I would like to thank @aelowsson for the review and feedback provided.

The goal of this analysis is to understand how the Ethereum state (database size per full node) can evolve under increased block gas limits and how repricing (changing effective gas costs for state bytes and burst resources) affects both state growth and burst throughput.

To achieve this, we:

- Project state size under three gas-limit trajectories (base, aggressive, conservative).

- Build and calibrate a simple isoelastic demand model for state creation and burst resource consumption.

- Use that model to compute the new EIP-1559 equilibrium base fee and resulting per-block resource shares when the gas limit and/or the gas price for adding state changes.

- Report scenario comparisons across ranges of price elasticities for state and burst demand.

TLDR

- The state can grow substantially if throughput increases while state creation costs remain relatively cheap. By the middle of 2027, the conservative schedule reaches a total state size of 686 GiB, the base schedule 859 GiB, and the aggressive schedule 1.08 TiB. In all cases, this is above the critical 650 GiB threshold identified by the bloatnet initiative.

- We need to align on what the acceptable level of state growth is for Ethereum in the medium and long term.

- Raising the gas cost for state creation reduces the expected state growth across the explored elasticity regimes, but it slightly reduces burst-resource throughput.

- The throughput loss is more impacted by the burst-demand elasticity than state creation costs. When burst demand is price‑elastic, doubling capacity still yields near‑linear throughput gains and repricing has only a small effect.

- If state creation demand is inelastic, increasing state creation cost is expected to result in a higher base fee when compared with the scenario where state is not repriced. If this demand is elastic, this effect reverts.

1. Why do we care about state growth?

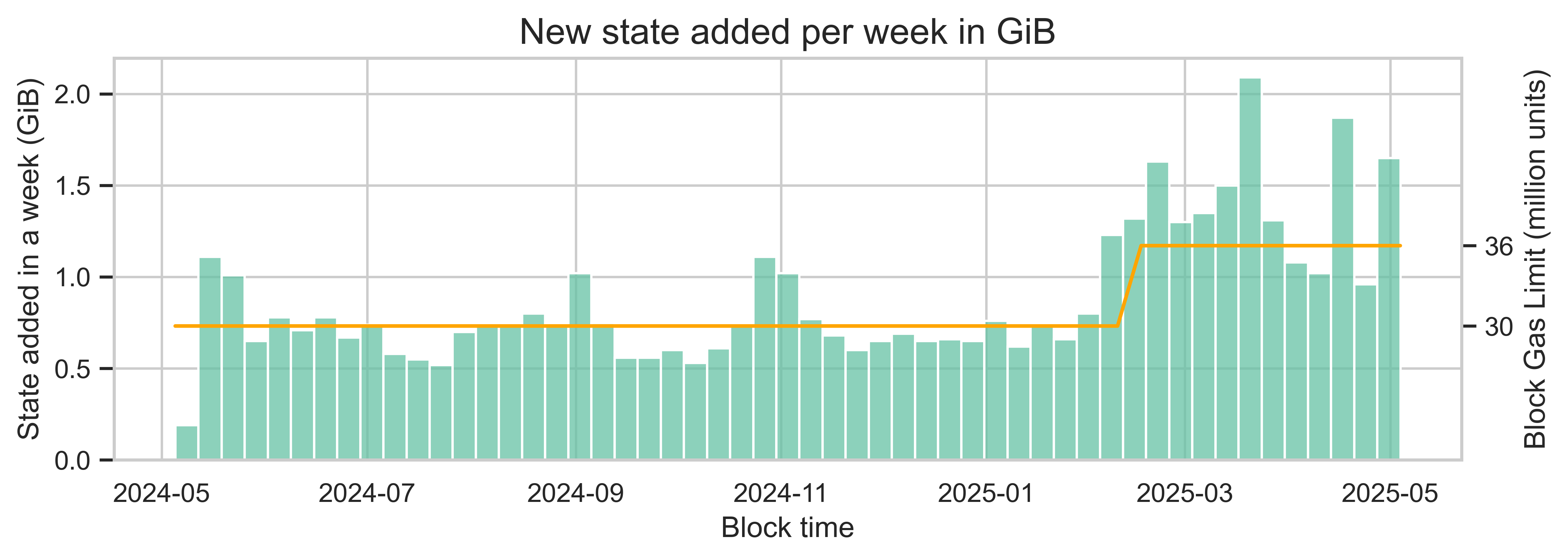

As of May 2025, the current uncompressed database size in a Geth node dedicated to state is ~340 GiB. After increasing the gas limit from 30M to 36M gas units, the median size of new states created each day doubled, from ~102 MiB to ~205 MiB.

The relationship we are seeing in this example is not linear as expected. This is likely due to other factors impacting user behavior. However, all else being equal, we expect a proportional increase in the number of new states created as gas limits increase.

High state growth rates have two negative downstream impacts:

- If state grows faster than disk improvements and the decrease in storage per byte, we will eventually reach a point where validators get priced out and cannot keep up with the disk requirements needed to run an Ethereum validator node.

- The performance of state access operations such as

SSTOREsignificantly depends on the size of the state, with larger states leading to worse execution times for these operations. The bloatnet initiative identified critical bottlenecks in state access patterns with a state size of 650 GiB, resulting in 40% increases in state access times, exponentially higher memory consumption, and longer sync times.

It is still unclear how hardware improvements and client optimizations will affect these bottlenecks; however, given the current focus on scalability and the expected increase in the gas limit, this is an issue we need to look into more carefully. Above all, we need to align on what the acceptable level of state growth for Ethereum is in the medium and long term.

However, in this report, we focus on a slightly different question: how the gas limit is expected to affect state growth, and how gas repricings can alter its trajectory. This is especially relevant for EIP-8037, which is proposed for the upcoming Glamsterdam fork.

2. State growth scenarios under increasing block limits: how big can state get?

To answer this question, we designed three different schedules for gas limit increases from 2025-05-01 through mid-2027:

| Date | Conservative | Base | Aggressive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2025-05-01 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| 2025-07-01 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| 2025-12-01 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 2026-06-01 | 80 | 100 | 150 |

| 2026-12-01 | 150 | 300 | 500 |

| 2027-06-01 | 200 | 400 | 700 |

Then, for each schedule, we compute the corresponding state growth rate, assuming a proportional relationship between state growth per day and gas limit and a baseline measured state creation rate of 205 MiB/day at a 36M gas limit:

new_state_per_day = 205 MiB * (G / 36M)

With this, we get the following state growth rates per day at each gas limit change day:

| Date | Conservative (MiB/day) | Base (MiB/day) | Aggressive (MiB/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2025-05-01 | 205 | 205 | 205 |

| 2025-07-01 | 256 | 256 | 256 |

| 2025-12-01 | 342 | 342 | 342 |

| 2026-06-01 | 456 | 569 | 854 |

| 2026-12-01 | 854 | 1708 | 2847 |

| 2027-06-01 | 1139 | 2278 | 3986 |

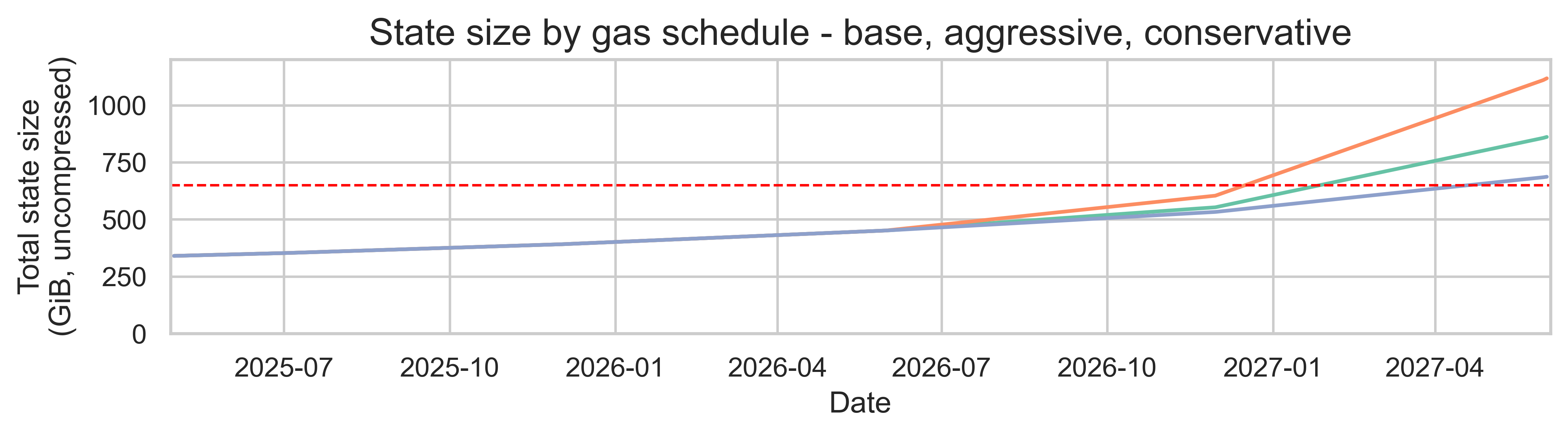

The next plot shows total state size in GiB over the next 2 years for the three gas schedules.

