Compiled by: Liu Jiaolian

Although it is already 2024, and BTC ETFs have landed in the US stock market and our Hong Kong stock market, there are still some people who are late to the party and have insufficient knowledge, and they talk about the fallacy that Bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme. Therefore, Jiaolian compiled the long article "Why Bitcoin is not a Ponzi scheme: a point-by-point analysis" written by American investor Lyn Alden on January 11, 2021 as follows, which complements the above article on June 8, 2021 on Jiaolian, hoping to help readers who are new to this industry to solve their doubts.

Text | Lyn Alden. Why Bitcoin is Not a Ponzi Scheme: Point by Point. 2021.1.11

One of the concerns I've seen about Bitcoin is that it's a Ponzi scheme. The argument goes that because the Bitcoin network is continually dependent on new buyers, eventually, as new buyers run out, the price of Bitcoin will collapse.

Therefore, this article takes a hard look at this concern by comparing Bitcoin to systems with Ponzi-like characteristics to see if this claim holds water.

In short, Bitcoin does not meet the definition of a Ponzi scheme, either narrowly or broadly.

Definition of a Ponzi Scheme

To begin the discussion on whether Bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme, we need a definition.

The following is the definition of a Ponzi scheme by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)[1]:

“ A Ponzi scheme is an investment scam that uses funds from new investors to pay out existing investors. Ponzi scheme organizers typically promise to invest your money in return for high returns with little to no risk. But in many Ponzi schemes, the scammers don’t invest the money. Instead, they use the money to pay out earlier investors and may keep some for themselves.

With little legitimate income, Ponzi schemes require a constant flow of new money to survive. These schemes collapse when it becomes difficult to recruit new investors or when a large number of existing investors cash out.

The Ponzi scheme is named after Charles Ponzi, who defrauded investors through a postage stamp speculation scheme in the 1920s.

They further list the “red lights” to watch out for:

“ Many Ponzi schemes share common traits. Look out for these warning signs:

High returns, low or no risk. Every investment carries some degree of risk, and higher-yielding investments are generally riskier. Be highly skeptical of any "guaranteed" investment opportunity.

Too stable returns. Investments tend to rise and fall over time. Be skeptical of investments that appear to regularly generate positive returns regardless of overall market conditions.

Unregistered investments. Ponzi schemes often involve investments that are not registered with the SEC or state regulators. Registration is important because it allows investors to learn about a company’s management, products, services, and financial information.

Unlicensed sellers. Federal and state securities laws require investment professionals and firms to be licensed or registered. Most Ponzi schemes involve unlicensed individuals or unregistered firms.

Secretive, complex strategies. If you don’t understand investing or don’t have access to complete investment information, avoid investing.

Paperwork issues. Errors in account statements can be a sign that funds are not being invested as promised.

Difficulty withdrawing funds. If you don’t receive payments or have difficulty withdrawing funds, be suspicious. Ponzi scheme promoters sometimes try to prevent participants from cashing out by offering higher returns to keep participants in the program.

I think this is a good set of information. We can see how many properties (if any) Bitcoin has. ---

[1] https://www.investor.gov/protect-your-investments/fraud/types-fraud/ponzi-scheme

The launch of Bitcoin

Before comparing Bitcoin point by point to the above list, we can first review how Bitcoin was launched.

In August 2008, a person who called himself Satoshi Nakamoto created Bitcoin.org.

Two months later, in October 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto released the Bitcoin white paper. This document explains how the Bitcoin technology works, including a solution to the double-spending problem. As you can see from the link, the white paper is written in the format and style of an academic research paper, as it proposes a major technical breakthrough that provides a solution to a well-known computer science problem related to digital scarcity. There are no promises of getting rich or rewards in the paper.

Three months later, in January 2009, Nakamoto released the original Bitcoin software. In the blockchain’s custom Genesis Block, he included a timestamped headline from a Times of London article about bank bailouts, likely to prove there was no pre-mine and to set the tone for the project.

From then on, he spent six days to complete the work, mined Block 1 containing the first 50 spendable bitcoins, and released the Bitcoin source code on January 9. On January 10, Hal Finney publicly stated on Twitter that he was also running the Bitcoin software, and from the beginning, Satoshi Nakamoto tested the system by sending bitcoins to Hal.

