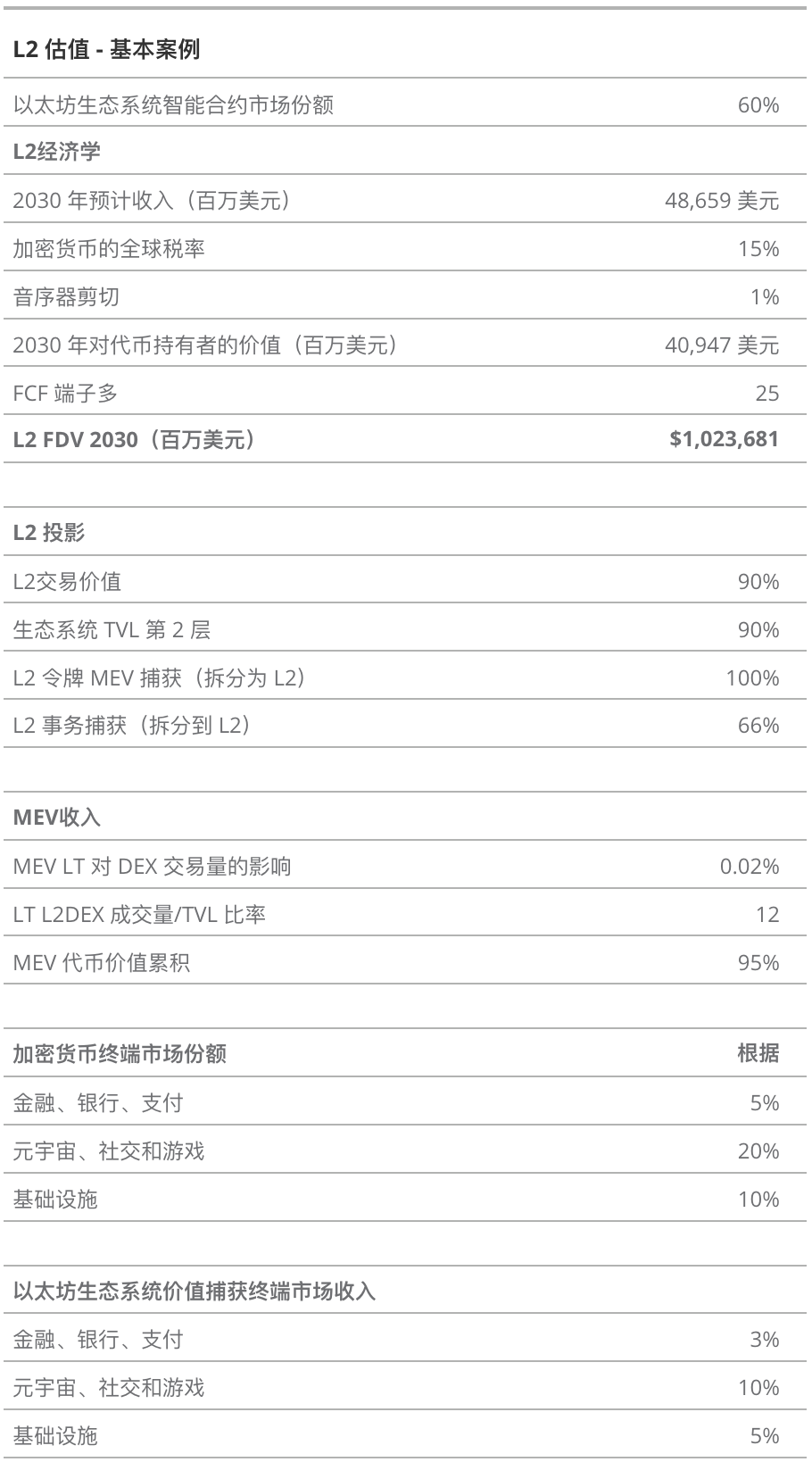

We evaluate 5 key areas of Ethereum Layer-2 and detail our base case valuation forecast of $1T for ETH L2 in 2030.

Please note that VanEck may have positions in the digital assets described below.

In this article we:

- Our conclusion is that the Ethereum Layer 2 landscape is currently overcrowded and has few winner-take-all characteristics.

- Evaluate layer 2 blockchains through the lens of developer experience, user experience, and technical capabilities.

- Showing the assumptions behind a base case valuation of Ethereum Layer-2 reaching $1 trillion in market capitalization by 2030.

- Overview of Layer 2 Blockchain

- The Role of Layer-2 in Scaling the Ethereum Network

- Layer 2 Types: Optimistic and Zero-Knowledge Rollups

- Tier 2 Revenue Model

- Layer-2 on-chain cost structure

- Layer-2 off-chain cost structure

- EIP-4844 Solution to L2 Data Costs

- Evaluate Tier 2 across 5 key areas

- Ethereum Layer-2 Valuation Prediction in 2030

Overview of Layer 2 Blockchain

Ethereum's dominance in the smart contract space faces a key obstacle: scalability. While the network offers unparalleled security and decentralization, transaction fees and processing times can soar as usage increases. To overcome this problem, Layer 2 solutions have emerged, and advancements such as the recent fork EIP-4844 are expected to unlock greater scalability for these Ethereum forks. Here, we analyze a range of Layer 2 solutions from the perspective of transaction pricing, developer experience, user experience, trust assumptions, and ecosystem size.

