Revisiting Secure DAS in One and Two Dimensions

Authors: Benedikt (@b-wagn), Francesco (@fradamt)

All code is available in a notebook.

I. Introduction

With the Fusaka upgrade, Ethereum will introduce a data availability sampling (DAS) mechanism called PeerDAS. The underlying data units, blobs, are extended horizontally with a Reed-Solomon code and arranged as rows of a matrix. The samples are then columns.

Columns are also the transmission unit on the network, and nothing smaller than a column can currently be exchanged. Due to this, two features are lacking in this initial version of PeerDAS:

- Partial reconstruction: being able to contribute to reconstruction by only reconstructing and re-seeding a part of the data, e.g., only one row (or a few rows) instead of the whole matrix.

- Full mempool compatibility: transactions come with blobs/rows and are often distributed ahead of time in the mempool. However, any single missing blob prevents a node from constructing columns, rendering all of the other mempool blobs useless.

To address these limitations, cell-level messaging has been strongly considered as a candidate for the next iteration of the protocol (see e.g., here). As this is also a key component of a two-dimensional DAS construction, this calls into question whether we should:

- Enhance 1D PeerDAS with cell-level messaging, or

- Transition to a 2D construction.

Or at least whether this transition would be a following iteration. In this post, we compare the efficiency of these two approaches under the assumption that both aim to provide the same level of security while minimizing bandwidth consumption.

Disclaimer: We will entirely ignore the security of the “cryptographic layer”, i.e., the security properties of KZG commitments that are used. This layer has been studied extensively here and here. Our focus are the statistical security properties related to the sampling process, treating the cryptographic layer as idealized.

Background: Data Availability Sampling

Let us begin by abstractly recalling the core idea behind data availability sampling (DAS).

In DAS, a proposer holds a piece of data and wants to distribute it across the network. Clients (which may be full nodes or validators) aim to verify that this data is indeed available without needing to download it in full.

To achieve this, the proposer extends the data using an erasure code. Each client then attempts to download kk random symbols of the resulting codeword and checks them against a succinct cryptographic commitment, which all clients download. In the DAS context, these symbols are also referred to as samples or queries. A client accepts the data (e.g., includes the corresponding block in their fork choice) only if all kk queries are successfully verified.

The high-level intuition behind the security of DAS (against a potentially malicious proposer) is:

- The cryptographic commitment guarantees that the proposer is committing to a valid codeword (see the notion of code-binding here);

- If enough clients accept, then their collective queries allow reconstruction of the full data, thanks to the properties of the erasure code.

This post focuses on the second point: How is reconstruction actually achieved? How many clients are enough? And how should we set the parameter kk?

We begin by addressing the first of these questions, explaining what we mean by partial reconstruction. Then, we shift our focus towards security.

Background: Partial Reconstruction

One of the central questions in DAS is: who can reconstruct the data, and when? Suppose we have an all-powerful “supernode” that can download enough samples from the network to reconstruct the entire data encoded via an erasure code. In such a case, if only a few code symbols are missing—perhaps withheld by a malicious proposer—this supernode can simply recompute the missing pieces and reintroduce them into the network (aka re-seeding). Eventually, these symbols propagate, and all clients accept.

This setup raises the concern of relying on such powerful supernodes, which may be a centralization factor. In fact, even if we use an erasure code with the minimal reconstruction threshold, a so-called MDS code such as Reed-Solomon, the supernode needs to download as much samples as the full original data before it can reconstruct.

This is where the concept of partial reconstruction enters the stage. We say that a code allows for partial reconstruction if small, local portions of the data can be recovered using significantly fewer samples than what’s needed for full reconstruction. Instead of needing a supernode to collect nearly all pieces, multiple smaller nodes can independently reconstruct parts of the data. In this way, partial reconstruction enables distributing the reconstruction task across many participants, reducing the reliance on centralized supernodes.

