In 1849, the California Gold Rush saw countless people with dreams of striking it rich flock to the American West.

German immigrant Levi Strauss originally wanted to join the gold rush, but he keenly discovered another business opportunity: the miners' trousers were often torn and they urgently needed more durable work clothes.

So he made a batch of jeans out of canvas and sold them to gold miners, thus creating a clothing empire called "Levi's". However, most of those who actually participated in the gold rush lost everything.

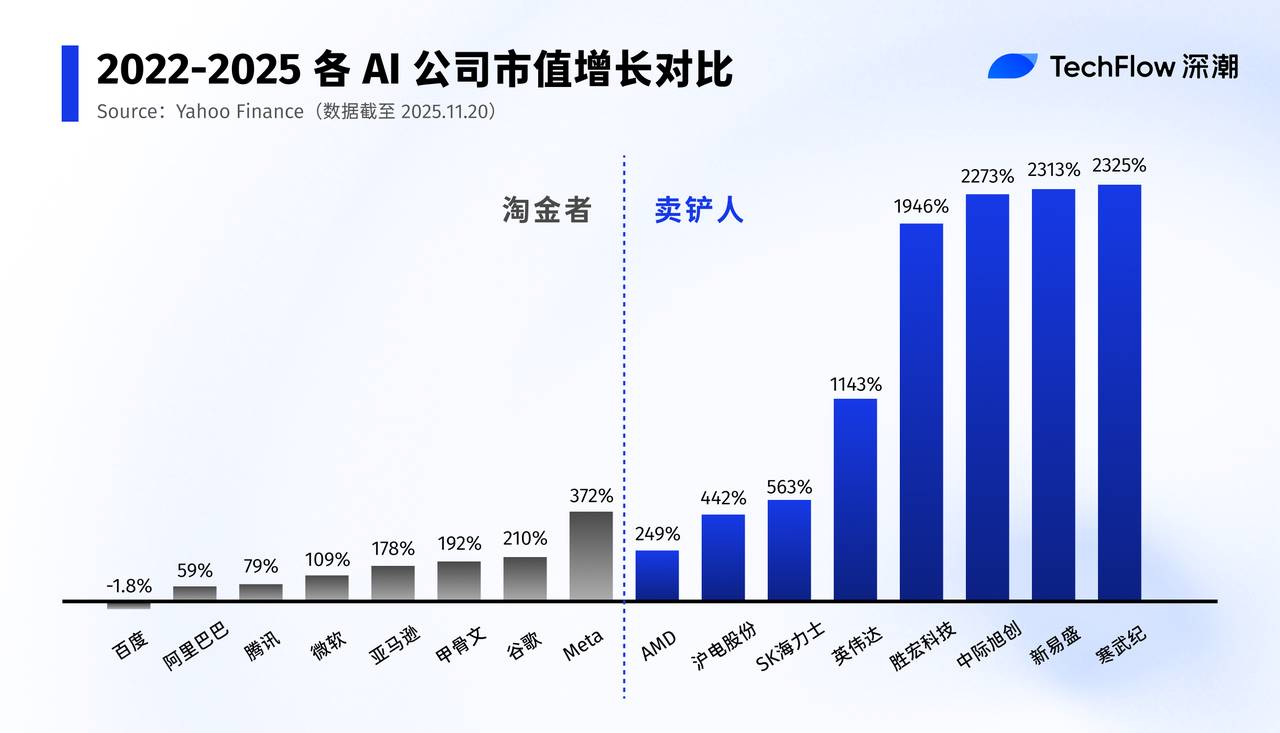

On November 20, 2024, Nvidia once again delivered an "unbelievable" financial report.

Q3 revenue hit a record $57 billion, up 62% year-over-year; net profit was $31.9 billion, a staggering 65% year-over-year increase. The latest generation of GPUs remains a scarce commodity that "money can't always buy," and the entire AI industry is working to develop them.

Meanwhile, in the cryptocurrency world on the other side of the cyberspace, the same scenario is playing out.

From the ICO bull market in 2017 to the DeFi summer in 2020, and then to the Bitcoin ETF and Meme wave in 2024, in each narrative and each wave of get-rich-quick stories, retail investors, project teams, and VCs have been constantly changing, but only exchanges like Binance have always stood at the top of the food chain.

History always rhymes.

From the California Gold Rush of 1849 to the cryptocurrency craze and the AI wave, the biggest winners are often not the "gold miners" who directly compete, but those who provide them with the "shovels. " "Selling shovels" is the strongest business model for navigating cycles and reaping the benefits of uncertainty.

The AI gold rush has made Nvidia rich.

In the public's perception, the protagonist of this wave of AI is undoubtedly the large model represented by ChatGPT, an intelligent agent that can write copy, draw, and write code.

However, from a business and profit perspective, the essence of this wave of AI is not an "explosion of applications," but an unprecedented revolution in computing power.