Layer 2 (L2) blockchains are connected networks that run on top of a main blockchain, such as Ethereum, to increase its ability to process transactions. By processing transactions on the main blockchain and then settling them back onto the main blockchain, L2 solutions help expand the functionality of a blockchain without compromising its security or decentralization.

It is well known that Ethereum’s current capacity is insufficient to carry all of the world’s financial transactions. More precisely, the world’s financial system needs to handle more than Ethereum’s long-term limit of about 19.2 USDC or 6.8 Uniswap transactions per second. However, this is a design limitation, as Ethereum’s administrators believe that censorship resistance is best achieved by allowing anyone to run an Ethereum node at low cost.

The result is that Ethereum has limited the capacity of its chain to reduce the network requirements, data storage requirements, and computer hardware requirements of its nodes. This effectively limits the number of bytes of data that Ethereum can process in a given time. Since transactions on a blockchain are nothing more than pieces of data that the blockchain deems to be correct, the capacity of a blockchain can be measured simply by how much useful data it can process.

Source: VanEck Research as of March 15, 2024.

To address these limitations, Ethereum’s developers initially proposed a “sharding” solution, which involved splitting the blockchain into 64 smaller, interconnected child blockchains, called “shards.” Each shard would process transactions in its own containerized child blockchain and then submit proof of activity for coordination by Ethereum’s parent blockchain. While this approach looked promising, and some components of it debuted on Polkadot starting in 2020, Ethereum developers ultimately abandoned the sharding plan, called Ethereum 2.0. This was because they believed it was not technically feasible and would not scale to Ethereum’s vision of becoming a blockchain for billions of users.

Instead, Ethereum’s roadmap shifts toward utilizing Layer 2 (L2) blockchains. These L2 networks process the majority of transactions outside of the main Ethereum blockchain, settling only the highest value transactions directly on them. This approach reduces the load on the main blockchain, allowing it to process more transactions efficiently. In this dynamic, Ethereum accrues value because the costs of these settlements must be paid in ETH; this strategy also reinforces the value of ETH as the real “oil” that powers the entire interconnected chain ecosystem.

Essentially, Ethereum’s main challenge is its limited ability to process, store, and compute data in the form of financial transactions. This bottleneck in data throughput can be addressed by offloading much of the data processing and computation to layer 2 blockchains. As a result, Ethereum’s development is now focused on enhancing its ability to integrate compressed transaction data from these L2 blockchains. But how exactly do these interconnected blockchains work, and what are their business models?

Ethereum ecosystem transactions and Ethereum mainnet market share

The Role of Layer-2 in Scaling the Ethereum Network

Layer 2 (L2) blockchains enhance Ethereum’s capabilities by aggregating multiple transactions into compressed packages called “rollups.” These “transaction bundles” are published to Ethereum by L2 at different intervals that are designed to balance transaction demand, security, and cost. As a result, Ethereum is becoming a “blockchain of blockchains.”

Each L2 is typically made up of its own series of smart contracts on Ethereum that track L2 transaction history, facilitate data transfers between L2 and Ethereum, run proof-of-fault or zk validator contracts (more on this below), and act as an asset custodian between Ethereum and L2. Very powerful computers called “sequencers” ingest and sequence all transactions that occur on the L2 blockchain. This is more powerful and cheaper than Ethereum because L2 runs a single very powerful server computer that simply receives transactions and sequences them. This dynamic allows L2 to handle a much greater data throughput than Ethereum. In contrast, Ethereum transaction processing involves hundreds of thousands of globally distributed validator nodes sending, interpreting, and agreeing on transaction data. This takes much more time due to the Ethereum consensus process and involves duplicating the work of one computer on each of the hundreds or thousands of Ethereum nodes. Logically, a single computer like a sequencer that processes transactions is much cheaper and faster than a globally dispersed, less capable system of computers that collectively use gigabits of internet bandwidth to send messages and hundreds of thousands of CPUs to process blockchain transactions.

Types of Layer-2: Optimistic Rollup (ORU) and Zero-Knowledge Rollup (ZKU)

There are two main types of L2s connected to Ethereum: Optimistic Rollups (ORU) and Zero-Knowledge Rollups (ZKU) . Both settle their ledger balances or “states” on Ethereum by sending a compressed version called a “Merkle Root . ” ORUs also publish a batch of compressed transaction data to make it easier to verify and track changes to the ledger over time.

Settlements in a layer 2 blockchain (L2) can be likened to updating a scoreboard for a baseball game inning by inning, with transaction data serving as detailed game data. For optimistic rollups (ORUs), they operate on the optimistic principle, meaning they are assumed to be accurate unless proven otherwise. If an entity (such as a high-frequency trading firm or a mathematically skilled researcher) identifies an incorrect or flawed Merkle root, they can submit a fraud proof (called a fault proof) to Ethereum. Entities monitoring ORUs for fraud have a 7-day window (called a "challenge period") to detect any fraudulent activity after the state is updated. Once that period is over, transactions within the ORU are considered final. If a fault proof successfully proves fraud, the smart contract that oversees the state of the ORU reverts all transactions to the state before the fraud began. The challenge period extends for 7 days, after which each batch of transactions is irrevocably finalized.