Besides enhancing the robustness of the network by reducing reliance on more powerful nodes, distributing the CPU load of reconstruction and the bandwidth load of re-seeding the reconstructed data can also be seen as a performance improvement. Currently, reconstruction is unlikely to help the data propagate in the critical path, which one might expect to be another benefit of employing erasure coding, because it takes ~100ms to reconstruct a single blob, with all proofs. By distributing this load across many nodes, each only responsible for one or a few blobs, the erasure coding can be useful for more than security guarantees.

Background: Subset Soundness

In this post, we want to compare different encoding schemes (1D vs 2D) with respect to their efficiency, under the assumption that they all achieve the same level of security. To make this comparison meaningful, we first need a clear understanding of what “security” entails in the DAS context.

The security notion we consider is known as subset soundness and considers an adaptive adversary. This notion is formally introduced as Definition 2 in the Foundations of DAS Paper, and it also underpins the security rationale of PeerDAS.

Intuitively, subset soundness models a powerful adversary who observes the queries made by a large set of nn clients/nodes. The adversary can then adaptively decide which symbols to reveal and which to withhold, effectively crafting the view each node sees. The adversary also selects a fraction of the nodes — say, \epsilon n \leq nϵn≤n for some fixed \epsilon > 0ϵ>0 — and aims to fool them into believing that the data is fully available. Notably, this choice can depend on the queries that the nodes made. We then consider the probability pp that the adversary wins this game, i.e., that

- the \epsilon nϵn nodes all accept, and

- the data is not fully available; that is: one cannot reconstruct it from their queries.

For our purposes, we want pp to be at most 2^{-30}2−30 (for any adversary). Below, we will set the number of queries kk per node depending on nn, \epsilonϵ, and the encoding scheme, such that p \leq 2^{-30}p≤2−30 is guaranteed.

Impact and Choice of \epsilonϵ:

The security notion described above is parameterized by \epsilon \in (0, 1]ϵ∈(0,1], which models the fraction of nodes the adversary attempts to fool. From the formal definition and a simple cryptographic reduction, it follows that subset soundness for a given \epsilonϵ (with fixed nn) implies subset soundness for any larger \epsilon' \geq \epsilonϵ′≥ϵ. In other words: if an adversary cannot fool an \epsilonϵ-fraction of nodes, then it certainly cannot fool a larger fraction \epsilon'ϵ′.But how does this relate to the overall consensus protocol? Suppose we know that an adversary cannot fool more than an \epsilonϵ-fraction of nodes. Each fooled node effectively behaves as an additional malicious node in the consensus process. Thus, when data availability sampling is used, the adversary gains up to an extra \epsilonϵ fraction of apparent malicious nodes.

For example, if consensus without DAS tolerates up to <{1}/{3}<1/3 malicious nodes, then with DAS in place, the system can now tolerate only up to <{1}/{3} - \epsilon<1/3−ϵ malicious nodes.

Therefore, in practice, we must choose \epsilonϵ to be small, say, \epsilon = 1\%ϵ=1%, to ensure the adversary’s influence remains negligible.

II. PeerDAS - the 1D Construction

In this section, we explain how PeerDAS works, which will be included in the Fusaka upgrade. We also explain how cell-level messaging enables partial reconstruction.

How it works

We describe how to encode data and how clients make their queries, ignoring everything related to the “cryptographic layer”, e.g., commitments and openings.

A blob is a set of mm cells, where each cell holds ff field elements. In the current parameter settings of PeerDAS, we have f = 64f=64 field elements per cell, and m = 64m=64 cells per blob. To consider various cell sizes, we let fm = 4096fm=4096 be constant (i.e., fix the data size), and vary f \in \{64,32,16,8\}f∈{64,32,16,8}, setting m = 4096 / fm=4096/f.

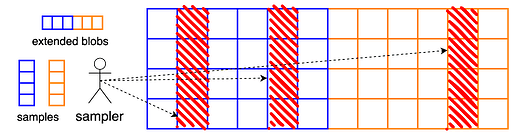

To encode a single blob, one extends the blob using a Reed-Solomon code of rate 1/21/2, resulting in 2m2m cells, or equivalently, 2fm = 81922fm=8192 field elements. In PeerDAS, we apply this encoding process to bb blobs independently and view the extended blobs as rows in a b \times 2mb×2m matrix of cells.

