I sat down with President Mary C. Daly, President and CEO of the San Francisco Federal Reserve, and President Tom Barkin, President and CEO of the Richmond Federal Reserve to talk about the current state of the US economy as we go into 2026. We look back to the past, particularly the 1970s and the 1990s, to understand what those periods can teach us about inflation and policy decisions today. We also talk about the persistent uncertainty we are facing in geopolitics and technology, and the growing gap between the economic data and how people feel. We talk about the headwinds we are facing and the tailwinds to be excited about. And finally, we spend time on what’s often missed in these conversations - the sources of resilience and the reasons that there is still room for optimism.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and flow. Above is the audio version, which is also available wherever you listen to podcasts.

This is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Recorded on Wednesday, January 6th, 2025

What Can We Learn from the 1970s and the 1990s?

Kyla: President Daly, a lot of people are looking to the past to try and find some answers around the future, and you recently wrote a blog post talking about the push and pull that we’ve experienced with the 1990s and 1970s. A lot of people are pointing to those times as comparison points. What do those two decades teach us about what we’re going through right now?

President Daly: People refer to those two decades often because they’re in our living memory. Both were periods when inflation was above target and we were worried about how monetary policy should respond.

In the 1970s, policymakers saw a weakening labor market and worked to offset it, but they missed a very important component of the economy, which was a productivity growth slowdown. The result was well known. We had very high inflation and it took the Volcker disinflation to bring it down. That’s a period we definitely want to avoid.

The 1990s was a period when we also had above target inflation, around 3%. But policymakers decided to wait and not raise the policy rate to offset it because they saw the computer coming out and wondered if that was going to spur productivity growth.

Productivity growth can spur the economy so we can grow faster, but it’s not inflationary. In fact, it often brings inflation down. You put those two decades together and it really dovetails what we have. We have above target inflation. We have a slowing labor market, and we have AI, which looks like it could be a productivity boom, but we don’t know yet. History doesn’t repeat itself exactly, but those two decades show us the span of things that we have to consider as we navigate the future decade ahead of us.

The Importance of Inflation Expectations

Kyla: Are there any key warning signals that people can pay attention to that would drive us toward a more 1970s outcome than a 1990s outcome?