At the time of writing, only 4 chains have live fraud proofs out of the 46 L2s we track via l2beat . Two of these four fall under the umbrella of Arbitrum, which has the highest Total Value Locked (TVL) of all L2s at $4.31B and only allows fraud proofs from a whitelisted set of entities.

The most popular ORUs are Arbitrum, Blast, Optimism, Manta, Metis, Mantle, and Base.

Total Value Locked (TVL) and Optimistic Revenue Units (ORU)

Source: Defillama, TokenTerminal, as of March 12, 2024. No recommendation to buy or sell any of the names mentioned in this article. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Zero-knowledge rollup (ZKU) operates similarly to ORU, but with one key difference. While ORU submits both the transaction data Merkle root and the state Merkle root to Ethereum, ZKU only sends a zero-knowledge proof of the transaction data. This is because ZKU does not operate under the assumption that the submitted state root is correct. Instead, once the proof is submitted to Ethereum, the smart contract verifies the authenticity of the ZKU transaction package.

Therefore, ZKU has no fault proofs, as proofs are generated for every state update. Unlike ORU, ZKU transaction data is considered final once a proof is accepted on Ethereum, ensuring immediate finality and eliminating the need for challenge periods.

The most important ZKUs at the moment are Starkware, zkSync, zkScroll, Linea, and *c zkEVM

The underlying economics of ZKU and ORU are very similar to L1 blockchains. Both types of rollups make money when users create activity on their chains and pay ETH fees to Ethereum. Currently, all L2s are priced in ETH for transactions, as this is the token required to settle transaction data to Ethereum.

Tier 2 Revenue Model

Regardless of the process, it is important to understand that transaction ordering has value, and blockchains can make money by selling the right to order transactions. This figure illustrates how three different transaction ordering models create different revenue streams.

Source: VanEck Research as of March 25, 2024. Explanation: Assume TX2 is a high-value transaction buying $1 million of tokens on L2. In FIFO, everyone pays the same amount to the sequencer. In priority ordering, TX2 pays first to the sequencer. TX3 and TX4 pay additional fees to get ahead and behind TX2 in the auction for a specific slot.

Layer 2 Transaction Ordering: Priority, FIFO, and Auctions

L2s charge users a fee for including transactions in each block. It is composed of a base fee and a priority fee. Some L2s charge a priority fee, such as Optimism . Priority fees enable users to be first in line at the top of transaction blocks. In the past 6 months, the top 10 L2s on Ethereum have earned $232 million in revenue from user transactions alone. This ability to "cut the cord" by paying a priority fee is beneficial to users who engage in time-sensitive activities such as arbitrage trading.

Arbitrum uses a first-in, first-out (FIFO) ordering method for transactions as they arrive. In some cases, users may prefer their transactions to follow specific other transactions on a block. A common strategy called "backward running" involves trading immediately after a significant transaction to exploit price differences between decentralized exchanges (DEXs) for arbitrage opportunities. More malicious trade ordering techniques, such as "sandwich attacks," involve strategically placing a buy order before a user's planned trade and a sell order immediately after it. This manipulation drives up the price of a desired token before a user's trade executes, forcing them to buy at an unfavorable, inflated price.

On Ethereum, order books are monetized through software added to Ethereum validator software. This software, called Flashbots, allows validators to auction the right to order transactions (and insert their own transactions) to external entities. This auction generates "maximum extractable value" (MEV), which increases the returns for validators and stakers. While L2s have the potential to monetize MEV by auctioning block ordering rights, no L2 has officially done so yet. However, trading firms may already be locating their servers close to L2 servers, similar to how stock and commodity exchanges do it.

Looking ahead, many L2s plan to decentralize their sequencer sets, which may involve staking tokens — perhaps ETH from the Eigenlayer DA or native tokens from each rollup. Decentralization of sequencers could unlock new revenue streams for MEV. For context, Ethereum’s average MEV take rate on DEX volume is around 4 basis points (bps), while other blockchains like Polygon and Solana have rates of 0.4bps and 3.5bps, respectively. These rates likely underestimate the full scope of MEV due to tracking challenges and incentives to conceal profits. By estimating MEV take rate based on DEX volume, if Arbitrum’s MEV is captured at a rate of 3.0 bps, the amount would come to $58.9 million — 57% of Arbitrum’s pure fee revenue.

Arbitrum Revenue Achieves 3 bps MEV on DEX Volume

Source: Artemis XYZ as of March 20, 2024. No recommendation to buy or sell any of the names mentioned in this article. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Layer-2 on-chain cost structure

Layer 2 (L2) incurs costs primarily through Ethereum Gas fees as they periodically publish transaction data, settlements, and proofs to Ethereum. But the cost structures of Zero-Knowledge Rollups (ZKU) and Optimistic Rollups (ORU) differ. While both update their state on L1, ORU has to pay heavy on-chain data costs, while ZKU has to spend money on proof generation and verification. Regardless, the consequence of relying on Ethereum is that L2’s input costs are subject to fluctuations in the Ethereum block space. Most of the time, this cost difference is passed on to users. However, the profits earned by L2 are therefore very volatile.