Clients now query entire columns of this matrix, i.e., they attempt to download bb cells at once. This means that the “symbols” or our erasure code are columns of the extended blob matrix. From any mm of these columns, one can reconstruct the entire matrix and therefore the data.

The concrete networking infrastructure supporting the sampling functionality are GossipSub topics for columns, i.e., sub-networks where only nodes interested in a specific sample (= column) participate.

Partial reconstruction

As anticipated, the current PeerDAS design does not support partial reconstruction. However, even such a one-dimensional encoding can in principle support this feature, when applied independently to many blobs, as it is in PeerDAS. In fact, by working with vertical units smaller than columns, such as cells, it is certainly possible to reconstruct only parts of the full matrix, for example individual rows or groups of rows. This presents two challenges:

- Partial re-seeding: when a node reconstruct a single row, it does not reconstruct any full sample (column), but it still needs to be able to contribute the reconstructed data back to the network.

- Obtaining enough cells to reconstruct: when only sampling columns, ability to reconstruct is all or nothing, i.e., either a node obtains enough columns to reconstruct the whole matrix, or cannot reconstruct any part of it. In other words, only supernodes can participate in reconstruction. We would like nodes to be able to do so while still only downloading a fraction of the whole data.

There are well known ways to approach them, which together give us partial reconstruction:

- Cell-level messaging: enable nodes to exchange cells rather than full columns, so that a node that reconstructs a row can re-seed it cell-by-cell, at least in the column topics that they participate in.

- Row topics: have nodes also attempt to download some rows, by participating in row topics, also equipped with cell-level messaging. Crucially, this is not sampling, and there are no security implications to how many rows are obtained, so even participating in a single row topic suffices. In fact, sampling rows is pointless in a 1D construction, since there is no vertical redundancy. The purpose of a row topic is only that cells from column topics can flow into it and enable row-wise reconstruction, without any supernode. The reconstructed cells can then flow from the row topic into all of the column topics, again without any single node needing to participate in all of them.

Note: the lack of vertical redundancy means that we need every row topic to successfully perform its reconstruction duties. If even a single row topic fails to do so (for example because of a network-level attack limited to the topic), the whole reconstruction cannot complete.

Number of samples

Let us now determine the number of samples kk per client for PeerDAS. As discussed above, we want to choose kk such that the probability pp that an adversary breaks subset soundness is at most 2^{-30}2−30.

The security of PeerDAS has been analyzed extensively here and here. The latter work builds on the security framework from here, and a concrete bound for subset soundness can be derived by combining Lemma 1 and Lemma 3 here. Ultimately, all of this yields the same bound for subset soundness, namely:

p \leq \binom{n}{n\epsilon}\cdot \binom{2m}{m-1} \cdot (\frac{m-1}{2m})^{kn\epsilon} \leq \binom{n}{n\epsilon}\cdot \binom{2m}{m-1} \cdot 2^{-kn\epsilon}.p≤(nnϵ)⋅(2mm−1)⋅(m−12m)knϵ≤(nnϵ)⋅(2mm−1)⋅2−knϵ.

Intuitively, the first binomial accounts for the ability of the adversary to freely and adaptively pick n\epsilonnϵ nodes to fool, the second binomial accounts for the adversary choosing m-1m−1 symbols to make available to these nodes, and the final term is the probability that all of their samples end up in this available portion of the encoding.

If we want that p \leq 2^{-30}p≤2−30 and n,m,\epsilonn,m,ϵ are given, we need to set

k \geq \frac{1}{n\epsilon} \left( \log_2 \binom{n}{n\epsilon} + \log_2 \binom{2m}{m-1} + 30 \right)k≥1nϵ(log2(nnϵ)+log2(2mm−1)+30).

