In 2010 , Google launched a second-price ad auction system, where the highest bidder wins the ad space but only has to pay the second-highest bid.

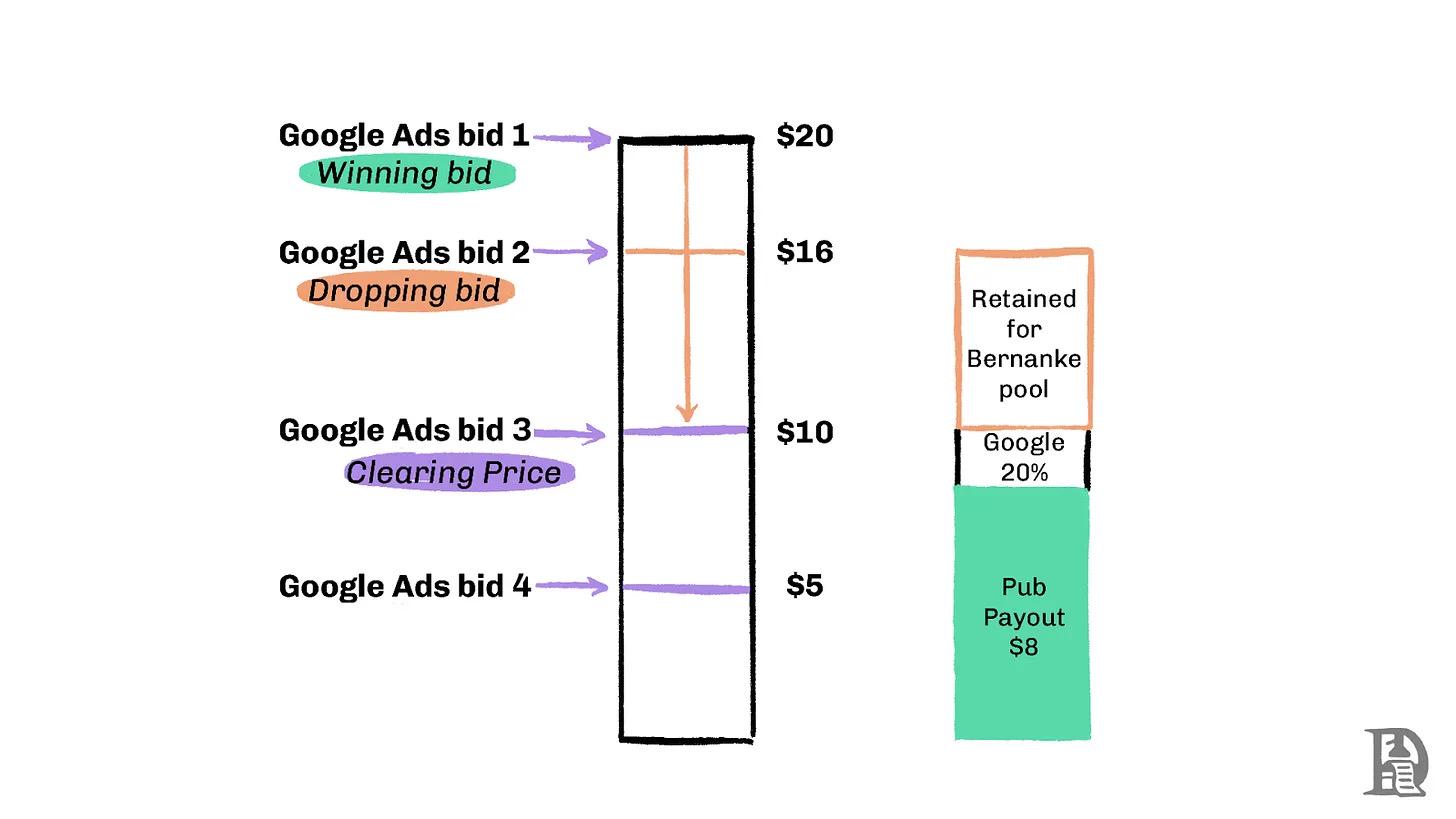

This looks like an ideal model for economists, which would help prevent advertisers from overbidding. However, behind the scenes, Google secretly made millions of dollars in hidden profits by manipulating the auction mechanism. For example, when the highest bid is $20 and the second highest bid is $16, the winning bidder only has to pay $16. However, Google actually pays the website publisher the third highest price (assuming $10), pocketing the $6 difference. The funds flowed into a secret account known as the " Bernanke Pool " and were used to meet corporate goals, including Wall Street expectations. This operation was not exposed until an antitrust lawsuit in 2016.

Although Google switched to a first-price auction system in 2019 (settling publishers based on the highest bid), the lesson remains profound: when the auctioneer controls the underlying rules, even the most perfect mechanism can be distorted.

Interestingly, this is happening again in the cryptocurrency world. Blockchain is facing its own “Bernanke moment” — the maximum extractable value (MEV, or the profit gained through reorganization, addition, and deletion of block transactions) has become the most critical yet least understood phenomenon in the cryptocurrency space. Just like Google’s hidden auction manipulation, this kind of value extraction is beyond the view of ordinary users, but it affects all blockchain participants and forms a kind of “hidden tax”.

Will MEV follow in Google's footsteps and become a shady and centralized system, or will it evolve into a transparent decentralized system that returns profits to users? Can we design a mechanism that allows value extraction to feed back into the ecosystem, rather than concentrating wealth in the hands of a few? Now, let’s take a deeper look.

The physics of delay

Blockchain is a decentralized network consisting of thousands of verification nodes (validators or miners) around the world. These nodes play a dual role : they are both communication hubs that receive and broadcast transactions, and computing terminals that execute and verify transactions.

Because nodes are distributed around the world, there is bound to be latency in communications between validators - a physical bottleneck dictated by the speed of light. To ensure that all nodes follow the same transaction order, each blockchain sets a "block time": a validator is selected through a consensus mechanism (such as proof of stake) to propose a new block, and the remaining validators accept the block after confirming that the transaction is compliant. After each block is generated, the proposal rights will rotate among the validators to maintain network security. For example, Bitcoin produces blocks every 10 minutes, Ethereum has increased the pace to 12 seconds, Solana is trying to break the 400 millisecond limit, and L2 such as Arbitrum is challenging the ultra-high frequency range of 10-250 milliseconds.

Regardless of length, each block time window creates an opportunity for validators to reorganize transactions for profit, rather than prioritizing user fairness. Ideally, the "first come, first served" principle should be followed, but due to the global distribution of nodes, this principle is difficult to achieve. When a user initiates a transaction, it is almost impossible for all nodes to receive the transaction synchronously due to network latency. This means that even if the block construction rules are fully complied with, unfair transaction ordering (causing users to pay additional fees and MEV arbitrageurs to intercept the difference) may still be included in the block.

MEV (Maximum Extractable Value) refers to the profit that block producers (miners in proof-of-work or validators in proof-of-stake) and other participants (who bribe block producers to put user transactions first) obtain by strategically adjusting the order of transactions within a block.

