Original Title: AI as the engine, humans as the steering wheel

Author: Vitalik, Ethereum co-founder; Compiled by Baishuai, Jinse Finance

Special thanks to Devansh Mehta, Davide Crapis, and Julian Zawistowski for their feedback and review, as well as discussions with Tina Zhen, Shaw Walters, and others.

If you ask people what they like about democratic structures, whether in government, the workplace, or blockchain-based DAOs, you often hear the same arguments: they avoid concentration of power, they provide strong guarantees for users because no one can completely change the direction of the system at will, and they can make higher-quality decisions by aggregating the views and wisdom of many people.

If you ask people what they dislike about democratic structures, they often give the same complaints: ordinary voters are not sophisticated enough, because each voter has only a small chance of influencing the outcome, few voters invest high-quality thinking in decision-making, and you often get low participation (making the system vulnerable to attack) or de facto centralization, as everyone defaults to trusting and copying the views of some influential people.

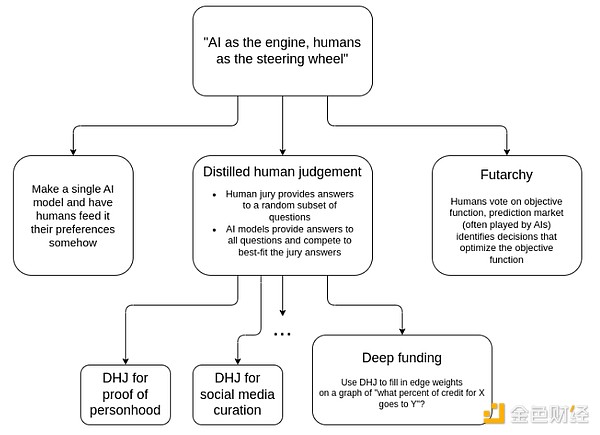

This article aims to explore a paradigm that may allow us to reap the benefits of democratic structures without the downsides. "AI as the engine, humans as the steering wheel". Humans only provide the system with a small amount of information, perhaps just a few hundred, but all of high quality and well-considered. The AI will treat this data as the "objective function" and make a vast number of decisions tirelessly, striving to achieve these goals to the best of its ability. In particular, this article will explore an intriguing question: can we achieve this without placing any single AI at the center, but rather relying on a competitive open market in which any AI (or human-AI hybrid) can freely participate?

Table of Contents

Why not just let an AI be in charge?

Futarchy

Refining human judgment

Deep funding

Increasing privacy

Benefits of engine + steering wheel design

Why not just let an AI be in charge?

The simplest way to inject human preferences into an AI-based mechanism is to create an AI model and have humans input their preferences into it in some way. There are simple ways to do this: you just need to put a text file containing a list of human instructions into the system prompt. Then, you can use one of the many "agent AI frameworks" to give the AI the ability to access the internet, hand it the keys to your organization's assets and social media profiles, and you're done.

After a few iterations, this may be sufficient to meet the needs of many use cases, and I fully expect that in the not-too-distant future, we will see many structures involving AIs reading instructions given by groups (or even reading real-time group chats) and taking action.

The problem with this structure is that it is not ideal as a long-term governance mechanism for institutions. A precious attribute that long-term institutions should have is trusted neutrality. In my post introducing this concept, I listed four precious attributes of trusted neutrality:

Do not hard-code specific people or specific outcomes into the mechanism

Open-source and publicly verifiable execution

Keep it simple

Don't change it often

LLMs (or AI agents) satisfy 0/4. The model inevitably encodes a huge amount of specific person and outcome preferences in its training process. Sometimes this leads to surprising AI preferences, like a recent study showing that major LLMs care more about the lives of Pakistanis than Americans (!!). It may have open weights, but this is far from open-source; we really don't know what demons are lurking in the depths of the model. It is the opposite of simple: the Kolmogorov complexity of an LLM is in the billions of bits, roughly equivalent to the total of all US law (federal + state + local). And because AI is evolving rapidly, you'd have to change it every three months.

