Author: Joel John, Decentralised.co

Compiled by: Yangz, Techub News

Money governs everything around us. When people start discussing fundamentals, the market is probably in a bad state.

This article raises a simple question: should tokens generate revenue? If so, should the team buy back their own tokens? As with most things, there is no clear answer to this question. The path forward requires paved by honest dialogue.

Life is but a game called capitalism

This article was inspired by a series of conversations with Ganesh Swami, co-founder of the blockchain data query and indexing platform Covalent. The content covers the seasonality of protocol revenue, the evolving business models, and whether token buybacks are the best use of protocol capital. This is also a supplement to my article last Tuesday about the current stagnation in the cryptocurrency industry.

Private capital markets like venture capital are always oscillating between excess liquidity and liquidity scarcity. When these assets become liquid and external capital continues to flow in, the industry's optimism often drives price increases. Think of all the new IPOs or token launches, where this newfound liquidity allows investors to take on more risk, but in turn also gives birth to a new generation of companies. As asset prices rise, investors turn to earlier-stage applications, hoping to achieve higher returns than benchmarks like Ethereum and SOL.

This phenomenon is a feature of the market, not a problem.

Source: Dan Gray, Chief Research Officer at Equidam

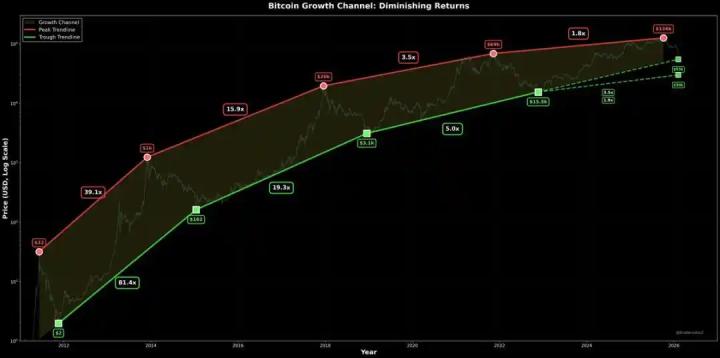

The liquidity in the cryptocurrency industry follows a cyclical pattern marked by Bitcoin's block reward halvings. Historically, market rallies typically occur within six months of a halving. In 2024, the inflow of funds into Bitcoin spot ETFs and Michael Saylor's large-scale purchases (he spent $22.1 billion on Bitcoin last year) will become a "reservoir" for Bitcoin. However, the rise in Bitcoin prices has not led to an overall rebound in smaller Altcoins.

We are currently in a period of tight capital liquidity, with capital allocators' attention divided among thousands of assets, while founders who have been working for years to develop tokens are also struggling to find meaning in all this, "if meme assets can bring more economic returns, why bother building real applications?"

In previous cycles, L2 tokens enjoyed a premium valuation due to perceived potential value, supported by exchange listings and venture capital. However, as more participants enter the market, this perception and valuation premium are being eroded. The result is a decline in the token value of L2s, which in turn limits their ability to subsidize smaller products through grants or token revenue. Furthermore, the overvaluation has in turn forced founders to grapple with the age-old question that plagues all economic activity: where does the revenue come from?

How Cryptocurrency Project Revenues Work

The image above nicely explains the typical workings of cryptocurrency project revenues. For most products, Aave and Uniswap are undoubtedly ideal templates. These two projects have maintained stable fee revenues for years, leveraging their early market entry advantage and the "Lindy effect". Uniswap can even create revenue by increasing front-end fees, perfectly embodying consumer preferences. Uniswap is to decentralized exchanges what Google is to search engines.

In contrast, projects like Friend.tech and OpenSea have more seasonal revenues. For example, the "NFT Summer" lasted for two quarters, while the speculative frenzy around Social-Fi only lasted for two months. For some products, speculative revenues can be understandable, provided the revenue scale is large enough and consistent with the product's original intent. Currently, many meme trading platforms have joined the club of generating over $100 million in fee revenue. This revenue scale is usually only achievable for most founders through token sales or acquisitions. For the majority of founders focused on developing infrastructure rather than consumer applications, this level of success is not common, and the revenue dynamics of infrastructure are also different.

During the period from 2018 to 2021, venture capital firms provided abundant funding for developer tools, expecting developers to gain a large user base. But by 2024, two major transformations have occurred in the cryptocurrency ecosystem:

First, smart contracts have achieved limitless scalability with minimal human intervention. Today, Uniswap and OpenSea no longer need to scale their teams proportionally to transaction volume.

Second, advancements in large language models (LLMs) and AI have reduced the investment demand for cryptocurrency developer tools. As an asset class, it is now in a "liquidation moment".

In Web2, the API-based subscription model worked because the online user base was massive. However, Web3 is a smaller niche market, with only a few applications able to scale to millions of users. Our advantage lies in the higher individual user revenue. Due to the ability of blockchain to facilitate fund flows, cryptocurrency users often spend more frequently and at higher amounts. Therefore, within the next 18 months, most businesses will have to redesign their business models to directly generate revenue from users in the form of transaction fees.

Of course, this is not a new concept. Initially, Stripe charged per API call, while Shopify charged a uniform subscription fee, but both platforms later switched to revenue-sharing models. For infrastructure providers in Web3, the API fee model is relatively straightforward. They undercut the API market through competitive pricing, even offering free products, until they reach a certain transaction volume, and then start negotiating revenue sharing. Of course, this is an ideal hypothetical scenario.