Prior to EIP-4844, L2 published settlement data and proofs to Ethereum as a single transaction, with a “message field” of each transaction structure called “call data.” This is a “hack” that exploits a component of Ethereum’s standard transaction format to hold compressed L2 data. While this is novel, it is very expensive. For example, in February, Optimism paid $5.7 million, Arbitrum paid $7.2 million, and Scroll paid $6.7 million to publish call data to Ethereum.

Source: VanEck Research, Celestia, as of March 14, 2024.

Compared to ORU, the cost component of ZKU is inherently higher because ZKU submits zero-knowledge proofs and call data to Ethereum. While ORU may also involve proof costs, these costs are typically outsourced to third parties who challenge the state when needed, so they do not significantly impact the base cost of ORU. The cost of verifying ZKU's zero-knowledge proofs on Ethereum can be extremely high. Despite Ethereum's optimization efforts, such as using native operating code to simplify zk-proof verification, fees are still high, for example, Scroll's ZKU incurred $1.1 million in proof fees in the first 13 days of March.

Due to the high cost of proof, ORU's average profit margin over the past six months was 26.7%, while ZKU's average profit margin was 21%. Logically, rollups can send more transactions in fewer batches to reduce variable batch posting fees. However, infrequent batch postings can also be caused by less transaction throughput occurring on L2. Regardless, the frequency with which L2 batches are posted to Ethereum is a profitability lever that L2 can pull, but at the expense of user experience. In practice, L2s decide to batch post based on a calculation based on the number of transactions they can fit into a block, the Ethereum L1 gas price, and the incoming transaction flow per L2.

Daily L2 batch settlement costs with Ethereum

Source: Dune @niftytable, Etherscan as of March 14, 2024. No recommendation to buy or sell any of the names mentioned in this article. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Technically, in addition to simple “scoreboard” solutions, L2s can also publish a broader understanding of what is happening on the L2. Price competition between L2s to provide users with the cheapest transactions results in L2s often choosing the most economical data to publish. Typically, this means publishing only “state differences” for ZKUs, and for ORUs it means publishing highly compressed transaction data. Curiously, while ZKUs are not technically required to publish full transaction data, some ZKUs still do so. Starknet and zkSync only publish “state differences”, while Linea, Polygon, and Scroll publish full transaction data. This is done because it can be challenging for things like browsers and wallets to follow the blockchain without transaction data. Another possibility is that publishing full transaction data can increase transparency so that anyone can run a node to follow ZKU. ZKUs may also be willing to open up provers to anyone in the future, and publishing full transaction data to Ethereum allows ZKU to “decentralize” its blockchain at the “prover” point.

Many L2s currently reduce costs by improving compression efficiency. For example, on February 13, Linea deployed a new compression scheme that increased the compression rate on the chain by 10 times, from about 500 bytes per transaction to about 50 bytes. By 2024, the average transaction size of other L2s (ORU and ZKU) on Ethereum was 300 bytes. While compressed transactions may save L2 data costs, it reduces its potential due to the time required to compress transactions.

L2 On-chain Monthly Margin

Source: Dune @niftytable, Artemis XYZ as of March 13, 2024. No recommendation to buy or sell any of the names mentioned in this article. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

EIP-4844 Solution to L2 Data Costs: Blob Spaces

On March 13, 2024, Ethereum passed the Dencun upgrade, which included several important changes, the most important of which was the creation of the so-called "Blob Space". Prior to this upgrade, the main challenge facing Layer-2 was the high cost associated with publishing transaction data to Ethereum. Recognizing this, Ethereum's solution was to strategically create a specialized data layer, commonly known as Blob Space, designed specifically for L2 data publishing.

This newly established layer provides a targeted transaction environment tailored specifically for receiving data from the L2 network. The innovation of Blob Space lies in its transient data handling - data blobs published here are only retained for four weeks before being deleted, significantly reducing Ethereum's data overhead. As a result, L2 can choose to bypass the main Ethereum layer and publish directly to Blob Space.

Ethereum's Blob Space layer has its own gas prices and follows the same set of rules as Ethereum's regular execution layer. The result is that transactions that publish data from L2 no longer have to compete with regular Ethereum transactions for block space. The design of the dedicated transaction layer also makes data much cheaper than publishing it to Ethereum as call data. At the time of writing, Data Blob has reduced L2's gas usage fees (-96%).

Ethereum (ETH) L2 Data Publishing Costs

Source: Dune @niftytable, Artemis XYZ as of March 19, 2024. No recommendation to buy or sell any of the names mentioned in this article. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Layer-2 off-chain cost structure

The first part of the off-chain cost expenditure for Layer 2 (L2) is the sequencer they use to sequence transactions. This is basically just a high-end server located in a data center. For most L2s, the infrastructure or business entity behind the L2 pays the cost of the sequencer. In the grand scheme of things, the cost of running the sequencer itself is small, about $1000-2000 for the equipment and maybe another $3000-5000 per month in manpower. This cost is consistent for both optimistic rollups (ORU) and zero-knowledge rollups (ZKU).

A less discussed but important cost element of ZKU involves the operation of the prover. Unlike the sequencer, which generates the state root, the prover is responsible for creating zk proofs that are verified on the Ethereum network. This computation process typically occurs on cloud computing platforms such as AWS.

