Author: YBB Capital Researcher Ac-Core

I. Ika Network Overview and Positioning

Image source: Ika

The Ika network, which receives strategic support from the Sui Foundation, has recently officially disclosed its technical positioning and development direction. As an innovative infrastructure based on Multi-Party Computation (MPC) technology, the network's most notable feature is its sub-second response speed, which is unprecedented in similar MPC solutions. Ika's technical compatibility with the Sui Blockchain is particularly outstanding, with both sharing highly aligned underlying design concepts in parallel processing and decentralized architecture. In the future, Ika will be directly integrated into the Sui development ecosystem, providing a plug-and-play cross-chain security module for Sui Move smart contracts.

From a functional perspective, Ika is building a new security verification layer: serving as a dedicated signature protocol for the Sui ecosystem while also providing standardized cross-chain solutions for the entire industry. Its layered design balances protocol flexibility and development convenience, with a certain probability of becoming an important practical case of large-scale MPC technology application in multi-chain scenarios.

[The rest of the translation follows the same professional and accurate approach]Fhenix: Based on TFHE, Fhenix has made several customized optimizations for the Ethereum EVM instruction set. It replaces plaintext registers with "encrypted virtual registers" and automatically inserts mini Bootstrapping before and after arithmetic instructions to restore noise budget. Meanwhile, Fhenix has designed an off-chain oracle bridging module that performs proof checks before interacting between on-chain encrypted states and off-chain plaintext data, reducing on-chain verification costs. Compared to Zama, Fhenix focuses more on EVM compatibility and seamless integration of on-chain contracts

2.2 TEE

Oasis Network: Building on Intel SGX, Oasis introduced the concept of a "layered trusted root" (Root of Trust), using SGX Quoting Service to verify hardware trustworthiness at the bottom layer, with a lightweight microkernel at the middle layer responsible for isolating suspicious instructions and reducing SGX enclave attack surfaces. The ParaTime interface uses Cap'n Proto binary serialization to ensure efficient cross-ParaTime communication. Additionally, Oasis developed a "durability log" module that writes key state changes to a trusted log to prevent rollback attacks.

2.3 ZKP

Aztec: Beyond Noir compilation, Aztec integrated "incremental recursion" technology in proof generation, recursively packaging multiple transaction proofs in chronological order and then generating a single small-sized SNARK. The proof generator is written in Rust with a parallelized depth-first search algorithm that can achieve linear acceleration on multi-core CPUs. Moreover, to reduce user waiting time, Aztec provides a "light node mode" where nodes only need to download and verify zkStream instead of complete Proof, further optimizing bandwidth.

2.4 MPC

Partisia Blockchain: Its MPC implementation is based on an extended SPDZ protocol, adding a "preprocessing module" that pre-generates Beaver triplets off-chain to accelerate the online computation phase. Nodes within each shard communicate via gRPC and interact through TLS 1.3 encrypted channels to ensure data transmission security. Partisia's parallel sharding mechanism also supports dynamic load balancing, adjusting shard sizes in real-time based on node load.

Three、Privacy Computing FHE, TEE, ZKPand MPC

Image source: @tpcventures

3.1 Overview of Different Privacy Computing Solutions

Privacy computing is currently a hot topic in blockchain and data security, with main technologies including Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE), Trusted Execution Environment (TEE), and Multi-Party Computation (MPC).

● Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE): An encryption scheme that allows arbitrary computation on encrypted data without decryption, achieving end-to-end encryption of input, computation process, and output. Secured by complex mathematical problems (such as lattice problems), it has theoretically complete computational capabilities but extremely high computational overhead. In recent years, the industry and academia have improved performance through algorithm optimization, specialized libraries (like Zama's TFHE-rs, Concrete), and hardware acceleration (Intel HEXL, FPGA/ASIC), but it remains a "slow but steady" technology.

● Trusted Execution Environment (TEE): A trusted hardware module provided by processors (such as Intel SGX, AMD SEV, ARM TrustZone), capable of running code in an isolated secure memory area, preventing external software and operating systems from viewing execution data and state. TEE relies on hardware trust roots, with performance close to native computing and generally minimal overhead. TEE can provide confidential execution for applications, but its security depends on hardware implementation and firmware provided by manufacturers, with potential backdoor and side-channel risks.

● Multi-Party Computation (MPC): Utilizing cryptographic protocols to allow multiple parties to jointly compute function outputs without revealing their private inputs. MPC has no single point of hardware trust but requires multi-party interaction, with high communication overhead limited by network latency and bandwidth. Compared to FHE, MPC has much lower computational overhead but higher implementation complexity, requiring carefully designed protocols and architectures.

● Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP): A cryptographic technique allowing verification of a statement without revealing additional information. The prover can prove to the verifier that they possess certain secret information (such as a password) without directly disclosing that information. Typical implementations include zk-SNARK based on elliptic curves and zk-STAR based on hashing.