Here is the code for computing kk:

from math import comb, log2, ceil # used laterfrom tabulate import tabulate # used laterimport numpy as np # used laterimport matplotlib.pyplot as plt # used laterdef min_samples_per_node(n: int, m: int, r: int = 2, eps: float = 0.01):"""Finds the smallest integer k such that k samples per nodeachieve security of 30 bits for the 1D construction.Inputs:n: total number of nodesm: number of symbols in original datar: inverse coding rate (total symbols = r*m), default=2eps: fraction of nodes to be fooled (0 < eps <= 1), default=0.01Returns:Smallest integer k satisfying the bound"""neps = int(n * eps)binom_n = comb(n, neps)binom_m = comb(m*r, m-1)log2_binom = log2(binom_n) + log2(binom_m)k = -(log2_binom + 30)/(n*eps*log2(1/r))return ceil(k)Columns are also the transmission unit on the network, and nothing smaller than a column can currently be exchanged. Due to this, two features are lacking in this initial version of PeerDAS:

- Partial reconstruction: being able to contribute to reconstruction by only reconstructing and re-seeding a part of the data, e.g., only one row (or a few rows) instead of the whole matrix.

- Full mempool compatibility: transactions come with blobs/rows and are often distributed ahead of time in the mempool. However, any single missing blob prevents a node from constructing columns, rendering all of the other mempool blobs useless.

To address these limitations, cell-level messaging has been strongly considered as a candidate for the next iteration of the protocol (see e.g., here). As this is also a key component of a two-dimensional DAS construction, this calls into question whether we should:

- Enhance 1D PeerDAS with cell-level messaging, or

- Transition to a 2D construction.

Or at least whether this transition would be a following iteration. In this post, we compare the efficiency of these two approaches under the assumption that both aim to provide the same level of security while minimizing bandwidth consumption.

Disclaimer: We will entirely ignore the security of the “cryptographic layer”, i.e., the security properties of KZG commitments that are used. This layer has been studied extensively here and here. Our focus are the statistical security properties related to the sampling process, treating the cryptographic layer as idealized.

Background: Data Availability Sampling

Let us begin by abstractly recalling the core idea behind data availability sampling (DAS).

In DAS, a proposer holds a piece of data and wants to distribute it across the network. Clients (which may be full nodes or validators) aim to verify that this data is indeed available without needing to download it in full.

To achieve this, the proposer extends the data using an erasure code. Each client then attempts to download kk random symbols of the resulting codeword and checks them against a succinct cryptographic commitment, which all clients download. In the DAS context, these symbols are also referred to as samples or queries. A client accepts the data (e.g., includes the corresponding block in their fork choice) only if all kk queries are successfully verified.

The high-level intuition behind the security of DAS (against a potentially malicious proposer) is:

- The cryptographic commitment guarantees that the proposer is committing to a valid codeword (see the notion of code-binding here);

- If enough clients accept, then their collective queries allow reconstruction of the full data, thanks to the properties of the erasure code.

This post focuses on the second point: How is reconstruction actually achieved? How many clients are enough? And how should we set the parameter kk?

We begin by addressing the first of these questions, explaining what we mean by partial reconstruction. Then, we shift our focus towards security.

Background: Partial Reconstruction

One of the central questions in DAS is: who can reconstruct the data, and when? Suppose we have an all-powerful “supernode” that can download enough samples from the network to reconstruct the entire data encoded via an erasure code. In such a case, if only a few code symbols are missing—perhaps withheld by a malicious proposer—this supernode can simply recompute the missing pieces and reintroduce them into the network (aka re-seeding). Eventually, these symbols propagate, and all clients accept.

This setup raises the concern of relying on such powerful supernodes, which may be a centralization factor. In fact, even if we use an erasure code with the minimal reconstruction threshold, a so-called MDS code such as Reed-Solomon, the supernode needs to download as much samples as the full original data before it can reconstruct.