MEV: A hidden and lucrative business

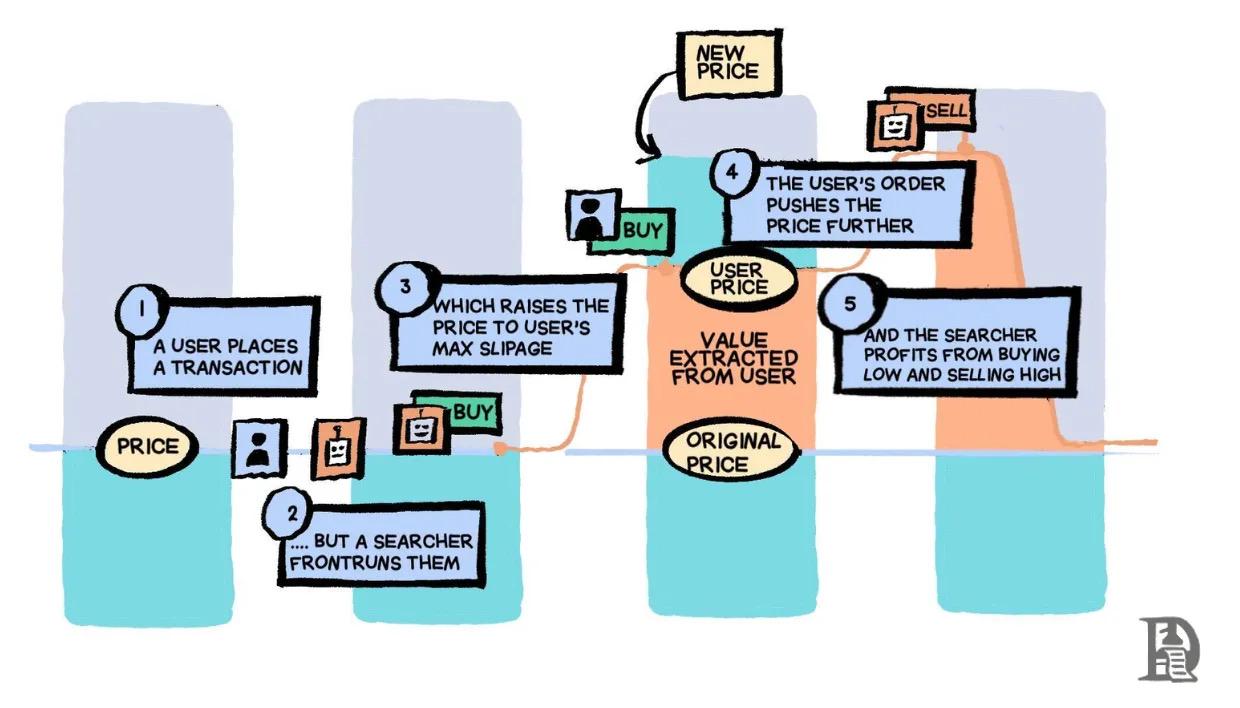

Let’s say Joel is using a DEX like Uniswap to buy ETH for $1,800. He sets his slippage tolerance at 10%, meaning he can accept a price increase to $1,980 by the time the trade is completed.

Joel’s transaction first goes to the mempool — a public waiting room for pending transactions, waiting to be included in a block. At this point, a trading robot discovered his transaction and immediately copied the order, "jumping the queue" by paying a higher gas fee (a higher gas fee is essentially a bribe to the validator to ensure that the transaction can be executed before Joel). When the robot’s buy order pushed the price of ETH on the DEX to $1,900, Joel’s transaction was ultimately executed at this inflated price. The robot then sells the ETH back to the funding pool at this price and earns the difference (after deducting the gas fee). In the end, although Joel bought ETH, he overpaid by $100, and the money went into the robot's pocket. Similar operations occur thousands of times every day in the cryptocurrency market.

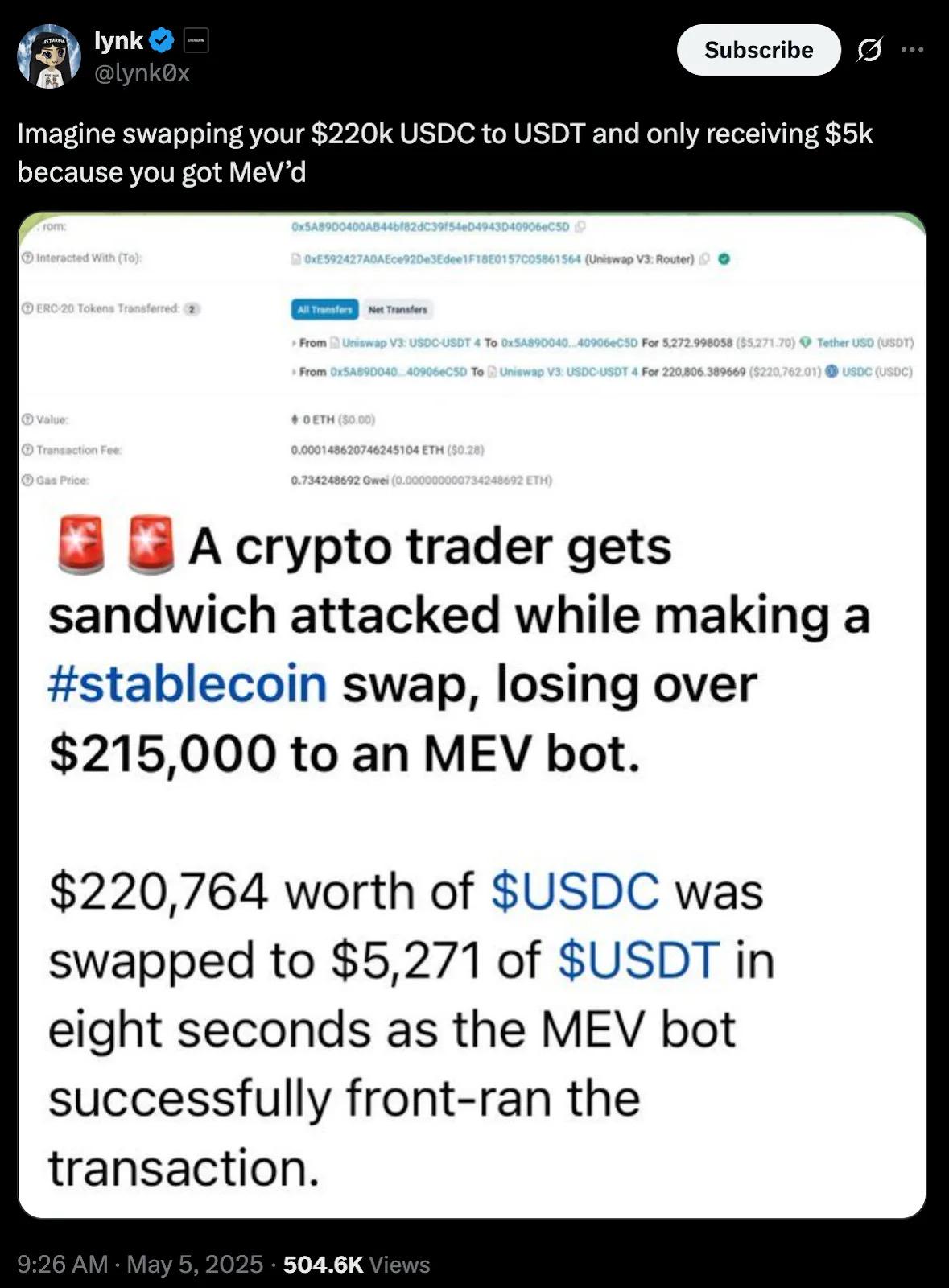

In a more extreme example, a robot captured $200,000 in profits on a single trade because a trader forgot to set a slippage tolerance. The "culprit" in this incident is jaredfromsubway.eth . This robot always completes the operation before the transaction it wants to snipe by continuously paying the highest gas fee in Ethereum. According to statistics, Jared made more than $10 million in profits through this type of MEV attack.

MEV is mainly manifested in three forms:

- Arbitrage trading: discover price differences between different exchanges and buy low and sell high within the same block. For example, when the price of ETH on Uniswap is $2,500 and that on Sushiswap is $2,510, the robot can complete the buying and selling operations in the same block, making a risk-free profit of $10 per ETH. It is important to note that this type of operation is actually beneficial to the market because it promotes price convergence across platforms.

- Sandwich attack: When the robot observes Alice’s large buy order in the memory pool, it buys first and pushes up the price, and then sells immediately after Alice completes the transaction at a high price. The robot earns the difference, while Alice suffers slippage loss. The case mentioned above where Joel paid an extra $100 is a typical sandwich attack. This additional expenditure was ultimately converted into profit for the MEV value chain. Such operations are obviously disadvantageous to users and cause them to pay unnecessary additional costs.

