When ETH continues to decline, and many users are shouting "Fix your eth" under Vitalik's tweets, people are curious about what Vitalik, the founder of Ethereum, is thinking?

ETH drops below $1,800 Source: Coingecko

On March 29, 2025, Vitalik published two blog posts that could reveal his current thoughts. Apparently, Vitalik is not particularly concerned about the ETH price.

Here are the two recent blog posts by Vitalik:

First, the Tree Ring Model of Culture and Politics

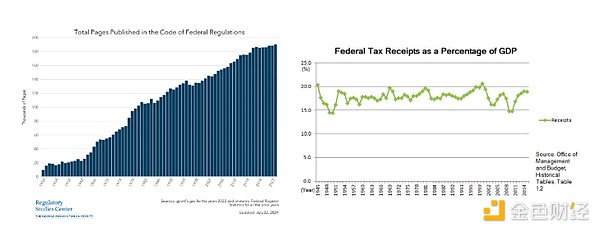

Throughout my growth, one thing that often confused me was people repeatedly claiming we live in a highly "deregulated" "deep neoliberal society". I was puzzled because while I saw many people advocating for neoliberalism and deregulation, the actual state of government regulation was very different from any regulation that would reflect these values. The total number of federal regulations has been continuously increasing. KYC, copyright, airport security, and various other rules are constantly tightening. Since World War II, the percentage of federal taxes to GDP in the United States has remained roughly the same.

If you told someone in 2020 that five years later, the United States or China would lead in open-source AI, with the other leading in closed-source AI, and asked them which would lead where, they would likely stare at you as if you were asking a tricky question. The United States is an open-minded country, China is a country that values closure and control, and US technology is generally more inclined towards open-source than Chinese technology, come on, this is obvious! However, they were completely wrong.

What's going on here? In this article, I will propose a simple explanation that I call the tree ring model of politics and culture:

The model is as follows:

How a culture treats new things is a product of the attitudes and incentive mechanisms prevalent in that culture during a specific period.

How a culture treats old things is mainly influenced by status quo bias.

Each period adds a new ring to the tree, and as the new ring forms, people's attitudes towards new things also take shape. However, these boundaries quickly become fixed and difficult to change, and a new ring begins to grow, influencing people's attitudes towards the next wave of topics.

We can analyze the above situation and others from the following perspectives:

The United States indeed has a trend of deregulation, but this trend was most apparent in the 1990s (if you look closely, you can actually see this from the chart!). By the 21st century, the tone had shifted towards increased regulation and control. However, if you look at the specific mature things from the 1990s (such as the internet), you'll find they ultimately became regulated, based on the principles dominant in the 1990s, which gave the United States (and most of the world due to imitation) decades of relative internet freedom.

Taxation is constrained by budget needs, which are primarily determined by the needs of medical and welfare programs. The "red line" in this area was set decades ago.

Both law and culture consider all medium-risk activities involving modern technology more suspicious than dangerous mountain climbing, because dangerous mountain climbing has an extremely high mortality rate. This can be explained by the fact that dangerous mountain climbing is something people have been doing for centuries, and attitudes become more resolute when general risk tolerance was much higher.

Social media matured in the 2010s, and culture and politics viewed it partly as part of the internet and partly as a unique thing. Therefore, the attitude towards restricting social media usually does not extend to early internet - although internet authoritarianism generally grew, we did not see particularly strong attempts to crack down on unauthorized file sharing.

Artificial intelligence matured in the 2020s, with the United States leading and China following closely, so adopting an "complementary commodification" strategy in AI serves China's interests. This intersects with the generally supportive attitude of developers towards open-source. The result is a very real environment for open-source AI, but also quite specific to AI; older technology fields remain closed, like walled gardens.

More generally, the implication is that it is difficult to change a culture's way of treating things that already exist and things whose attitudes have solidified. It is easier to invent new behavioral patterns that transcend old patterns and strive to maximize our chances of obtaining good norms. This can be achieved in various ways: developing new technologies is one, using physical or digital communities on the internet to experiment with new social norms is another. For me, this is also one of the attractions of the crypto space: it provides an independent technological and cultural foundation to do new things without being overly burdened by existing status quo bias. We can rejuvenate the forest by planting and cultivating new trees, rather than planting the same old trees.

