Aster & Hyperliquid Gaslight Perps Users And Regulators Alike

Introduction

Probably the oldest and most prominent theme in DeFi is that of faking the De. This goes by many names. Decentralization theater. CeDeFi. Training wheels. The idea is that you brand yourself as decentralized, eschew the compliance efforts required of centralized businesses, and then just run a centralized business under the hood. Often that business uses software for a lot of automation. Fair enough. But nearly every business in the modern world uses software to automate operations. The mere fact your business uses software does not convey any sort of legal protection. Automating parts of your workflow does not make you decentralized.

But we still see many platforms and products employing the tactic of branding as decentralized for legal reasons — normally to claim an exemption from licensing, KYC/AMl and other surveillance requirements — in the real world. This tactic resembles that employed by many people in other areas of web3 that try to claim exemptions from similar laws because they wrote some software when they are accused of crimes that do not require them to be software developers.

Recently, volumes on supposedly-decentralized perpetual futures exchanges are growing at an incredible rate. And the two largest such platforms are Hyperliquid — which blossomed first — and Aster which came into its own more recently.

What we are going to do here is very simple. We are going to prove, by looking at the publicly-visible portions of the Aster and Hyperliquid systems, that they are not decentralized under any definition that would not also render the CME, CBOT and myriad traditional derivatives exchanges decentralized by virtue of their heavy reliance on automation.

To start with: both platforms have administrator-controlled pause buttons. Anyone that subscribes to Frank Herbert’s Dune Law Review knows that the power to destroy a thing is the absolute control over it. But maybe you want more detail. Maybe you think, contrary to all legal precedents in both our universe and Herbert’s, that a pause button “for safety reasons” is somehow exempt from the normal rules. We anticipated that. So we are also going to detail a range of ways these teams can steal user funds. Broadly speaking, if the team can help itself to the money you deposit into their system then the team has control and the system is not decentralized.

Stop and think for a moment how a bank works. Imagine you are the CEO of a bank and you decide you want to steal some depositor money. Probably you do not want to just shutter the operation for a few days and show everyone a 0 balance when you reopen. That is not particularly clever. Also, assume this is a so-called “digital bank” without any physical branches. You have no banknotes to steal. Ergo you cannot steal any banknotes from the safe or till or cabinet.

So what do you do? All the client money exists as records in your databases. You are going to need to get someone to write software that manipulates the records in those databases to reallocate funds to you. Or maybe your plan is to leave client accounts as they are and simply transfer corporate funds out in a way that an audit or reconciliation or something will find. So now you need to effect irregular transfers out of your corporate and reserve and such accounts to other banks. That is also going to involve software and entering records and you know it will trigger alerts whenever someone checks if the books balance. You are still a thief even if you expect the theft to be detected quickly.

Below we are going to describe “attacks” that look very much like those narratives. Attacks where the team unplugs and replugs software in unexpected-but-perfectly-workable configurations to take the money. Or attacks where the team uses a privileged position to disconnect some external access while they submit carefully-crafted commands into the electronic recordkeeping systems. Or maybe the team just seizes some of the platform’s funds in a way that is immediately visible and would raise alarms but, still, gives them the money. All of those attacks are morally, and legally, identical to the insider bank thefts described above. The precise details differ because the software differs (a bit). And that is why, we argue, these systems are both as centralized as traditional platforms.

The analysis for each platform is a little different. Aster is new and running through the API, and a few related audit points, is pretty much sufficient to prove centralization. This is mainly because Aster operates in large part in public view with a lot of visible controls. An admin interface sufficient to take user deposits is publicly visible on Aster’s smart contracts and it is straightforward to explore and, for the team, to exploit. Hyperliquid is different. Hyperliquid exposes only a tiny slice of the system to public view. So we are forced to examine that which is exposed in great detail to evaluate the system. But in the end we are able to prove team central control in both cases.

We have separately published that work for Aster and Hyperliquid. If you want to see proof our claims are true go read those. For now, you can also just accept the claims are true and read on for a discussion that does not depend on the technical details of how and why our claims are true. Of course we want you to read our analysis and verify it for yourself. Nobody is discouraging you from reading and considering those two pieces. But the discussion here covers more important market, regulatory and legal topics that do not depend on the details of those analyses.

Discussion

We make some strong claims here. But to be clear: these are not hand-wavy arguments mixed with a vague appeal to authority and an overbroad claim users are being lied to. We make specific claims, referencing specific publicly-visible code, data, and documents. Yes, some parts of these systems are obscured from public view. But we do not need to examine, or publish information from, those parts to prove central control. The entire point of this exercise is that we are already sure how these work before the team bothers to respond because we can see the operations in public. That was supposed to be the point of all this blockchain and smart contact stuff.