- Liquidation arbitrage: In a lending agreement, when a position reaches liquidation conditions, MEV extractors will compete to become the first liquidator to obtain rewards. For example, Saurabh borrowed 10,000 USDC with ETH worth $15,000 as collateral, and when the ETH price fell and the collateral value dropped to $11,000, liquidation was triggered. At this point, the robot will immediately repay the 5,000 USDC loan and receive ETH worth $5,500 (including a 10% liquidation reward), making an easy profit of $500. The impact of such operations is two-sided: from the perspective of maintaining the health of the DeFi system, a liquidation mechanism is necessary; but the vast majority of the profits are ultimately obtained by the validators.

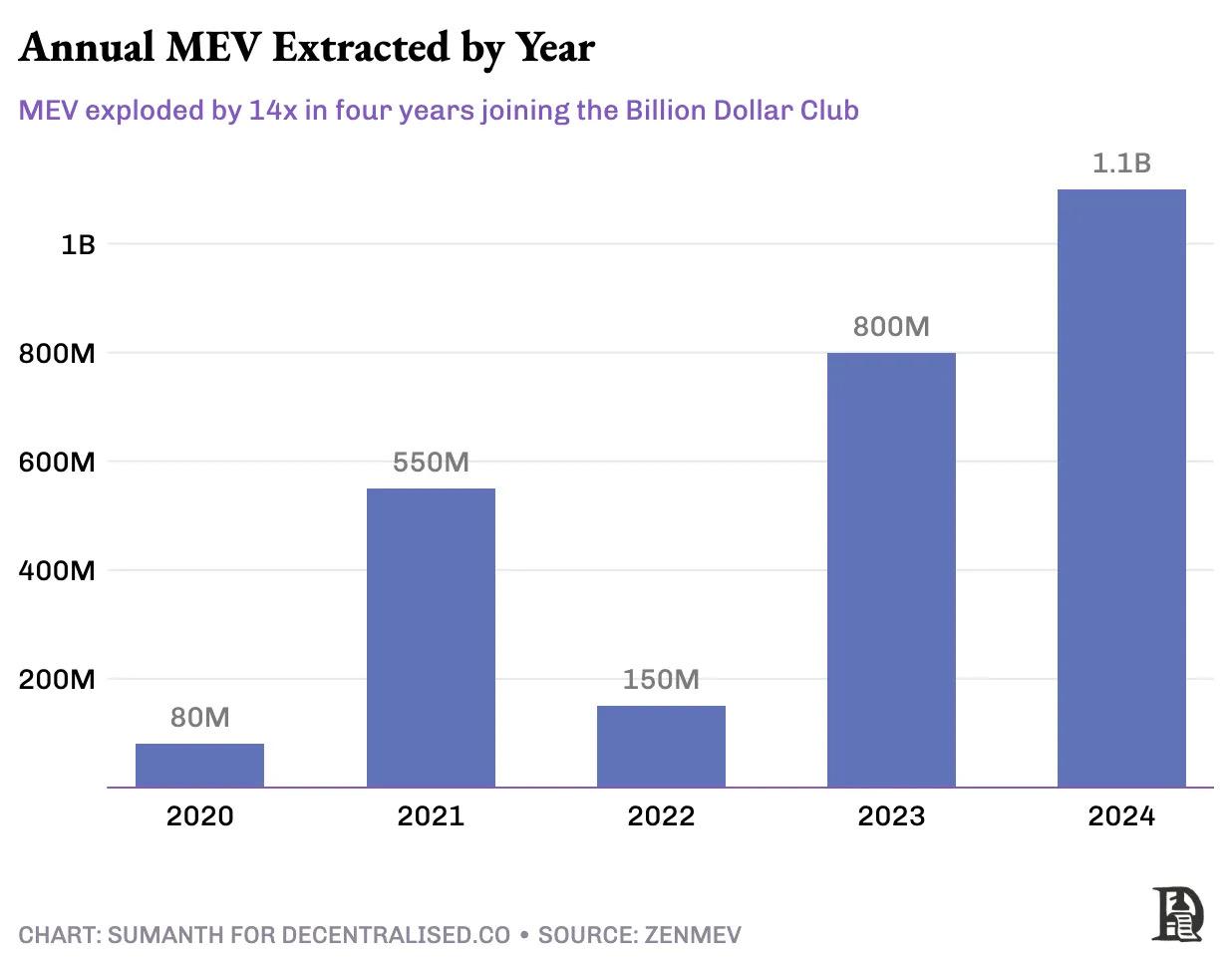

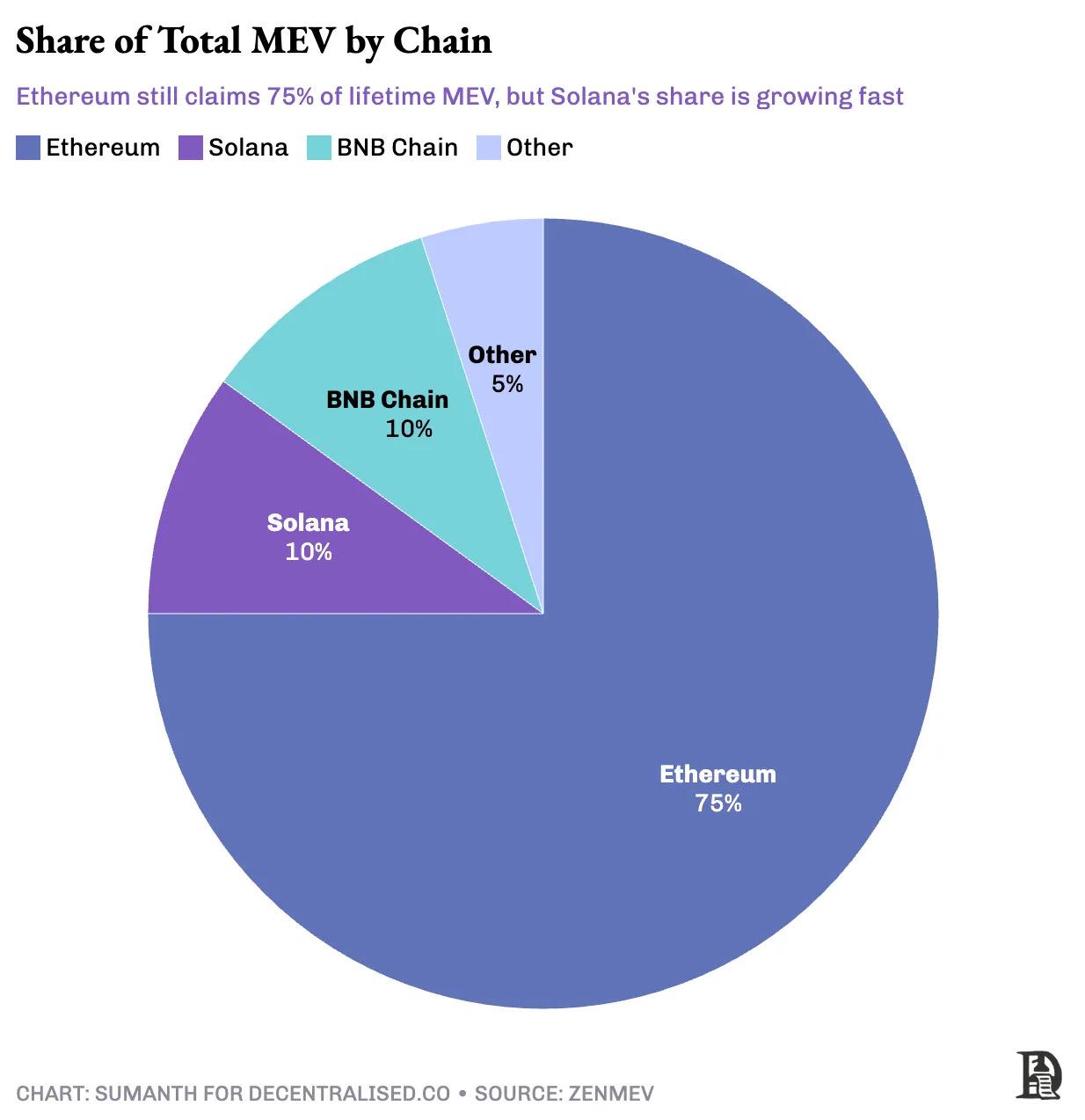

MEV extraction has doubled from $550 million in 2021 to $1.1 billion in 2024. And with its open memory pool and deep DeFi liquidity, Ethereum is still the main battlefield for MEV, with more than 100 active robots accounting for about 75% of MEV extraction activities. Data from the past 30 days shows that sandwich attacks accounted for 66% of Ethereum's total MEV, arbitrage transactions accounted for 33%, and liquidation arbitrage accounted for less than 1%.

