By Guy Wuollet

Compiled by: TechFlow

Existing physical infrastructure networks, such as telecommunications, energy, water, and transportation, are often natural monopolies—markets where the cost of providing a product or service by a single company is far lower than what is needed to encourage competition. In most developed countries, these networks are governed by complex government regulations and rules. However, this model provides little incentive for innovation, let alone improving the customer experience, optimizing the user interface, improving service quality, or speeding up response times. Moreover, these networks are often inefficient and poorly maintained. For example, the California wildfires that bankrupted PG&E or regulatory policies that protect incumbent telecom companies are evidence of this. In developing countries, the situation is even worse: many of these services are either non-existent or expensive and scarce.

We can do better. Decentralized physical infrastructure networks offer us an opportunity to go beyond the existing monopoly system and build a more powerful, more investable, and more transparent network. The DePIN (Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Network) protocol is a user-owned and operated service that allows anyone to contribute to the core infrastructure that runs our daily lives. These protocols have the potential to become an important democratizing force to make society more efficient and open.

In this article, I will explain what DePIN is and why it is important. I will also share a framework for evaluating DePIN protocols and explore the questions that need to be asked when building DePIN protocols, especially the verification problem.

What is DePIN?

A Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Network (DePIN) is any sufficiently decentralized network that leverages cryptography and mechanism design to ensure that clients can request physical services from a set of service providers, thereby breaking natural monopolies and bringing the benefits of competition (we’ll explore this in more detail below). Clients are typically end users, but may also be applications operating on behalf of end users. Service providers are typically small businesses, but may also include gig workers or even large traditional companies, depending on the network. In this context, “decentralization” refers to the decentralization of power and control , not just the decentralization of physical distribution or data structures.

If designed properly, the DePIN protocol can encourage users and small businesses to participate in the physical infrastructure network and co-govern its development over time, while providing transparent incentives for contributions. Just as the Internet is dominated by user-generated content, DePIN provides an opportunity for the physical world to be dominated by user-generated services. More importantly, just as blockchain is breaking the "attract-extract" cycle of monopoly technology companies, the DePIN protocol can also help break the utility monopoly in the physical world.

DePIN in action: Energy grid

Take energy, for example . The U.S. energy grid is moving toward decentralization even in a non-encrypted environment. Transmission bottlenecks and long delays in connecting new generation capacity to the grid have led to a demand for decentralized generation capacity. Homes and businesses can deploy solar panels to generate electricity at the edge of the grid, or install batteries to store electricity. This means they can not only buy energy from the grid, but also sell energy back to the grid.

As edge generation and storage become more prevalent, many devices connected to the grid are no longer owned by utilities. These user-owned devices can greatly benefit the grid by storing and releasing energy at critical moments, so why are they not being fully utilized? Existing utilities cannot effectively obtain status information about these devices, nor can they purchase control over them. The Daylight Protocol is providing a solution to the fragmentation problem in the energy industry. Daylight is building a decentralized network that enables users to sell status information about their grid-connected devices and allows energy companies to temporarily control these devices for a fee. In short, Daylight is building a decentralized virtual power plant .

The result could be a stronger, more efficient energy grid with user-owned generation capacity, better data, and fewer trust assumptions than a centralized monopoly. That’s the promise of DePIN.

DePIN Construction Guide

The DePIN protocol has great potential to improve the core physical infrastructure we interact with every day, but to achieve this goal, at least three major challenges need to be overcome:

Determine whether decentralization is necessary in a particular situation;

Marketing;

Verification is the most challenging part.

I have deliberately ignored the specific technical challenges of any particular physical infrastructure domain. This is not because these challenges are unimportant, but because they are domain-specific. In this article, I focus on building decentralized networks at an abstract level and provide recommendations for all DePIN projects across different physical industries.

1. Why choose DePIN?

Two common reasons for building the DePIN protocol are to reduce capital expenditures (Capex) for hardware deployment and to aggregate decentralized resource capacity . In addition, the DePIN protocol can also create neutral developer platforms on top of physical infrastructure that can unlock permissionless innovations, such as open energy data APIs or neutral ride-hailing markets. Through decentralization , the DePIN protocol achieves censorship resistance, eliminates platform risk, and promotes permissionless innovation - this composability and permissionless innovation are the key reasons why Ethereum and Solana are booming. Traditionally, deploying physical infrastructure networks is costly and usually requires a centralized company to complete, while DePIN disperses costs and control through decentralized ownership.