According to decentralized zk prover project Gevulot , the cost of proving will be between “10-20% of Ethereum verification costs.” Furthermore, these costs scale with the volume of transactions generated by each L2. ZKU faces a balance between cost and user experience and may choose to reduce the frequency of proofs posted to Ethereum as a potential cost-saving measure. Through a process called recursion, ZKU provers can merge multiple proofs into a single submission, which while increasing off-chain computational requirements can optimize economics by reducing expensive proof verification on Ethereum.

At the time of writing, all ZKUs run their own attesters and pay for attestation generation directly. However, over time, many intend to decentralize attestation generation.

Evaluate Tier 2 across 5 key areas

In our analysis of the critical Tier 2, we use five main variables to measure potential success or failure:

- Transaction Pricing — User’s Transaction Costs

- Developer Experience – Build products and applications with ease

- User experience – simplicity of deposits, withdrawals and transactions

- Trust Assumptions - Liveness and Safety Assumptions

- Ecosystem size — how many interesting things can be done

1. Layer-2s transaction pricing

The source of the transaction pricing differences comes from a combination of data compression, data posting efficiency, L2 scale, proof costs (for ZKU), and most interestingly, the profit share of each L2. L2s can also schedule posts to Ethereum based on Gas prices, but in practice, we have not found empirical evidence to support this possibility. This may be due to the general difficulty of predicting future Ethereum gas prices.

The main difference in pricing economics between ZKU and ORU is that ZKU has higher fixed costs than ORU. This is because ZKU must pay for proof generation on Ethereum and proof verification on Ethereum. Proof generation/verification is a large static cost that does not increase significantly as each proof covers more transactions. In contrast, ORU must post the full transaction data to Ethereum. Although ORU uses different compression mechanisms to reduce data costs, the cost of posting to Ethereum is very expensive. Since more transactions on ORU means more data needs to be submitted to Ethereum, the cost of posting to Ethereum increases. However, with EIP-4844, the cost of posting data to Ethereum has been significantly reduced, and these savings result in cheaper transaction pricing for ORU. Similarly, ORU can also choose to place transaction data on cheaper data availability blockchains such as Celestia, EigenDA, and Avail. Currently, Manta Pacific and Aevo post transaction data to Celestia.

The cheapest chains for average transaction costs in 2024 are Mantle ($0.17), zkSync ($0.21), and Starknet ($0.25). Each chain is able to stand out in terms of pricing using different techniques. Mantle, an ORU, is able to keep transactions cheap because it accepts lower-than-average margins (19.9%), uses its own data availability (Mantle DA) for full transaction batch publishing, and updates its state root to Ethereum the second least frequently, every 20.7 minutes. zkSync, a ZKU, is able to price transactions cheaply due to its high transaction volume (94.9 million), the highest of all L2s, which makes its proof system very economical. Meanwhile, ZKU chain Starknet settles to Ethereum the least frequently among the top 10 L2s, every 57.8 minutes, while also only publishing state differences instead of full transaction data. These two cost savings result in the least amount of data being settled to Ethereum per transaction. Curiously, we estimate that Starknet lost $0.09 per trade as of March 13, 2024.

Competitive differentiation at L2

2024 data. Source: Dune @niftytable, Artemis XYZ as of March 13, 2024. No recommendation to buy or sell any of the names mentioned in this article. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

2. Layer-2s Developer Experience

Developer experience is another important point of competitive advantage for Layer-2. The fundamental understanding of making the developer experience the simplest is to achieve EVM compatibility. This means that smart contract code, tools, and developer libraries can be directly ported from Ethereum to L2 for use. Since Ethereum has a large network of developers, this is believed to give each L2 an advantage. Currently, the vast majority of L2s are compatible with EVM. However, due to the limitations of zero-knowledge proofs, ZKUs often have subtle differences that developers must comply with.

Some developers also believe that adhering to EVM compatibility is a drawback, as the EVM places significant limitations on blockchain functionality while excluding developers who are more familiar with other computer languages. For example, Starknet smart contracts are written in a language called Cairo, which is more efficient for Starknet's zero-knowledge extensions. Of course, this is a trade-off, and anyone deploying to Starknet must understand the intricacies of Cairo. Movement Labs is another L2 developer that allows smart contracts to be written in the Move language, which attracts developers who want to learn Move. For those who are more familiar with Solana's programming language Rust, Eclipse is building a layer 2 blockchain that runs in the Solana virtual machine. This even extends to other languages, such as Web Assembly, as Fluent has created a general-purpose L2 that supports WASM.

3. Second-layer user experience

User experience is another pillar of Layer-2 competition. The most basic component of this is loading and removing assets from L2. In most cases, onboarding between L2s does not differ significantly, but some centralized exchanges (CEXs) allow native assets to be moved to each L2. For example, Kraken allows users to withdraw USDC to Arbitrum and Optimism, while Coinbase allows USDC to be ported to Optimism and Base.