This is where the concept of partial reconstruction enters the stage. We say that a code allows for partial reconstruction if small, local portions of the data can be recovered using significantly fewer samples than what’s needed for full reconstruction. Instead of needing a supernode to collect nearly all pieces, multiple smaller nodes can independently reconstruct parts of the data. In this way, partial reconstruction enables distributing the reconstruction task across many participants, reducing the reliance on centralized supernodes.

Besides enhancing the robustness of the network by reducing reliance on more powerful nodes, distributing the CPU load of reconstruction and the bandwidth load of re-seeding the reconstructed data can also be seen as a performance improvement. Currently, reconstruction is unlikely to help the data propagate in the critical path, which one might expect to be another benefit of employing erasure coding, because it takes ~100ms to reconstruct a single blob, with all proofs. By distributing this load across many nodes, each only responsible for one or a few blobs, the erasure coding can be useful for more than security guarantees.

Background: Subset Soundness

In this post, we want to compare different encoding schemes (1D vs 2D) with respect to their efficiency, under the assumption that they all achieve the same level of security. To make this comparison meaningful, we first need a clear understanding of what “security” entails in the DAS context.

The security notion we consider is known as subset soundness and considers an adaptive adversary. This notion is formally introduced as Definition 2 in the Foundations of DAS Paper, and it also underpins the security rationale of PeerDAS.

Intuitively, subset soundness models a powerful adversary who observes the queries made by a large set of nn clients/nodes. The adversary can then adaptively decide which symbols to reveal and which to withhold, effectively crafting the view each node sees. The adversary also selects a fraction of the nodes — say, \epsilon n \leq nϵn≤n for some fixed \epsilon > 0ϵ>0 — and aims to fool them into believing that the data is fully available. Notably, this choice can depend on the queries that the nodes made. We then consider the probability pp that the adversary wins this game, i.e., that

- the \epsilon nϵn nodes all accept, and

- the data is not fully available; that is: one cannot reconstruct it from their queries.

For our purposes, we want pp to be at most 2^{-30}2−30 (for any adversary). Below, we will set the number of queries kk per node depending on nn, \epsilonϵ, and the encoding scheme, such that p \leq 2^{-30}p≤2−30 is guaranteed.

Impact and Choice of \epsilonϵ:

The security notion described above is parameterized by \epsilon \in (0, 1]ϵ∈(0,1], which models the fraction of nodes the adversary attempts to fool. From the formal definition and a simple cryptographic reduction, it follows that subset soundness for a given \epsilonϵ (with fixed nn) implies subset soundness for any larger \epsilon' \geq \epsilonϵ′≥ϵ. In other words: if an adversary cannot fool an \epsilonϵ-fraction of nodes, then it certainly cannot fool a larger fraction \epsilon'ϵ′.But how does this relate to the overall consensus protocol? Suppose we know that an adversary cannot fool more than an \epsilonϵ-fraction of nodes. Each fooled node effectively behaves as an additional malicious node in the consensus process. Thus, when data availability sampling is used, the adversary gains up to an extra \epsilonϵ fraction of apparent malicious nodes.

For example, if consensus without DAS tolerates up to <{1}/{3}<1/3 malicious nodes, then with DAS in place, the system can now tolerate only up to <{1}/{3} - \epsilon<1/3−ϵ malicious nodes.

Therefore, in practice, we must choose \epsilonϵ to be small, say, \epsilon = 1\%ϵ=1%, to ensure the adversary’s influence remains negligible.

II. PeerDAS - the 1D Construction

In this section, we explain how PeerDAS works, which will be included in the Fusaka upgrade. We also explain how cell-level messaging enables partial reconstruction.

How it works

We describe how to encode data and how clients make their queries, ignoring everything related to the “cryptographic layer”, e.g., commitments and openings.

A blob is a set of mm cells, where each cell holds ff field elements. In the current parameter settings of PeerDAS, we have f = 64f=64 field elements per cell, and m = 64m=64 cells per blob. To consider various cell sizes, we let fm = 4096fm=4096 be constant (i.e., fix the data size), and vary f \in \{64,32,16,8\}f∈{64,32,16,8}, setting m = 4096 / fm=4096/f.