3.2 Applicable Scenarios for FHE, TEE, ZKP, and MPC

Image source: biblicalscienceinstitute

Different privacy computing technologies have their own focuses, with the key being scenario requirements. Take cross-chain signatures, which require multi-party collaboration and avoiding single-point private key exposure - in this case, MPC is quite practical. Like threshold signatures, multiple nodes each hold a fragment of the key and complete the signature together, with no single node able to control the private key. Some more advanced solutions exist, such as Ika Network, which treats users as one party and system nodes as another, using 2PC-MPC parallel signatures that can process thousands of signatures at once and horizontally scale, becoming faster with more nodes. TEE can also complete cross-chain signatures by running signature logic through SGX chips, with fast speed and easy deployment, but the problem is that if the hardware is compromised, the private key will be exposed, with trust entirely dependent on the chip and manufacturer. FHE is weaker in this area because signature computation doesn't belong to its strengths of "addition and multiplication", and while theoretically possible, the overhead is so large that practically no one uses it in real systems.

In the DeFi scenario, such as multi-sig wallets, vault insurance, and institutional custody, multi-sig itself is secure, but the issue lies in how private keys are stored and signatures are risk-shared. MPC is currently the mainstream approach, with service providers like Fireblocks splitting signatures into multiple parts, with different nodes participating in signing, so that compromising any single node won't cause problems. Ika's design is also interesting, implementing "non-collusion" of private keys through a two-party model, reducing the traditional MPC possibility of "everyone agreeing to act maliciously". TEE also has applications in this area, such as hardware or cloud wallets using trusted execution environments to guarantee signature isolation, but still can't escape hardware trust issues. Currently, FHE has little direct use in custody layers, focusing more on protecting transaction details and contract logic, such as performing a private transaction where no one can see the amount and address, which has little to do with private key custody. In this scenario, MPC focuses on distributed trust, TEE emphasizes performance, and FHE is mainly used in higher-level privacy logic.

In AI and data privacy, the situation differs. FHE's advantages become more apparent here. It can keep data encrypted throughout the process, such as putting medical data on-chain for AI inference, with FHE allowing the model to complete judgments without seeing plaintext and then output results, with no one able to see the data clearly during the entire process. This "computing while encrypted" capability is particularly suitable for sensitive data processing, especially in cross-chain or cross-institutional collaboration. Projects like Mind Network are exploring having PoS nodes complete voting verification through FHE without knowing each other's status, preventing node cheating and ensuring process privacy. MPC can also be used for federated learning, with different institutions collaborating to train models while keeping local data unshared and only exchanging intermediate results. However, once multiple parties are involved, communication costs and synchronization become problematic, with such projects currently mostly experimental. While TEE can run models directly in a protected environment, with federated learning platforms using it for model aggregation, its limitations are obvious, such as memory restrictions and side-channel attacks. So in AI-related scenarios, FHE's "full-process encryption" capability is most prominent, with MPC and TEE serving as auxiliary tools but requiring specific solution coordination.