Second, We Should Talk Less About Public Goods Funding and More About Open Source Funding

A topic I have long been concerned with is how to fund public goods. If a project provides value to a million people (and there is no fine-grained way to choose who can benefit and who cannot), but each person only receives a small part of the benefit, then it is likely that no one will feel that funding this project serves their interests, even if the project is overall very valuable. In economics, the term "public goods" has a century-long history. In digital ecosystems, especially decentralized digital ecosystems, public goods are extremely important: in fact, there is ample reason to suggest that the average commodity people might want to produce is a public good. Open-source software, academic research on crypto and blockchain protocols, openly available educational resources, and more are public goods.

However, the term "public goods" faces significant challenges.

[The translation continues in the same manner, maintaining the original structure and meaning while translating to English.]As an alternative to "public goods," let's consider the term "open source." If you think about some clear examples of digital public goods, you'll find that they are all open source:

Academic blockchain and cryptographic protocol research

Documentation, tutorials...

Open source software (such as Ethereum clients, software libraries...)

On the other hand, open source projects seem to be assumed as public goods. Of course, you can provide counterexamples: if I write software highly tailored to my personal workflow and put it on GitHub, most of the value created by the project may still belong to me personally. However, the act of open sourcing (rather than keeping it secret) is certainly a public good with widely distributed benefits.

A real advantage of the term "open source" is that it has a clear and widely recognized definition. The FSF's free software definition and OSI's open source definition have existed for decades, with natural ways to extend these definitions beyond software to other fields (such as writing, research). In the crypto space, the inherent state and multi-party nature of applications, and the new centralization vulnerabilities and control vectors implied by these factors, indeed mean we need to slightly expand the definition: open standards, internal attack testing, and exit testing introduced in this article can be valuable supplements to the FSF + OSI definition.

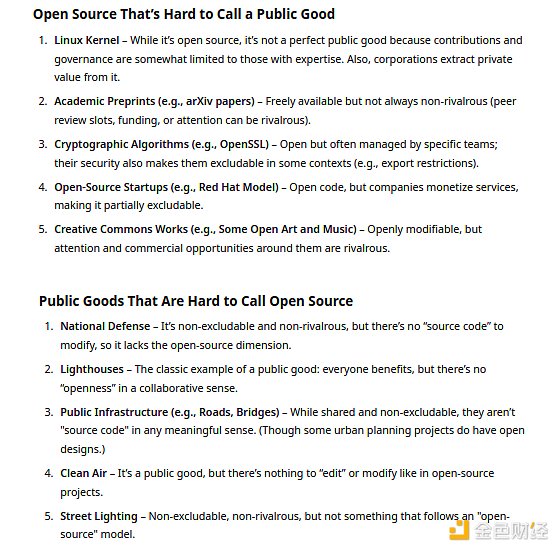

So what's the difference between "open source" and "public goods"? Well, let's have the robots give some examples:

I personally completely disagree with the claim that the first category of examples are not public goods. A project having a high contribution threshold does not prevent it from being a public good, nor does it prevent companies benefiting from the project. Moreover, a project can absolutely be a public good while things around it are private goods.

The second category is more interesting. First, we should note that these five examples are in physical space, not digital space. Therefore, if we want to focus on digital public goods, these examples provide no reason not to focus on "open source." But what if we really want to cover physical goods? Even the crypto space has its own enthusiasm for managing physical things, not just digital things; in a sense, this is the entire point of network states.

Open Source and Local Physical Public Goods

Here, we can make an observation: while providing these things locally is an "infrastructure construction" issue that can be done in open or closed source ways, the most effective way to provide these globally often ultimately involves... true open source. Clean air is the most obvious example: extensive research and development has been conducted, much of it open source, to help people around the world enjoy cleaner air. Open source can help make any type of public infrastructure easier to deploy globally. The question of how to effectively provide physical infrastructure locally remains important—but this issue equally applies to democratically managed communities and companies.

Defense is an interesting case. Here, I want to make the following argument: if you establish a project for defense reasons that you are unwilling to open source, it is very likely that while it may be a public interest locally, it may not be a public interest globally. Weapons innovation is the most obvious example. Sometimes one side in a war has a stronger moral justification than another, and helping them in offensive actions may be reasonable, but on average, developing technology to enhance military capabilities does not improve the world. Exceptions (defense projects people want to open source) might be "defensive" capabilities that are actually defensive; an example might be decentralized agricultural, power, and internet infrastructure that can help people maintain sustenance, normal operation, and stay connected in challenging environments.

Therefore, here, shifting focus from "public goods" to "open source" seems to be the best choice. Open source should not mean "just because it's open source, building anything is equally noble"; it should be about building and open sourcing what is most valuable to humanity. But distinguishing which projects are worth supporting and which are not is already the main task of public goods financing mechanisms, which is well known.