Under proportional scaling (keeping the same gas composition), increasing the block limit linearly increases the daily state creation (because we scale the measured 205 MiB/day by the gas limit ratio). Because daily additions compound, the total state size diverges over months and years between gas schedules. By the middle of 2027, the conservative schedule reaches a total state size of 686 GiB, the base schedule 859 GiB, and the aggressive schedule 1.08 TiB. In all cases, this is above the critical 650 GiB threshold identified by the bloatnet initiative.

3. How does repricing impact state growth and throughput?

Now that we have identified potential scenarios of state growth under no pricing changes, we can analyze how increasing the gas price for state creation operations affects state growth and scalability.

3.1 Model and derivation

We start by defining a simple model that allows us to estimate the average daily state growth and the amount of gas available in a block for burst operations (compute, state access, and data).

Model inputs

- GG: The block gas limit.

- bb: The equilibrium base fee bb in gwei.

- g_\text{state}gstate: The gas cost per new byte added to the state byte.

- g_\text{burst}gburst: The gas costs for each second of burst resource usage.

- S(p)S(p): The demand curve for state creation, measured as the total number of net state bytes willing to be added in a block at the price pp. Note that pp is cost in gwei of adding one byte to state and is computed as p=b\cdot g_\text{state}p=b⋅gstate.

- B(p)B(p): The demand curve burst resource usage, measured as the number of slot time in seconds willing to be added in a block at the price pp. In this case, p=b\cdot g_\text{burst}p=b⋅gburst.

Model assumptions

- The base fee follows the EIP-1559 design, where block usage above 50% of GG leads to an increase in the base fee for the next block, wile a block usage below 50% of GG leads to a decrease in the base fee for the next block.

- With current design, blocks occupy on average 50% of GG, with 30% of that gas allocated to state creation and the remaining to burst resources.

- The average block is achieved at equilibrium, when 50% of GG is sufficient to cover the demand for state creation and burst resource usage at the price pp.

- Both demand curves are modelled with two independent isoelastic models:

Here, we assume independent isoelastic demands for tractability. In practice, however, demand for state creation and burst resources is likely correlated: a change in the effective price of state bytes will affect demand for burst seconds (and vice‑versa). A joint multivariate demand specification with cross‑price elasticities would better capture substitution or complementarity between resources, but it introduces additional parameters and identification challenges.

Scenario

- Gas limit increases by a factor of nn, i.e., G = n \, G^0G=nG0

- State gas costs increases by a factor of mm, i.e., g_\text{state} = m \, g_\text{state}^0gstate=mg0state

We expect the base fee to decrease until reaching a new equilibrium where both more state and more burst resources are used.

Base derivation

Let the per-block equilibrium usage at price pp be

- State bytes: S(p)=S(b g_\text{state})S(p)=S(bgstate)

- Burst seconds: B(p)=B(b g_\text{burst})B(p)=B(bgburst)

The gas used in a block at base fee b is defined as:

For the scenario, EIP-1559 drives bb toward the value b^*b∗ such that:

At this new equilibrium, we get the following per-block usage:

- S^* = S(b^* \, m\, g_\text{state}^0)S∗=S(b∗mg0state), which leads to an average state growth of 2,628,000\cdot S^*2,628,000⋅S∗ bytes per year. Note that 2,628,0002,628,000 is the number of blocks per year (i.e., one every 12 seconds)

- B^* = B(b^* g_\text{burst}^0)B∗=B(b∗g0burst)

and the following shares per resource type:

- \text{Share}_\text{state}=\frac{m\,g_\text{state}^0S^*}{0.5\, n\, G_\text{limit}^0}Sharestate=mg0stateS∗0.5nG0limit

- \text{Share}_\text{burst}=1-\text{Share}_\text{state}Shareburst=1−Sharestate

Calibration

With current G=G^0G=G0, equilibrium b=b^0b=b0 and initial gas prices g_\text{state}^0g0state and g_\text{burst}^0g0burst, we get:

- g_\text{state}^0 S(b^0 g_\text{state}^0)= 0.3 \cdot 0.5 \cdot G^0 = 0.15\, G^0g0stateS(b0g0state)=0.3⋅0.5⋅G0=0.15G0

- g_\text{burst}^0 B(b^0 g_\text{burst}^0)= 0.7 \cdot 0.5 \cdot G^0 = 0.35\, G^0g0burstB(b0g0burst)=0.7⋅0.5⋅G0=0.35G0

With this, we can calibrate A_sAs and A_bAb as:

A_s = S(p)p^{\varepsilon_s} = \frac{0.15\,G^0}{g_\text{state}^0}\,(b^0g_\text{state}^0)^{\varepsilon_s}As=S(p)pεs=0.15G0g0state(b0g0state)εs

A_b = B(p)p^{\varepsilon_b} = \frac{0.35\,G^0}{g_\text{burst}^0}\,(b^0g_\text{burst}^0)^{\varepsilon_b}Ab=B(p)pεb=0.35G0g0burst(b0g0burst)εb

Under this choice, for any bb we get the following formula for gas used in the block under equilibrium:

We can also estimate g_\text{burst}^0g0burst from gas limit and the current state growth rate. Here we are taking an average cost assuming a 50% gas limit utilization:

For the burst resources, we will price based on the worse case block, i.e., assume that if the block was full of burst resource operations until the block limit, it would take 2 seconds to execute:

From this, we can directly derive the base throughput for burst resources:

Scenario derivation

In the scenario, G=n\,G^0G=nG0, g_\text{state}=m\,g_\text{state}^0gstate=mg0state and g_\text{burst}=g_\text{burst}^0gburst=g0burst, which makes the total gas used in the block under equilibrium be:

Also, at equilibrium, we are using 50% of the new gas limit so:

We can compute the roots of this polynomial to find the equilibrium base fee b^*b∗. If the polynomial has a root r \in \mathopen] 0,1\mathclose[r∈]0,1[, then b^* = b^0 \, rb∗=b0r. From this, we can compute the per-block usages and gas shares as defined in the base derivation.

In the following sections, we consider the impact of three scenarios:

- Base (no repricing): n=2n=2 (double gas limit), m=1m=1 (state gas cost unchanged)

- Double state gas prices: n=2, m=2n=2,m=2

- Triple state gas prices: n=2, m=3n=2,m=3

In all cases, we assume that the gas limit doubles (n=2n=2).

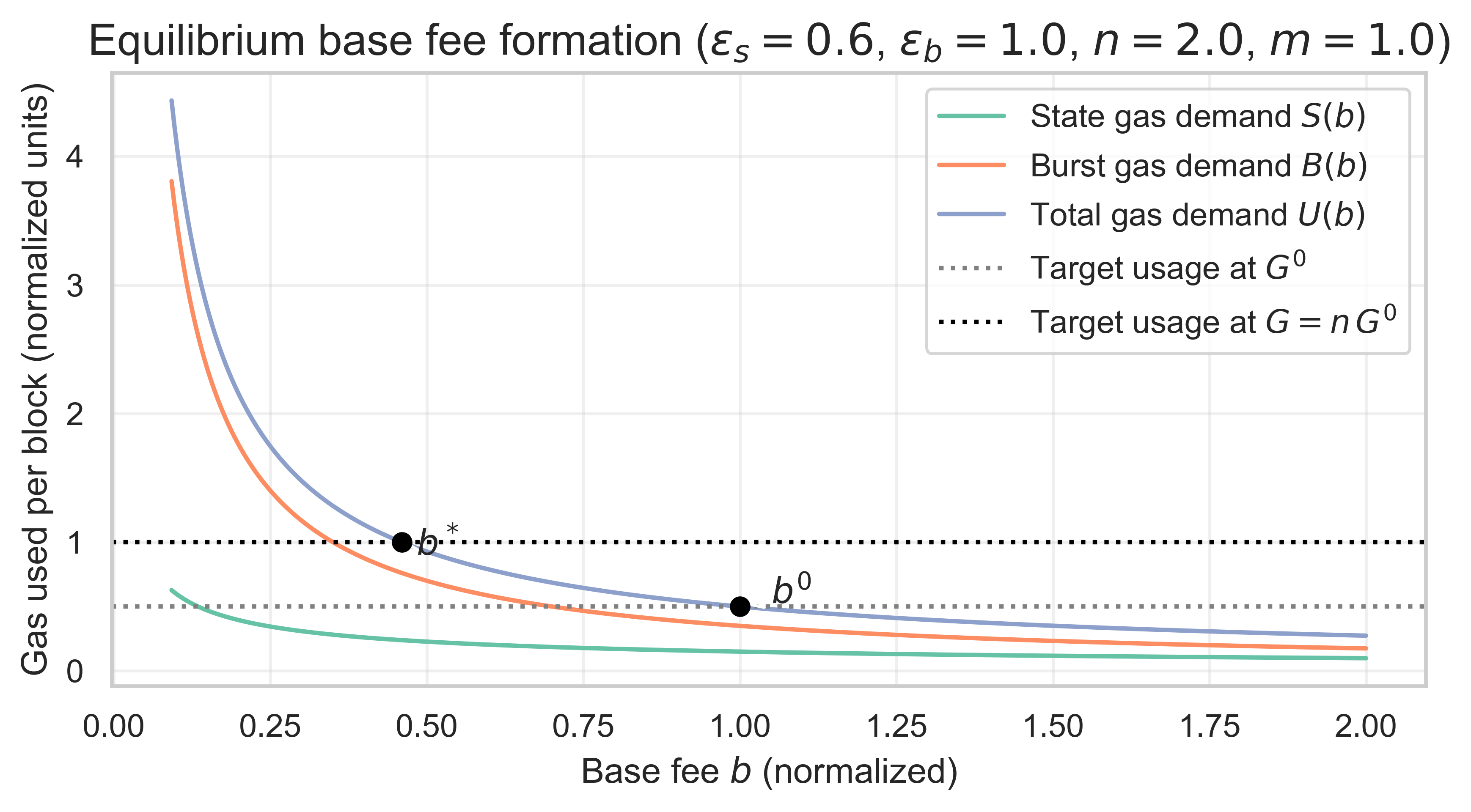

For each scenario, we sweep \varepsilon_sεs and \varepsilon_bεb across a grid (0.1 to 1.5) and solve for b^*b∗. With the equilibrium base fee b^*b∗, we then compute S^*S∗, B^*B∗, the annual state growth in GiB, and the resource gas shares. To help visualize this, the following graph shows this new equilibrium for the base scenario assuming \varepsilon_s=0.6εs=0.6 and \varepsilon_b=1εb=1