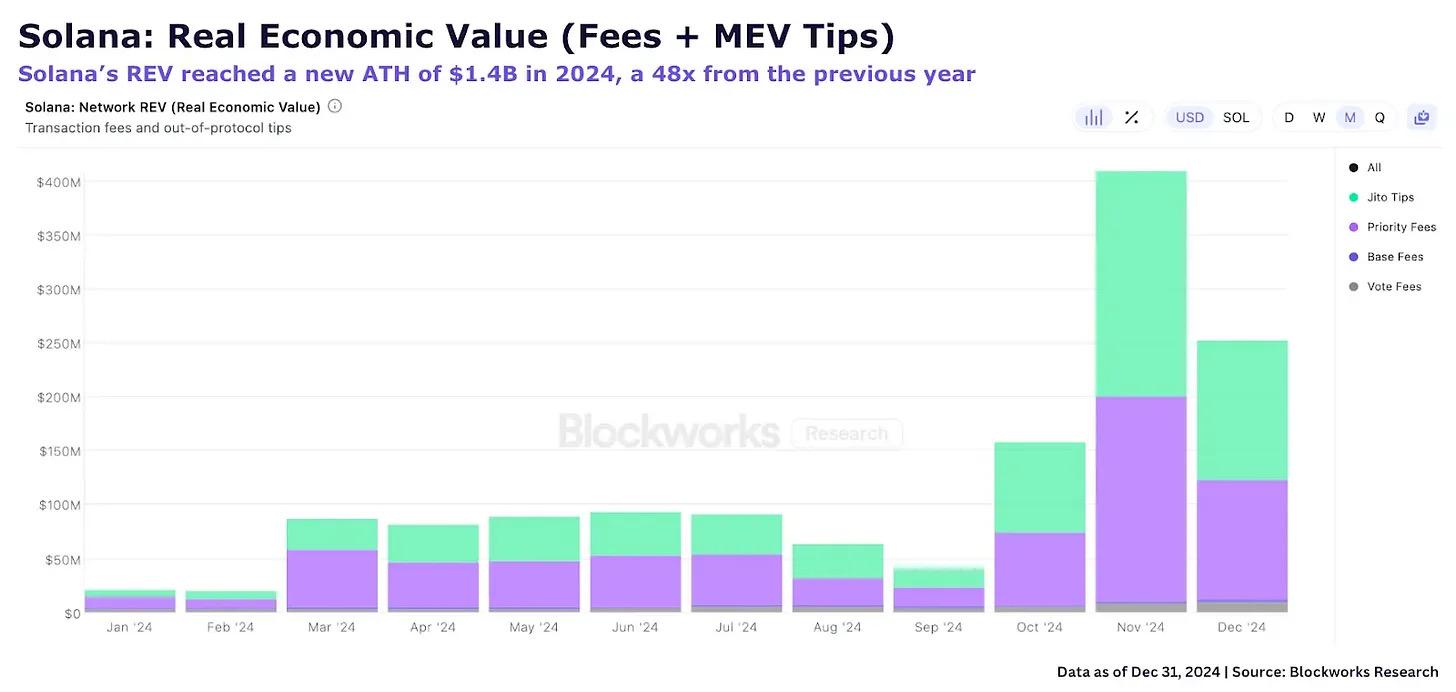

As on-chain transactions expand to other public chains, MEV also spreads. Solana, BNB Chain, and Ethereum Rollup networks have all become hunting grounds for arbitrage robots, and even CZ was hit by a sandwich attack when performing a token swap. In the past 30 days alone, the Sandwich robot on Solana has made a profit of more than 4 million US dollars ( 24,000 SOL ), which is 50 times the profit of similar robots on Ethereum in the same period ( $80,000 ).

In addition, the rise of cross-chain bridges has upgraded this game into a "chain relay race." Arbitrage bots began to rapidly switch between ecosystems, chasing every dollar of potential profit. In December 2024 alone, due to market fluctuations caused by Trump's re-election campaign, the scale of MEV activity on Solana exceeded the $100 million mark.

Last year, the total DEX transaction volume was approximately US$1.5 trillion. Based on this calculation, the MEV cost accounted for approximately 0.1% of the total transaction volume. However, research from Frontier Labs shows that for large transactions, this rate can be as high as 1%. While it’s easy to view MEV as a scourge, the reality is that value loss exists in all financial markets. The key question is: Can we reduce this loss? Or at least share these costs more equitably among market participants?

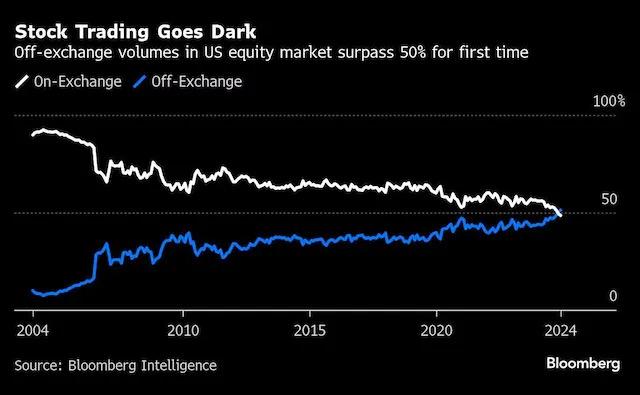

MEV Supply Chain

The two major privileges granted to validators by early blockchains (deciding which transactions can enter the next block and controlling the ordering of transactions) remind me of the "dark pool" problem in "Flash Boys" . Just as stock exchanges create privileged access for high-frequency traders, validators can secretly collude with bots to ensure that their trades are executed before those of ordinary users. This "pay-to-jump" mechanism means that insiders always get the best prices, while ordinary users can only get worse prices.