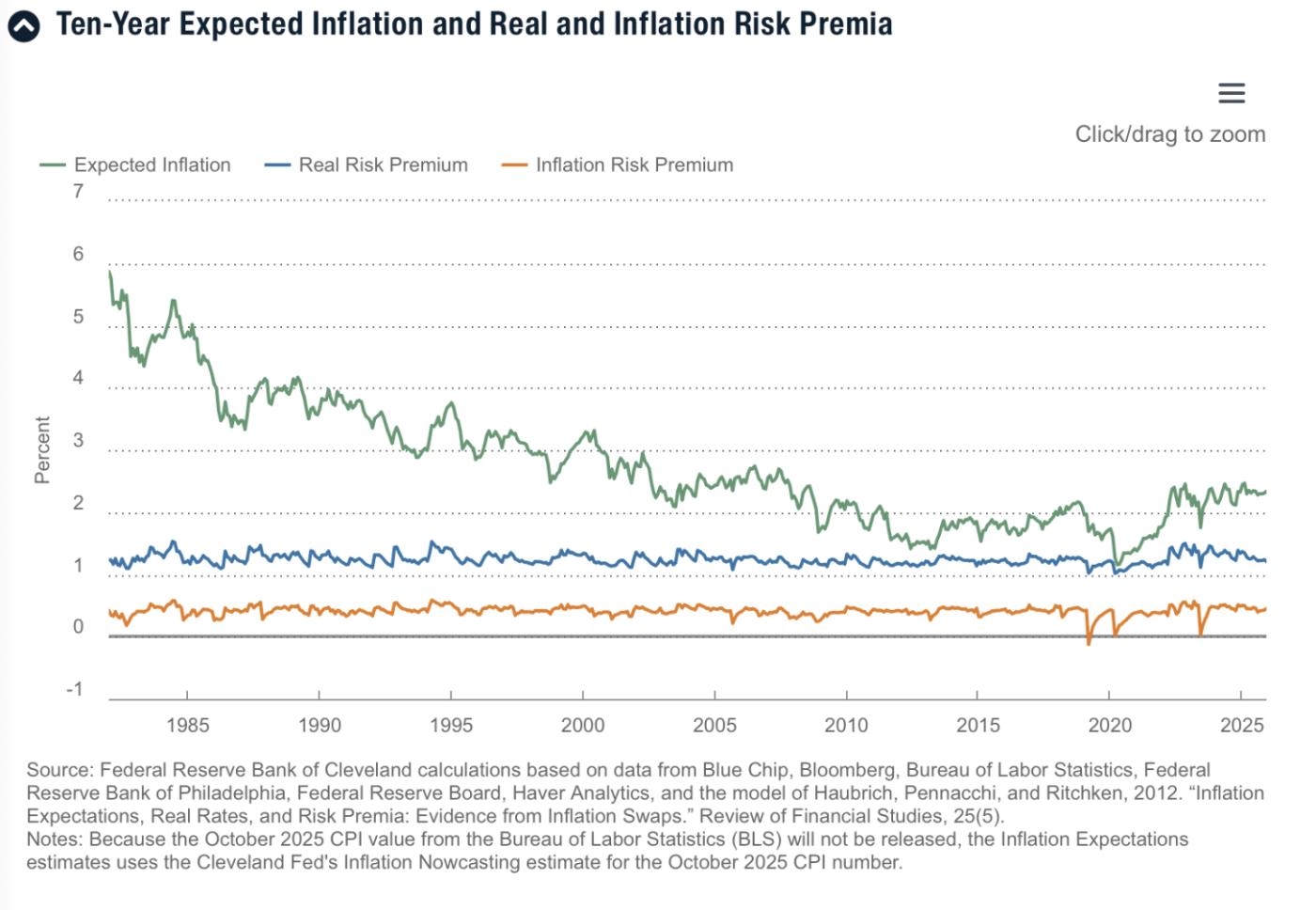

President Daly: Absolutely - you can look at inflation expectations. That is something that rose rapidly in the 1970s as inflation rose, and it was really hard to bring it back down. So people expected high inflation and that contributed to inflation continuing to be high.

We certainly experienced our version of that in the post-pandemic inflation runup. Inflation expectations of the short and medium frequency rose and that was very worrisome to policymakers because that’s a sign that we’re losing credibility. We want to make sure we have that. So we went out and we took aggressive action and we reiterated countless times that we are determined to bring inflation back to 2%. And of course today, inflation expectations are very well anchored at the medium and longer run. They’re barely moving, and I think that’s important as we navigate forward. But we need to keep an eye on inflation expectations.

How Do We Navigate the Age of Uncertainty?

Kyla: President Barkin, what is the modern version of the uncertainty of the 1970s and 1990s today? Is it AI? Is it tariffs? Is it immigration? Is it something else?

President Barkin: I think it’s actually the persistence of uncertainty. If you take a step back, let’s just go to the 2010s and you say: what was inflation in the 2010s? It was somewhere between 1% and 2% every year. What were interest rates in the 2010s? They were somewhere between 0% and I think the peak was 2.5%. What was happening in geopolitics? It was pretty stable. It was pretty stable, frankly, since the Berlin Wall came down. How about regulation? Imagine being a wind farm manufacturer now back from one administration to another and the technology came through, but the adoption curve was relatively slow compared to what we’re seeing more recently. I just think you’re going to have higher volatility, higher uncertainty, and that’s going to be a persistent part of the economic environment.

People are going to have to do things about that. It’s not like that’s never happened before, but I actually look back in the last 40 years and I think that was relatively stable compared to the environment we’re in and are likely headed toward.

Kyla: What does that mean for the everyday person? In the last 40 years, you had the growth of suburbia, you had the growth of the white collar jobs - it seemed like everything would be stable for a very long time. How can the average person think about this rise of uncertainty?

President Barkin: I think if you’ve got more volatility and more uncertainty, you may want to have a few more assets in your pocket to help you deal with it. I think if you’re running a small business or even a bigger business, you want to be thinking about multiple options. A good example is I talked to lots of companies who have their entire supply chains in China, and you go right now, wow, when did they make that decision? I mean, at what point did that seem to make a lot of sense?

You could say the same thing about Germany having its natural gas all coming from Russia. When did that make sense? Well, there was a time where it did, but maybe now we’re in a time where you want to have multiple vectors, multiple options, multiple irons in the fire, given the risk that things are going to change.

