Author: Research Report; Source: Research Report Reading

The rapid growth of the US national debt has attracted widespread attention. According to the latest forecast by Bank of America, if the US debt continues to grow at the same pace as the past 100 days (an increase of $907 billion), the total US national debt will exceed $40 trillion on February 6, 2026. This figure is staggering - it took the US more than 200 years to accumulate the first $10 trillion in debt, and now it may add another $10 trillion in just 400 days.At the same time, US government spending grew 11% year-on-year to $7 trillion, and there are no signs of this fiscal expansion trend improving in the short term.

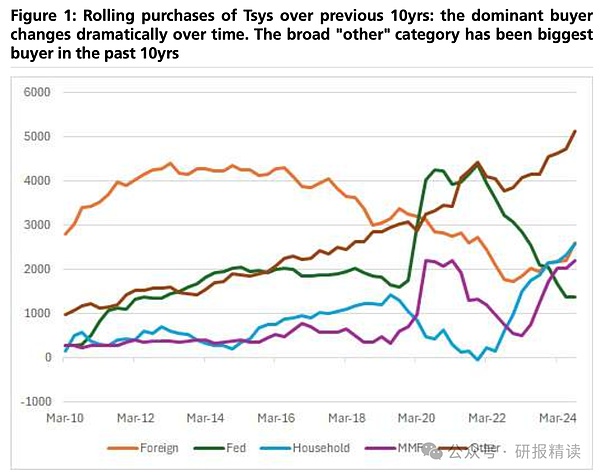

Faced with such a huge supply, the market naturally wonders: who will buy these bonds? Especially with the Federal Reserve continuing to push forward with quantitative tightening (QT), institutional investors, traditionally seen as the main buyers, face great uncertainty in their purchasing ability and willingness.

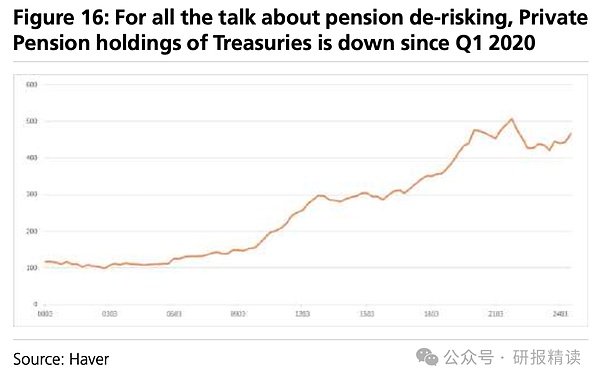

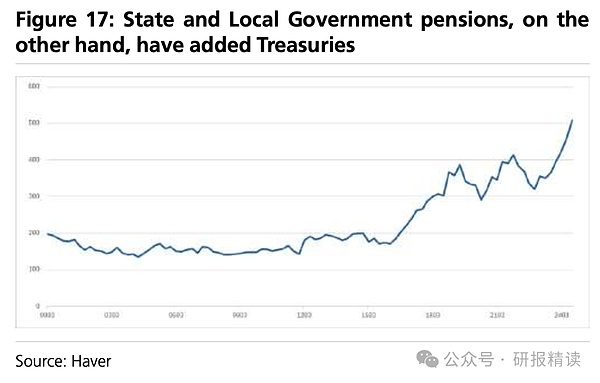

PART ONE Buyer 1: Pension Funds and Insurance Companies

Let's first look at the two major institutional investors, pension funds and insurance companies. Although they manage trillions of dollars in assets, they are not actually enthusiastic about directly purchasing US Treasuries. For example, private pension funds only hold 3% of their total assets in US Treasuries, and state and local government pension funds have about 5% in US Treasuries.These institutions tend to use derivatives to gain exposure to interest rate risk, and invest their cash in higher-yielding credit bonds and structured products.Life insurance companies' holdings of US Treasuries have remained stable over the past 25 years, with no significant growth. Even property insurance companies, whose liquidity needs have recently increased due to extreme weather, only doubled their US Treasury holdings from a relatively low level as a percentage of total assets.