To encode a single blob, one extends the blob using a Reed-Solomon code of rate 1/21/2, resulting in 2m2m cells, or equivalently, 2fm = 81922fm=8192 field elements. In PeerDAS, we apply this encoding process to bb blobs independently and view the extended blobs as rows in a b \times 2mb×2m matrix of cells.

Clients now query entire columns of this matrix, i.e., they attempt to download bb cells at once. This means that the “symbols” or our erasure code are columns of the extended blob matrix. From any mm of these columns, one can reconstruct the entire matrix and therefore the data.

The concrete networking infrastructure supporting the sampling functionality are GossipSub topics for columns, i.e., sub-networks where only nodes interested in a specific sample (= column) participate.

Partial reconstruction

As anticipated, the current PeerDAS design does not support partial reconstruction. However, even such a one-dimensional encoding can in principle support this feature, when applied independently to many blobs, as it is in PeerDAS. In fact, by working with vertical units smaller than columns, such as cells, it is certainly possible to reconstruct only parts of the full matrix, for example individual rows or groups of rows. This presents two challenges:

- Partial re-seeding: when a node reconstruct a single row, it does not reconstruct any full sample (column), but it still needs to be able to contribute the reconstructed data back to the network.

- Obtaining enough cells to reconstruct: when only sampling columns, ability to reconstruct is all or nothing, i.e., either a node obtains enough columns to reconstruct the whole matrix, or cannot reconstruct any part of it. In other words, only supernodes can participate in reconstruction. We would like nodes to be able to do so while still only downloading a fraction of the whole data.

There are well known ways to approach them, which together give us partial reconstruction:

- Cell-level messaging: enable nodes to exchange cells rather than full columns, so that a node that reconstructs a row can re-seed it cell-by-cell, at least in the column topics that they participate in.

- Row topics: have nodes also attempt to download some rows, by participating in row topics, also equipped with cell-level messaging. Crucially, this is not sampling, and there are no security implications to how many rows are obtained, so even participating in a single row topic suffices. In fact, sampling rows is pointless in a 1D construction, since there is no vertical redundancy. The purpose of a row topic is only that cells from column topics can flow into it and enable row-wise reconstruction, without any supernode. The reconstructed cells can then flow from the row topic into all of the column topics, again without any single node needing to participate in all of them.

Note: the lack of vertical redundancy means that we need every row topic to successfully perform its reconstruction duties. If even a single row topic fails to do so (for example because of a network-level attack limited to the topic), the whole reconstruction cannot complete.

Number of samples

Let us now determine the number of samples kk per client for PeerDAS. As discussed above, we want to choose kk such that the probability pp that an adversary breaks subset soundness is at most 2^{-30}2−30.

The security of PeerDAS has been analyzed extensively here and here. The latter work builds on the security framework from here, and a concrete bound for subset soundness can be derived by combining Lemma 1 and Lemma 3 here. Ultimately, all of this yields the same bound for subset soundness, namely:

p \leq \binom{n}{n\epsilon}\cdot \binom{2m}{m-1} \cdot (\frac{m-1}{2m})^{kn\epsilon} \leq \binom{n}{n\epsilon}\cdot \binom{2m}{m-1} \cdot 2^{-kn\epsilon}.p≤(nnϵ)⋅(2mm−1)⋅(m−12m)knϵ≤(nnϵ)⋅(2mm−1)⋅2−knϵ.

Intuitively, the first binomial accounts for the ability of the adversary to freely and adaptively pick n\epsilonnϵ nodes to fool, the second binomial accounts for the adversary choosing m-1m−1 symbols to make available to these nodes, and the final term is the probability that all of their samples end up in this available portion of the encoding.