Is AI the Future?

Kyla: President Daly, when you look back to the 1990s, do you feel like AI can be what the internet was for the economy back then?

President Daly: It’s really hard to say at this point. Some people would argue it’s going to be much larger than computers and the internet, and that it’s going to be electricity and the steam engine. I think there’s a lot of views out there, but we really have to collect more information. What I see that’s similar in the computer revolution and the internet revolution that led to the productivity boom of the 1990s is that people are using it.

We don’t usually see it in the data until well into the using it stage. Firms are starting to experiment. Many firms are using it for their various types of operations, but we’re in very early days. I think to just assume that it’s going to be computers or it’s going to be electricity, we need proof of that.

There’s certainly something there. I just don’t know the scope of it, the magnitude of it, and the timing of it. I’m not an enthusiast, but I’m also not a doomsayer on this. I do think people are rightfully asking, how will my job be affected by this? So it’s causing worker insecurity in a way that does remind me of the computer age. There was a lot of worker insecurity in the 1990s. People were nervous about their jobs. They were nervous that technology would take them. But President Barkin referenced periods of history that if you go back to when manufacturing floors were being automated, steel workers were nervous about their jobs and car manufacturers were nervous about their jobs.

So we’ve lived through these periods of extreme anxiety about technology taking employment. What’s different this time around is that tech workers are worried about it and not your manufacturing workers. I think that is a different group of people that is often younger and often have not experienced a period of volatility as President Barkin said, or a period of the sort of job loss that could affect them. But so far we’re hearing most of our firms in the 9 Western states, the 12th district, they’re augmenting their workforce, not replacing it with AI.

No One Likes Inflation

Kyla: President Barkin, the economy is very strong on paper, but when we look at consumer sentiment, it’s struggled, especially since about 2022. You’ve talked a bit about your confidence in the economy even during this year of uncertainty. When you see that mismatch between sentiment and economic data where people are feeling really bad, but the economic data is good, what do you think is driving that?

President Barkin: I think historically there was a pretty good correlation between consumer sentiment and consumer spending. If you felt good about the economy you spent, if you felt bad about the economy, you didn’t. That kind of got unbound in 2022. We saw very weak consumer sentiment with still very strong spending. And I think 2022 is very clear, that was inflation.

It turns out when prices go up the way they did in 2022, people don’t like it. The point I keep making is we all have rediscovered how much we hate inflation. Frankly, it’s just exhausting for folks to receive a price and think that’s too high and then know you’ve got to go shop it around and negotiate. Or if you’re in a small business and your supplier comes in there and you’re trying to go to another source, it just takes a ton of work and it really wears people out.

I think that had a huge impact on sentiment in 2022. So now we’re in 2026. Consumer sentiment is low again, and spending still seems to be relatively healthy.

Part of the story continues to be prices. Maybe it’s not inflation as much as it is just the price level. Will I be able to afford a house? Why does this stuff cost so much? It may not have gone up so much year over year, but it’s still high from recent memory. I’ll just remind Mary and I that in the 1970s our grandparents told us that Cokes used to cost a nickel and, and they did use to cost a nickel, but that was like 50 years ago, and my grandparents were ancient, but who cares? But today it feels like Cokes cost a nickel three days, three years ago. It’s just so recent. So that’s part of it. So that first part I know to be true.

The second part, I’m just speculating, but every time I walk out of a meeting, I pick up my phone. On that phone are a bunch of notifications. And the notifications are all negative. It’s tariff, tariff, tariff, tariff, tariff. It’s Venezuela, Venezuela, Venezuela. It’s whatever the news of the day was. No one says another great day for the US economy in those notifications. I do think that brings people down. It was true when it was inflation. It’s true. It’s tariffs. It’s true with the pace of change today.

I think that’s got an effect on sentiment as well. Spending continues and I think you have to then get to the dynamics of spending, which is unemployment on a historic basis is still pretty low. 4.6% is the lowest it’s been in the last 50 years, other than the late 1990s, the late 2010s and 2007 - so still relatively low.

People have jobs, wages are up, and the stock market’s healthy. So people have money and even though they don’t feel good about it, they’re still spending.

How The Stock Market Might Influence Spending

Kyla: You had an interesting anecdote in your 2026 outlook where you quoted a local restaurant that saw a foot traffic decline if the stock market declined on that day. So essentially, stock market performance and consumer health might be pretty closely tied together. A lot of spending is driven by higher income consumers. So when you think about that disparity, how does that frame how you think about the economy?