3.2 Impact of repricing on the share of gas used by state creation

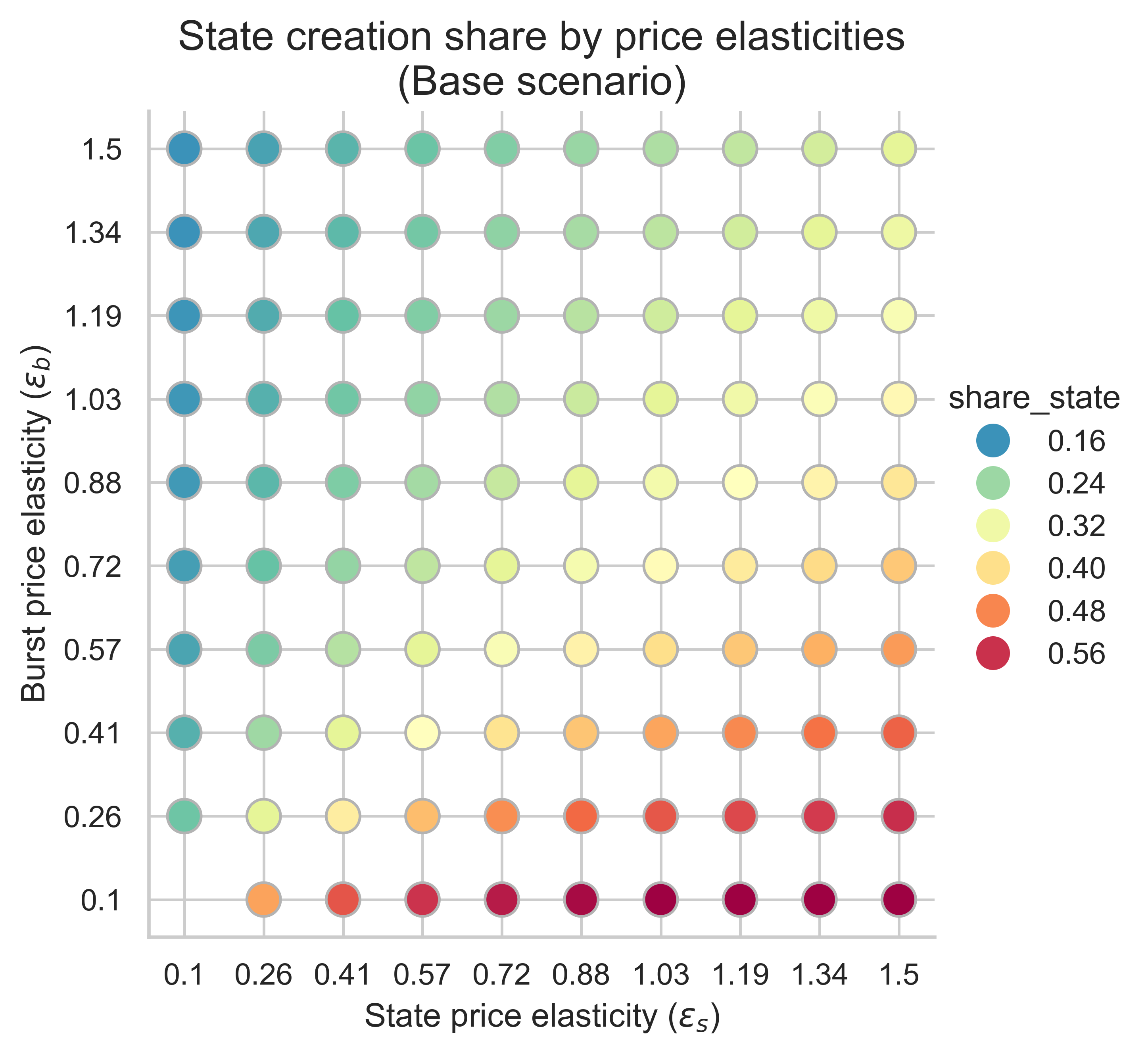

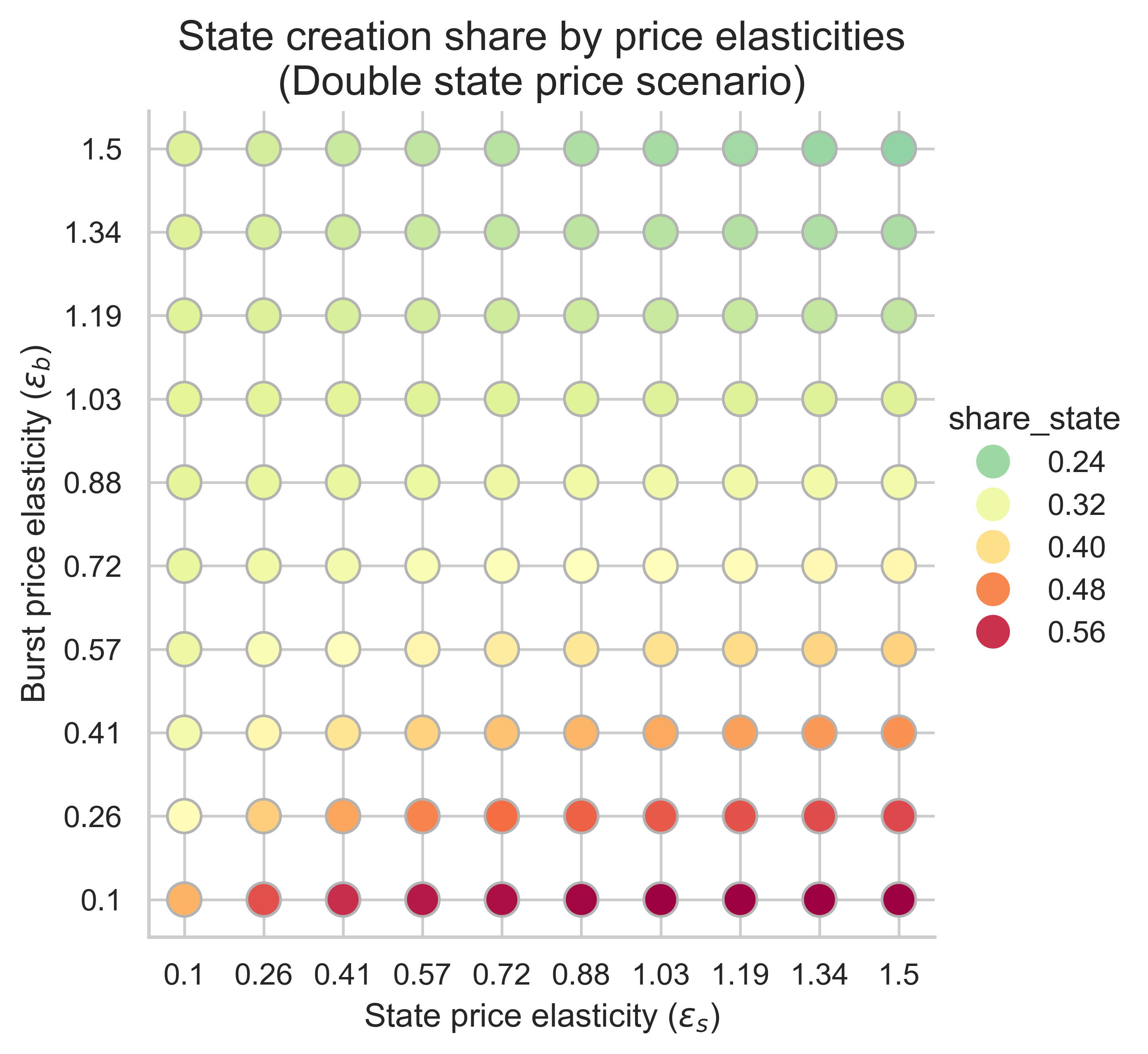

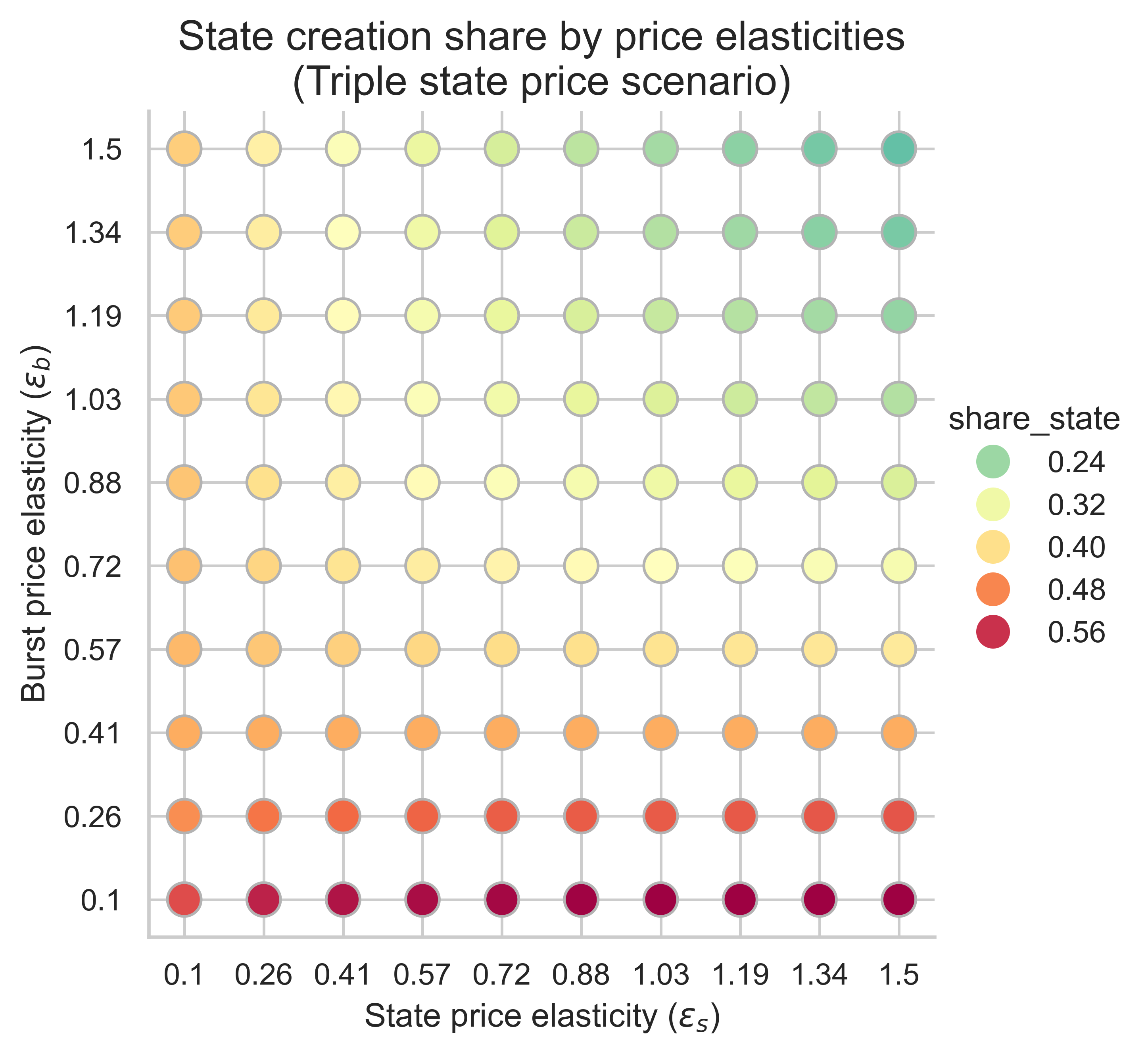

The following plots show the share of gas used in the equilibrium block by state creation operations for all price elasticity combinations (\varepsilon_s, \varepsilon_b)(εs,εb).

With m = 1m=1 (no repricing) and n = 2n=2 (double gas limit), the share of block gas consumed by state creation increases relative to the current 30% when demand for state creation is more elastic than demand for burst resources. Thus, if state creation adapts more to changing prices than to burst resource usage, there is a risk that scaling up gas limits shifts more block capacity to state creation, as more state-creation demand will flood the block to take advantage of cheaper base fees.

Increasing mm (making state creation more expensive) impacts the block share dedicated to state creation in the low-elasticity regimes of state and the high-elasticity regimes of burst resources:

- When demand for state creation has low-elasticity (the left side of the plots), we see a higher share of gas dedicated to state creation operations, with increasing magnitude the larger mm is.

- Conversely, when both demands have high elasticity (top-right corner), the effect is reversed, with a decreasing portion of the block dedicated to state creation when compared with the m=1m=1 scenario. The magnitude of the change depends again on mm.

- The cases with the highest share of state creation occur when demand for burst resources has low elasticity (bottom side of the plot). In this case, increasing the cost of state creation has no effect.

In conclusion, increasing the gas costs of state creation may have a positive or negative effect on the share of the equilibrium block dedicated to state creation. This depends on the elasticity regime. Yet, when the share of block space dedicated to state creation is already high in the base scenario (m=1m=1), then increasing the gas costs of state creation does not impact this share significantly. In other words, if we are in an elasticity regime that will already have a high share of state creation gas under increasing block limits, increasing its gas prices won’t have a significant effect.