If we want that p \leq 2^{-30}p≤2−30 and n,m,\epsilonn,m,ϵ are given, we need to set

k \geq \frac{1}{n\epsilon} \left( \log_2 \binom{n}{n\epsilon} + \log_2 \binom{2m}{m-1} + 30 \right)k≥1nϵ(log2(nnϵ)+log2(2mm−1)+30).

Here is the code for computing kk:

from math import comb, log2, ceil # used laterfrom tabulate import tabulate # used laterimport numpy as np # used laterimport matplotlib.pyplot as plt # used laterdef min_samples_per_node(n: int, m: int, r: int = 2, eps: float = 0.01):"""Finds the smallest integer k such that k samples per nodeachieve security of 30 bits for the 1D construction.Inputs:n: total number of nodesm: number of symbols in original datar: inverse coding rate (total symbols = r*m), default=2eps: fraction of nodes to be fooled (0 < eps <= 1), default=0.01Returns:Smallest integer k satisfying the bound"""neps = int(n * eps)binom_n = comb(n, neps)binom_m = comb(m*r, m-1)log2_binom = log2(binom_n) + log2(binom_m)k = -(log2_binom + 30)/(n*eps*log2(1/r))return ceil(k)III. The 2D Construction

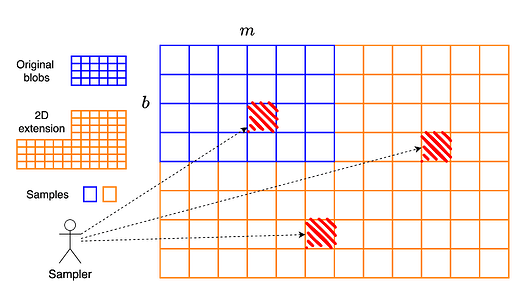

An alternative to PeerDAS is the two-dimensional construction, which has already been discussed (here and here and here). This construction is based on a tensor code of the Reed-Solomon code, and has been analyzed here, Section 8. It supports a natural form of partial reconstrution.

How it works

We can think of PeerDAS as extending a b \times mb×m matrix (bb blobs with mm cells per blob) horizontally into a b \times 2mb×2m matrix of cells. Equivalently, this is a b \times 2mfb×2mf matrix of field elements, where each cell contains ff field elements. Since the extension occurs only along the horizontal axis, PeerDAS is referred to as a one-dimensional construction.

In the two-dimensional construction, we proceed as follows: starting from the b \times 2mfb×2mf matrix that is derived as in PeerDAS, we then extend each column vertically using another Reed–Solomon code of rate 1/21/2. This results in a final matrix of size 2b \times 2mf2b×2mf, or equivalently, a 2b \times 2m2b×2m matrix of cells.

A key distinction from PeerDAS is that in the two-dimensional construction, clients sample individual cells, not entire columns. That is, a symbol of the code is a single cell, not a full column.

Partial reconstruction

Reconstruction in the two-dimensional construction is naturally a process that involves several sub-processes:

- As soon as at least mm cells are available within the same row, that row can be fully reconstructed.

- Similarly, as soon as at least bb cells are available within the same column, that column can be reconstructed.

This locality implies that there is no need for a central supernode to reconstruct the entire dataset. Instead, it suffices to have enough nodes that can independently reconstruct specific rows or columns, achieving the same goal in a decentralized manner.

Number of samples

Again, we want to determine the number of samples kk per client to achieve a security of the form p \leq 2^{-30}p≤2−30. For that, we need an upper bound for pp for the two-dimensional construction.

Using the tools from the Foundations of DAS paper, we can obtain the bound

p \leq \binom{n}{n\epsilon}\cdot \binom{4mb}{4mb - (b+1)(m+1)} \cdot (\frac{4mb - (b+1)(m+1)}{4mb})^{kn\epsilon} = \binom{n}{n\epsilon}\cdot \binom{4mb}{(b+1)(m+1)} \cdot (1-\frac{(b+1)(m+1)}{4mb})^{kn\epsilon}.p≤(nnϵ)⋅(4mb4mb−(b+1)(m+1))⋅(4mb−(b+1)(m+1)4mb)kn