It is also clear that these faux-decentralized perp exchanges have “won” when it comes to volumes. We cannot be completely sure why this is so because, well, markets are complex and examining data is rarely sufficient to prove the outcome of the collective decisions of millions of market participants. So we have to guess. But the guesses here are not complex. Why might these products claim to be decentralized? Almost surely because decentralized products do not face prudential regulation and they do not need to implement AML/KYC. Decentralized perps exchanges are cheaper, simpler and easier to run than centralized ones. And they can take more customers. Note that does not mean decentralized platforms are necessarily cheaper and easier to design or build or for franchise development. But prices are set at the margin. What we care about now, given these things exist, is how they behave in the competitive market of trading platforms.

To some extent those cost savings should be offset by the costs of running decentralized infrastructure. But of course these platforms manage to avoid those costs by only claiming decentralization and then running lower-cost centralized systems. There are no complex governance dynamics and no complex machinery to handle catastrophic events when a single entity can press the pause button or steal all the deposits.

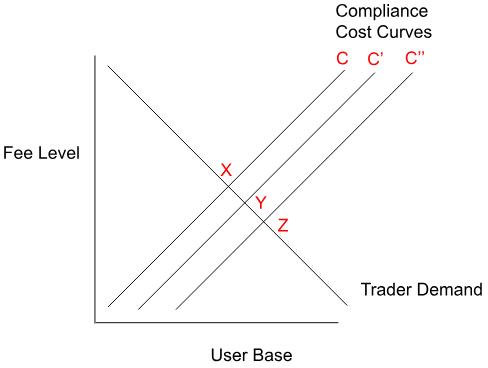

We can model this using simple, standard, economic concepts. Anyone that has taken international economics, or trade economics, or maybe macro II or similar has seen this kind of chart:

This is, roughly, the standard analysis to explain the concept of gains from trade. The ideas go back at least to David Ricardo in the early 19th century and the framework — comparative advantage and the resulting potential for gains from trade — is accepted by everyone. You cannot look at the past few millenia of human economic experience and reject this one.

To start, assume C is the cost curve to run a compliant exchange. Not just the cost of running the technology but the cost of running the technology and all the other stuff needed to achieve compliance. Then imagine C’ is for an exchange that increases automation but keeps the additional controls needed to remain compliant. This plausibly allows you to run at a lower cost which expands the user base. Why? Because there is more demand to trade when prices are lower. That’s the “trader demand” line here which plays the role of a standard demand schedule. Then C’’ is an exchange that cuts costs by just running simple centralized trading infrastructure and cutting all the additional compliance costs. This captures more demand because it is cheaper. You can think of the move from C’ to C’’ as firing the compliance department and then changing the onboarding form to make all fields optional and always accepting applications.

Simply moving from C to C’ to C’’ is not innovation. You can get all the software you need to, mechanically, run all kinds of exchange products for free off github. You can bribe the owners and managers of an offshore bank to process your in- and out-bound wires without properly screening them. And you can run a bunch of servers — cloud, on-prem, whatever — to support your exchange cheaply. None of this costs billions of dollars. Ex the bribery and bank fraud bits none of this costs millions of dollars.

Go back, look at the early crypto exchange costs, and then remember computers got about 1000x faster since Mt Gox was founded 15 years ago. Mt Gox did at most 10s of trades per second. It was not a quality piece of technology even for the 1980s.

You could probably run Mt Gox today on a mid-level Raspberry Pi over a reasonable mobile data connection. There is no innovation in running your exchange cheaply and ignoring the law. Or, rather, it is the same “innovation” in the business idea to become a drug smuggler. Not all profits come from running a better business.

In trade economic terms these faux decentralized exchanges generate a massive consumer surplus. That is a fancy economist way of saying the users gain because they pay lower prices. And some users that could not transact at all before can now trade and therefore realize gains from trade. This is why users like platforms like Aster and Hyperliquid independent of whether they are compliant or legal or openly washing money for terrorists or whatever. If Z is sufficiently far below X then enough traders will ignore how the exchange is getting from C to C’’ and whatever side-effects that shift may involve. Are these traders complicit? Are they naive third party beneficiaries? Are professionals operating on these platforms willfully blind co-conspirators? These are complex questions. We are not addressing the question of platform-user responsibility here. Our focus is on platform-operator liability.

To some extent this is also a “market for lemons” problem where naive users believe exchange claims of compliance and therefore do not even see that negative externalities might exist. Or, because users do not care about compliance, there are no providers still offering compliant platforms because they’ve all moved on to an area where people will pay for compliance.