President Barkin: Well, there’s no question it’s true. If you look at Darden Foods, for example, and look at their high-end brands like Capital Grill and compare it to their lower end brands, the spending’s much higher there.

If you talk to the airlines, they’ll tell you the front of the plane is full and the back is not. The hotel brands experience the same kind of thing. So wealthy people have money, asset values are high, they’re spending more. I will say the lower income people are still spending but importantly, they’re choosing.

I talked about how frustrated people got with inflation. People are still very frustrated with high prices, but today they have, I’ll call it the emotional room, to do something about it. In 2022, you just took it. That’s not what’s happening today. People are going to Walmart, going generic, postponing a vacation.

They’re taking action. That’s the big difference I’d say. Wealthy people, they’re spending, and depending on how wealthy they are, they’re not doing that much negotiating. But the lower income people, they’re still spending, but they don’t want to spend on stuff that’s been priced up. They’re making choices.

Central Bank Communication and Feedback Loops

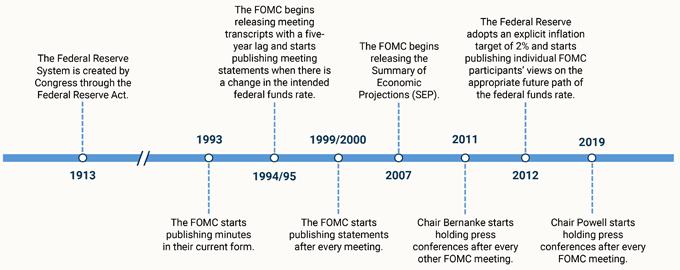

Kyla: President Daly, the Bank has become much more open in communication. You had a great infographic talking about the increase in transparency of the Bank, but you’ve also talked about the importance of being open to change, the importance of nimbleness. How do you think that the Bank can be more nimble and willing to change?

President Daly: I really do think we need to be more nimble. One of the places I’ve been giving a lot of thought to is this concept of what language do we use to describe things. We are committed to communicating and we work really hard to do it well. Then we had a term data dependence, which started in the post-financial crisis period when markets and regular people thought, “Hey, we’re going to just be on a preset course. As the economy gets out of a ditch, we’re going to start raising the interest rate off the ZLB - off the zero lower bound.”

So we policymakers put that term together because it was important for that moment. Now roll forward to today, we’re still using that term, but what it means to people is something quite different than what we intended originally because the context has changed. So now, largely from how the media thinks about it, how commentators external to the Fed use it, they often mean data point dependent and everybody waits for the next CPI to come out and says, “well, that’s what the Fed’s going to do.”

But we know as policymakers, we’re forecast based. We’re not data based from last week or last month. We look at the forecast and the inputs go into the forecast, but it’s really how the forecast evolves. I think that’s an example of where language which was once helpful can end up being a bridle. So just holding ourselves to the agility to communicate the right language at the right moment.

Transitory is a word that nobody wants to use anymore. I don’t think we should strike it out of the dictionary, but it really overstayed its welcome and we ended up carrying that around and sort of forbidding its use after that. I do think language is important and you can’t think that something you did 20 years ago still holds today as the right communication device.

Another place where I think I’ve given a lot of thought on agility is that - we have this balance sheet tool. We understand in detail what the balance sheet is doing and why it’s not doing one thing, it’s doing this other thing.

But the public often doesn’t understand that. And just speaking more loudly and more directly doesn’t really help. Giving people lots of details is not necessarily what they’re looking for. So committing ourselves to be agile, to respond to the conversation that’s in front of us as opposed to just reading out of the lexicon of the details, I think is really important for us.

So whether we’re talking about a tool or a communication phrase, I think just being agile enough to look ourselves in the face of the public, use the public as our mirror and say, “are we being clear and does the public understand what we’re trying to do?” And do they ultimately walk away trusting that we’re doing this work on behalf of them, which is the entire purpose.

Can I follow up with that, Kyla, on something Tom said, because it was really important. There’s research out there that says Tom’s observation is exactly right and that research comes out of the San Francisco Fed, but other places as well - people don’t think of things and then the media writes about them. The sentiment that the media reflects often gets translated into people’s views. So in the period where the commentators only talked about how high inflation was and how rapidly it would rise, people thought, “oh, that’s right.” And so the more negative news we get, the more that’s going to depress some sentiment.