Like the California Gold Rush of the 19th century, tech giants like Meta, Google, and Alibaba are all gold miners, launching an AI gold rush.

Meta recently announced that it will invest up to $72 billion in artificial intelligence infrastructure this year, and said that spending will be even higher next year. CEO Mark Zuckerberg said he would rather risk "missing out on hundreds of billions of dollars" than fall behind in the research and development of superintelligence.

Companies such as Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and OpenAI have all made record capital expenditures in the field of AI.

Tech giants are going crazy, and Jensen Huang is grinning from ear to ear. He is the Levi Strauss of the AI era.

Every company that wants to build large-scale models needs to purchase GPUs and rent GPU cloud services on a large scale. Each model iteration consumes a huge amount of training and inference resources.

If the model can't compete with the competition and the application can't find a clear path to commercialization, it can be scrapped and started over, but the GPUs that have been purchased and the computing power contracts that have been signed have already been paid for in real money.

In other words, everyone is still exploring the questions of "whether AI can change the world" and "whether AI applications can generate long-term profits." But if you want to participate in this game, you must first pay an "entry tax" to the computing power provider.

Nvidia happens to be at the very top of this computing power food chain.

It has almost monopolized the high-performance training chip market. The H100, H200 and B100 have become the "golden shovels" that AI companies are vying for. It breaks down from the GPU to the software ecosystem (CUDA), development tools and framework support, further forming a dual moat of technology and ecosystem.

It doesn't need to bet on which big model will win; it just needs the entire industry to keep "betting": betting that AI can create a certain future and support higher valuations and budgets.

In the traditional internet, Amazon's AWS once played a similar role. Whether a startup could survive was one thing, but sorry, you had to pay for cloud resources first.

Of course, Nvidia is not an isolated entity; behind it is an entire "shovel supply chain," and they are also big winners in the AI wave.

GPUs require high-speed interconnects and optical modules, and A-share listed companies such as New E-Sun, InnoLight Technology, and Tianfu Communication have become an indispensable part of this "shovel," with their stock prices rising several times this year.

Data center transformation requires a large number of server racks, power systems, and cooling solutions. From liquid cooling and power distribution to data center infrastructure, new industry opportunities are constantly emerging. Storage, PCB, connectors, packaging and testing—all component manufacturers associated with "AI servers" are taking turns reaping valuations and profits in this wave.

This is the terrifying aspect of the "selling shovels" model:

Gold prospectors may lose money, and gold mining may fail, but as long as people keep digging, the shovel sellers will never lose money.

While large-scale models are still struggling with "how to make money," the computing power and hardware supply chain is already steadily generating revenue.

Crypto shovel seller

If Nvidia is the seller of AI shovels, then who is the seller of Crypto shovels?

The answer is obvious: the stock exchange .

The industry is constantly changing, but the only constant is that exchanges are always printing money.

2017 marked the first truly global bull market in the history of crypto.

The threshold for issuing tokens is extremely low. A white paper and a few PPT slides are all it takes to launch a project and raise funds. Investors frantically chase after "ten-fold or hundred-fold tokens." Countless tokens are launched and then go to zero. Most projects are frozen or delisted within 1-2 years, and even the founding teams disappear from the timeline.

However, listing a project requires a fee, user transactions require a fee, and futures contracts are charged based on the position size.

Cryptocurrency prices can plummet by half or even more, but exchanges only need to focus on trading volume to make money; the more frequent the trading and the more volatile the market, the more they earn.

In the DeFi boom of 2020, Uniswap challenged the traditional order book with its AMM model, and various mining, lending, and liquidity pools made people feel that "centralized exchanges are no longer needed."

However, the reality is very delicate. A large amount of funds are withdrawn from CEXs to on-chain mining, and then returned to CEXs for risk control, cashing out, and hedging during peak periods and crashes.

In terms of narrative, DeFi is the future, but CEXs remain the preferred entry point for deposits, withdrawals, hedging, and perpetual contract trading.

By 2024–2025, Bitcoin ETFs, the Solana ecosystem, and Meme 2.0 will once again push crypto to new heights.

In this cycle, regardless of whether the narrative changes to "institutional entry" or "on-chain paradise," one fact remains unchanged: a large amount of funds seeking leverage are still flowing into centralized exchanges; leverage, futures, options, perpetual contracts, and various structured products constitute the "profit moat" of exchanges.

In addition, CEXs are also integrating with DEXs at the product level, making it common to trade on-chain assets within CEXs.

Cryptocurrency prices may fluctuate, projects may change, regulations may tighten, and sectors may shift, but as long as people continue to trade and volatility persists, exchanges are the most stable "shovel sellers" in this game.

Besides exchanges, there are many other "shovel sellers" in the crypto world:

For example, mining machine companies like Bitmain profit by selling mining machines rather than mining, allowing them to remain profitable through multiple bull and bear market cycles.