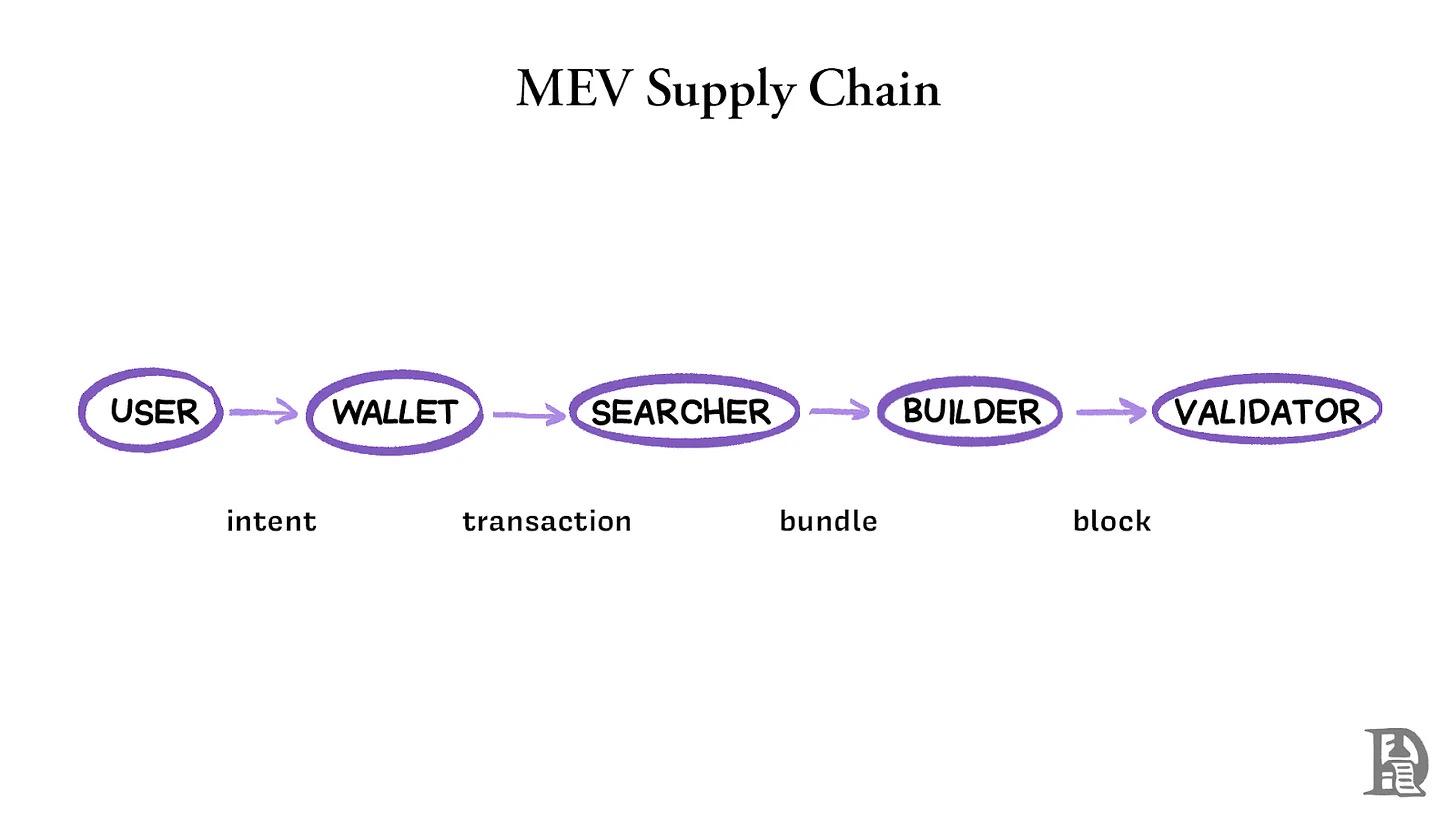

To resolve this centralization risk, the Ethereum ecosystem is turning to the "proposer-builder separation" ( PBS ) solution to separate the functions of block construction and chain upload:

- A user submits a transaction or high-level intent (e.g. “Exchange token A for token B at the best exchange rate”)

- After the wallet processes the transaction, it is sent to the searcher/builder/memory pool through the node

- Seekers scan memory pools for arbitrage opportunities and package related transactions

- Builders assemble transaction packages and hold block auctions

- The validator (proposer) selects the block with the highest profit and verifies the validity of all transactions before uploading them to the chain.

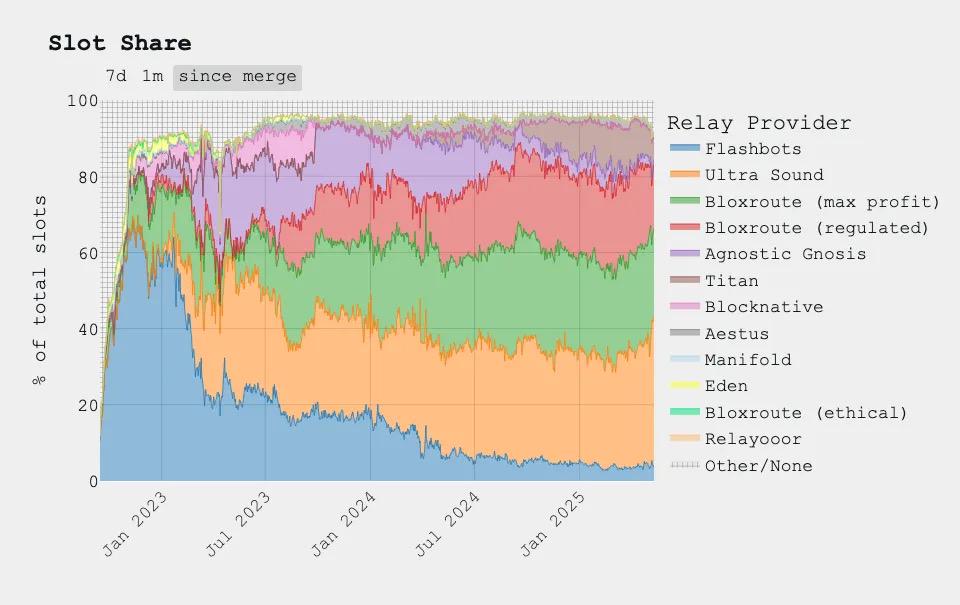

This separation of roles reduces the power of validators. They can now only choose from pre-sorted blocks, making MEV opportunities more widely distributed and creating a competitive block creation market. The most widely adopted PBS scheme at present is MEV-Boost developed by Flashbots, which has been adopted by more than 90% of Ethereum validators as of early 2025.

The evolution of terminology from "Miner Extractable Value" to "Maximum Extractable Value" indicates that the arbitrage subjects have expanded from miners to the entire ecological role. When you click “Exchange” on a DEX, whether you are using an automated market maker (AMM) like Uniswap or an order book model like Raydium, it is almost impossible for your counterparty to be another ordinary user. Professional market makers behind the scenes (such as Wintermute) earn the bid-ask spread by providing liquidity. In the AMM mechanism, they obtain transaction fees by injecting cryptocurrencies into the fund pool.

Trying to eliminate MEV is impractical as it is deeply embedded in block time economics. On the one hand, arbitrage behavior maintains price consistency between CEX and DEX, and even subsidizes network security through MEV tips; on the other hand, sandwich attacks and gas fee bidding wars force ordinary users to pay higher costs.

MEV is the inevitable product of an effective market. As long as there is profit margin, someone will grab it. The current ecosystem favors professional searchers, block builders, and market-making bots at the expense of regular traders who get front-runners, suffer additional slippage, or face liquidity being transferred to unauditable “dark pools.” Robots submit transactions to the memory pool at millisecond speeds to compete for MEV opportunities. This delay race not only clogs the mempoll with junk transactions and wastes bandwidth, but also pushes up transaction fees, becoming an invisible tax on every exchange. The key to the problem is not to eliminate MEV, but to decide who gets these benefits and on what terms.

Strategies to reduce MEV

To address the MEV problem, the industry has explored four main strategies : hiding, exploiting, minimizing, and redirecting. Each solution has different trade-offs between efficiency, fairness and technical complexity.

MEV hidden strategy

The simplest solution is to keep transaction information hidden until it is packaged. Tools like Flashbots Protect and Cowswap MEV Blocker are built for this purpose. Through these services, transactions are sent privately and directly to block builders rather than being publicly exposed in the memory pool. Arbitrage robots are not even aware of their presence until a trade is executed.

However, this strategy comes at the cost of having to wait for validators who adopt the service to be selected as proposers. Taking Flashbots Protect as an example, this process may take up to 6 minutes (however, since the transaction does not enter the public memory pool, the user can cancel the unexecuted transaction at any time). Market makers and large traders often use such services to avoid premature exposure of their trading strategies. To date, the transaction value processed through Flashbots Protect has exceeded US$43 billion.

I have reservations about these types of centralized privacy solutions because they always remind me of dark pool trading in traditional finance. Mechanisms initially designed to protect users often end up morphing into “Robinhood-style” insider privileges.

Flashbots and Beaverbuild are currently developing hardware solutions based on the Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) to prove their honesty through cryptography. This direction is promising, but has not yet been verified in large-scale practice.

In addition, some communities have begun to take proactive action. The BNB community voted to form the "Good Will Alliance" , requiring validators to only accept blocks submitted by builders that meet MEV specifications. These builders will filter out transactions that are exploitative of MEV, and the system will punish validators who do not adopt compliant infrastructure.

MEV Exploitation Strategy

Rather than eliminating MEV entirely, some protocols attempt to weaponize arbitrage competition through private auction mechanisms, allowing hunters to check and balance each other.