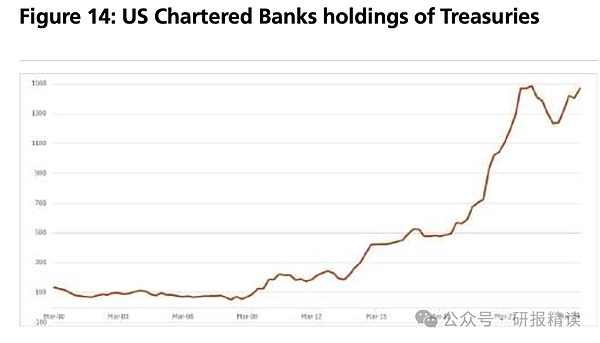

PART TWO Buyer 2: Banks

The situation with banks is also interesting. On the surface, the proportion of US Treasuries held by banks has risen from less than 2% of their total assets before the 2008 financial crisis to 6% now, but this is mainly due to regulatory requirements. In fact,banks do not take on too much interest rate risk, as they often hedge the interest rate risk of their long-term US Treasury holdings through asset swaps.Regulators also do not want banks to take on too much interest rate risk. Even if regulations are relaxed in the future, such as excluding US Treasuries from the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) calculation, this would mainly improve the liquidity of the US Treasury repo market, rather than significantly increase banks' actual demand for US Treasuries.

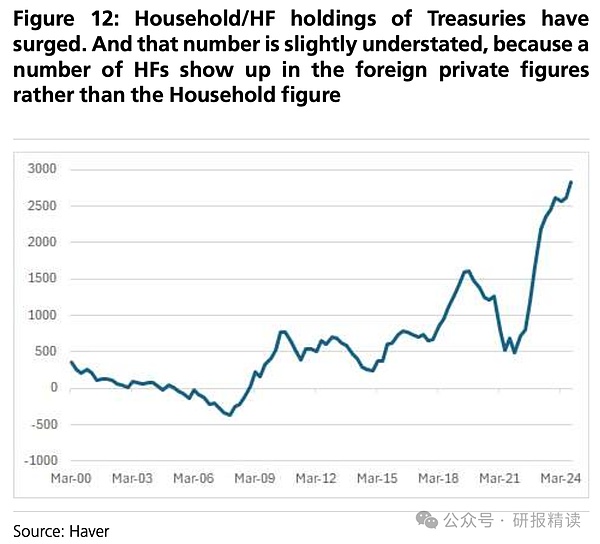

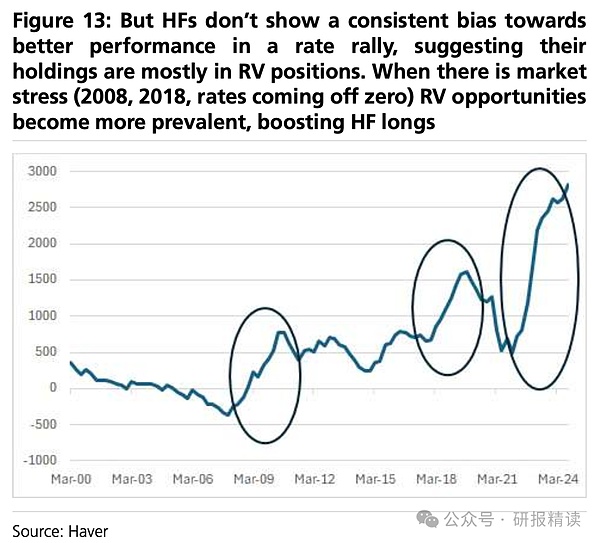

PART THREE Buyer 3: Hedge Funds

Hedge funds have indeed increased their holdings of US Treasuries recently, playing an important role in providing market liquidity. However, it should be noted that their positions are often based on various arbitrage trades, and do not represent long-term demand for US Treasuries. From the statements of regulatory authorities such as the BIS, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Canada, they are actually concerned about the growing intermediary role of hedge funds in the US Treasury market. Once market volatility increases or regulation tightens, hedge funds are likely to be forced to reduce their US Treasury holdings.