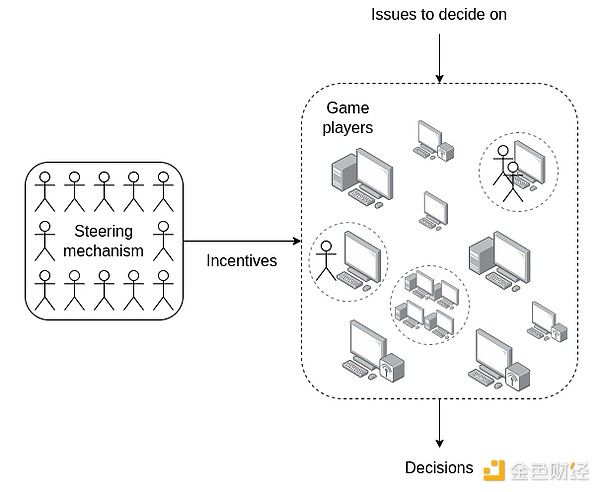

For this reason, I advocate exploring another approach in many use cases, where a simple mechanism becomes the rules of the game, and AI becomes the players. This is the insight that makes markets so effective: the rules are a relatively stupid property rights system, with the edge cases adjudicated by a court system that slowly accumulates and adjusts precedents, while all the intelligence comes from the entrepreneurs "operating at the edges".

Individual "game players" can be LLMs, groups of interacting and calling various internet services LLMs, various AI + human combinations, and many other constructs; as a mechanism designer, you don't need to know. The ideal goal is to have a mechanism that can run automatically -- if the mechanism's goal is to choose what to fund, it should be as automatic as Bitcoin or Ethereum block rewards.

The benefits of this approach are:

It avoids incorporating any single model into the mechanism; instead, you'll get an open market of many different participants and architectures, each with their own biases. Open models, closed models, agent pools, human + AI hybrids, bots, infinite monkeys, etc. are all fair game; the mechanism doesn't discriminate against any of them.

The mechanism is open-source. While the players are not, the game is -- and this is a pattern that has already been quite well understood (e.g. political parties and markets operate this way)

The mechanism is simple, so there are relatively fewer ways for the mechanism designer to encode their biases into the design

The mechanism doesn't change, even if the underlying participant architectures need to be redesigned from scratch every three months from now until the singularity.

The goal of the guiding mechanism is to faithfully reflect the fundamental objectives of the participants. It only needs to provide a small amount of information, but it should be high-quality information.

You can think of the mechanism as leveraging the asymmetry between proposing answers and verifying answers. This is similar to how Sudoku is hard to solve, but very easy to verify the solution is correct. You (i) create an open market with players acting as "solvers", and then (ii) maintain a human-operated mechanism that performs the much simpler task of executing the solutions that have been proposed.

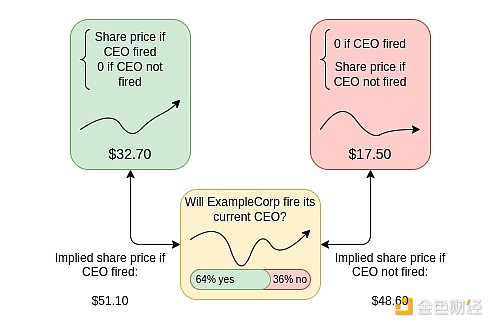

Futarchy

Futarchy, originally proposed by Robin Hanson, means "vote values, but bet beliefs". The voting mechanism selects a set of objectives (which can be anything, but the premise is that they must be measurable), and then combines them into a metric M. When you need to make a decision (for simplicity, let's assume it's a YES/NO decision), you set up a conditional market: you ask people to bet (i) whether YES or NO will be chosen, (ii) the value of M if YES is chosen, otherwise zero, (iii) the value of M if NO is chosen, otherwise zero. With these three variables, you can determine whether the market believes YES or NO is more favorable for the value of M.

"Company stock price" (or for cryptocurrencies, token price) is the most commonly cited metric, as it is easy to understand and measure, but the mechanism can support a variety of metrics: monthly active users, median self-reported happiness of certain groups, some quantifiable decentralization metrics, etc.