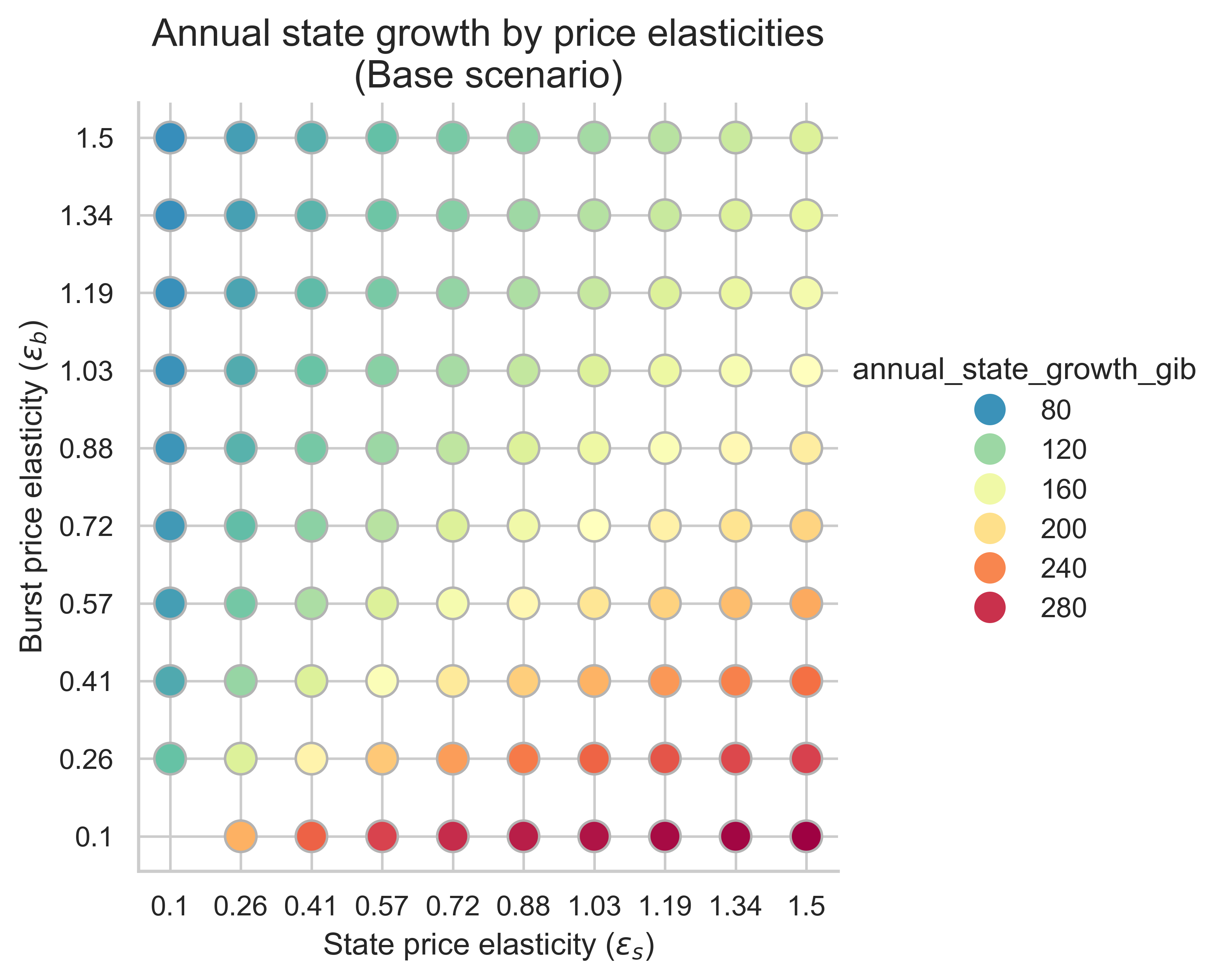

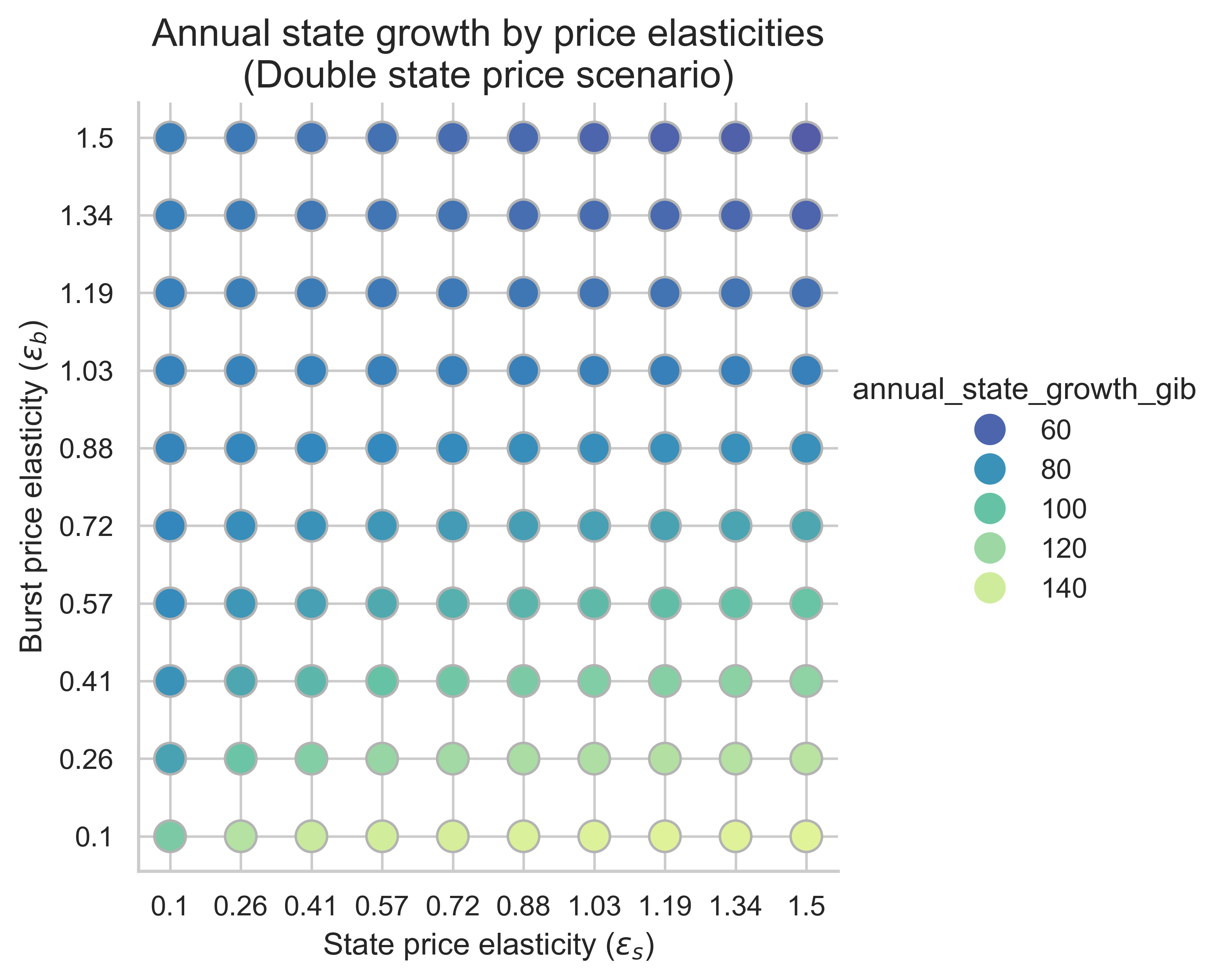

3.3 Impact of repricing on the annual state growth

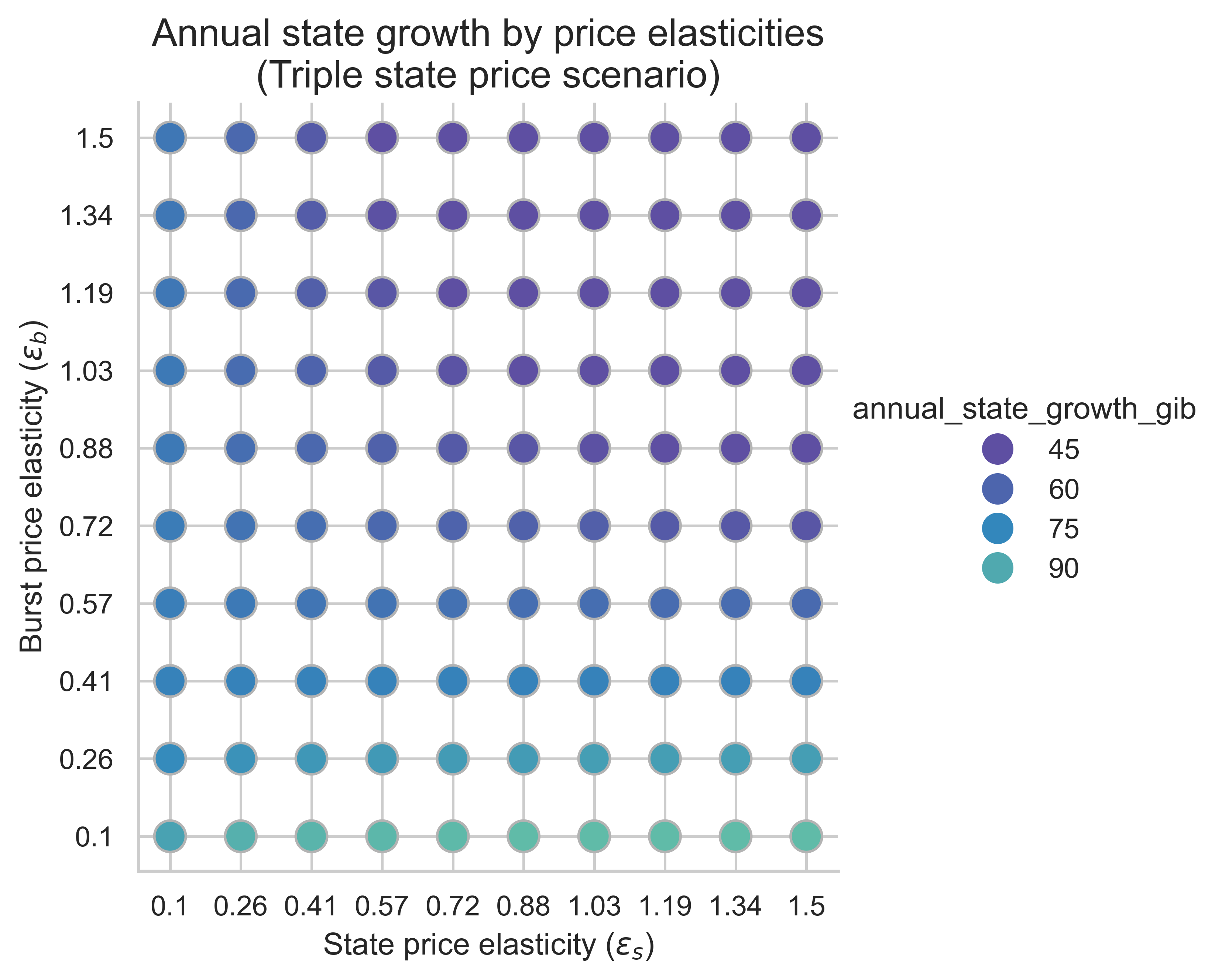

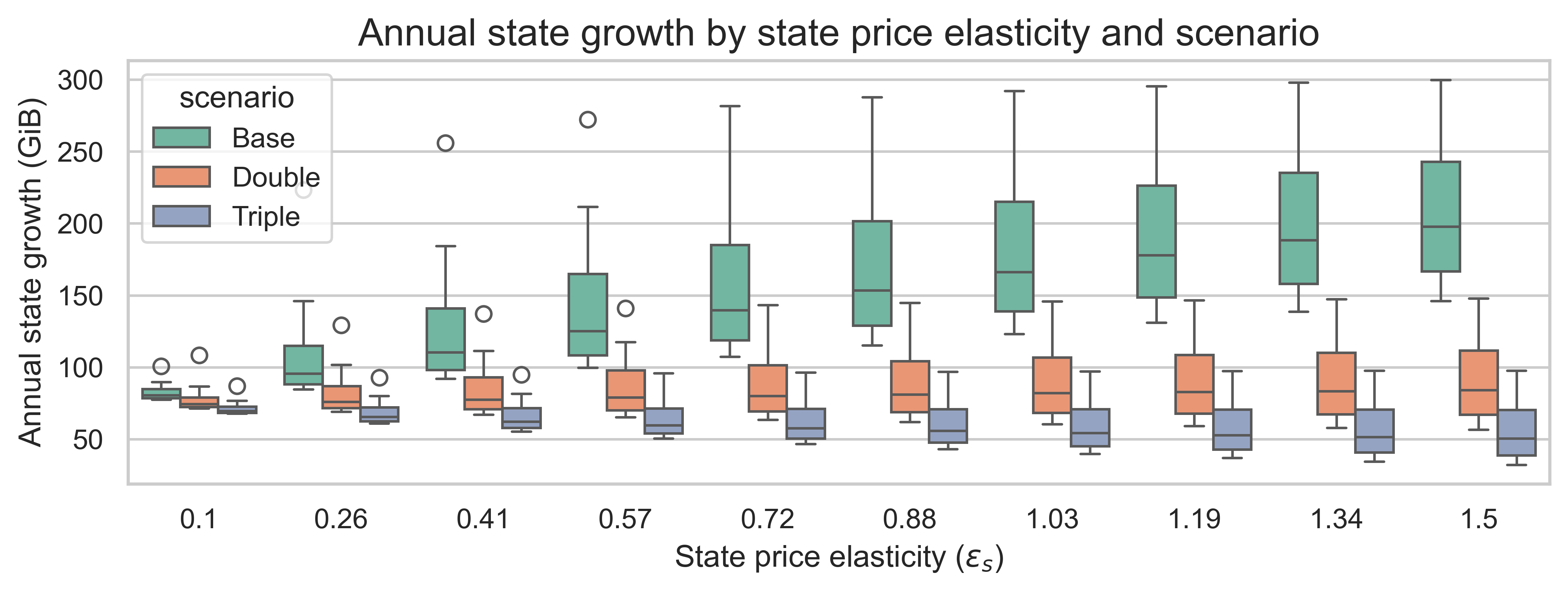

The following plots show the annual state growth for all price elasticity combinations (\varepsilon_s, \varepsilon_b)(εs,εb). Here we assume that the average block is the equilibrium block. This metric is key to understand how effective increasing the cost of state creation operations is at mitigating state growth.

Unsurprisingly, increasing the costs of state-creation operations decreases the state growth rate across all elasticity regimes compared with the scenario without repricing. This indicates that increasing the gas cost of state creation is effective at mitigating state growth across a wide range of price elasticities.

Increasing the gas cost of state creation has another interesting effect. We can observe it by plotting the annual state growth against the state demand elasticity \varepsilon_sεs for each scenario. The variation on each boxplot is due to the burst demand elasticity \varepsilon_bεb.

- No reprice: higher \varepsilon_s \impliesεs⟹ more state growth

- Reprice equal to the increase in block limit: higher \varepsilon_s \impliesεs⟹ no change on the median state growth

- Reprice higher than the increase in block limit: higher \varepsilon_s \impliesεs⟹ less state growth

We should note that the demand elasticity of burst resources also affects state growth: the lower the elasticity, the higher the state growth rate across all scenarios.