Finality (the point at which a transaction on L2 becomes irreversible) marks a significant difference in the user experience between optimistic rollups (ORU) and zero-knowledge rollups (ZKU). For ORU, finality occurs after the fraud challenge period ends, while for ZKU, finality occurs after the state root and its proof are published to Ethereum. One of the consequences of the difference in finality is exiting L2. For ORU, users must wait 7 days before they can transfer their funds back to Ethereum. For ZKU, the same process may take as little as an hour, depending on how frequently ZKU publishes settlements and proofs, as well as the security systems of each chain. While zkSync publishes proofs every 6 minutes and updates the state every hour, due to zkSync's security module, users must have a 24-hour waiting period before they can bridge their assets to Ethereum.

Current throughput and latency

Source: VanEck Research as of March 19, 2024. No recommendation to buy or sell any of the names mentioned in this article. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Familiar tools and interfaces are critical when users interact with L2. Adopting familiar wallets and blockchain browsers from Ethereum to L2 greatly improves user comfort. This seamlessness is critical because most L2s adopt a similar experience to Ethereum, ensuring that the learning curve for people migrating across platforms is minimal. In the field of quantifiable user experience metrics, latency and throughput stand out. Latency refers to the time it takes for a transaction to be confirmed by the network after submission, while throughput measures the network's ability to process transactions per second.

The slowest block time or round-trip time (RTT) — the duration between a user’s transaction reaching the sequencer and receiving a confirmation back — generally defines L2 latency. Arbitrum, for example, has a very low latency potential of 0.25 seconds, though actual latency may vary based on geography and the user’s distance from the sequencer, which is presumably located in a Silicon Valley data center.

zkSync is known for having the highest theoretical throughput, being able to process up to 434 swap transactions per second. However, both latency and throughput are tunable parameters in L2 networks.

ZKU is currently bottlenecked by how fast its prover can process incoming transactions, while ORU is limited by the efficiency of transaction data compression and the rate at which Ethereum can absorb that data. Currently, L2 voluntarily limits its throughput to align with Ethereum’s capacity. If L2 were to fully utilize Ethereum’s block space (given Ethereum’s current data cap of about 937.5kb per block, plus an additional 375kb from three data blobs), it could theoretically scale to about 1.3 MB per block, or 110kb per second.

For a specific L2 like zkSync, with an average of 62 bytes per transaction, fully utilizing Ethereum block space could potentially surge to 1,764 transactions per second. In contrast, an ORU like Arbitrum, with an average of 255 bytes per transaction, could achieve a processing rate of 429 transactions per second under the same conditions.

Throughput could be further increased by integrating a data availability blockchain such as Celestia. However, this approach raises concerns about compromising user security, as alternative blockchains may not offer the same level of security guarantees as Ethereum. The choice to scale throughput in this way is a delicate one that requires balancing improved performance with the inherent security provided by Ethereum’s robustness.

4. Layer 2 Trust Assumptions

Source: VanEck Research, l2beat as of March 19, 2024. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

There is a big difference in the security and liveness guarantees that L2s provide to users. Security refers to the properties of a blockchain that ensure that only the account owner can access his/her assets, while liveness refers to the safeguards that ensure that assets can be exploited. Since L2s rely on a single sequencer that both orders blocks and “proposes” them to L1 (Ethereum) for settlement, sequencer failures are of the greatest concern to L2 users. This is because each L2 currently runs a single sequencer, and if it fails, that L2 cannot process transactions. While assets cannot be stolen in the event of an outage, users will also not be able to access them until the outage is resolved. At the same time, if a malicious entity is able to take over a sequencer, they have the potential to create fraudulent transactions to take assets off the L2. The weakness of all current L2s is that they each only run a single sequencer, and that sequencer is usually centrally operated by the foundation behind the L2.

L2 manufacturers are aware of the issues presented by sequencer failure or takeover, and some have implemented novel safety valves. These vary by L2 and its security. Complicating matters is that some of these safeguards open up possibilities for other areas of attack. Some of the guardrails created to protect users include allowing users to delete assets under certain conditions, submit L2 blockchain transactions using an L1 host, and even propose L2 blocks. Most of the time, these situations arise when there is an apparent failure somewhere in the L2 system.

Some L2s are developing frameworks where anyone can become a sequencer, and allow multiple sequencers to take turns sequencing. This will come with people running sequencers establishing economic bonds (most likely in each L2 native token) to penalize cheaters. Companies like Espresso , Astria , and Fairblock are examples of projects building software for decentralized sequencers. Currently, L2 Metis is the furthest along in pioneering decentralized sequencers on L2. The Metis community recently passed a governance vote that created a framework for decentralized sequencers and allowing multiple sequencers to exist.

The next point in the trust assumption change we discussed above is called “data availability”. ZKU provides proof that a state update is correct, while ORU provides proof that allows anyone to prove that a state update is incorrect. However, in both cases, it is important to know the source of the data in order to generate a proof for a ZKU or ORU. Ideally, this data is easily “available” on L1 (Ethereum) so that anyone can verify the underlying data from which the proof was generated. Blockchains such as Immutable X and Metis keep full transaction data elsewhere. While ZKU does not require publishing full transaction data, chains like Linea and Polygon zkEVM do, while Starknet and zkSync only publish state differences. Additionally, L2 publishes data to Ethereum, while other L2s publish it to dedicated data availability blockchains such as Celestia. Publishing data on other chains arguably makes L2s less secure than Ethereum because it introduces new trust assumptions.