Consider a situation where Joel wants to convert 100 ETH into USDC. Under the traditional AMM model, this transaction will enter the public memory pool and be exposed to the risk of sandwich attacks. But in the RFQ mode, Joel sends a redemption request to the market maker network: suppose Wintermute quotes $2,000 per ETH and DWF Labs quotes $2,010. Joel will then accept the better offer and trade at $2010, completely avoiding the risk of slippage and front-running.

Behind the scenes, each market maker is calculating the potential profit on this trade. They provide the best quotes by mobilizing liquidity from multiple sources, while suppressing competitors while maintaining profits.

However, the RFQ system has inherent defects and requires a 24/7 online market maker network to respond instantly. If there are not enough participants, the system will appear sluggish and users may miss opportunities due to market fluctuations. RFQ is more used in areas with insufficient liquidity such as fixed income bonds. More importantly, if the market maker alliance lacks credibility or decentralization, RFQ may become a new insider club.

To this end, Pyth developed the off-chain market Express Relay on Solana, allowing all protocols to access a competitive market maker pool. DeFi applications can outsource trade execution and minimize MEV without having to connect to each market maker individually.

On the other hand, Jito chose another path and now controls more than 90% of Solana’s staked SOL. We previously reported that Jito attempted to build a memory pool on Solana, but gave up because the attacker spent $300,000 to buy block priority. Jito now holds off-chain auctions every 200 milliseconds to select the most profitable transactions and package them into the next block. Users purchase a fast track to MEV attack prevention by paying a “priority fee,” and these fees make up nearly half of Solana validators’ income.

MEV Minimization Strategy

This solution goes a step further than the order flow auction, radically reducing the total amount of MEV that can be withdrawn through clever auction design.

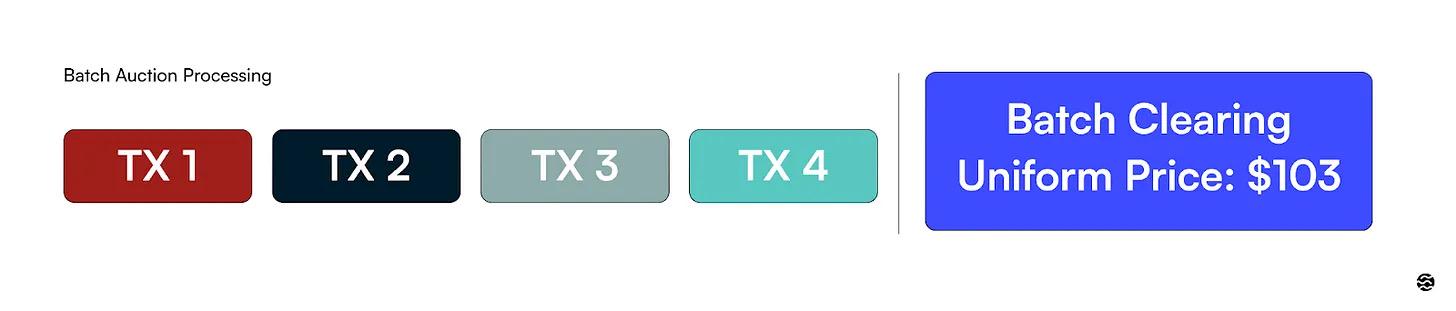

The traditional transaction-by-transaction processing model creates an opportunity for MEV - robots can observe each transaction and insert arbitrage operations. The batch trading agreement packages multiple orders together and executes them simultaneously at a unified price. Since all orders are grouped into the same batch and settled at the same price, the MEV robot cannot profit from sequencing or timing differences.

The batch trading mechanism pioneered by CoWSwap is based on a simple insight: when user A wants to exchange ETH for DAI, and user B wants to exchange DAI for ETH, the two parties can directly pair up and complete the transaction without going through an exchange. The protocol collects trading intentions within a short time window, prioritizes matching these natural hedging needs, and then uses on-chain liquidity to process remaining transactions.

Even better, traders don’t need to have an in-depth understanding of crypto market structure. When using CoWSwap, users do not have to adjust complex parameters such as slippage tolerance or cross-pool routing, they only need to declare their trading requirements. Solvers (professional market makers who act as auction settlers) compete to provide the best quotes, and all traders in the same batch enjoy the same asset price.

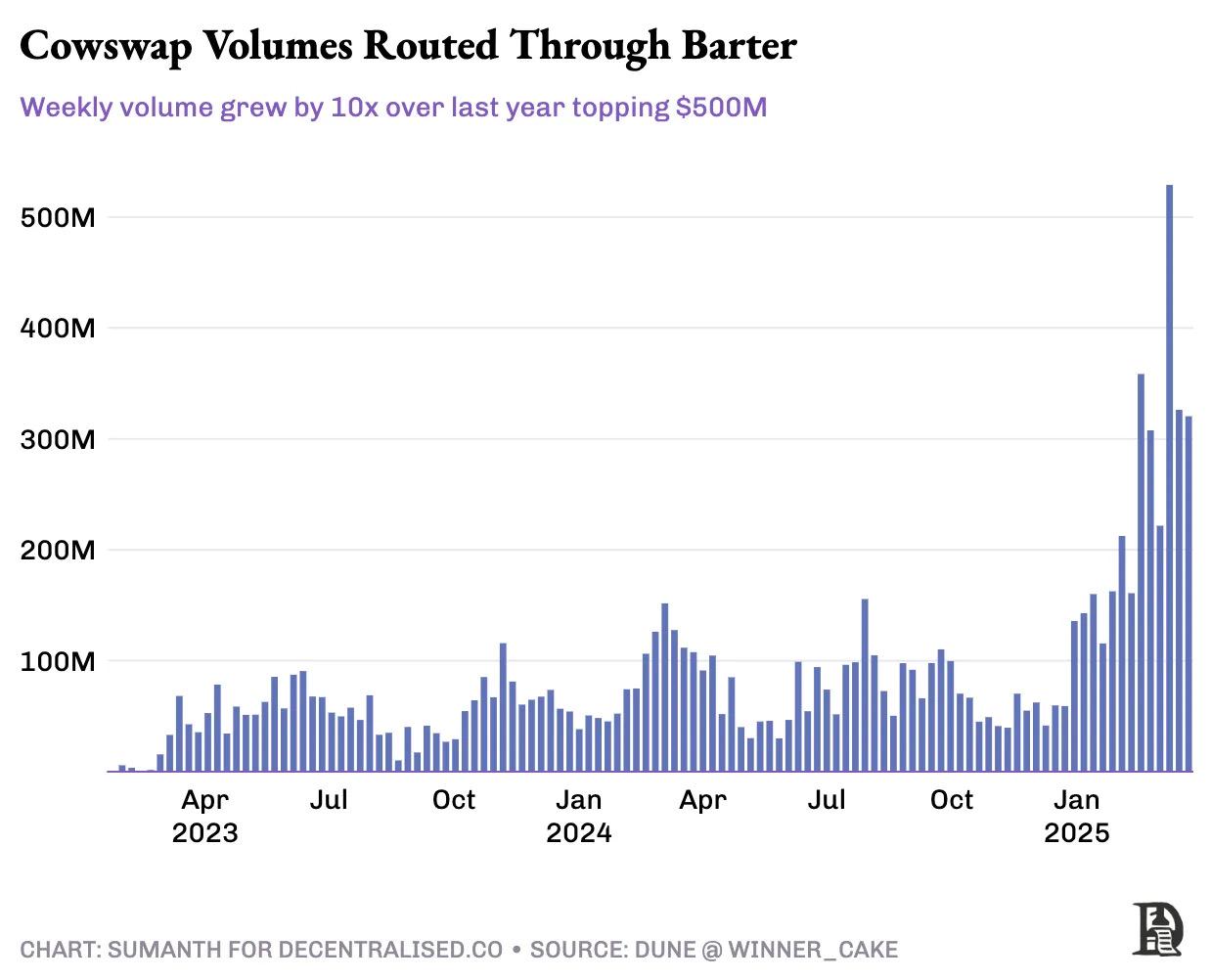

To date, CoWSwap has processed approximately $100 billion in transactions. Its leading solver Barter (market share of about 15%) has processed transactions exceeding US$11 billion through the protocol, and is showing a steady growth trend. This growth confirms the effectiveness of the batch auction mechanism in reducing MEV. The success of solvers such as Barter relies on price competition in a fair and unified execution environment, rather than transaction timing exploitation.