1.1 Capital Expenditure (Capex)

Many DePIN protocols reduce the large or even unfeasible capital expenditures that are usually required of centralized companies by encouraging users to purchase hardware and participate in network operations. High capital expenditures are one of the reasons why many infrastructure projects are considered natural monopolies, and reducing capital expenditures provides a structural advantage for DePIN protocols.

Take the telecommunications industry, for example. The adoption of new network standards is often hampered by the high capital expenditures required to deploy new hardware. For example, one analysis predicts that deploying 5G cellular networks in the United States alone will require up to $275 billion in private investment.

In contrast, Helium, the DePIN network, has successfully deployed the world's largest long-range, low-power network ( LoRaWAN ) without a single entity making large-scale upfront hardware investments. LoRaWAN is a standard that is well suited for Internet of Things (IoT) use cases. Helium worked with hardware manufacturers to develop LoRaWAN routers, allowing users to purchase these routers directly from the manufacturers. These users then become the owners and operators of the network, providing services to customers who need LoRaWAN connectivity and getting paid for it. Currently, Helium is focusing on expanding its 5G cellular network coverage .

Deploying an IoT network like Helium does requires taking on a huge upfront capital expenditure risk and betting on whether there is a large enough customer base willing to purchase connectivity to the new network. However, as a DePIN protocol, Helium has validated its market supply side through decentralization and significantly reduced its cost structure.

1.2 Resource Capacity

In some cases, there is a large amount of potential idle capacity in physical resources, but it is difficult for existing companies to effectively integrate it due to complexity. For example, the free space on a hard drive. On any single hard drive, these spaces may be too small to attract the attention of storage companies like AWS. However, when aggregated through a DePIN protocol like Filecoin, these scattered spaces can be transformed into a cloud storage service provider. The DePIN protocol is able to use blockchain technology to coordinate the resources of ordinary users, allowing them to contribute to a large-scale network.

1.3 Permissionless Innovation

The most critical feature unlocked by the DePIN protocol is permissionless innovation: anyone can build on top of the protocol. This is in stark contrast to traditional monopolistic infrastructure such as the local power company grid. Compared to reducing capital expenditures or integrating resource capacity, the potential of permissionless innovation is often underestimated.

Permissionless innovation enables physical infrastructure to evolve at the speed of software. We often hear that the pace of innovation in the digital realm (“ bits ”) is amazing, while the pace of innovation in the physical realm (“ atoms ”) is disappointing. DePIN provides developers and investors with an important path for “atoms” to become more like “bits”. When anyone in the world with an internet connection can come up with new ways to organize and coordinate the physical systems that run our world, smart and creative people can invent solutions that are better than existing ones.

1.4 Composability

The reason why permissionless innovation can accelerate the transition from "atoms" to "bits" is composability . Composability allows developers to focus on building the best single point solution and make it easy to integrate. We have already witnessed this power in the "money legos" of decentralized finance (DeFi). In DePIN, "infrastructure legos" can have a similar impact.

2. Market launch: opportunities and challenges

Building a DePIN protocol is more difficult than building a blockchain because it requires solving the dual challenges of decentralized protocols and traditional businesses at the same time. Bitcoin and Ethereum started relatively independently of the traditional financial and cloud computing fields, while most DePIN protocols do not have such luxury conditions and are closely related to existing problems in the physical world.

Most DePIN fields have to interact with existing centralized systems from day one. Take utility companies, cable companies, ride-hailing services, and Internet service providers as examples. These existing networks are usually protected by regulatory policies and have strong network effects. It is often difficult for new entrants to compete. Just as decentralized networks are the natural antidote to Internet monopolies, DePIN networks are the natural antidote to physical infrastructure monopolies.

However, DePIN developers need to first find an entry point that can add value, and gradually expand with this goal, eventually challenging the existing physical network as a whole. Finding the right entry point is critical to future success. DePIN developers also need to understand how their network will interact with existing alternatives. Most traditional companies are resistant to running blockchain full nodes and often have difficulty handling self-custody or on-chain transactions. They often do not understand the meaning or value of encryption technology.

One way to do this is to demonstrate the value that the DePIN protocol can bring — without mentioning that it runs on crypto. When existing players seriously consider integration or are able to understand the value that new protocols bring, they will be more willing to embrace crypto. More broadly: developers should tailor the value proposition of the protocol to different audiences and design narratives that resonate emotionally with their audiences.