Another interesting dynamic with ORUs is that, as it stands, almost none of them are fraud-proof. This means that anyone using them is subject to censorship by the sorter (transactions not finalized). Arbitrum is an exception, which allows fraud proofs. But even in Arbitrum’s case, only whitelisted entities can submit fraud proofs. ZKU, on the other hand, relies on provers (different entities than sorters) to issue proofs. If a ZKU prover fails, some chains allow users to submit their own proofs (just do zero-knowledge math!) in order to get the transaction included in L2.

Regardless, layer 2s have many issues with trust assumptions. However, they currently have hundreds of thousands of daily active users, so it seems no one will care until something major goes wrong. To simplify our view of the range of safeguards in place at L2s, we ranked them from most risky to least risky and found Arbitrum to be the current (although still insufficient) gold standard.

5. Layer-2s Ecosystem Scale

L2 Bridge TVL

Source: Dune @21co As of March 19, 2024. No recommendation to buy or sell any of the names mentioned in this article. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The most important competitive factor for L2s is the ecosystem each L2 creates. Blockchains are marketplaces for services and digital goods. The more useful things are done on a blockchain, the more value it generates through user transactions, demand for its native token, and network effects. Unfortunately, metrics that measure blockchain activity don’t always translate correctly into the value of that blockchain’s ecosystem. Applying Goodhart’s Law states that once a metric becomes significant in crypto, it’s more likely that those metrics will be manipulated. This rule becomes even more ironclad when we consider airdrop farmers (see the third paragraph of our January Monthly for an explanation), who are performing meaningless activities to receive free airdrops of token value.

Generally speaking, it is users who are willing to bring value to the blockchain and engage in meaningful activities to generate fees that matter. In this regard, Arbitrum, Optimism, and Blast have shown that they have ecosystems that matter to users, as these have bridged $16.3B, $7.85B, and $2.43B to each, respectively. In most cases, Layer-2s generate user interest and activity through airdrops of their native tokens. For example, Optimism has given away nearly 25% of its current floating supply to users in the form of active airdrops. Arbitrum has given away over $1.84B in tokens to individuals who use Arbitrum. Blast has taken this concept a step further to attract bridged value, with the premise that Blast itself and teams building on Blast may airdrop tokens. Conceptually, Layer-2s compete by giving away free tokens that grow in value as each L2 network grows.

Fully Diluted Value (FDV)/Revenue and Market Capitalization (MC)/Revenue

Source: Artemis XYZ as of March 21, 2024. No recommendation to buy or sell any of the names mentioned in this article. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

By measuring trailing 12 month (TTM) revenues as multiples to fully diluted valuation (FDV), each L2 has a multiple that far exceeds Ethereum. However, this dynamic changes if we change the multiples to be based on floating token supply rather than fully diluted value. This is a strange disconnect that has to do with the issuance schedule of L2 tokens - most L2 projects have only released a small fraction of their supply. In reality, we see L2s trading more based on speculation about long-term value accumulation rather than current revenue dynamics. We attribute this dynamic to the potential for L2s to have much higher future revenue than Ethereum.

We expect L2 revenue to surpass Ethereum as Ethereum cannot match L2’s transaction throughput or user experience. We are also increasingly seeing cases where the general purpose roller shutter market is consolidated by a few major players. This is due to the network effects of on-chain application composability and shared value. It is also attributed to rollup frameworks such as OP Stack or Arbitrum Orbit becoming dominant and OP/ARB tokens accruing value from other L2s and even Layer-3 (blockchains that submit state to L2). It is also clear that most rollups will eventually move to zero-knowledge frameworks (ZKU) due to their many advantages.

In the long term, we still think Ethereum blockspace will be expensive, and the result may be that many L2s merge proofs into a unified proof layer that "recursively" combines all the proofs of its layer components. This is especially true in the case of application and sector-specific aggregations. An example of a concept is the aggregation of polygons. Conceptually, something like an "aggregation layer" could also greatly improve the user experience, as it would be more economical to frequently publish proofs and state roots to allow crossing L2 and Ethereum bridges in seconds rather than hours.

As such, we see a brutal competition among L2s where network effects are the only moat. As such, we are generally bearish on the long-term value prospects of most L2 tokens. The top 7 tokens in L2 already have a combined FDV of $40B, and there are many strong projects aiming to launch in the medium term. This means that over the next 12-18 months, FDV in L2 tokens could increase by $100B. It seems like a bridge too far for the crypto market to absorb even the limited supply without a deep discount. Furthermore, while there is reason to believe that some L2 tokens will become valuable, the path to value accrual is less predictable than in other areas of crypto. This is especially the case since L2 tokens are not even the base currency in their own ecosystem.

In addition to the dominance of a few rollups in general-purpose L2s, we predict the emergence of thousands of use-case-specific rollups in the future. These L2s will be segmented by sector, application, or function. An enterprise might build a rollup explicitly as its own revenue and/or cost center, such as building an asset management layer 2 chain. Other types of chains might be specialized for hosting entire sectors, such as a rollup that hosts a social media network and applications that want to build products and services for that social media network.