Companies like Infura and Alchemy provide API services and benefit from the growth of blockchain applications;

Stablecoin issuers such as Tether and Circle earn "seigniorage from digital dollars" through interest rate differentials and asset allocation;

Asset issuance platforms like Pump.Fun continuously levy taxes by issuing meme assets in bulk.

...

In these positions, they don't need to bet correctly every time which chain will win or which meme will explode, but as long as speculation and liquidity exist, they can print money steadily.

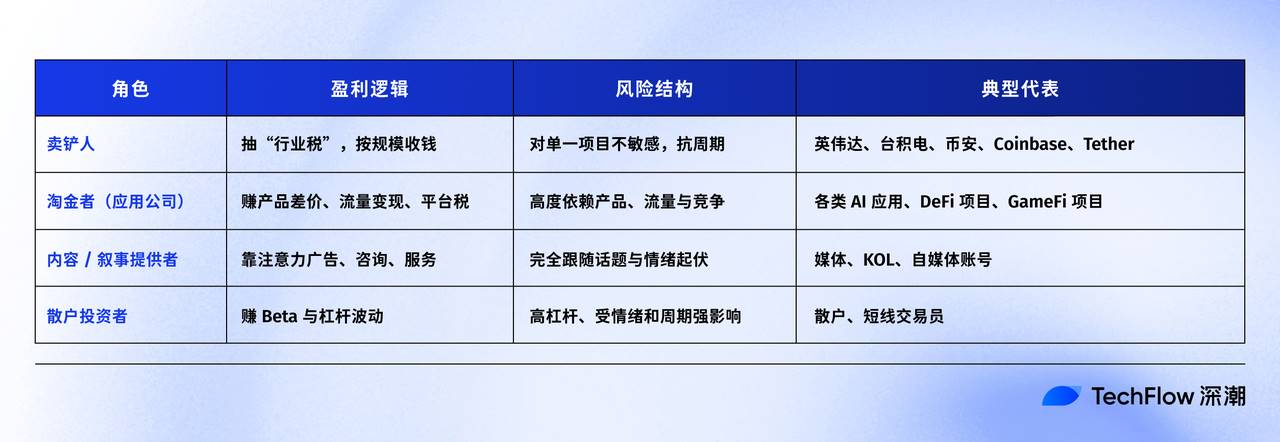

Why is "selling shovels" the most brilliant business model?

The real business world is far more brutal than people imagine. Innovation is often a matter of life and death, and success requires not only personal effort but also the passage of time.

For any cyclical industry, the result is often as follows:

Developing upper-level applications is like mining for gold, pursuing Alpha (excess returns). You need to bet on the right direction, the right timing, and beat your opponents. The win rate is extremely low, the odds are extremely high, and a slight misjudgment could result in losing everything.

Those who build the underlying infrastructure, essentially the upstream shovel sellers, earn in the Beta. As long as the industry continues to grow and the number of players continues to increase, they can reap the benefits of scale and network effects. Shovel sellers are in a business of probability, not luck.

Nvidia doesn't need to choose which AI model can "run out," and Binance doesn't need to judge which narrative will last the longest.

They only need one condition: "Everyone continues to play this game."

Moreover, once you get used to NVIDIA's CUDA ecosystem, the migration cost is unimaginably high. Once your assets are all on a large exchange and you're used to its depth and liquidity, it's very difficult to adapt to a small exchange.

The ultimate outcome of the shovel-selling business is often a monopoly. Once a monopoly is formed, the pricing power is entirely in the hands of the shovel seller, as evidenced by Nvidia's gross profit margin of up to 73%.

To summarize from a very blunt perspective:

Companies that sell shovels earn "industry existence tax," while gold mining companies profit from "time window dividends"—they must seize users' minds within a short window of opportunity, or they will be abandoned. People who create content or narratives earn "money from fluctuating attention"—once the trend shifts, the traffic evaporates immediately.

To put it more bluntly:

Selling shovels is a bet that "this era will move in this direction";

Developing an app is like betting that "everyone will only choose my app."

The former is a macro-level proposition, while the latter is a brutal elimination round. Therefore, from a probability perspective, the odds of winning by selling a shovel are an order of magnitude higher.

For retail investors and entrepreneurs like myself, this is also a profound lesson: If you can't see who the ultimate winner will be, or you don't know which asset will continue to rise several times over, then invest in the person who delivers water to all the miners, sells shovels, or even just sells jeans.

Finally, here's another statistic: Ctrip's Q3 net profit was 19.919 billion yuan, surpassing Moutai (19.2 billion yuan) and Xiaomi (11.3 billion yuan).

Don't just focus on who shines the brightest in the story.

Think about who can consistently charge for all their stories.

In a frenzied era, serving the frenzy while remaining calm is the highest wisdom in business.