Tactically, interfacing with existing networks usually requires some degree of early mediation and thoughtful design of physical structures, which is highly dependent on the specific physical domain the protocol targets.

Enterprise sales are also a challenge for the DePIN protocol. Enterprise sales are often "white glove", time-consuming, and require customized services. Customers usually want a direct person who can be "held accountable". However, in the DePIN network, no individual or company can represent the entire network, and it is impossible to run a traditional enterprise sales process.

One solution is for the DePIN protocol to have centralized companies as initial distribution partners, who resell the services. For example, a centralized telecom company can sell services directly to regular consumers and charge USD fees, but the actual services are provided by the underlying decentralized telecom network. In this way, the complex crypto wallet and self-custody issues are abstracted, and the "crypto" features are hidden. This model of distributing DePIN network services by centralized companies can be called a "DePIN mullet", similar to the popular application of the " DeFi mullet " model in financial services.

3. Difficulty of DePIN: Verification

The hardest part of building the DePIN protocol is verification . Verification is crucial: it is the only definitive way to ensure that customers get the services they paid for, and that service providers get paid correctly for their work.

3.1 Peer-to-Pool vs. Peer-to-Peer

Most DePIN projects adopt a peer-to-pool model. In this model, the client makes a request to the network, and the network selects a provider to respond to the client's needs. More importantly, this means that the client pays the network, and the network pays the fee to the service provider.

Another option is the peer-to-peer model, in which clients request services directly from providers. This requires clients to be able to find a group of service providers and choose one to work with. At the same time, clients pay fees directly to providers.

Verification is even more important in the peer-to-pool model than in the peer-to-peer model. In the peer-to-peer model, although the provider or the customer may lie, because the customer pays the provider directly, both parties can discover the problem on their own without having to prove to the network that the other party lied and choose to stop the transaction. In the peer-to-pool model, the network needs a mechanism to adjudicate disputes between customers and providers. Typically, when a provider joins the network, they agree to serve any customer assigned by the network, so the only way to prevent or resolve disputes between customers and providers is to adopt some decentralized verification method.

The DePIN project chose a peer-to-pool design for two reasons. First, the peer-to-pool model makes it easier to provide subsidies by using native tokens. Second, it is able to optimize the user experience (UX) and reduce the off-chain infrastructure required to use the network. A similar example can be found outside of DePIN, namely the difference between peer-to-pool decentralized exchanges (DEXs, such as Uniswap) and peer-to-peer DEXs (such as 0x).

Tokens are important because they help solve the cold start problem when building a network. Whether it is Web2 or Web3, projects often provide strong value to users through some form of subsidy to build network effects. These subsidies are sometimes direct economic incentives (such as lower costs) and sometimes value-added services that cannot be scaled . Tokens often provide an economic subsidy while also helping to build a community and giving customers a say in the direction of the network.

The peer-to-pool model allows users to pay an amount of X, and the service provider receives a reward of Y, where X < Y. This is usually due to the native token created by the DePIN project, and the service provider is rewarded with this token. The token reward Y can be higher than the amount X paid by the customer because speculators buy the tokens and give them a market price higher than the initial value (when the network is not yet used, the initial value of the token is often very low or even zero).

The ultimate goal is: as service providers improve service efficiency, the DePIN project achieves X > Y by building network effects, thereby using the difference between X and Y as protocol revenue.

In contrast, the peer-to-peer model makes it more difficult to implement token rewards as subsidies. If the customer pays X and the service provider receives Y, where X < Y, and the customer and the provider can interact directly, then the provider may pretend to be a customer purchasing services from itself through "self-dealing". This behavior is difficult to avoid in the decentralized DePIN protocol unless some degree of centralization is introduced or a peer-to-pool model is adopted.

3.2 Self-Dealing

Self-dealing is when a user plays the role of both a customer and a service provider, attempting to extract value from the network by trading with themselves. This behavior is obviously harmful to the network, so most DePIN projects try to address this problem.

The simplest solution is to offer no subsidies or token incentives, but this would make it much harder to solve the network cold start problem.

Self-dealing is particularly harmful when the cost of providing services to the self-trader is zero (which is usually the case). One common way to solve self-dealing is to require service providers to stake tokens (usually native tokens) and distribute customer requests to service providers based on the staked weight.

