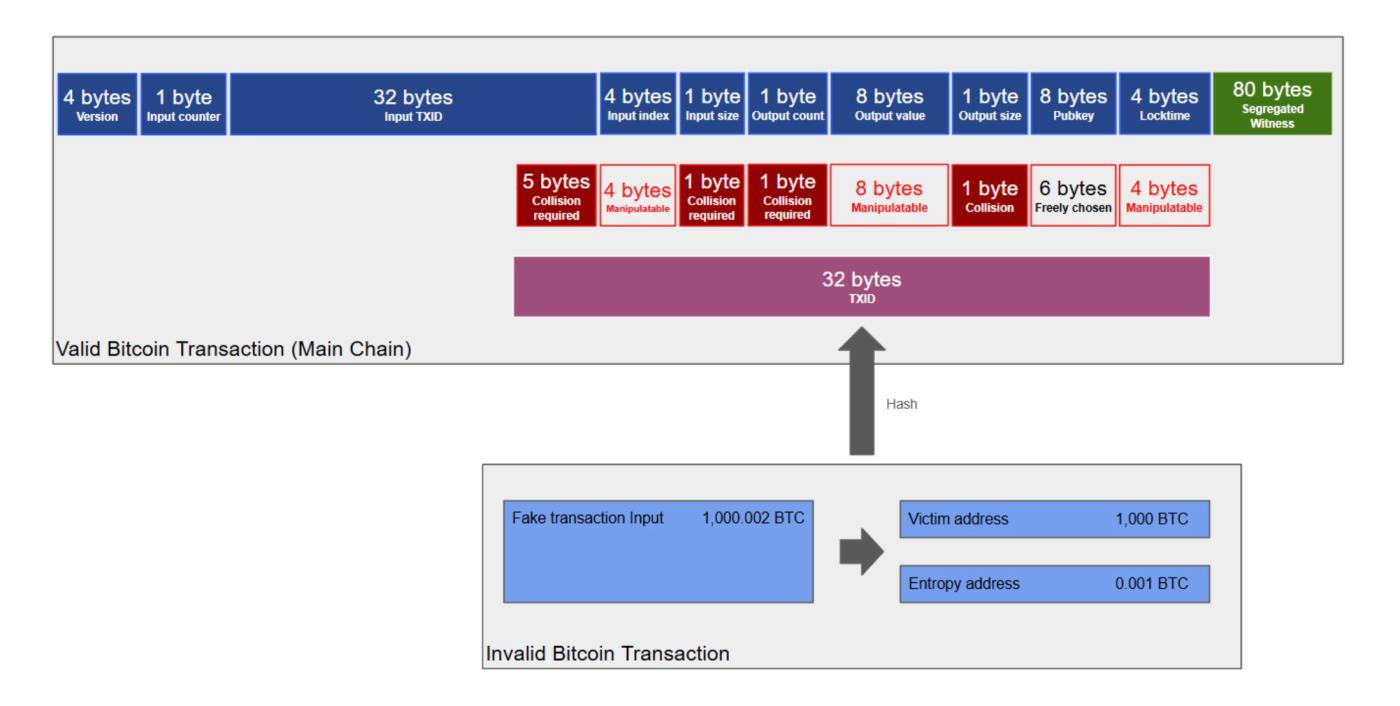

The most serious known attack exploiting this vulnerability involves tricking someone using a Simplified Payment Verification (SPV) client into confirming an invalid incoming transaction. We have provided a diagram below summarizing this attack. The attack steps are as follows:

- The attacker created a genuine, valid Bitcoin transaction that was exactly 64 bytes long. This number excludes any segregated witness data.

- The attacker then creates a fake, invalid Bitcoin transaction, sending (say) 1000 BTC to the victim. For example, the 1000.002 BTC in this transaction comes from a fake input that does not exist in the UTXO set.

- The attacker assigns a change address to this fake transaction, and then uses a brute-force search, constantly switching change addresses, until the TXID (32 bytes long) of the fake transaction is exactly the same as the last 32 bytes of the real valid transaction (64 bytes long).

- Once such a pairing is identified, an attacker can send SPV proof to the victim's light client, containing a valid path from the genuine block header Merkle tree root to the fake transaction. The victim will mistakenly believe that the bottom layer of the Merkle tree is the penultimate layer, with another transaction below it. The victim will then believe they have received 1000 BTC—proof of work from the miner being used by the attacker to deceive the victim. Of course, full nodes will not be fooled in this way (for many reasons), but SPV nodes will be.

The two transactions used in the illustrated attack

- Note: This attack was explained in Peter Todd's article published on June 7, 2018 , and Sergio Lerner's article published on June 9, 2018, respectively. -

The attack described above appears computationally infeasible because it seems to require finding a complete 32-byte SHA256 collision case. We already know this is computationally infeasible, and it's clearly easier to fool an SPV client by mining a fake block (which would require 2^84 searches today) than to find a hash collision with 2^256 searches. However, the trick here is that 64-byte transactions are adjustable, so you don't need to match 32 bytes through pure brute force.