Here is the English translation of the text, with the specified terms retained and not translated:Futarchy was invented before the era of artificial intelligence. However, Futarchy naturally fits the "complex solver, simple verifier" paradigm described in the previous section, and the traders in Futarchy can also be artificial intelligence (or a combination of human and artificial intelligence). The role of the "solver" (prediction market traders) is to determine how each proposed plan will affect the value of future indicators. This is difficult. If the solvers are correct, they will make money, and if they are wrong, they will lose money. The verifiers (those who vote on the indicators, and who will adjust the indicators if they notice the indicators being "manipulated" or becoming outdated, and determine the actual value of the indicators at some future time) only need to answer a simpler question: "What is the current value of this indicator?"

Refining Human Judgment

Refining human judgment is a class of mechanisms that work as follows. There are a large number (think: 1 million) of questions that need to be answered. Natural examples include:

How much credit should each person on this list receive for a certain project or task?

Which of these comments violate the rules of the social media platform (or sub-community)?

Which of these given Ethereum addresses represent real and unique individuals?

Which of these physical objects make a positive or negative aesthetic contribution to their environment?

You have a team that can answer these questions, but the cost is that they have to expend a lot of effort on each answer. You only require the team to answer a small number of questions (for example, if the total list has 1 million items, the team might only answer 100 of them). You can even ask the team indirect questions: don't ask "What percentage of the total credit should Alice receive?", but rather "Should Alice or Bob receive more credit, and by how much?".

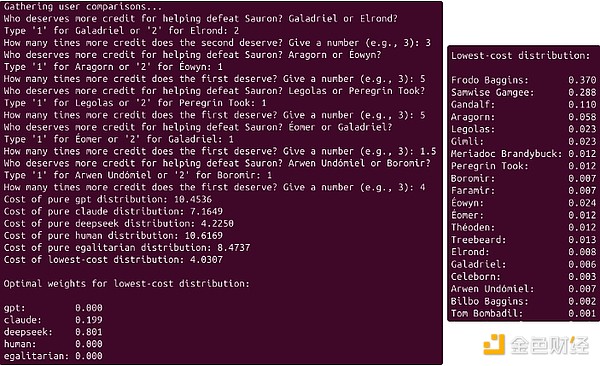

Then, you allow anyone to submit a numeric answer list for the entire question set (for example, providing an estimate of how much credit each participant in the entire list should receive). You encourage participants to use artificial intelligence to complete this task, but they can use any technology: artificial intelligence, human-machine hybrid, AI that can access the internet to search and autonomously hire other human or AI workers, cyborg-enhanced monkeys, etc.

Once both the full list providers and the jurors have submitted their answers, the full list will be checked against the jurors' answers, and a kind of combination of the full list that is most compatible with the juror answers will be taken as the final answer.

The refined human judgment mechanism differs from futarchy, but there are some important similarities:

In futarchy, the "solvers" make predictions, and the "true data" (used to reward or punish the solvers) that their predictions are based on is the output indicator values, run by a jury.

In refined human judgment, the "solvers" provide answers for a large number of questions, and the "true data" that their predictions are based on is the high-quality answers provided by the jury for a small subset of those questions.

A toy example of refined human judgment for credit allocation, see the Python code here. The script asks you to serve as the jury, and includes some pre-baked AI-generated (and human-generated) full lists. The mechanism identifies the linear combination of full lists that best fits the jury answers. In this case, the winning combination is 0.199 * Claude's answer + 0.801 * Deepseek's answer; this combination is more aligned with the jury answers than any single model. These coefficients will also be the rewards given to the submitters.

In this "defeating Sauron" example, the "humans as steering wheel" aspect manifests in two ways. First, high-quality human judgment is applied to each question, although this still leverages the jury as "technocratic" performance evaluators. Second, there is an implicit voting mechanism that determines whether "defeating Sauron" is the right target (rather than, say, trying to ally with Sauron, or ceding all the territory east of a key river as a peace concession). There are other refined human judgment use cases where the jury's task is more directly value-laden: for example, imagine a decentralized social media platform (or sub-community) where the jury's job is to label randomly selected forum posts as complying or not complying with community rules.