If users cannot, or do not care to, distinguish between compliant and non-compliant exchanges they are going to go with whoever offers C’’ over C because on the basis of the thing they can see and surely do care about— price — C’’ is strictly better. Akerlof’s market for lemons example involved information asymmetries faced by consumers looking to buy used vehicles. And his key insight was that in the presence of significant information asymmetry sellers of good products — quality used vehicles for him, compliant exchanges for us — may simply exit the market because nobody will pay the required premium for their product since they cannot distinguish between good and bad.

Traders, similarly, will trade wherever is cheapest. It is not really their problem if the exchange breaks the law. This is why enforcement against exchange operators exists. If the exchange operating at C’’ is non-compliant then all of the fees the operators collect are, again in trade terms, “producer surplus.” The owners collect substantial economic profits. All those profits may be illegitimate but that does not matter if the operators get to keep them. It is the regulator’s job to allow shifts from C to C’ and C’’ that are accomplished through innovation that follows the law. And it is the regulator’s, and law enforcement authorities’, jobs to remove non-compliant operators offering lower-cost trading off C’’ that does not comply with the law.

If the government cannot distinguish between compliant and non-compliant products then we have a particularly awful market for lemons problem where the information asymmetry is between the exchange operators and the police. Then the “winner” is whoever can better befuddle the government and nobody should ever make a legitimate attempt to comply because curves from C and further left are not going to find any customers. Akerlof’s work tells us that, in such an environment, there will be no compliant exchanges. In a literal sense regulation will cease to matter because nobody offering services anybody uses will make an attempt to comply with the rules.

These platforms are “winning” because they are playing an unfair game. They can take clients from anywhere without compliance expense or geographic limitations. Yes, the platforms may claim to do screening. Sure. We are not even claiming they have no compliance costs. We are simply claiming that because all of that compliance is voluntary, and they are not participating in any sort of mandatory reporting regimes, those costs are going to be wildly lower than for a legitimately compliant business. This is not about efficiency or innovation. Competition is about a group of participants running a race under a single set of rules. A mediocre athlete could out sprint anyone to 100 meters at the Olympics if they and they alone were riding a bicycle.

Beyond cost, these platforms are also attractive to end users because they can offer more leverage, and looser terms, than properly-run platforms. If you eschew all regulation based on a false claim of decentralization you can probably put together a front-end that meets the needs of degenerate gamblers everywhere. And if you then compete with platforms that pass traditional regulatory muster you are going to win. All of this is explained by the simple trade economics chart above.

It will continue to all be fun and games until there is a problem and the authorities decide to notice these platforms were never decentralized to start with. And on that front there is a huge difference between Aster and Hyperliquid. Hyperliquid, and the associated HYPE token, is roughly a standalone ecosystem. The token will rise and fall with the perps platform. But Aster is tightly linked to Binance.

This will drive different outcomes for the platforms and the tokens. HYPE fails like LUNA while ASTER fails like FTT. The former is far more straightforward to zero: you just need to kill the perps exchange somehow. That may or may not be easy but it is a single attack point that will ~100% work. And there is no other narrow way to send HYPE to zero. Aster, on the other hand, has a lot more ways to fail and zero. But it is also part of a far larger, more heterogeneous and to-date-more-robust ecosystem. Bluntly: if the Hyperliquid platform starts to collapse it will probably burn all the way down to nothing. But if Aster gets into trouble Binance will probably press pause, send in some more money, and keep the thing alive as long as it can.

Eventually this will be a problem. Or, to quote Mr. X’s wonderful monologue at the beginning of Layer Cake “It is only very very stupid people who think the law is stupid.” And it is well known that the law can be slow, most commonly captured in the saying “the wheels of justice grind slow but they grind exceedingly fine.” The point being that the law will figure this out and slowly work through violations at some point. But that modern saying is an odd re-rendering of Plutarch’s concern that “So that I do not see what benefit there is in those mills of the gods that are said to grind late, since they obscure the punishment, and obliterate the fear of evil-doing.” The ancient sentiment is closer to “justice delayed is justice denied” with an element of “crime pays if you can avoid extradition.”

We are watching a small group of egregious outlaws talk past and bribe regulators so they can continue to collect a massive producer surplus based entirely on false premises. Part of the strategy also appears to be getting close enough to a sufficiently large number of government officials that enforcement is too embarrassing to pursue and the operators can keep all their gains from trade. Users — some retail, but some large institutional and powerful firms as well — are also in on this because they, too, gain from the trade sketched out above.

But not everyone wins. For any compliant exchange operators out there — or, say, large listed financial services businesses looking to get into web3 perps — a delay in enforcement is a direct attack on their bottom lines because crime is paying for their competitors. Given the political power of many large exchanges and their publicly-stated desire to attract “institutional” business one would expect a lot of pressure for enforcement here. There is also the question of self-preservation for the authorities in that simple and well-understood economic dynamics here will render them surplus to requirements in short order unless they do something.

Faking The D In DEX was originally published in ChainArgos on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.