We really have to be thoughtful about what people are getting. Then how does it make them feel? Then how does that create a divide? And that’s important for us as policy makers in my judgment, because if it’s otherwise, it’s like a loop, right? The commentators say it, the people feel it, that we respond to it. We end up in a loop that goes the wrong direction if we’re trying to create stability in a time period of uncertainty and volatility.

President Barkin: I like the idea of a loop because it goes back to nimbleness. We’ll do a forecast every quarter and talk about where we see the economy going and based on that, where we see rates going. And then there’s this loop where the commentators and the media and the markets decide we’ve just promised something. I’ll often go to meetings where someone will say, “oh, I guess you guys promised three more rate cuts this year” or whatever. And if you want to be nimble, you ought to say, this is a forecast, this isn’t a commitment. That’s a negative reinforcement loop that then makes things stickier as opposed to making you more agile.

President Daly: Absolutely.

Kyla: How do we best break that loop?

President Barkin: I think the Kyla Scan podcast is a good start.

President Daly: I look to young people whenever, whenever I think that we are getting ourselves in a ditch on something. I look to young people to say, well, this ditch is very uncomfortable. We’re only going to get out of it by looking up. So I’m with Tom here, the Kyla Scanlon podcast could be helpful to us, but maybe after 10 notifications of the gloom, we get something positive that says it’s a good day in America or a good day somewhere else. It’s a good day in Richmond, or it’s a good day in San Francisco. That would be helpful. I’ll just say this. Regional Fed presidents have spent a lot of time in their communities. That’s one of the virtues of having the regional Feds. When we’re out there in our communities, we’re not only hearing gloomy things, which is important, but people are also making business decisions. I count cranes because people might be gloomy, but they’re putting up cranes to build stuff, and that tells me something positive.

Non-Traditional Economic Indicators in the Age of Foggy Data

Kyla: That’s actually one of my favorite things to do when I travel is take pictures of cranes, because it is a really good regional economic indicator. Could you actually expand upon that? Because I read that in one of your notes and thought it was such an interesting point, how powerful seeing a crane is for the local economy.

President Daly: It’s very powerful. One of the things that I’ve learned in doing this job is that people might say they’re afraid, but the question you have to ask next to that is, what are you doing? And if the fear is influencing their behavior, that’s important to know. But one of the things that happened after tariffs were announced is I went to Utah and people were talking about them, but they were still putting up new cranes and they were working on existing cranes. Cranes are expensive, right? And it’s not just fixed cost. There’s a variable cost to this because you have to move the crane up and down. You’re still putting things together. They were still actively working these cranes and they were springing up all over. It just tells me that even in periods of time when people feel uncertain or the world is more volatile, good things still happen and people still make investments in their future. Might be different than what they would do if they were unconstrained by uncertainty, but they’re certainly still active. So other metrics I use too is when I’m worried about consumer spending, I go to parking lots of retailers and I don’t just go to the ones that wealthy shoppers go to, I go to the other ones and I look in their carts, what are they buying and how are they making decisions and how full are the parking lots? When they start to get worried is when the retailers are telling me there’s not accumulating inventories because they’re worried about demand and the parking lots have spaces up near the front of the store. Then you start to say, “okay, this is bleeding in.” Right now, I’m not seeing that. We have many months ahead of us to look in the parking lot.

Kyla: President Barkin, do you have any more non-traditional economic indicators like that you look at when you’re going to local businesses?

President Barkin: I do it a little differently, which is I like to take the consensus and go do small business roundtables and put the consensus on the table. So somebody will say, tariffs are going to drive up prices. Alright, let’s have a conversation. Who’s taking up prices because of tariffs? We have conversations about the labor markets ticked up, who’s planning layoffs - and the thing about layoffs is you don’t just do them immediately. You have to think about it. You have to plan it, you have to do a WARN notification if it’s at any kind of scale.

So you can tell two months ahead of time whether the sizable companies you’re talking to are planning layoffs or not. I ask people, in November, what your budget assumptions are for next year in terms of price increases and comp increases? So I take the consensus and then I try to sit down with a bunch of businesses and test it and it happens a lot that what’s actually happening is not at all what you think is happening.