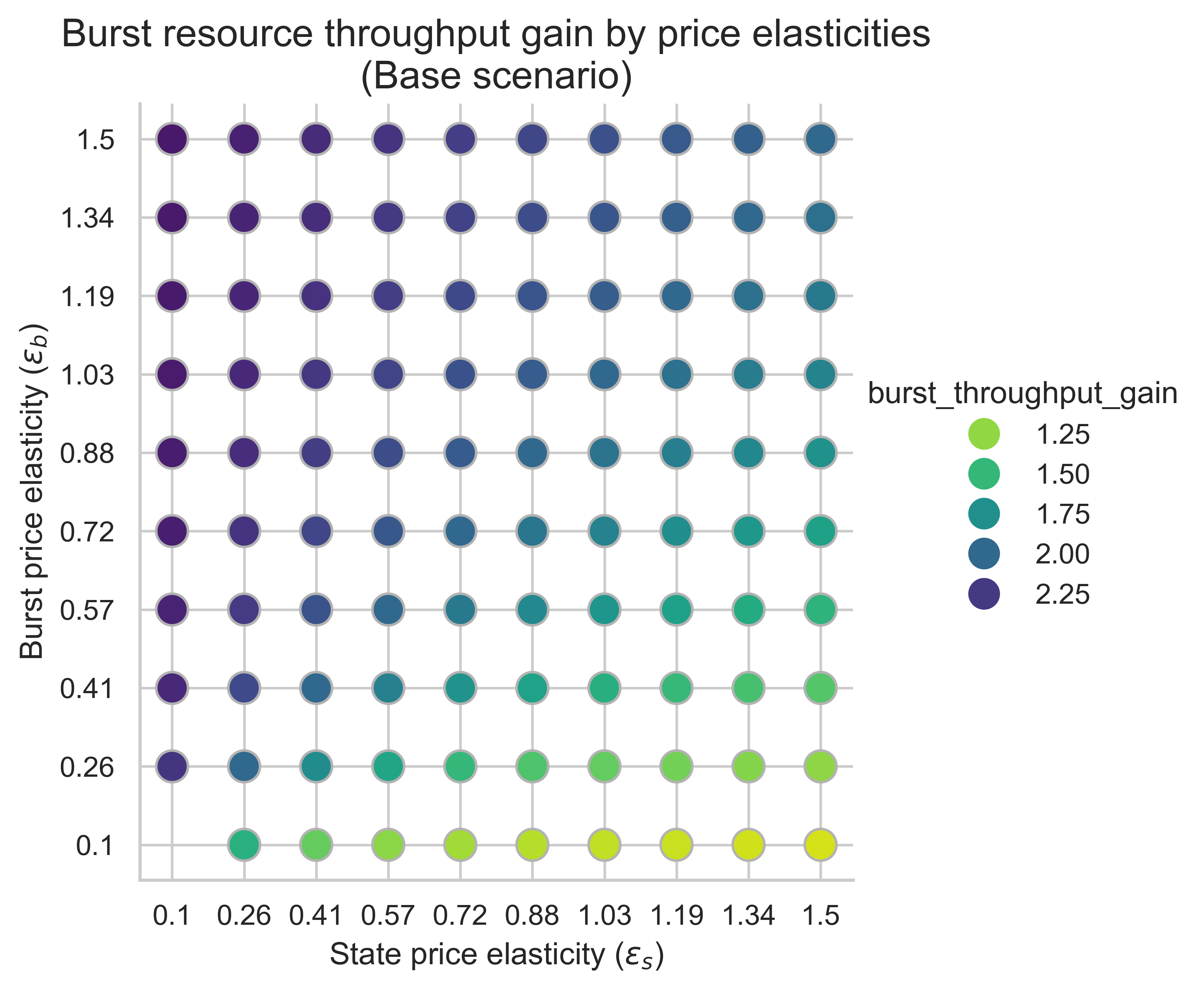

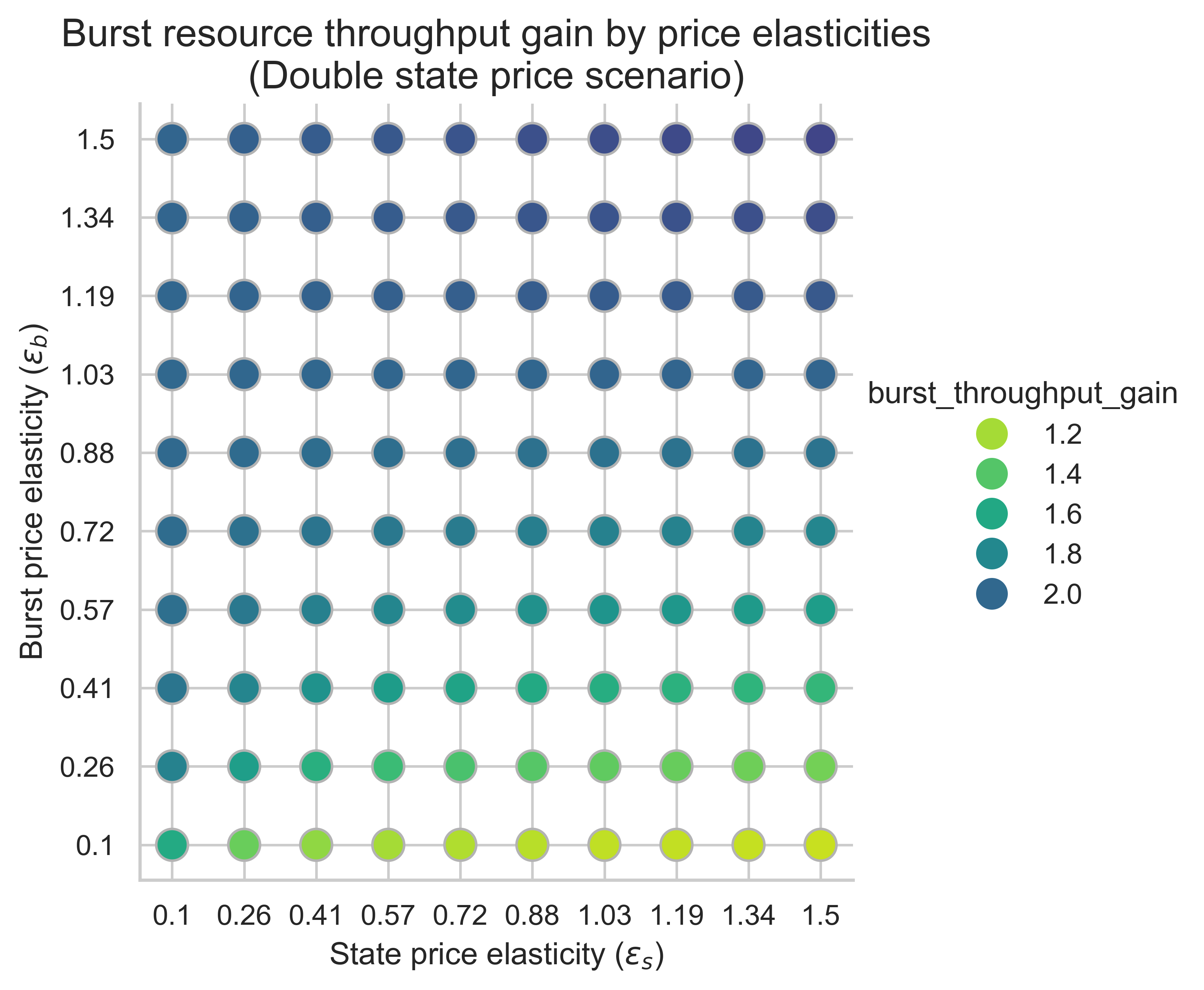

3.4 Impact of repricing on the throughput of burst resources

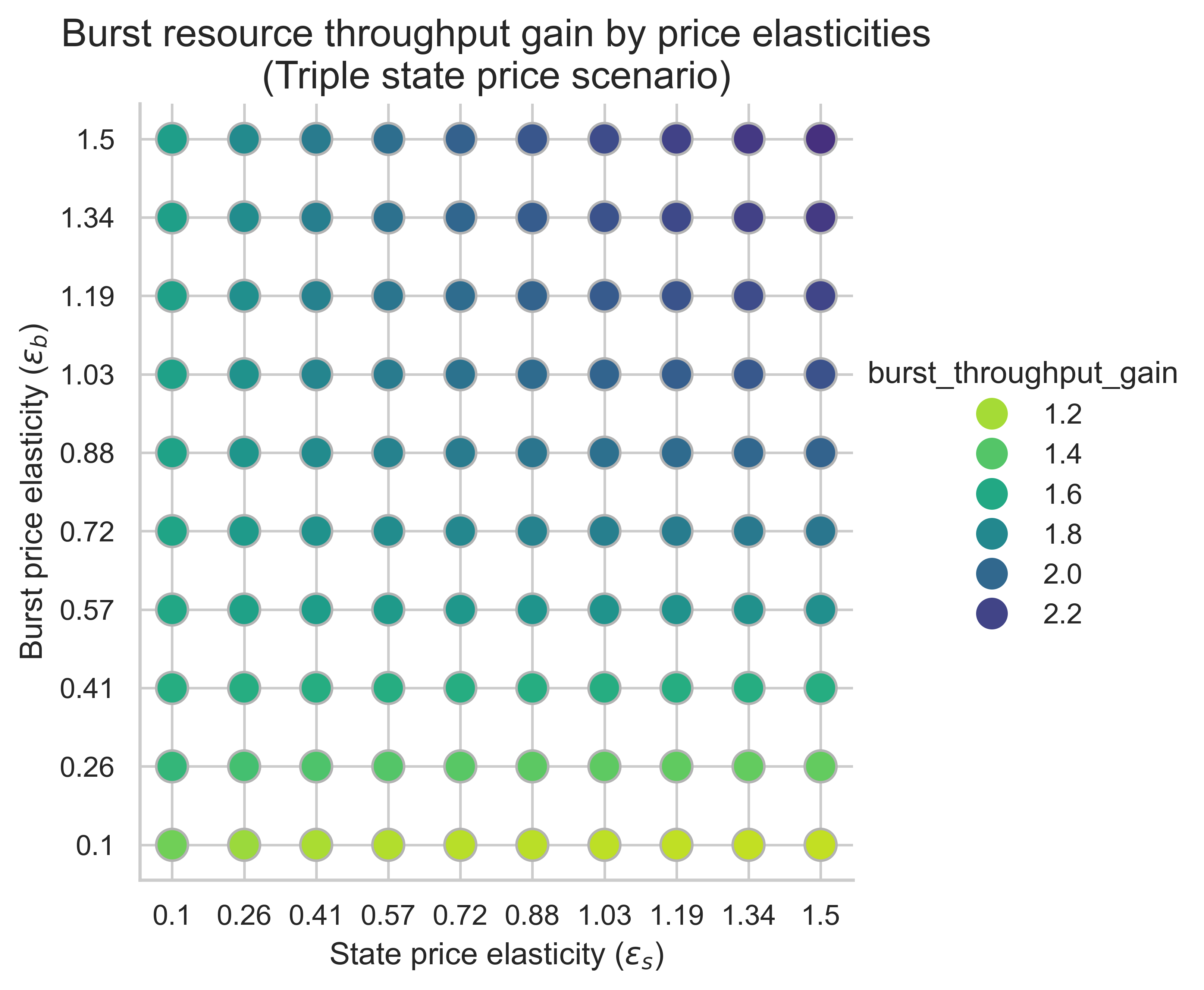

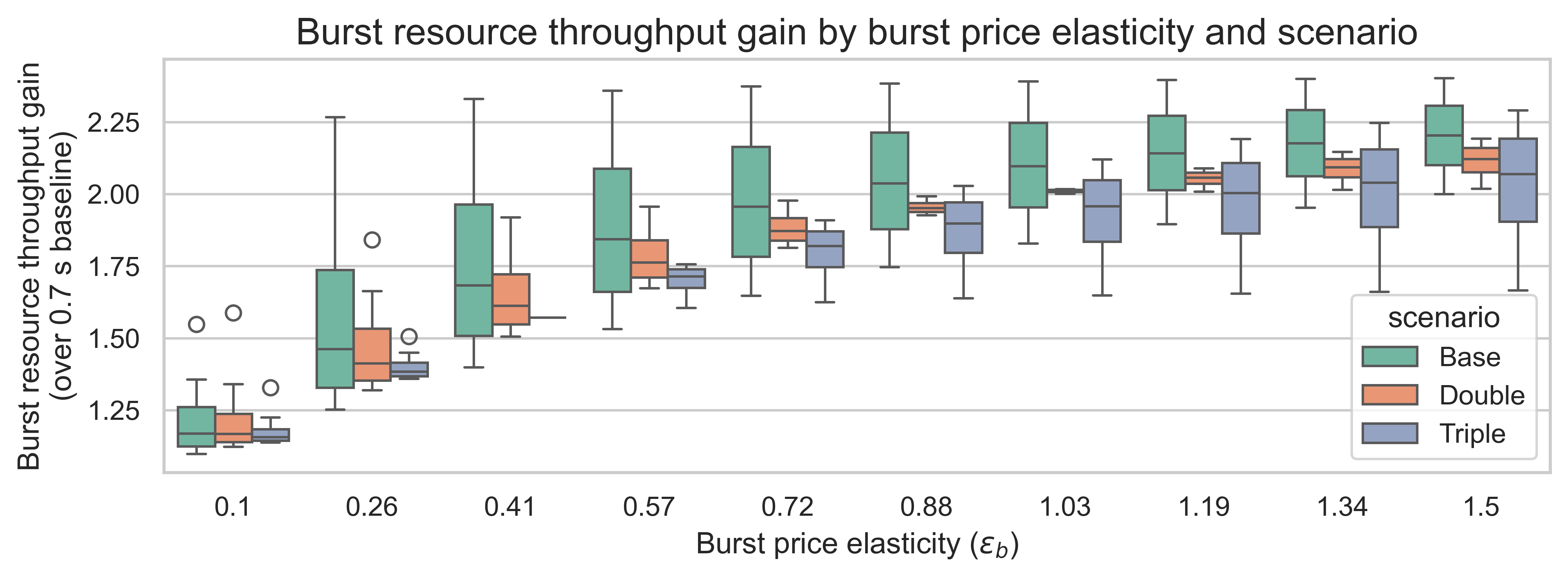

The following plots show the throughput gains on burst resources in the equilibrium block for all price elasticity combinations (\varepsilon_s, \varepsilon_b)(εs,εb). The gain is computed over the 0.7-second baseline throughput.

This metric is essential for measuring the impact on scalability of increasing state-creation costs. If we double the available gas, do we still observe at least double the throughput for burst resources? Recall that the baseline throughput is 0.7 seconds.

In all three scenarios, the dominant driver of burst-throughput gains is the burst-side price elasticity, \varepsilon_bεb. As \varepsilon_bεb rises, we see an increasing gain over the 0.7-s baseline:

- When burst demand is sufficiently price-elastic (top side of the plots), doubling capacity translates to ~double (or slightly more) burst throughput.

- When burst demand is inelastic (bottom side of the plots), doubling capacity translates to less than double the burst throughput.

By contrast, the horizontal variation with state elasticity \varepsilon_sεs is more complex. Gains decrease slightly as \varepsilon_sεs increases when m = 1m=1. As for m=2m=2 or m=3m=3, the highest throughput gains on burst resources are achieved when both price elasticities are high.

In the following plot, we can see more clearly the impact of raising state creation costs on throughput. The variation on each boxplot is due to the state demand elasticity \varepsilon_sεs.

In general, higher costs slightly decrease the throughput gains. However, the effect is small when compared with the impact of the demand elasticity of burst resources. If we are in a regime with high \varepsilon_bεb, then increasing state creation affects throughput by less than 25%.