Although staking can mitigate the self-dealing problem, it does not completely solve it. The reason is that large service providers (those who stake a large number of tokens) may still profit from a portion of the customer requests that are allocated to them. For example, if the service provider's reward is five times the cost of the customer's payment, then a service provider who stakes 25% of the tokens will receive a reward of five tokens for every four tokens spent.

This scenario assumes that the self-trader has zero cost to provide the service to itself and receives no benefit from requests assigned to other providers. If the self-trader can receive some benefit or value from requests assigned to other providers, then at a specific ratio of client cost to provider reward, the self-trader may extract more value.

3.3 Verification Method

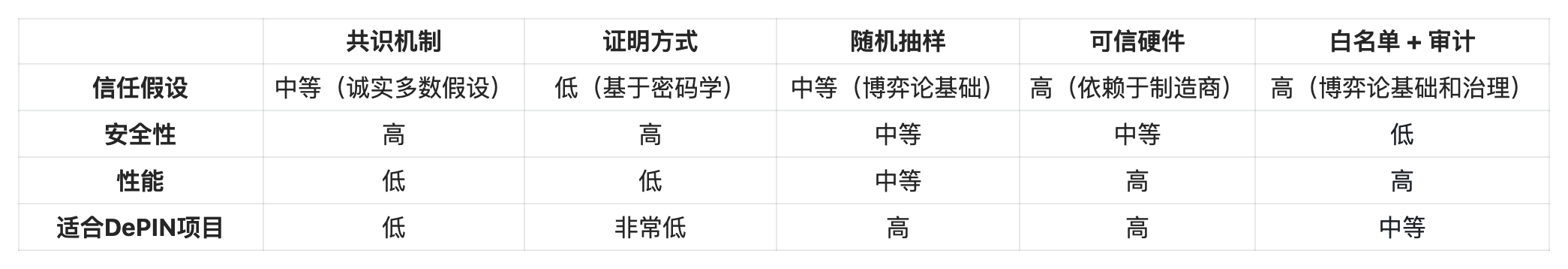

Now that we understand why authentication is a critical issue, let’s discuss different authentication mechanisms that can be considered for DePIN projects.

Consensus

Most blockchains use a consensus mechanism (usually combined with a Sybil-resistant mechanism such as Proof of Work (PoW) or Proof of Stake (PoS ). It may be more helpful to rephrase “consensus” as “re-execution”, as it highlights that each node in a blockchain network that forms a consensus must typically re-execute every computation processed by the network. (This rule does not fully apply to modular blockchains, or blockchain architectures that separate consensus, execution, and data availability.)

Re-executions are often necessary because every node in the network is often assumed to exhibit Byzantine behavior. In other words, nodes need to check each other's work because they cannot trust each other. When a new state change is proposed, every node validating the blockchain must execute that state change. This can result in a lot of re-executions! For example, as of this writing, there are over 6,000 nodes in the Ethereum network.

Re-execution is usually transparent unless the blockchain uses Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs, sometimes also called hardware or secure enclaves) or Fully Homomorphic Encryption . See below for more information on these two technologies.

Proof of Correct Execution (e.g., validity summary, ZEXE, etc.)

Rather than requiring every node in a blockchain network to re-execute every state change, a single node can execute a given state change and generate a proof that the node executed the state change correctly. This proof of correct execution is faster to verify than directly executing the computation (a property that makes the proof concise ). The most common forms of such proofs are SNARK (Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge) or STARK (Succinct Transparent Argument of Knowledge). SNARK and STARK are often extended to zero-knowledge proofs, which are proofs that are completed without revealing any information about the proven statement. Therefore, when used to compress computational proofs, the terms SNARK/STARK and zero-knowledge proofs (ZK Proofs) are often used interchangeably .

The most well-known type of blockchain based on proof of correct execution is probably Zero-Knowledge Rollup (ZKR). ZKR is a second-layer blockchain (L2) that inherits the security of an underlying blockchain. ZKR batches transactions, generates a proof that these transactions were executed correctly, and then publishes the proof to the first-layer blockchain (L1) for verification.

Proof of Correctness is often used to improve blockchain scalability and performance , privacy , or both. zkSync, Aztec, Aleo, and Ironfish are typical examples in this regard. In addition, Proof of Correctness can also be used in other scenarios. For example, Filecoin uses ZK-SNARKs in its Proof of Storage. In recent years, Proof of Correctness has begun to be applied to machine learning reasoning (ML inference ), training (ML training ), identity authentication and other fields.