In the refining human judgment paradigm, there are some open variables:

How to do the sampling? The role of the full list submitters is to provide a large number of answers; the role of the jurors is to provide high-quality answers. We need to choose jurors and select questions for the jurors in a way that maximizes the ability of model fit to juror answers to indicate overall performance. Some considerations include:

Expertise vs. Bias Tradeoff: Skilled jurors are often specialized in their domains, so letting them choose the content they rate will give you higher-quality inputs. On the other hand, too much choice may lead to bias (jurors favoring content connected to them) or sampling weaknesses (certain content systematically unrated)

Anti-Goodhart: There will be content that tries to "game" the AI mechanism, e.g., contributors generating large amounts of seemingly impressive but useless code. This means the jury can detect this, but static AI models won't detect it unless they try hard. One possible way to capture this behavior is to add a challenge mechanism, where individuals can flag such attempts, with a guarantee that the jury will judge it (thereby incentivizing AI developers to ensure they capture it correctly). If the jury agrees, the challenger gets a reward; if the jury disagrees, they pay a fine.

What scoring function do you use? One idea from the current deep funding pilots is to ask jurors "Should A or B receive more credit, and by how much?". The scoring function is score(x) = sum((log(x[B]) - log(x[A]) - log(juror_ratio)) ** 2 for (A, B, juror_ratio) in jury_answers): i.e., for each jury answer, it asks how far the ratio in the full list is from the ratio the juror provided, and adds a penalty proportional to the square of the distance (in log space). This is to indicate that the design space for scoring functions is rich, and the choice of scoring function is related to the questions you ask the jurors.

How do you reward the full list submitters? Ideally, you want to frequently give non-zero rewards to multiple participants, to avoid monopolization, but you also want the property that participants can't increase their reward by submitting the same (or slightly modified) answer set multiple times. One promising approach is to directly compute the linear combination of full lists that best fits the jury answers (with non-negative coefficients that sum to 1), and use those same coefficients to split the reward. There may be other approaches as well.

Overall, the goal is to adopt known effective, minimally biased, and time-tested human judgment mechanisms (e.g., imagine how the adversarial structure of the court system includes the disputing parties, who have a lot of information but are biased, and the judge, who has little information but may be unbiased), and use an open AI marketplace as a reasonable high-fidelity and very low-cost predictor of the outputs of those mechanisms (similar to how law school "clerks" work).

Deep Funding

Deep funding is the application of refined human judgment to filling in the weights on the "What percentage of X's credit belongs to Y?" graph.

The simplest way to illustrate this is with an example:

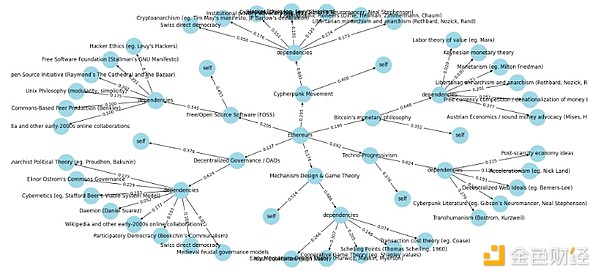

Output of a two-level deep funding example: The philosophical origins of Ethereum. See the Python code here.

The goal here is to allocate credit for the philosophical contributions to Ethereum. Let's look at an example:

This simulation of the deep funding rounds attributes 20.5% of the credit to the cypherpunk movement and 9.2% to technological progressivism.

At each node, you will pose a question: to what extent is it an original contribution (and thus deserving of credit for itself), and to what extent is it a recombination of other upstream influences? For the cypherpunk movement, it is 40% new and 60% dependent.

You can then look at the upstream influences on these nodes: libertarian minarchism and anarchism earned the cypherpunk movement 17.3% of the credit, but Swiss direct democracy only earned 5%.

But note that libertarian minarchism and anarchism also inspired the monetary philosophy of Bitcoin, so it influenced the philosophy of Ethereum through two paths.