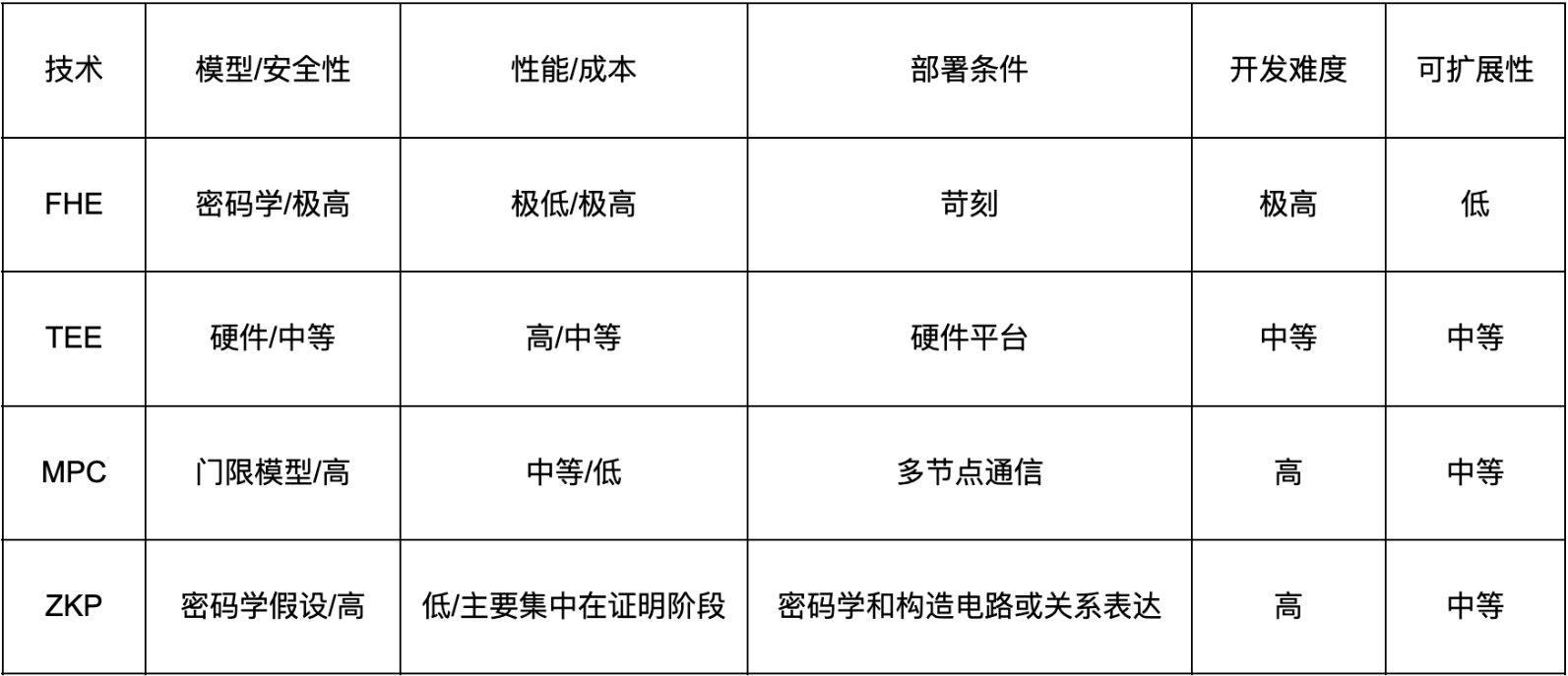

3.3 Differences Between Various Solutions

Performance and Latency: FHE (Zama/Fhenix) has higher latency due to frequent Bootstrapping but provides the strongest data protection in encrypted state; TEE (Oasis) has the lowest latency, close to normal execution, but requires hardware trust; ZKP (Aztec) has controllable batch proof latency, with single transaction latency between the two; MPC (Partisia) has medium-to-low latency, most affected by network communication.

Trust Assumption: FHE and ZKP are both based on mathematical hard problems, requiring no trust in third parties; TEE relies on hardware and manufacturers, with firmware vulnerability risks; MPC depends on semi-honest or at most t anomaly models, sensitive to the number and behavior of participants.

Scalability: ZKP Rollup (Aztec) and MPC sharding (Partisia) naturally support horizontal scaling; FHE and TEE scaling needs to consider computational resources and hardware node supply.

Integration Difficulty: TEE projects have the lowest access threshold, with minimal changes to programming models; ZKP and FHE both require specialized circuits and compilation processes; MPC needs protocol stack integration and cross-node communication.

IV. Market's General View: "FHE is Superior to TEE, ZKP, or MPC"?

It seems that whether FHE, TEE, ZKP, or MPC, all four face a Blockchain Trilemma in solving practical use cases: "performance, cost, security". Although FHE is attractive in theoretical privacy guarantees, it is not superior to TEE, MPC, or ZKP in all aspects. The cost of poor performance makes FHE difficult to popularize, with computational speed far behind other solutions. In applications sensitive to real-time performance and cost, TEE, MPC, or ZKP are often more feasible.

Trust and applicable scenarios also differ: TEE and MPC offer different trust models and deployment convenience, while ZKP focuses on verifying correctness. As industry perspectives point out, different privacy tools have their own advantages and limitations, with no "one-size-fits-all" optimal solution. For example, ZKP can efficiently solve off-chain complex computation verification; MPC is more direct for computing where multiple parties need to share private states; TEE provides mature support in mobile and cloud environments; while FHE is suitable for extremely sensitive data processing, but currently still requires hardware acceleration to be effective.

FHE is not "universally superior". The choice of technology should depend on application needs and performance trade-offs. Perhaps future privacy computing will often be the result of multiple complementary and integrated technologies, rather than a single solution winning out. For instance, Ika focuses on key sharing and signature coordination in its design (with users always retaining a private key), with its core value being decentralized asset control without custody. In comparison, ZKP excels at generating mathematical proofs for on-chain verification of states or computational results. They are not simple substitutes or competitors, but more like complementary technologies: ZKP can be used to verify cross-chain interaction correctness, thereby reducing trust requirements for bridge providers, while Ika's MPC network provides a underlying foundation for "asset control rights" that can be combined with ZKP to build more complex systems. Additionally, Nillion has begun integrating multiple privacy technologies to enhance overall capabilities, with its blind computing architecture seamlessly integrating MPC, FHE, TEE, and ZKP to balance security, cost, and performance. Therefore, the future privacy computing ecosystem will tend to use the most suitable technology component combinations to construct modular solutions.

Reference Contents:

(2)https://blog.sui.io/ika-dwallet-mpc-network-interoperability/