Random sampling/statistical measurement

Another way to solve the verification problem in the DePIN project is to randomly sample service providers and measure whether they respond to customer requests correctly. Such "challenge requests" are usually distributed in proportion to the service provider's stakeweight in the network, which not only helps with verification but also alleviates the self-trading problem.

Since many DePIN projects offer high rewards for the availability of service providers (availability rewards are usually higher than rewards for serving customer requests), random sampling can ensure that service providers are actually available. The network will occasionally send challenge requests to service providers, and if the provider responds to the request correctly and the hash value of the request exceeds a certain difficulty threshold, the provider will receive a reward equivalent to the block reward. This mechanism can motivate rational service providers to respond to customer requests correctly because they cannot distinguish between ordinary customer requests and challenge requests.

Some version of random sampling is most widely used in DePin projects focused on network functionality, such as Nym , Orchid , and Helium .

Compared to consensus mechanisms, random sampling may have better scalability because the number of samples can be much smaller than the number of state changes in the network.

Trusted Hardware

Trusted hardware is not only useful for privacy protection (as mentioned above), but can also be used to verify sensor data. For the DePIN project, a major challenge of decentralized verification is the need to solve the oracle problem, that is, how to introduce data from the physical world into the blockchain in a trustless or minimally trusted way. Trusted hardware allows the network to adjudicate disputes between customers and service providers based on the results of physical sensor data.

Although trusted hardware often has vulnerabilities , it may be a pragmatic solution in the short to medium term, or as another layer of protection in deep defense. The most common Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) include Intel SGX , Intel TDX, and ARM TrustZone . Blockchain projects such as Oasis , Secret Network , and Phala all use TEEs, and the SAUVE project will also use TEEs.

Whitelisting and Auditing

The most pragmatic and least technically complex solution for verification is often to whitelist specific physical devices to participate in the DePIN protocol, while manually auditing logs and telemetry data to ensure that the service provider is correctly servicing the customer.

In practice, this typically involves building custom hardware with embedded signing keys and requiring that all hardware participating in the network must be purchased from a verified manufacturer. The manufacturer then whitelists a set of embedded keys. Only data signed with key pairs on the whitelist will be accepted by the network. This approach assumes that it is very difficult to extract the embedded keys from the device, and that the manufacturer can accurately report which keys are embedded in which devices. To address these challenges, manual audits are usually required.

To further ensure the correctness of the service, DePIN protocols typically elect an "auditor" through protocol governance, who is responsible for looking for malicious behavior and reporting its findings to the protocol. Auditors are human, and are therefore able to identify clever attacks that standardized protocols may not be able to detect, and once identified, these attacks may appear quite obvious to humans. Typically, auditors are authorized to submit potential penalties to protocol governance (such as slashing staked funds), or directly trigger slashing events. This approach also assumes that protocol governance will be guided by the best interests of the protocol, while also facing the human incentive challenges involved in any social consensus.

The best solution?

Faced with multiple potential authentication options, a new DePIN protocol often finds it difficult to decide on the best option.

Consensus mechanisms and proofs of correct execution are generally not feasible for verification. The DePIN protocol involves physical services, and consensus or proofs can only provide strong guarantees for computational (i.e. digital, not physical) state changes. To use consensus or proofs for verification in the DePIN protocol, an oracle must be introduced at the same time, which itself comes with a set of (usually weaker) trust assumptions.

Random sampling is a good fit for the DePIN protocol because it is efficient and in line with game theory logic, which can be well applied to physical services. Trusted hardware and whitelisting are usually the best choices for startup because they are the simplest and easiest to implement, but they are also the most centralized solutions and have a lower probability of success in the long run.

Why DePIN is important

While the popularity of cryptocurrencies stems from the desire to free control of money from the state, in reality, more essential services — like basic internet connectivity, electricity, and access to water — concentrate power in the hands of a few. By decentralizing these networks, we can create not only a freer society, but also a more efficient and prosperous one.

A decentralized future means that many people — not just the privileged few — can contribute to coming up with better solutions. This philosophy is rooted in the belief that potential human capital is everywhere. If you’re excited about decentralized financial systems or decentralized developer platforms, think further about the other essential web-based services we use every day.

About the Author

Guy Wuollet is a partner in the a16z crypto investment team, focusing on investing in all layers of the crypto stack. Prior to joining a16z, Guy worked with Protocol Labs on independent research, working on building decentralized network protocols and upgrading Internet infrastructure. He holds a bachelor's degree in computer science from Stanford University and was a key player on the school's rowing team.