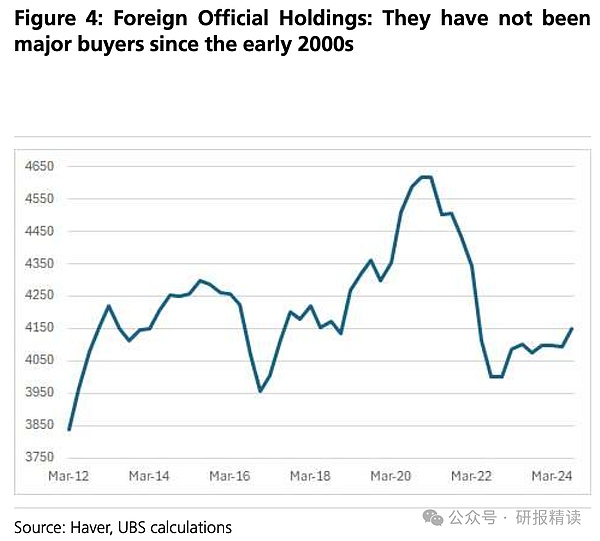

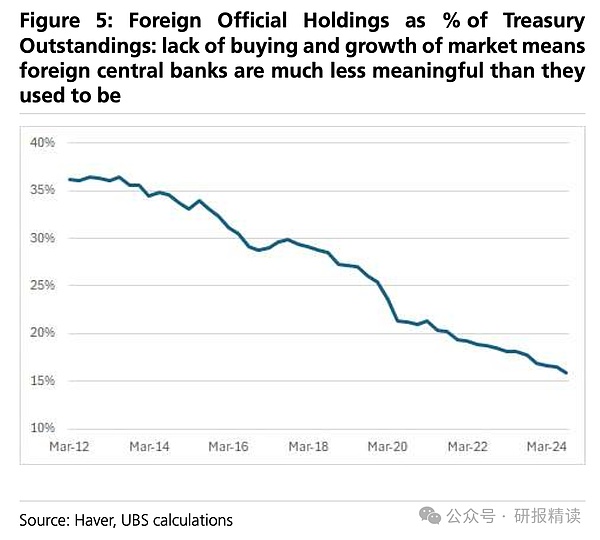

PART FOUR Buyer 4: Foreign Central Banks

Foreign central banks were once one of the most important buyers of US Treasuries.In the early 2000s, countries like Japan and China accumulated large US dollar assets and invested in US Treasuries to maintain exchange rate stability.But the situation has fundamentally changed now - in an environment of a strong US dollar, many central banks have to sell US Treasuries to obtain US dollars to maintain the exchange rate of their own currencies.Some central banks have even pre-positioned large amounts of US dollars in the Federal Reserve's reverse repurchase (RRP) facility to cope with potential exchange rate pressures.Unless the US dollar weakens significantly, the demand for US Treasuries from foreign official sectors is expected to remain weak.

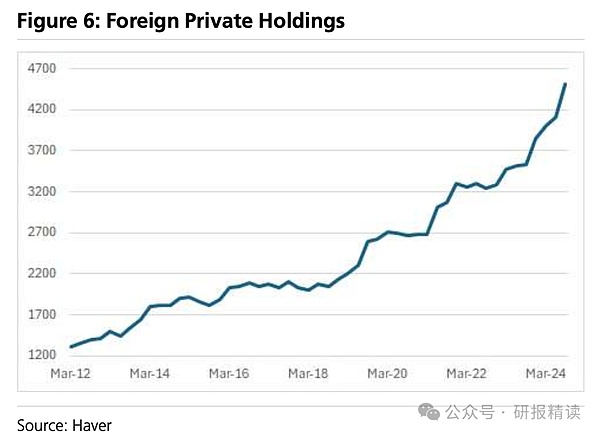

PART FIVE Buyer 5: Overseas Private Investors

As for whether overseas private investors are willing to buy US Treasuries, it mainly depends on two factors: the relative attractiveness of the yield and the exchange rate risk.

Let's use a simple example to illustrate this. Suppose a Japanese investor is considering buying Japanese government bonds or US Treasuries. If the yield on Japanese government bonds is 1% and the yield on US Treasuries is 4%, buying US Treasuries seems more profitable. But the problem is not that simple, because this investor faces exchange rate risk - if the US dollar depreciates 10% against the Japanese yen during the holding period, the 4% yield may turn into an actual loss of 6%.