This mechanism coincides with the research of Professor Eric Budish of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He argues that large auctions once per second would eliminate the speed race in high-frequency trading: “Batching also solves the prisoner’s dilemma in continuous order book markets and distributes welfare gains to investors.”

In the cryptocurrency space, the traditional continuous order book model (such as used by most DEXs) rewards the fastest, causing traders to continuously invest in better hardware, faster bots, or more direct node connections, but these investments do not help improve the user experience. Batch auction logic like the one used by CoWSwap executes all transactions within a fixed time window at a uniform price, making the speed factor invalid and truly focusing on price discovery and user value.

MEV redirection strategy

Some innovators have taken a more pragmatic approach: if MEV extraction can’t be prevented, why not capture it and return the profits to the community?

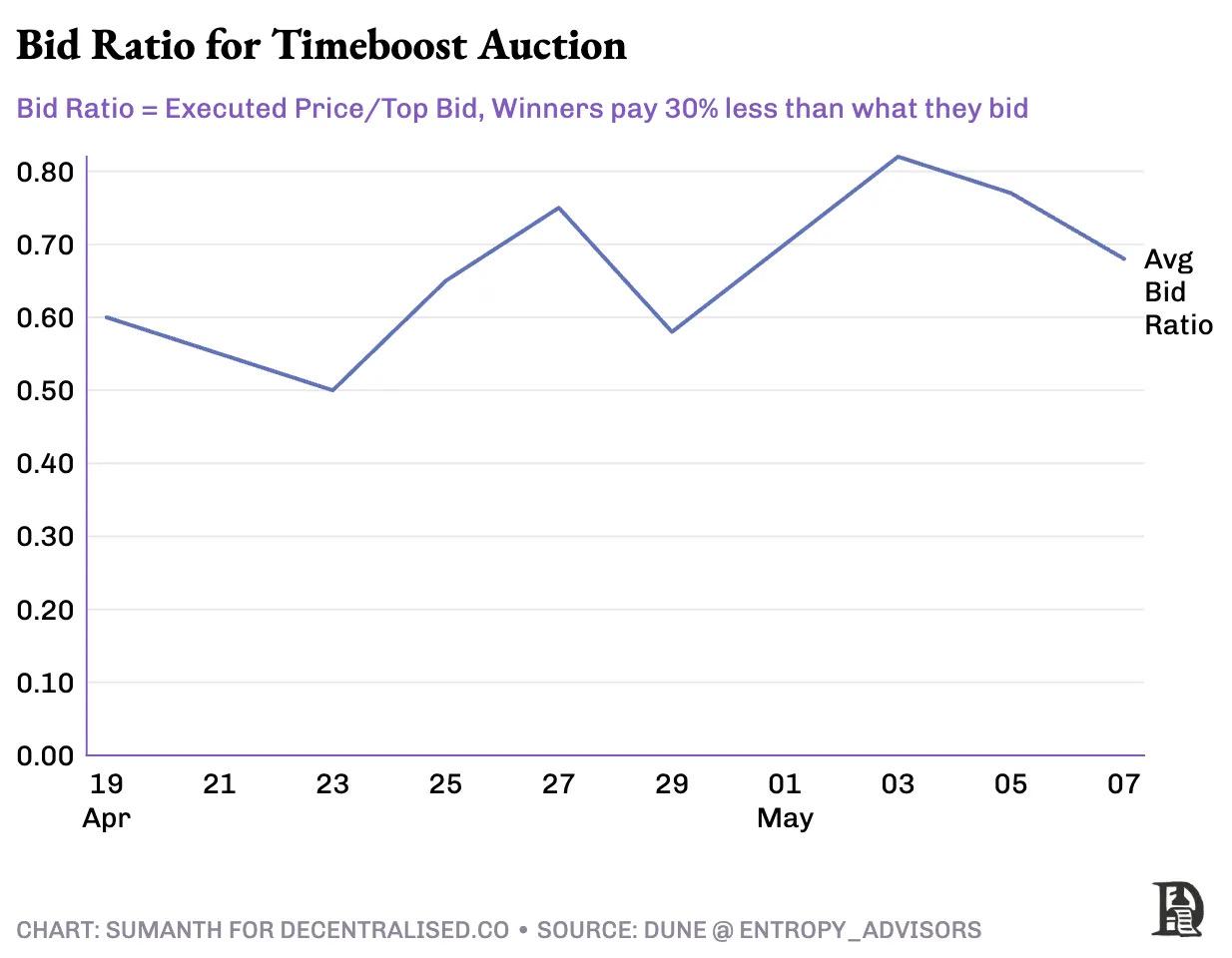

Arbitrum's TimeBoost is a perfect example of this concept. The protocol establishes a 200-millisecond "fast track" where usage rights are allocated every minute through a sealed-bid second-price auction. Just like the VIP checkout lanes at a supermarket, the highest bidder gets priority processing of transactions during a brief time window. Seekers who want their transactions to be prioritized can bid for this priority channel by predicting the MEV potential within the 60-second window without having to participate in a chaotic gas fee bidding war.

This mechanism completely changes the situation for attackers, who now miss the opportunity to profit from MEV from anyone using the fast lane. Since the auction rotates frequently among all searchers, it is almost impossible to form an extraction monopoly. The system transforms MEV from an implicit tax into a public good, with 97% of TimeBoost’s revenue going to the ARB DAO treasury, with an estimated annual revenue of $30 million.

In addition, Jito mentioned above also adopts a hybrid solution, where 3% of the transaction priority fee will be redistributed to Jito DAO and JitoSOL stakers.