The last 32 bytes of a 64-byte transaction

| object | describe | length | The length required for a brute-force search |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enter TXID | The hash of a preceding Bitcoin transaction. Therefore, it is random and cannot be manipulated. Brute-force search is required. | 5 bytes (in the latter half of this field) | 5 bytes |

| Input Index | One approach is to create a starting transaction (as a preceding transaction) with thousands of outputs. This allows the input indices to be manipulated to collide with (to some extent) fake transactions. However, this could be expensive and difficult to construct. In reality, some brute-force search might be necessary here as well. | 4 bytes | 0 |

| Input length | It's difficult to manipulate because there are other constraints on the transactions. Therefore, brute-force search is required. | 1 byte | 1 byte |

| Output quantity | A transaction can only have exactly one output; otherwise, it is unlikely to be exactly 64 bytes. | 1 byte | 1 byte |

| Output value | An attacker can send as many Bitcoins as they want, as long as they have that much money and are prepared to abandon it. If the input to this transaction is worth 1 BTC, then there are 100 million possible output values (100 million satoshis equal 1 BTC). Therefore, this field is (to some extent) manipulatorable. However, it might take burning 21 million BTC to fully manipulate this field. | 8 bytes | 0 |

| Output script length | It's difficult to manipulate because there are other constraints on the transactions. Therefore, brute-force search is required. | 1 byte | 1 byte |

| Output script public key | Because the funds injected into this transaction are irretrievable, this field can be easily manipulated. | 8 bytes | 0 |

| Lock time | The lock time can be manipulated, for example, expressed as a block height, with a maximum value of 500 million. Therefore, there is a large amount of entropy here. | 4 bytes | 0 |

| total | 8 bytes |

Therefore, based on the table above, under the most favorable conditions for the attacker (using all manipulateable fields), the attacker only needs to find 8 bytes of collisions. 8 bytes, or 2^64 searches, does not require many computing resources; a typical laptop can complete this quickly. In fact, it may require slightly more than 2^64 searches because none of the fields mentioned above are fully manipulated.

However, this attack isn't as severe as it seems. It's extremely complex to set up, potentially requiring a startup transaction with thousands of outputs and burning through thousands of dollars, all for the sake of manipulating just a few bytes of entropy. Furthermore, SPV wallets aren't as prevalent anymore. Those expecting to receive high-value payments are aware they'll need a full node to verify incoming payments. Nevertheless, this attack remains feasible, especially with the tools readily available, making it worthy of attention and prompting us to explore mitigation measures.

Merklegen hash collision

Another related Bitcoin vulnerability was discovered and fixed in 2012. This vulnerability involved two different Bitcoin blocks, one valid and one invalid, that could have the same Merkle root hash. Several things could cause this, one of which involved confusing a 64-byte intermediate hash step with a 64-byte transaction.

The core issue is that Bitcoin nodes store the block hashes of invalid blocks to avoid verifying them again (a waste of resources). However, if two blocks have the same block hash, one valid and the other invalid, a Bitcoin node (which, having verified the invalid block first, can no longer verify the valid one) might be tricked into abandoning the chain with the most proof-of-work and following a rival chain with less proof-of-work. This problem was fixed in 2012 by requiring nodes to perform an additional check before caching the hashes of invalid blocks.

A related vulnerability resurfaced in 2019 when Bitcoin developer Suhas Daftuar noticed that a similar bug had been unintentionally reintroduced in Bitcoin Core 0.13.0 (released in November 2016) and subsequently fixed in February 2017. Other vulnerabilities also relate to the issue discussed in this article; there may also be undiscovered exploits.

Proposed solution

Fixing this issue doesn't require a soft fork, at least not for exploits that spoof SPVs. The methods used by SPV wallets could be upgraded, for example, by always checking transactions at the same Merkle tree level as those transacting with Coinbase. However, the problem is that SPV wallets haven't done this, and understanding of this issue is limited. Therefore, people remain vulnerable.

Currently, the proposed soft fork solution is BIP 54, which completely prohibits transactions that are 64 bytes long after the witness data has been stripped. This sounds like a very simple and easy fix. After all, there seems to be no reason to create a transaction that is exactly 64 bytes long. For example, in our example above, it was the funds being poured into a black hole that created the 64-byte transaction. Suhas Daftuar noted in a 2019 email that he scanned the entire Bitcoin blockchain and found no transactions that were exactly 64 bytes long. This should make the soft fork smoother and easier to reach consensus because it prohibits something that has never happened before, and is therefore less risky and less controversial. However, today, there may be some 64-byte transactions.

BIP54 will introduce a somewhat peculiar new rule for Bitcoin: transactions of 63 bytes and 65 bytes will be valid; only transactions of 64 bytes will be invalid. However, it would be better to impose as few restrictions on transactions as possible.