Ethereum Layer-2 Valuation Prediction in 2030

We found a 2030 valuation for the L2 space by applying an FCF terminal multiple to our expectations of future cash flows. We estimate the revenue that will supply these cash flows by:

- Transaction income (including transactions on the blockchain)

- Estimating the revenue TAM of end markets that could leverage public blockchains

- Calculate the number of TAMs actually using the public chain

- Forecasting the market share of public blockchains in the Ethereum ecosystem

- Apply a fee to end-market revenues that utilize the Ethereum ecosystem for settlement and transactions

- Splitting transaction value between Ethereum and L2

- MEV (transaction ordering on the blockchain)

- Estimating the value of assets (including currencies, securities, and digital assets) that will be secured by the Ethereum ecosystem

- Predicting DEX volume in the Ethereum ecosystem by applying asset turnover estimates to our forecasts of the value of assets in custody in the Ethereum ecosystem

- Multiplying DEX transaction volume by MEV utilization rate gives the total MEV value

- Distributing value between Ethereum and its L2

Source: VanEck Research as of March 21, 2024. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The information, valuation scenarios and price targets in this blog are not intended as financial advice or any call to action, recommendation to buy or sell, or as a prediction of Layer-2's future performance. The actual future performance of Layer-2 is unknown and may differ materially from the hypothetical results described herein. There may be risks or other factors not considered in the scenarios presented that could hinder performance. These are merely simulated results based on our research and are provided for illustrative purposes only. Please conduct your own research and draw your own conclusions.

Links to third-party websites are provided for convenience only, and the inclusion of such links does not imply any endorsement, approval, investigation, verification or monitoring by us of any content or information contained in or accessible from the linked website. By clicking on a link to a non-VanEck web page, you acknowledge that the third-party website you are entering is subject to its terms and conditions. VanEck is not responsible for the content, legality of access or suitability of third-party websites.

For more digital asset insights, sign up in our subscription center .

Disclosure

Coin Definition

- Ethereum (ETH) is a decentralized open-source blockchain with smart contract capabilities. Ether is the platform's native cryptocurrency. Among cryptocurrencies, Ethereum's market capitalization is second only to Bitcoin.

- Arbitrum (ARB) is a Rollup chain designed to improve Ethereum's scalability. It does this by bundling multiple transactions into a single transaction, thereby reducing the load on the Ethereum network.

- Optimism (OP) is a second-layer blockchain on top of Ethereum. Optimism benefits from the security of the Ethereum mainnet and helps scale the Ethereum ecosystem by using optimistic rollups.

- Polygon (MATIC) is the first well-structured, easy-to-use Ethereum expansion and infrastructure development platform. Its core component is the Polygon SDK, a modular and flexible framework that supports building many types of applications.

- Blur (BLUR) is the native governance token of Blur, a unique non-fungible token (NFT) marketplace and aggregation platform that provides advanced features such as real-time price feeds, portfolio management, and multi-market NFT comparison.

- Solana (SOL) is a public blockchain platform. It is open source and decentralized, using Proof of Stake and Proof of History to achieve consensus. Its internal cryptocurrency is SOL.

- Polkadot (DOT) is a sharded heterogeneous multi-chain architecture that enables external networks as well as custom first-layer “parachains” to communicate, creating an interconnected internet of blockchains.

- Linea is a network that extends the Ethereum experience and works out of the box with the Ethereum Virtual Machine to deploy existing applications.

- Blast (BLAST) is an EVM-equivalent Ethereum optimistic rollup with native yield functionality designed to increase revenue and maintain value for network users.

- Manta is an EVM-equivalent Ethereum optimistic rollup with a native yield function that provides a “passive income” stream for savers.

- Metis is an Ethereum token that serves as the internal currency for staking and payments in the Metis crypto ecosystem.

- Mantle Network is an Optimistic rollup (ORU) that scales Ethereum and is designed to be compatible with the EVM.

- Base is an Ethereum layer 2 incubated by Coinbase and built on the open source OP Stack, allowing developers to easily deploy reliable and secure applications on a scaling solution with low transaction fees.

- Scroll is a security-focused scaling solution for Ethereum that leverages innovations in scaling design and zero-knowledge proofs to build a new layer on top of Ethereum.

- Starknet is an Ethereum Layer 2 scaling solution that uses zero-knowledge rollups based on trustless “STARK” proofs from StarkWare Industry.

- zkSync Era is a layer 2 rollup that uses zero-knowledge proofs to scale Ethereum without compromising security or decentralization.

- Zora is a universal media registry protocol. It’s a way for creators to publish creative media, earn money from their work, and have others build on and share the content they create.

- Celestia is a blockchain network that introduces a modular approach to blockchain design and functionality.

- EigenDa is a secure and decentralized data availability layer that enables Ethereum developers to achieve unprecedented high transaction speeds and low transaction costs on Ethereum.

- Avail is a modular blockchain specifically designed to meet the needs of next-generation trust-minimized applications and sovereign rollups.

- Aevo is a decentralized derivatives trading platform focused on cryptocurrency options and perpetual futures trading.

- Rust is a multi-paradigm programming language that publishes and maintains independently released packages that contain features for many different types of cryptographic algorithms.

- Eclipse is a platform for deploying modular blockchains. Eclipse provides a flexible modular architecture that allows developers to choose the virtual machine, settlement process, consensus, and data availability layer that best suits their needs.

- Kraken is a San Francisco-based cryptocurrency exchange where market participants can trade a variety of cryptocurrencies.