To calculate the total share of contribution of libertarian minarchism and anarchism to Ethereum, you need to multiply the edge weights on each path and then sum the paths: 0.205 * 0.6 * 0.173 + 0.195 * 0.648 * 0.201 ~= 0.0466. So if you had to donate $100 to reward all contributors to Ethereum's philosophy, based on this simulation of the deep funding rounds, the libertarian minarchists and anarchists would receive $4.66.

This approach is intended to apply to domains where work is built on previous work and the structure is highly clear. Academia (think: citation graphs) and open-source software (think: library dependencies and forks) are two natural examples.

The goal of a well-functioning deep funding system is to create and maintain a global graph, where any funder interested in supporting a particular project can send funds to the address representing that node, and the funds will automatically propagate along the graph edges according to their weights (and recursively to their dependencies, etc.).

You can imagine a decentralized protocol using an embedded deep funding mechanism to issue its tokens: the decentralized governance within the protocol would select a jury, and the jury would run the deep funding mechanism, as the protocol would automatically issue tokens and deposit them into the nodes corresponding to itself. In doing so, the protocol programmatically rewards all of its direct and indirect contributors, reminiscent of how Bitcoin or Ethereum block rewards reward a particular type of contributor (miners). By influencing the edge weights, the jury can continually define the types of contributions it values. This mechanism can serve as a decentralized and long-term sustainable alternative to mining, sales, or one-time airdrops.

Increasing Privacy

Typically, to make proper judgments on the questions in the above example, access to private information would be required: internal chat logs of organizations, secret submissions from community members, etc. One benefit of a "single AI only" approach, especially in smaller-scale settings, is that it makes it more palatable for an AI to access information than to make it publicly available to everyone.

To enable refined human judgment or deep funding to operate in these cases, we can explore using cryptographic techniques to securely allow the AI to access private information. The idea is to use multi-party computation (MPC), fully homomorphic encryption (FHE), trusted execution environments (TEEs), or similar mechanisms to provide the private information, but only in a way that its sole output is directly fed into the mechanism as a "complete list submission".

If you do this, you must then restrict the mechanism set to AI models (rather than humans or AI+human combinations, since you cannot let humans see the data), and models specific to running on certain substrates (e.g., MPC, FHE, trusted hardware). A major research direction is to find sufficiently efficient and meaningful practical versions in the near term.

The Benefits of an Engine+Steering Wheel Design

This design has many promising benefits. The most important benefit so far is that it allows the construction of DAOs where human voters control the steering, but they are not burdened with too many decisions. It achieves a compromise where each person doesn't have to make N decisions, but they have power that is not just a single decision (as is typical with delegation), but can express richer preferences that are difficult to directly articulate.

Additionally, these mechanisms seem to have an incentive-smoothing property. By "incentive-smoothing" I mean a combination of two factors:

Diffusion: Any single action taken by the voting mechanism does not have an outsized impact on the interests of any single participant.

Obfuscation: The connection between voting decisions and how they impact participant interests becomes more complex and difficult to calculate.

These terms of diffusion and obfuscation are borrowed from cryptography, where they are key properties for the security of ciphers and hash functions.

A good real-world example of incentive-smoothing today is the rule of law: the top levels of government do not take actions like "give Alice's company $200 million" or "fine Bob's company $100 million", but rather through rules intended to be applied evenly across a large number of participants, then interpreted by another class of participants. When this system works, the benefit is that it greatly reduces the incentives for bribery and other forms of corruption. When it is violated (which happens often in practice), these problems can quickly become greatly amplified.

Artificial intelligence is clearly going to be an important component of the future, and it will inevitably become an important part of future governance. But if you let AI participate in governance, there are obvious risks: AI has biases, it can be deliberately corrupted in the training process, and AI technology is advancing so rapidly that "letting AI rule" may effectively mean "letting the people responsible for upgrading the AI rule". Refined human judgment provides an alternative path forward that allows us to harness the power of AI in an open, free-market way, while maintaining human control and democracy.