Interestingly, since Satoshi Nakamoto showed how to do this in his white paper more than two months before he himself launched the open-source Bitcoin software, it is technically possible that someone could have used the newfound knowledge to launch a version before him.

This seems unlikely, since Satoshi was the first mover and had a deep understanding and awareness of all this, but it is technically possible. He leaked key technical breakthroughs before launching the first version of the project. Between the publication of the white paper and the release of the software, he answered various questions. He explained his choice of white paper to several other cryptographers on the email list and responded to their criticisms, almost like an academic paper defense. If they were not so skeptical, several of these technicians might have "stole" the project from him.

After its launch, a set of equipment widely believed to belong to Satoshi Nakamoto was a large miner of Bitcoin for the first year. Mining is necessary to continuously verify transactions for the network, and Bitcoin was not quoted in US dollars at the time. Over time, he gradually reduced the amount of mining as mining became more decentralized across the network. Nearly 1 million Bitcoins are believed to belong to Satoshi Nakamoto, which he mined in the early days of Bitcoin and never moved from the initial address. He could have cashed out at any time and made billions of dollars in profits, but now, more than a decade after the birth of the Bitcoin project, he has not done so. We don't know if he is still alive, but most of his coins have not been moved, except for some early coins used to test transactions.

Soon after, he transferred ownership of his website’s domain to someone else, and since then, Bitcoin has been self-sustaining in a recurring community with no input from Satoshi.

Bitcoin is open source and distributed around the world. The blockchain is public, transparent, verifiable, auditable, and analyzable. Businesses can analyze the entire blockchain to see which bitcoins move or stay at different addresses. An open source full node can be run on a basic home computer. It can audit Bitcoin's entire money supply and other metrics.

With this in mind, we can compare Bitcoin to the red flags of a Ponzi scheme.

Return on investment: No promises

Satoshi Nakamoto never promised any return on investment, let alone a high or stable return on investment. In fact, it is well known that Bitcoin was a highly volatile speculative activity in the first decade after its birth. In the first year and a half, there was no quotation for Bitcoin, and after that, its price fluctuated greatly.

Satoshi's online posts still exist, and he almost never talks about financial gain. He writes mostly about technical aspects, freedom, problems with the modern banking system, etc. Satoshi writes mostly like a programmer, occasionally like an economist, and never like a salesman.

We have to search deep to find examples of him discussing the potential value of Bitcoin. When he does talk about the potential value or price of Bitcoin, he talks very matter-of-factly about how to classify Bitcoin as inflationary or deflationary, and acknowledges that the outcome of this project is highly variable.

Looking for what Satoshi said about the value of Bitcoin, I found the following:

“ The production of new coins means that the money supply is increasing on schedule, but this does not necessarily lead to inflation. If the money supply increases at the same rate as the number of people using it, prices will remain stable. If the money supply does not increase as fast as the demand for it, deflation will occur and early holders of the currency will see an increase in the value of the currency. ”

---

“ It makes sense to buy some just in case. If enough people have the same idea, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you can pay a few cents to a website as effortlessly as putting coins in a vending machine, it will be very widely used. ”

---

“ In that sense, it’s more like a precious metal. Instead of the supply changing to keep the value constant, the supply is predetermined and the value changes accordingly. As the number of users increases, the value per coin also increases. It has the potential to form a positive feedback loop; as more users come in, the value goes up, which could attract more users to take advantage of the increasing value. ”

---

“ Perhaps it could circulate and acquire initial value, as you suggest, through people foreseeing its potential use in exchange. (I’d certainly like some) Perhaps collectors, anything fortuitous could spark it. I think the traditional definition of money is based on the assumption that with so many scarce things competing in the world, things with intrinsic value must outperform things without intrinsic value. But if there were nothing with intrinsic value in the world that could serve as money, only things that were scarce but had no intrinsic value, I think people would still accept something. (I use the word scarce here just to refer to the potential limited supply) ”

---

“ For something that is expected to increase in value, a rational market price already reflects the present value of the expected future increase in value. In your mind, you make a probabilistic estimate, weighing the chances of it continuing to increase. ”

---

“ I’m convinced that in 20 years, there will either be very large volumes or there will be no volumes. ”

---

“ Bitcoin has no dividends or possible future dividends, so it’s not like a stock. It’s more like a collectible or a commodity. ”

—— Quotes from Satoshi Nakamoto

Promises of unusually high or ongoing returns on investment are common red flags of Ponzi schemes, but Satoshi Nakamoto’s original Bitcoin made no such promises.