President Daly: Yeah, absolutely. Tom, maybe you’ll agree or not, but I think that one of the values of being out in the region is the presidents across the entire US, all of us are out doing roundtables and other types of things, but we’re checking the common wisdom you have. We just had an FOMC and just made a policy decision, and then you come out and you think, is this what businesses are doing? Does our modal outlook really jive with what businesses are actually doing? And that’s why going back to Washington 8 times a year and talking to each other is so useful.

A Labor Market Driven by Healthcare; An Economy Driven by AI

Kyla: President Daly, one thing that has really come up in the economy over the past year is most of the job growth has been concentrated in healthcare and social services and most of the economic growth has been, partly due to AI. When you think about that dynamic, how does that make you think about the economy over the course of 2026?

President Daly: Well, if you do look at GDP growth, you see two things driving it, and the investment that’s driving it is really in AI and it’s in a narrow set of AI producing sectors, and that’s important for us to watch.

Data centers are contributing a lot to the investment. AI model makers are contributing a lot. That’s not a long-term sustainability play, but it’s certainly boosting activity at this point. On healthcare and social services, you shouldn’t really be surprised that healthcare is growing. The population’s aging at a rapid clip here, and so people need more services as they get older.

So that’s not surprising to me. And healthcare is a job. It is still employment. What worries people is the lack of diversification. Going back to what Tom said about diversification, you need a diversified economy going forward to ensure that you take in as many people as are being produced and who want to work.

Because not everybody’s going to work in healthcare. That’s where I think people are recognizing that the labor market really is slower than it was. In 2026, it’s quite possible to have GDP growth reasonably solid and have a labor market that’s just basically moving along, right? Not getting particularly far worse, but not getting much better. So I think that’s just a gap that can form when you have a new technology that people are excited about and when you have an economy with a lot of uncertainty.

Kyla: President Barkin, do you have any thoughts on that?

President Barkin: I’ll also make the point that the narrowness of the investment being driven by AI is also relevant to the stock market. I talked about wealthy people earlier, and wealthy people are spending more than less wealthy people.

If you believe that that’s being supported by the stock market, which I do, then you say, well, how narrowly is the stock market appreciation? You’ve got a set of tech stocks heavily indexed to ai. So one of the risks out there is the AI frenzy eases, and then if it eases, you’ve got issues with investment getting cut back and you’ve got issues with valuations getting cut back.

And if you say the two big engines of the economy right now are on the investment side, AI and on the spending side, wealthy consumers, you could see those two things going together. That’s one of the risks I’m watching closely.

Kyla: It’s a bit scary. It feels like it’s just one little domino.

President Barkin: On the positive side, there is a bunch of stimulus coming into the economy. Yeah. Monetary from what we’ve done. Fiscal from the, the tax bill last year is going to have big tax refunds this year that should help. Gas prices are down and that frees up money for people to spend. I don’t want us to be the iPhone here and only give the bad news. There’s also a good news version of this.

President Daly: I think the surprising part about the economy has not been its precariousness, it’s been its resiliency. Now, just think since the pandemic, the pandemic was going to break us, we’re on the precipice of decline because people were going to run out of their excess savings and then they were going to massively pull back. The job market was going to overheat and spur inflation.

These things that come as the grim predictions out of the environment we’re in just haven’t occurred. So that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t watch them, but I do think it’s important to be cautious about jumping to the worst case scenario just because there’s uncertainty and volatility. Tom started with this. What’s the most unusual circumstance we’re in right now? It’s that we have a lot of volatility and much more uncertainty than we had through the whole 40-year period of what’s called the Great Moderation. So things were pretty much placid and now suddenly things are highly volatile. People think that is precarious, certainly feels precarious sometimes. Then you’re looking for the worst way it can end. But the surprising thing has been the resilience.

President Barkin: I keep saying if you’re going to predict a recession, you’re going to be right eventually. But I’m not sure that means you’re a good forecaster. It just means you’re a stubborn forecaster. In our working lifetimes, the recessions have not come out of a gradual economy drifting down into recession. They’ve come out of sudden issues like the pandemic, like Lehman Brothers, like 9/11, like the Iraq war. So I just make that point, which is all of the forecasting that suggests we’re just going to drift into recession, that would be different from the way it’s worked over the last 40 or 50 years.