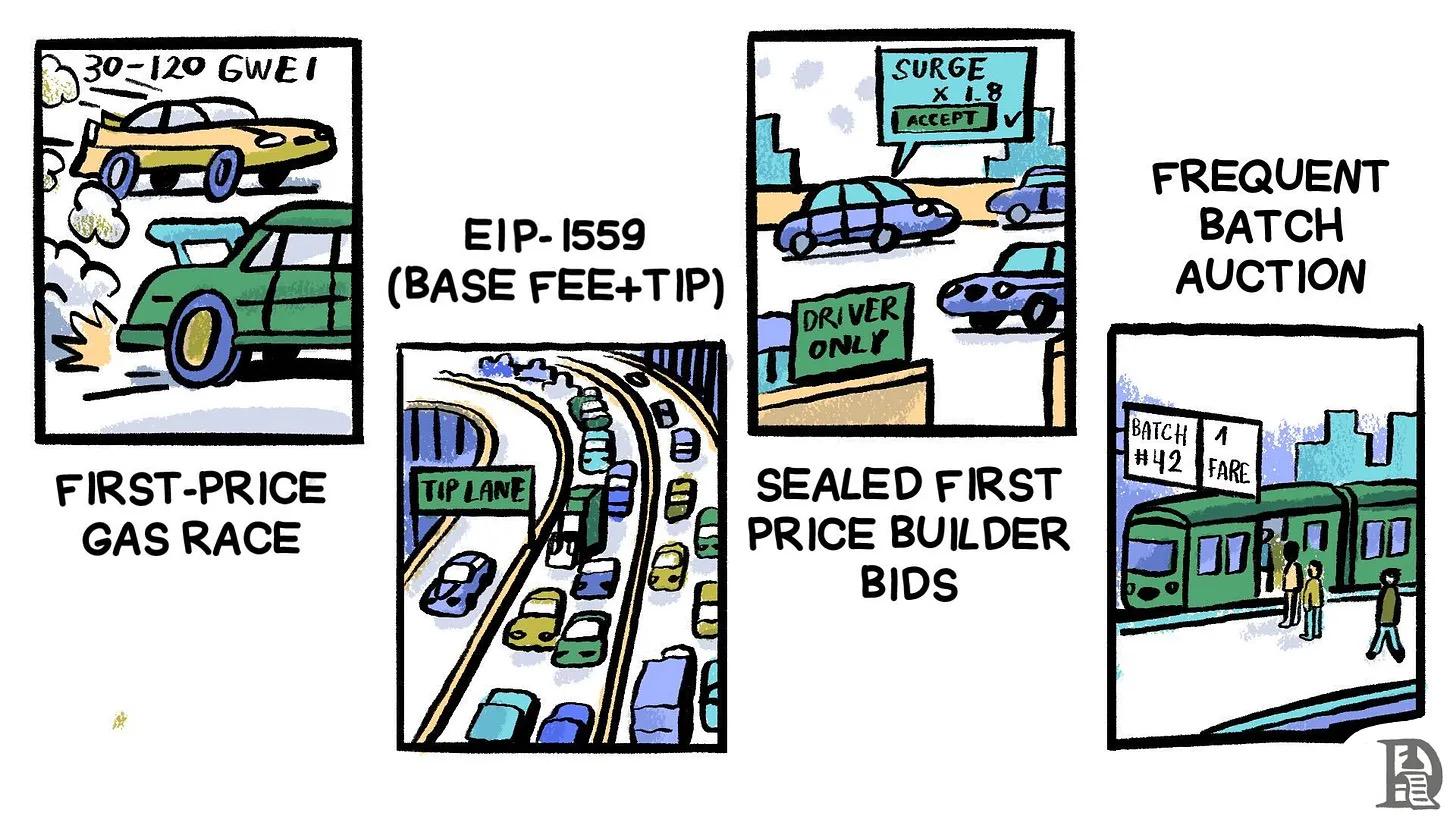

How to choose the MEV auction mechanism

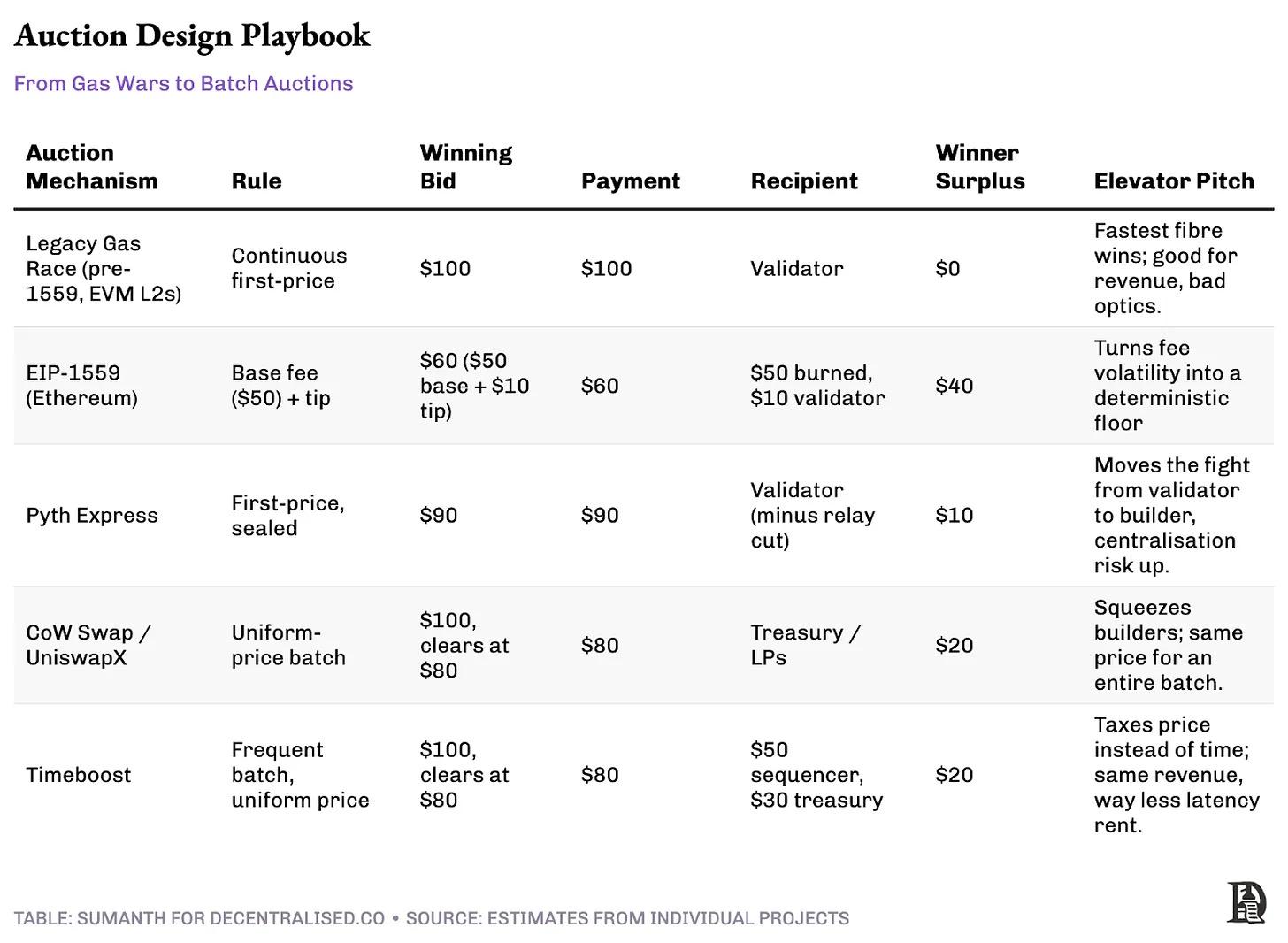

There are five core auction designs in the MEV field today. Let’s take the example of three participants (searchers/solvers/builders) bidding for block space, assuming that their respective private valuations are $100, $80, and $60 respectively.

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to the so-called "optimal" auction solution. The key depends on the goals of the agreement:

- Maximizing Revenue : Choose Sealed First-Price Auction

- Community credibility and user stickiness : Adopting a tiered mechanism similar to EIP-1559’s “base fee + intention unified price”

- Breaking the monopoly of MEV extraction : Implementing high-frequency batch auctions to let price, not speed, determine the outcome

- Speed-sensitive scenarios such as DEX : Private order flow is the best solution

The road ahead

The strategy of hiding order flow and auctioning it to private market makers sounds familiar, and the dark pool story on Wall Street is being repeated on the chain. This trend is likely to accelerate as cryptocurrencies become increasingly institutionalized and merge with traditional auction models.

Only the best teams are able to fulfill the roles of searchers, builders or solvers. This technological advantage will accumulate over time, giving large institutions with cutting-edge infrastructure and teams developing machine learning algorithms a structural advantage. Traditional market makers such as Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs may also join the battle.

At present, various chains have begun to express their positions on the MEV issue: Solana, which pursues ultra-low latency, tends to adopt a private order flow mechanism similar to Nasdaq's speed advantage; Ethereum uses PBS and MEV-Boost to achieve democratic access; and other public chains are exploring new directions based on their own architectural characteristics.

In my opinion, the most groundbreaking innovation may happen on Layer 2. As demonstrated by Arbitrum TimeBoost, L2 is freer to experiment with various auction designs and value distribution models.

The composable, permissionless nature of DeFi creates a mechanism iteration speed that far exceeds that of traditional markets. While high-frequency batch auctions have been discussed since 2015, they have been hampered by regulatory restrictions ; on-chain, projects like Sei can implement such innovations in just a few months. In addition, another solution is to establish a decentralized market maker network. In the future, a “builder reputation market” may emerge. Through systems such as Eigenlayer, market makers can prove their integrity by staking tokens, and protocols can be screened based on transparent reputation scores.

Please don't think these ideas are too idealistic. You should know that 20 years ago, no one believed that millisecond microwave towers would rebuild the trading order of the S&P 500. As long as interests exist, capital will find a way out.