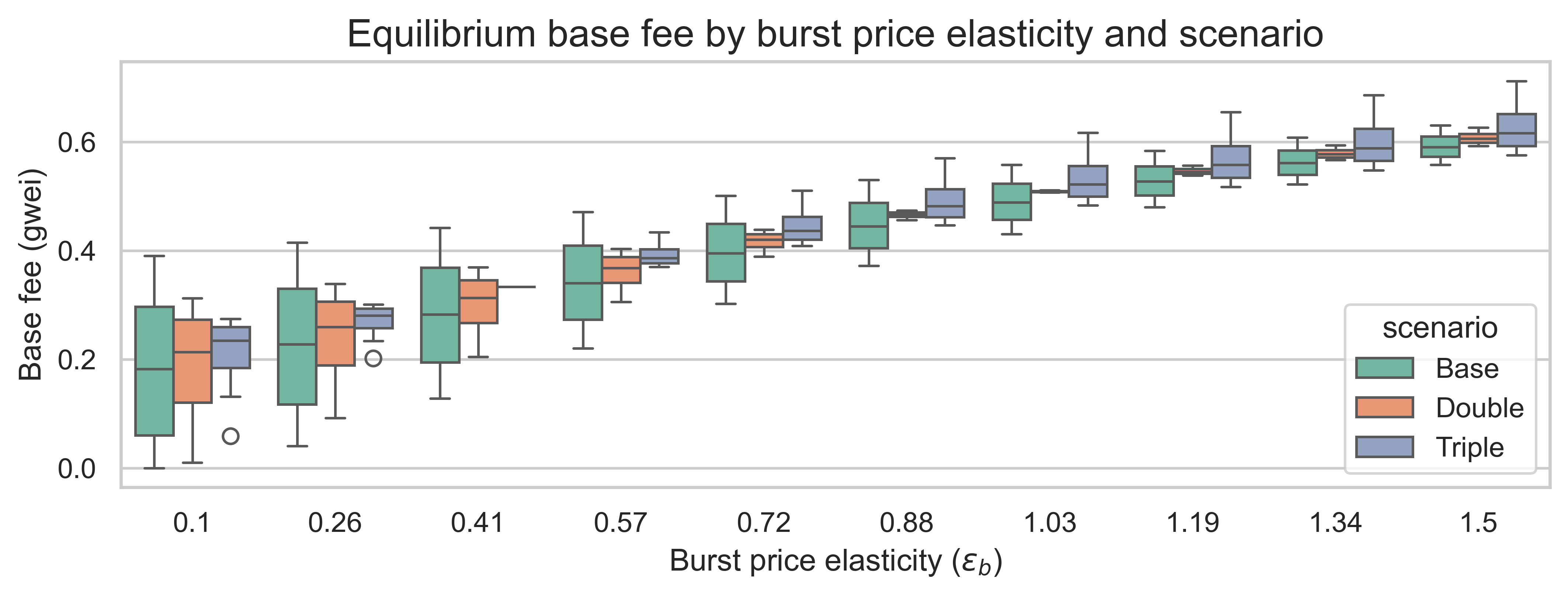

3.5 Equilibrium fee

The final metric we want to analyze is the equilibrium base fee. We expect this fee to be lower than the baseline b^0=1b0=1. However, how much lower does the fee get under different elasticity regimes and repricings? The following plot shows the equilibrium base fee for the three repricing scenarios and the burst demand elasticities. The variation on each boxplot is due to the state demand elasticity \varepsilon_sεs.

Across all three pricing scenarios, the equilibrium base fee increases with the burst-side price elasticity: moving from very inelastic burst demand (\varepsilon_b\approx0.1εb≈0.1) to highly elastic (\varepsilon_b\approx1.5εb≈1.5) roughly triples the median base fee. When elasticity is high, more demand will be available to fill up the available gas, thus leading to a higher base fee.

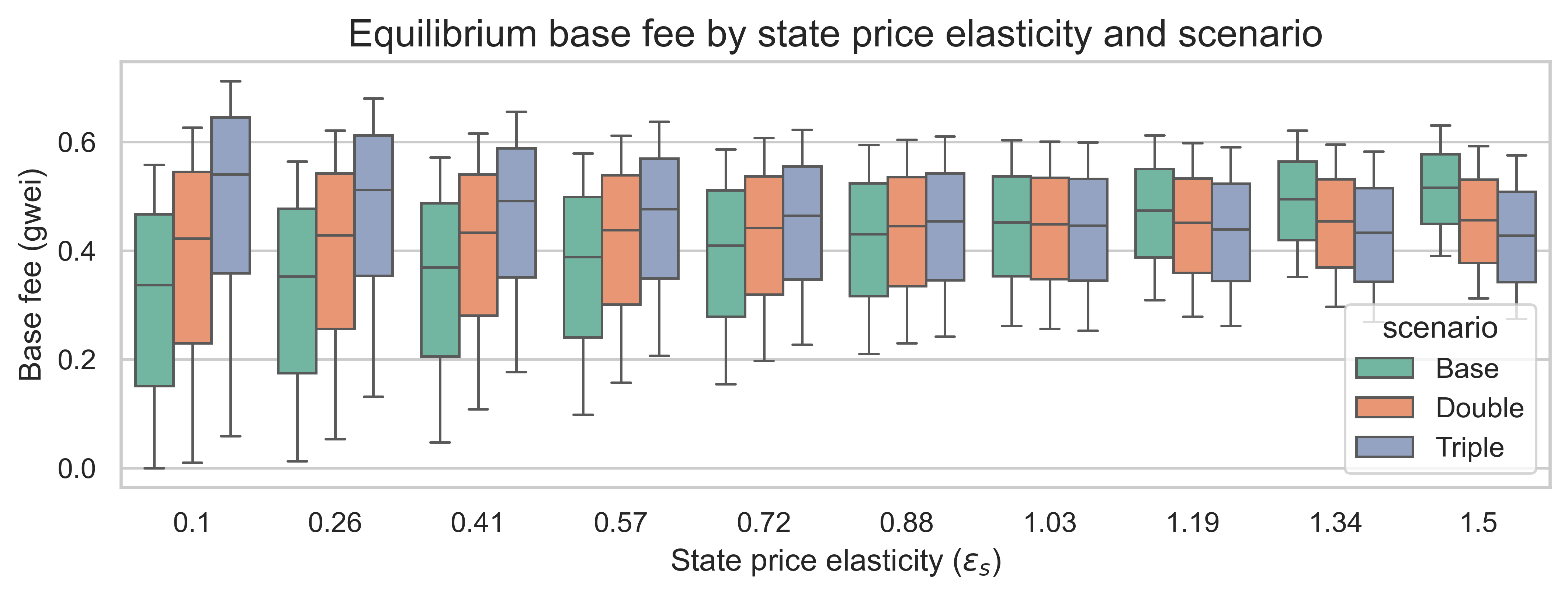

What about state demand elasticity? The following plot shows the equilibrium base fee for the three repricing scenarios and the state demand elasticities. The variation on each boxplot is due to the burst demand elasticity \varepsilon_bεb.

Interestingly, we don’t see the same linear relationship between the base fee and state demand, with the median base fees maintaining similar ranges independently of the state demand elasticity. However, the elasticity regime has an impact on the ordering across scenarios:

- When state demand is inelastic (left side of the plot), higher state prices lead to higher equilibrium fees. In this case, making the state more expensive does not affect demand as much, so more gas is used for the same state demand.

- When state demand is elastic (right side of the plot), higher state prices lead to lower equilibrium fees. In this case, the demand for state creation responds more aggressively to increases in state costs, thus lowering the base fee.

4. Discussion and next steps

The first takeaway is that, under our simplified model, increasing the cost of state-creation operations effectively mitigates state growth across all price elasticity regimes. There is simply insufficient gas to grow the state by as much as in the base pricing scenario. However, this still comes at a cost of slightly lower throughput gains for burst resources. This effect is compounded by the elasticity of demand for burst resources — the more elastic they are, the higher the throughput gains achieved across all pricing scenarios. If state creation demand is inelastic, increasing state creation costs is expected to result in a higher base fee than in the scenario where state is not repriced.

A natural question is where the real system sits in the (\varepsilon_s,\varepsilon_b)(εs,εb) grid. Our preliminary empirical analysis suggests that short-run demand for state creation is moderately inelastic: a 1% increase in the base fee in USD is associated with only a ~0.6% decrease in new state created per unit of gas over the following days. Interpreted through the isoelastic lens, this points to \varepsilon_s \approx 0.6εs≈0.6 for the aggregate state-creation workload in the short run. That is consistent with the intuition that many state-heavy actions (opening positions, creating contracts, minting tokens, committing data to rollups, etc.) are driven by longer-lived economic decisions and protocol-level policies that do not adjust instantaneously to price changes. We should add that spam contracts such as XEN are expected to induce a floor price, since whenever the overall cost of state creation falls below a certain threshold, bots will flood the network with state-heavy transactions, thereby increasing the base fee for future blocks.

For burst resources, we do not yet have comparable estimates, but there are reasons to expect a higher elasticity, at least for a large share of the workload. Many burst-dominated activities (arbitrage, liquidation, MEV search, latency-sensitive trading) are explicitly fee-constrained and can back off quickly w