As for the actual situation, Polymarket is an example. Currently, the UMA protocol's tokens are tied to dispute cases and used to resolve disputes. The more prediction markets, the higher the probability of disputes occurring, directly driving the demand for UMA tokens. In the trading model, the required margin can be a small percentage, such as 0.10% of the total bet amount. Assuming a $1 billion bet on the presidential election outcome, UMA could generate $1 million in revenue. In the hypothetical scenario, UMA could use this revenue to buy back and burn its own tokens. This model has its advantages, but also faces certain challenges (which we will discuss further later).

In addition to Polymarket, another example of a similar model is MetaMask. Through the embedded swap functionality in this wallet, there is currently about $36 billion in transaction volume, with the swap business alone generating over $300 million in revenue. A similar model also applies to staking providers like Luganode, which can charge fees based on the staked asset amount.

Here is the English translation, with the terms in <> retained as is: However, in a market where API call revenues are increasingly declining, why would developers choose one infrastructure provider over another? If revenue sharing is required, why choose this oracle service over another? The answer lies in network effects. Data providers that support multiple blockchains, provide unparalleled data granularity, and can index new chains faster will become the preferred choice for new products. The same logic applies to transaction categories such as intent or Gas-free exchange tools. The more blockchains supported, the lower the cost and faster the speed, the more likely it is to attract new products, as marginal efficiency helps retain users.Token Buybacks and Burning

Tying token value to protocol revenue is not a new concept. In recent weeks, some teams have announced mechanisms to buy back or burn native tokens based on revenue ratios. Notable examples include Sky, Ronin, Jito, Kaito, and Gearbox. Token buybacks are akin to stock buybacks in the US stock market, essentially a way to return value to shareholders (token holders) without violating securities laws. In 2024, the funds used for stock buybacks in the US market alone are expected to reach around $790 billion, up from only $170 billion in 2000. Prior to 1982, stock buybacks were considered illegal. Over the past decade, Apple alone has spent over $800 billion buying back its own stock. While it remains to be seen whether this trend will continue, we are seeing a clear market differentiation between tokens with cash flow and a willingness to invest in their own value, and those without. Source: Bloomberg

For most early-stage protocols or dApps, using revenue to buy back their own tokens may not be the optimal use of capital. One viable approach is to allocate sufficient funds to offset the dilutive effect of new token issuance, which is precisely the explanation the Kaito founder recently provided for their token buyback method. Kaito is a centralized company that uses token incentives to grow its user base. The company receives centralized cash flow from enterprise clients and uses a portion of that cash flow to execute token buybacks through market makers. The number of tokens bought back is twice the number of newly issued tokens, effectively putting the network in a deflationary state.

In contrast to Kaito, Ronin takes a different approach. The chain adjusts fees based on the number of transactions per block. During peak usage periods, a portion of the network fees will flow into the Ronin treasury. This is a way to monopolize the asset supply without buying back tokens. In both cases, the founders have designed mechanisms to tie value to economic activity on the network.

In future articles, we will delve deeper into how these operations impact the pricing and on-chain behavior of the tokens involved in such activities. But for now, it is evident that as token valuations decline and the amount of venture capital flowing into the cryptocurrency industry decreases, more teams will have to compete for the marginal dollars entering our ecosystem.

Considering the core property of blockchain "monetary orbits", most teams will likely shift to a revenue model based on a percentage of transaction volume. When this happens, if the project team has already launched a token, they will have an incentive to implement a "buyback and burn" model. Those teams that can successfully execute this strategy will become winners in the liquid market, or they may buy back their tokens at a very high valuation. The outcomes can only be known in hindsight.

Of course, one day, all discussions about price, yield, and revenue will become irrelevant. We will once again pour our money into various "Doggy Memecoins" and purchase all sorts of "Monkey NFTs". But looking at the current state of the market, most survival-concerned founders have begun to engage in deep discussions around revenue and token burning.

Source: Bloomberg

For most early-stage protocols or dApps, using revenue to buy back their own tokens may not be the optimal use of capital. One viable approach is to allocate sufficient funds to offset the dilutive effect of new token issuance, which is precisely the explanation the Kaito founder recently provided for their token buyback method. Kaito is a centralized company that uses token incentives to grow its user base. The company receives centralized cash flow from enterprise clients and uses a portion of that cash flow to execute token buybacks through market makers. The number of tokens bought back is twice the number of newly issued tokens, effectively putting the network in a deflationary state.

In contrast to Kaito, Ronin takes a different approach. The chain adjusts fees based on the number of transactions per block. During peak usage periods, a portion of the network fees will flow into the Ronin treasury. This is a way to monopolize the asset supply without buying back tokens. In both cases, the founders have designed mechanisms to tie value to economic activity on the network.

In future articles, we will delve deeper into how these operations impact the pricing and on-chain behavior of the tokens involved in such activities. But for now, it is evident that as token valuations decline and the amount of venture capital flowing into the cryptocurrency industry decreases, more teams will have to compete for the marginal dollars entering our ecosystem.

Considering the core property of blockchain "monetary orbits", most teams will likely shift to a revenue model based on a percentage of transaction volume. When this happens, if the project team has already launched a token, they will have an incentive to implement a "buyback and burn" model. Those teams that can successfully execute this strategy will become winners in the liquid market, or they may buy back their tokens at a very high valuation. The outcomes can only be known in hindsight.

Of course, one day, all discussions about price, yield, and revenue will become irrelevant. We will once again pour our money into various "Doggy Memecoins" and purchase all sorts of "Monkey NFTs". But looking at the current state of the market, most survival-concerned founders have begun to engage in deep discussions around revenue and token burning.