Bitcoin investors have often predicted very high prices over time (and so far, those predictions have been correct). Despite this, the project itself has not had those attributes from the outset.

Open Source: The Antithesis of Secrecy

Most Ponzi schemes rely on secrecy. If investors knew that an investment they had was actually a Ponzi scheme, they would try to withdraw their money immediately. Until the secret is discovered, the market cannot properly price the investment.

For example, investors in Bernie Madoff's scheme thought they owned various assets. In reality, the money that went out to earlier investors was simply repaid from the money that came in from new investors, rather than making money from actual investments. The investments listed on their statements were all fake, and it was nearly impossible for any of these customers to verify that the investments were fake.

Bitcoin works in the exact opposite way. Bitcoin is a distributed open source software that requires majority consensus to change, and every line of code is known and cannot be changed by any central authority. A key principle of Bitcoin is verification rather than trust. The software to run a full node can be downloaded and run for free on an ordinary personal computer, and can audit the entire blockchain and the entire money supply. It does not rely on any website, key data center or corporate structure.

So there are no "paperwork issues" or "difficulties in withdrawing funds" that are associated with the SEC's red flags of a Ponzi scheme. The whole point of Bitcoin is that it does not rely on any third party; it is immutable and self-verifiable. Bitcoin can only be transferred via a private key associated with a specific address, and if you transfer Bitcoin using a private key, no one can stop you from doing so.

Of course, there are some bad actors in the surrounding ecosystem. People who rely on others to keep their private keys (rather than keeping them themselves) sometimes lose Bitcoin due to improper custody, but this is not due to a malfunction of the core Bitcoin software. Third-party exchanges can be fraudulent or hacked. Phishing schemes or other fraudulent activities may trick people into giving away private keys or account information. But these have nothing to do with Bitcoin itself, and when people use Bitcoin, they must make sure they understand how the system works to avoid falling for scams in the ecosystem.

No pre-mining

As mentioned earlier, Satoshi mined almost all of his coins when the software was made public, and anyone else could mine them. He did not give himself any unique advantage to acquire coins faster or more efficiently than others, but had to expend computing power and electricity to acquire coins, which in the early days was essential to keep the network functioning. As mentioned earlier, the white paper was released before the launch, which would be unusual or risky if the goal was primarily personal monetary gain.

In stark contrast to Bitcoin’s unusually public and fair launch, many later cryptocurrencies did not follow the same principles. Specifically, many later coins had a bunch of pre-mines, meaning that developers gave tokens to themselves and their investors before the project was made public.

Ethereum developers offered 72 million tokens to themselves and investors before opening it to the public. That’s more than half of Ethereum’s current token supply. It was a crowdsale.

Ripple Labs pre-mined 100 billion XRP tokens, most of which are owned by Ripple Labs, and gradually began selling the remaining tokens to the public while still holding the majority of the tokens. It is currently being charged by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for selling unregistered securities.

In addition to these two tokens, there are countless other smaller tokens that were pre-mined and sold to the public.

In some cases, a case can be made in favor of a premine, though some are very critical of the practice. Just as startups offer equity to their founders and early investors, new protocols can offer tokens to their founders and early investors, and crowdfunding is a widely accepted practice. I will leave that debate to others. Few would dispute that early developers can get paid if their projects are successful, and that funding is helpful for early development. As long as there is full transparency, it is up to the market to decide what price is fair.

However, Bitcoin is far ahead of most other digital assets when it comes to disproving the idea of a Ponzi scheme. Satoshi showed the world how to do this months in advance with a white paper, and then released the project as open source on the first day of spendable tokens, without a premine.

The founders give themselves little mining advantage over other early adopters, which is undoubtedly the "cleanest" approach. Satoshi would have to mine the first coins with his computer like everyone else, and then spend none of them except to send some of his initial batches out for early testing. This approach increases the likelihood of becoming a viral phenomenon based on economic or philosophical principles rather than strictly wealth-based.

Unlike many other blockchains over the years, Bitcoin’s development has been spontaneous, driven by a rotating group of large stakeholders and voluntary user donations, rather than through a pre-mined or pre-funded pool of funds.

On the other hand, giving the majority of the initial tokens to yourself and initial investors, and then having later investors mine or buy them from scratch, opens more avenues for criticism and skepticism and starts to look more like a Ponzi scheme, whether or not it actually is.

Leaderless Growth

One of the really interesting things about Bitcoin is that it is a large digital asset that has thrived without centralized leadership. Satoshi Nakamoto created Bitcoin as an anonymous inventor, worked with others, continued to develop it in public forums for the first two years, and then disappeared. Since then, other developers have taken over the responsibility of continuing to develop and promote Bitcoin.

Some developers are very important, but none of them are indispensable to the continued development or operation of Bitcoin. In fact, even the second round of developers after Satoshi mostly moved on to other directions. Hal Finney died in 2014. Other ultra-early Bitcoin users are more interested in Bitcoin Cash or other projects at different stages.

As Bitcoin has continued to evolve, it has begun to take on a life of its own. The distributed development community and user base (and the market, when it comes to pricing various paths after a hard fork) have determined what Bitcoin is and what use it has. Over time, the narrative has changed and expanded, with market forces rewarding or punishing in various directions.

Over the years, the debate has centered on whether Bitcoin should be optimized for value storage or frequent transactions at the base layer, which has led to multiple hard forks that have devalued Bitcoin compared to the base layer. The market clearly prefers Bitcoin's base layer to optimize its value storage and wide transaction settlement network, optimize its security and decentralization, and allow frequent small transactions to be processed on the second layer.

All other blockchain-based tokens, including hard forks and tokens associated with entirely new blockchain designs, have followed in the footsteps of Bitcoin, the industry’s most autonomous project. Most token projects are still founder-led, often with a large premine and an uncertain future if the founders are no longer involved. Some of the shadiest tokens have paid to be listed on exchanges in an attempt to kick-start network effects. In contrast, Bitcoin has always had the most natural growth curve.

Unregistered investments and unlicensed sellers

The only items on the red flag list that might apply to Bitcoin are those involving unregulated investments. This doesn’t mean something is a Ponzi scheme; it just means there are red flags and investors should proceed with caution. Especially in the early days of Bitcoin, buying some magical internet currency is a high-risk investment for most people.

Bitcoin was designed to be permissionless, operate outside the established financial system, and be philosophically inclined toward libertarian crypto culture and sound money. For most of its life, it had a steeper learning curve than traditional investments because it relied on the intersection of software, economics, and culture.

Some SEC officials have said that Bitcoin and Ethereum are not securities (logically, they have not committed securities fraud). However, many other cryptocurrencies or digital assets are classified as securities, and some, such as Ripple Labs, have been accused of selling unregistered securities. The IRS treats Bitcoin and many other digital assets as commodities for tax purposes.

So, in the early days, Bitcoin may indeed be an unregistered investment, but currently, it has a place in tax laws and regulatory frameworks around the world. Regulation will change over time, but this asset has become mainstream. It is so mainstream that Fidelity and other custodians hold it for institutional clients, and JP Morgan has also set a price target for it.

Many people who haven’t studied the industry in depth lump all “cryptocurrencies” into one category. However, it’s important for potential investors to research the details and find the important differences.

Putting “cryptocurrency” in one category is like putting “stocks” in one category. Bitcoin is clearly different from other currencies in many attributes, and the way it was launched and maintained looks more like a movement or a protocol than an investment, but over time it has become one.

From there, one can examine the thousands of other tokens that have emerged since Bitcoin and draw their own conclusions. They range from well-intentioned projects to outright scams. However, it’s important to realize that even if real innovation is happening somewhere, it doesn’t mean the token associated with that project will necessarily have lasting value. If a token solves some new problem, its solution may eventually be repurposed as a layer of a larger protocol with greater network effects. Likewise, any investment in other tokens has an opportunity cost, which is the ability to buy more Bitcoin.

Chapter Summary: Clearly Not a Ponzi Scheme

Bitcoin was launched in the fairest way possible.

Satoshi first showed others how to do it in an academic sense with a white paper, then did it himself a few months later, and anyone could start mining with him within the first few days, as some early adopters did. Satoshi then distributed the development of the software to others, then disappeared, rather than continue to promote it as a charismatic leader, and has never cashed out to date.

Bitcoin has been an open-source and fully transparent project from the beginning, with the most organic growth trajectory in the industry, and the market has publicly priced it based on existing information.

Broad Definition of a Ponzi Scheme

Because the narrow definition of a Ponzi scheme obviously does not apply to Bitcoin, some people use a broader definition of a Ponzi scheme to assert that Bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme.

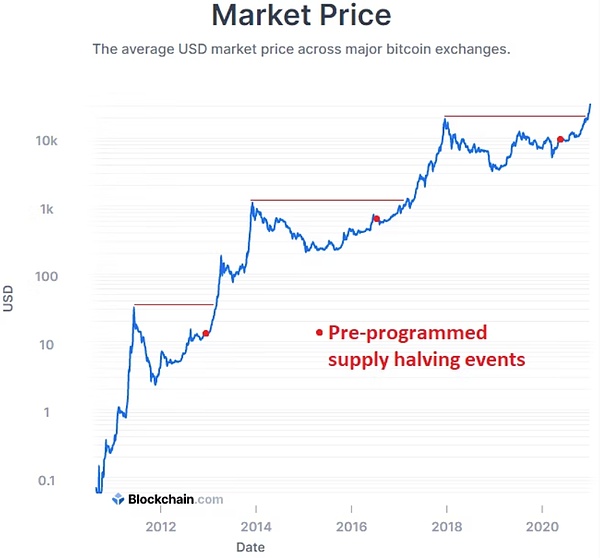

Bitcoin is like a commodity, a scarce digital "item" that provides no cash flow but has utility. They are limited to 21 million divisible units, of which more than 18.5 million have been mined on a pre-set schedule. Every four years, the number of new Bitcoins generated per ten-minute block will be halved, and the total number of Bitcoins in existence will gradually approach 21 million.

Like any commodity, it does not generate cash flows or dividends, and its value is determined only by what others are willing to pay you or trade with you. Specifically, it is a monetary commodity whose utility lies entirely in storing and transmitting value. This makes gold the closest comparable.

Bitcoin and the Gold Market

Some have asserted that Bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme because it relies on more and more investors entering the space, buying from early investors.

To some extent, this reliance on new investors is correct; Bitcoin’s network effects continue to grow, reaching more people and larger pools of capital, thereby continually increasing its utility and value.

Bitcoin can only be successful in the long term if its market cap reaches and remains at very high levels, in part because its security (hash rate) is tied to its price. If for some reason demand for Bitcoin permanently flattens and declines without reaching sufficiently high levels, Bitcoin will remain a niche asset. Its value, security, and network effects could deteriorate over time. This could spark a vicious cycle that attracts fewer developers to continue building its second layer and surrounding software and hardware ecosystem, potentially leading to stagnant quality, stagnant prices, and stagnant security.

However, this does not mean it is a Ponzi scheme, because by similar logic, gold is a 5,000-year-old Ponzi scheme. The vast majority of gold's uses are not for industry, but for storing and displaying wealth. It does not generate cash flow, it is only worth what someone else paid for it. If people's jewelry tastes change, if people no longer regard gold as the best store of value, its network effect may weaken.

It is estimated that the annual production of gold around the world is enough to meet all needs for more than 60 years. If jewelry and value preservation are excluded, this is equivalent to 500 years of industrial supply. Therefore, the balance of supply and demand for gold requires that people continue to see gold as an attractive way to store and display wealth, which is somewhat subjective. Based on industrial demand, there is an oversupply of gold and the price will be much lower.

However, the reason gold’s monetary network effects have remained strong for so long is that it possesses a unique set of properties that have led it to continue to be considered the best choice for long-term wealth preservation and cross-generational jewelry: it is scarce, beautiful, malleable, fungible, divisible, and virtually chemically indestructible. As global fiat currencies come and go, with each unit increasing rapidly in quantity, gold’s supply remains relatively scarce, growing by only about 1.5% per year.

Industry estimates put the world's above-ground gold reserves at about one ounce per person.

Likewise, Bitcoin relies on network effects, meaning that enough people need to see it as a good asset to maintain its value. But network effects themselves are not a Ponzi scheme. Potential investors can analyze indicators of Bitcoin's network effects and determine for themselves the risk/reward of buying Bitcoin.

Bitcoin and the Fiat Banking System

According to the broadest definition of a Ponzi scheme, the entire global banking system is a Ponzi scheme.

First, fiat money is in some sense an artificial commodity. The dollar itself is just a piece of paper, or representation on a digital bank ledger. The same is true for the euro, yen, and other currencies. It itself does not generate cash flows, although the institution that holds it for you may be willing to pay you a yield (or in some cases may charge you a negative yield). When we work or sell something to get dollars, we do so only because we believe that its broad network effects (including legal/governmental network effects) will ensure that we can hold these pieces of paper and hand them over to others in exchange for something of value.

Second, when we organize these pieces of paper and their digital representations in a fractional reserve banking system, we add another layer of complexity. If about 20% of people try to take their money out of the bank at the same time, the banking system will collapse. Or, more realistically, the bank will deny your withdrawal because they don't have the cash. This happened to some US banks during the pandemic lockdown in early 2020, and it happens frequently around the world. This is one of the SEC's warnings about Ponzi schemes: difficulty receiving payments.

In the famous game of musical chairs, there is a set of chairs, someone plays music, and the children (where there is one more child than there are chairs) start walking around the chairs in a circle. When the music stops, the children scramble to sit in one of the chairs. A child who is slow to react or has bad luck does not get a seat and therefore has to leave the game.

In the next round, one chair is removed and the music continues for the remaining child. Eventually, after multiple rounds, there are two children and one seat, and then a winner is created at the end of the round.

The banking system is a perpetual game of musical chairs. There are more kids than chairs, so they can't all get one. This would become clear if the music stopped. However, as long as the music keeps playing (with occasional bailouts via money printing), it will keep going.

Banks collect cash from depositors and use their capital to make loans and buy securities. Only a small portion of depositors' cash is available for withdrawal. Banks' assets include loans owed to them, securities such as Treasury bonds, and cash reserves. Their liabilities include money owed to depositors, as well as any other liabilities they may have, such as bonds issued to creditors.

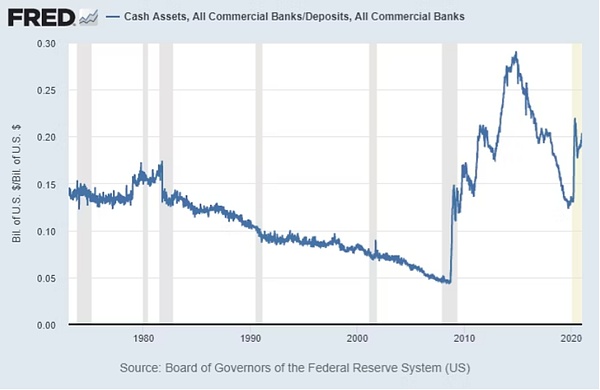

For the United States, banks collectively hold about 20% of customer deposits as cash reserves:

As the chart shows, before the global financial crisis this ratio was below 5% (which is why the crisis was so severe and marked a turning point in the long-term debt cycle), but with the implementation of quantitative easing, new regulations and more self-regulation, banks now hold about 20% of their deposit balances as reserves.

Likewise, the total amount of physical cash in circulation, printed exclusively by the U.S. Treasury, is only about 13% of total commercial bank deposits, and banks actually hold only a small fraction of that as vault cash. Physical cash is (by design) nowhere near enough for a significant number of people to withdraw funds from banks all at once.

If enough people do this at the same time, people will experience "difficulty in withdrawing funds".

The way it is currently constructed, the banking system will never end. If enough banks fail, the entire system will cease to function.

If a bank goes bankrupt without being bought out, it would theoretically have to sell all its loans and securities to other banks, convert them all into cash, and then pay out that cash to its depositors. But if enough banks do this at the same time, the market value of the assets they're selling will drop dramatically. The market will become illiquid because there won't be enough buyers.

In reality, if enough banks were to liquidate at once, and the market froze up because sellers of debt/loans overwhelmed buyers, the Fed would end up creating new dollars to buy assets to re-liquidate the market, which would dramatically increase the amount of dollars in circulation. Otherwise, everything would nominally collapse because there wouldn't be enough units of currency in the system to support the liquidation of the banking system's assets.

The monetary system is thus like an ongoing game of musical chairs on a government-issued artificial commodity, where if everyone were to scramble for the money at the same time, there would be far more claims on the money (the children) than there is money (the chairs) currently available to them. The number of children and chairs is constantly increasing, but there are always far more children than chairs. Whenever part of the system breaks down, a few chairs are added to the round to keep the system going.

We think this is normal because we don’t think it will ever end. Fractional reserve banking has been operating globally for hundreds of years (first gold-backed, then fully fiat-based), albeit with occasional inflationary events along the way to partially reset it.

Over the past few decades, the value of each unit of fiat currency has depreciated by about 99% or more. This means that investors either need to earn an interest rate that exceeds the actual inflation rate (which is not happening yet), or they need to buy investments, which causes the value of stocks and real estate to inflate relative to their cash flow and drives up the prices of scarce items such as art.

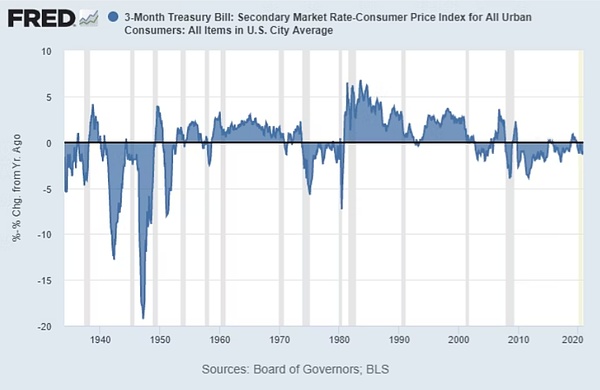

Over the past century, Treasury bonds and bank cash have simply kept pace with inflation, providing no real return. However, this has often been very volatile. In decades like the 1940s, 1970s, and 2010s, holders of Treasury bonds and bank cash have consistently failed to keep pace with inflation. This chart shows nine decades of Treasury bond rates minus the official inflation rate:

Bitcoin is an emerging deflationary savings and payment technology that is primarily used in an unleveraged manner, meaning most people just buy, hold, and occasionally trade. Some Bitcoin banks and some people on exchanges use leverage. Still, the system's overall debt is low relative to market value, and you can self-custody your assets.

Friction Cost

Another way to say it is a Ponzi scheme is that Bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme because it has friction costs. The system requires constant work to keep going.

However, Bitcoin is like any other commercial system in this respect. A healthy transaction network has inherent friction costs.

With Bitcoin, miners invest in custom hardware, electricity, and personnel to support Bitcoin mining, which means validating transactions and earning Bitcoin and transaction fees.

Miners take on a lot of risk and are rewarded with a lot of money, and they are necessary for the system to work. There are also market makers who provide liquidity between buyers and sellers or convert fiat currencies into Bitcoin, making it easier to buy and sell Bitcoin, and they will inevitably charge transaction fees.

Some institutions offer custodial solutions: holding your Bitcoin for a small fee.

Likewise, gold miners invest a lot of money into people, exploration, equipment, and energy to extract gold from the ground. Companies then purify it and mint it into bars and coins, protect and store it for investors, ship it to buyers, verify its purity, make it into jewelry, melt it down to purify and re-mint it, etc.

Gold atoms are constantly in circulation in all forms, thanks to the efforts of those in the gold industry, from the finest Swiss minters to high-end jewelers to bullion dealers and “we buy gold!” pawn shops. Gold’s energy work is biased toward creation rather than maintenance, but the industry also has these ongoing frictional costs.

Likewise, the global fiat currency system has friction costs. Banks and fintech firms collect more than $100 billion annually in transaction fees related to payments, act as custodians and managers of customer assets, and provide liquidity as market makers between buyers and sellers.

For example, I recently analyzed DBS Group Holdings, the largest bank in Singapore. They incur about S$900 million in fees per quarter, which is over S$3 billion per year. In US dollars, that's over $2.5 billion per year.

This is a bank with a market cap of $50 billion. Singapore has two other banks of comparable size. JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the US, is more than seven times as big, and there are several banks in the US that are similar in size. Visa and Mastercard alone have annual revenues of around $40 billion. Globally, banks and fintechs generate a combined annual fee of more than $100 billion.

Verifying transactions and storing value requires work, so any monetary system has friction costs. Friction costs only become a problem when transaction fees are a high percentage of payments. Compared to existing monetary systems, Bitcoin’s friction costs are quite low, and Layer 2 can continue to reduce fees further.

For example, Strike App aims to be the cheapest global payment network running on the Bitcoin/Lightning Network.

This extends to non-monetary goods as well. In addition to gold, wealthy investors store wealth in a variety of non-cash flow-generating items, including fine art, fine wines, classic cars, and ultra-high-end oceanfront properties that they can’t rent out. For example, there are certain beaches in Florida or California that have nothing but $30 million homes and are completely empty at all times. I love going to those beaches because they’re usually empty.

These scarce items tend to appreciate in value over time, which is why people hold them. However, they incur friction costs when you buy, sell, and maintain them. As long as these friction costs are lower than the average appreciation rate over time, they are good investments compared to holding fiat currencies, and not Ponzi schemes.

Chapter Summary: Network Effects, Not Ponzi Schemes

The broadest definition of a Ponzi scheme is any system that must continue to operate to remain functional or has frictional costs.

Bitcoin doesn’t actually fit this broader definition of a Ponzi scheme, just like the gold market, the global fiat banking system, or less liquid markets like art, fine wine, collectible cars, or beachfront property. In other words, if your definition of something is so broad that it includes all non-cash flow stores of value, then you need a better definition.

All of these scarce items have some utility in addition to their store of value properties. Gold and art allow you to enjoy and display visual beauty. Wine allows you to enjoy and display taste beauty. Collectible cars and beachfront homes allow you to enjoy and display graphic and tactile beauty. Bitcoin enables you to make domestic and international settlement payments without any direct mechanism blocked by third parties, providing users with unparalleled financial liquidity.

These scarce items maintain or increase in value over time, and investors are willing to pay a small friction cost as a percentage of their investment rather than hold fiat cash whose value will depreciate over time.

Yes, Bitcoin needs to continue to operate and must reach a sizable market cap for the network to be sustainable, but I think this is best viewed as a technological disruption that investors should price based on their perception of its probability of success or failure. This is a network effect that competes with existing network effects, especially in the global banking system, which ironically exhibits more Ponzi scheme characteristics than any other system on this list.

Final Thoughts

Any new technology goes through a period of evaluation and is either rejected or accepted. Markets may be irrational at first and move up or down, but over time assets are evaluated and measured.

Bitcoin’s price rises rapidly with each four-year supply halving cycle as its network effects continue to compound while supply remains limited.

Every investment carries risks, and of course, the ultimate fate of Bitcoin remains to be seen.

If the market continues to view it as a useful savings and payment settlement technology, accessible to most of the world’s population and backed by decentralized consensus around an immutable public ledger, then it can continue to capture market share as a store of wealth and settlement network until it reaches maturity, widespread adoption, and a low-volatility market cap.

On the other hand, naysayers often assert that Bitcoin has no intrinsic value and that one day everyone will realize what it is and it will go to zero.

However, rather than using this argument, a more sophisticated bear thesis would be that for some reason Bitcoin will not achieve its goal of taking lasting market share from the global banking system, and cite the reasons why they hold this view.

2020 is a story about institutional acceptance, with Bitcoin seemingly transcending the line between retail investment and institutional allocation. MicroStrategy and Square became the first public companies on major stock exchanges to allocate some or all of their reserves to Bitcoin instead of cash. MassMutual became the first major insurance company to put some of its assets into Bitcoin. Paul Tudor Jones, Stanley Druckenmiller, Bill Miller and other well-known investors are optimistic about Bitcoin. Some institutions such as Fidelity have been eyeing institutional custody services for Bitcoin for years, but in 2020, more institutions have joined in, including BlackRock, the world's largest asset manager, which has shown strong interest.

In terms of utility, Bitcoin allows for self-custody, money movement, and permissionless settlement. While there are other interesting blockchain projects, no other cryptocurrency offers a similar degree of security against attacks on its ledger (either in terms of hash rate or node distribution), nor does it have a sufficiently broad network effect to be consistently recognized as a store of value by the market with a high probability.

Importantly, Bitcoin’s growth has been the most organic in the industry, it took the lead and spread quickly without centralized leadership and promotion, making it more like a foundational protocol than a financial security or business project.