To hedge this exchange rate risk, investors can use financial derivatives. But hedging has a cost, and this cost mainly depends on the shape of the interest rate curves of the two countries. Simply put, if the long-term interest rate in the US is much higher than the short-term interest rate (i.e. the yield curve is steep), the hedging cost will be relatively low; conversely, if the US long-term and short-term interest rates are similar (i.e. the yield curve is flat), the hedging cost will be higher.

In recent years, the US Treasury yield curve has been relatively flat compared to other developed markets. This means that if overseas investors fully hedge the exchange rate risk, they may not be better off buying US Treasuries than bonds in their own country. For example, if a European investor's actual yield on a 10-year US Treasury after hedging the exchange rate risk is only 2%, while the yield on a 10-year German government bond is 2.5%, then buying US Treasuries would clearly lack appeal.

Of course,if investors are optimistic about the US dollar outlook, they may choose not to hedge the exchange rate risk or only hedge a portion of it. Indeed, many overseas investors have done so in the context of the US dollar's sustained strength in recent years.But this strategy also has risks - if the US dollar starts to weaken, these investors may have to start hedging the exchange rate risk, and once they start hedging, the yield advantage of holding US Treasuries may vanish. In this case, they are likely to choose to reduce their US Treasury holdings and invest in other assets.

In short, for overseas private investors, buying US Treasuries not only requires considering the surface-level yield, but also weighing the exchange rate risk and hedging costs. In the current market environment, these factors combined may dampen their enthusiasm for buying US Treasuries. This is why the market is concerned that overseas private investors may not be a stable buyer as the supply increases significantly.

In summary, as the supply increases significantly, the purchasing power and willingness of traditional buyers are facing challenges.This supply-demand imbalance means that US Treasuries may need to offer higher yields to attract sufficient demand.Of course, if economic growth slows, the demand for safe-haven assets may drive various investors to increase their holdings of US Treasuries.Regulatory reforms could also theoretically create some new demand, but UBS analysis suggests this effect may be limited. In the current macroeconomic environment, the realization of a US Treasury supply-demand balance remains highly uncertain.

What worries the market even more is that such a huge debt burden also brings potential default risk.Although the possibility of a sovereign debt default by the US, as the world's largest economy and the issuer of the US dollar, is extremely low, even a short-term technical default could trigger severe financial market turmoil.

This is because US Treasuries play a unique and critical role in the global financial system. It is not only the most important "safe asset" globally, but also the benchmark for pricing in financial markets, and plays a core role in collateral-backed and derivative transactions. For example, in the repo market, US Treasuries are the main collateral, supporting trillions of dollars in short-term financing every day. If the US Treasuries default, this market could immediately collapse.

In addition, US Treasuries are also the most important liquidity reserve for global financial institutions. Banks, insurance companies, pension funds and other institutions all hold a large amount of US Treasuries as a liquidity buffer. If the price of US Treasuries experiences violent fluctuations or liquidity dries up, these institutions may be forced to sell assets, triggering a chain reaction. Especially given the generally high global debt levels at present, violent fluctuations in the US Treasuries market could be transmitted to other markets through various channels, triggering a broader financial crisis.

Historically, the US experienced a brief, small-scale debt default in 1979 due to technical reasons, and the impact was quite significant - it caused a 60 basis point spike in short-term Treasury yields, and the financing costs in the Treasury market remained under pressure for months afterwards. Now the size and interconnectedness of the US Treasuries market are far beyond what they were back then, and if a similar situation occurs, the impact will be more far-reaching.

Therefore, ensuring the smooth operation of the US Treasuries market is not only related to the fiscal situation of the US itself, but also to global financial stability. This is also why there is such a focus on the imbalance between supply and demand for US Treasuries. Against this backdrop, the US government, the Federal Reserve, and major market participants all need to act cautiously, both controlling the pace of debt growth and maintaining market confidence to avoid violent fluctuations. At the same time, other countries also need to be prepared, moderately diversifying their reserve assets, and enhancing the resilience of the financial system.

This tug-of-war over US Treasuries, not only concerns the sustainability of US fiscal policy, but also the stability of the global financial system. As the size of US Treasuries continues to expand, market attention to this issue will only increase further.