2026 Outlook

Kyla: It’s the very beginning of 2026. It’s a brand new year, a fresh start in a lot of ways. What is the one thing that you’re thinking about as you go into this year?

President Daly: We’ve come out of this period where we had high inflation, really high inflation, and a just good labor market and solid GDP growth and now we’re in a period where it looks like GDP growth is okay and the labor market has softened. So we had a policy move to try to offset that. We have inflation still printing above target and it’s going to be tempting for everybody to just look at what the next data point says, but we really need to back up and, and think about what are the longer-term drivers of the economy?

How are things shaping up over the next couple of years? We’re in the fine-tuning component of policy, we’re a stone’s throw from the neutral rate for some forecasters, we’re by the neutral rate of interest, for others, we have a little bit more room. We’re not in a place where we’re making large policy moves. We’re in a place where we’re fine tuning as the economy evolves. Having that, I’m really trying to be thoughtful about the discipline it takes to be in a period where you’re not trying to fight a big war, you’re trying to manage the small movements and think about the longer-term settling places for the economy and for interest rates and, and while we’re all trying to get price stability and preserve the soundness of the labor market.

President Barkin: If I have one thing, it’d be, we’re in this low hire, low fire environment. It’s not normal, but it’s not terrible. It’s just a different kind of environment. But it doesn’t feel like one that’s going to persist. So is it going to break more toward hiring or break more toward firing?

The break more toward firing is a situation we can all envision. Companies start announcing layoffs and all of the sudden the downsizing leads to all kinds of pullback. But I’m also looking for a break toward the hiring piece of it. There are two things worth considering:

If demand stays as strong as it is, eventually people are going to need to hire folks to fulfill that demand. If everyone starts going to restaurants and someone’s going to have to serve the meals and I’m looking for that break.

We talked a lot about AI. But I keep asking myself, if you really think AI is going to be fundamental, who are you going to hire? Me or somebody who’s technologically literate enough to actually deliver greater results with AI? I think that’s going to be good for the young people who today are not getting jobs because people are having temporary hiring for reasons. So I’m looking for that break too, where people say I’m going to really invest in AI and to do that, I’ve got to hire the AI literate at some scale.

So we’ll see. But I’m really watching the hiring and the layoff market very closely.

Kyla’s Thoughts

I think President Barkin’s point about the persistence of uncertainty really matters as we look into 2026, and the way to navigate it best is through diversification across the board. President Daly’s 1970s vs 1990s framing is really useful. It gives two concrete historical precedents with very different outcomes, and the key differences between the two was technology and policy response. So now, the key variable is if AI delivers real productivity gains which is something nobody can know yet. What’s interesting too is how much they’re complementing traditional data with direct observation. Sometimes talking to people about what they’re actually doing tells you more than waiting for the lagging data to confirm it, and it can help make sense of inflation expectations, which is the key warning signal for President Daly.

The extraordinarily persistent sentiment-spending disconnect is genuinely puzzling, and I do think people are frustrated by high price levels. Yet they’re still spending because employment is solid and wages have kept up. President Barkin’s point about wealthy consumers being supported by asset gains while lower-income consumers are making deliberate trade downs also helps explain why aggregate spending looks okay even when sentiment is terrible.

There were a lot of breaking points too in the conversation - the delicate balance of a low-fire, low-hire environment, the delicate balance of a lower-income consumer trading down, the delicate balance of a healthcare-driven labor market and an AI-driven economy. And President Barkin flags a particularly concerning concentration risk: both the investment boom (AI, data centers) and consumer spending (wealthy people with stock portfolios) are narrow and interconnected. If AI enthusiasm wanes, you could lose both engines at once. But again, all the predicted breaking points - excess savings running out, overheating, labor market collapse - haven't materialized. The economy keeps completely not breaking when people expect it to.

The communication challenges are real. President Daly’s shows the Fed is actively thinking about how their language gets interpreted and creates feedback loops in this extremely fast attention economy. And President Barkin’s point about recessions coming from sudden shocks rather than gradual drift is important. The current slowing doesn’t automatically lead to recession. There are actual tailwinds: monetary stimulus from rate cuts, fiscal stimulus from tax refunds, lower gas prices, which I wish we had more time to talk about. And it’s probably a good rule of thumb to embrace some positivity, amid all the negativity, even if it’s just counting some cranes!

This is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading.