This post was produced as the result of a PhD internship at Nethermind. Many thanks are owed to the Nethermind Research team, especially Conor McMenamin and Lin Oshitani, for providing helpful feedback on multiple drafts.

I. State Locks: Introduction.

When a proposer issues a state lock they promise that a user’s transaction will have access to one or more storage slots at the exact values the user specifies. Typically these will be the values which the slots held at the end of the previous block. The proposer then arranges the sequence of transactions to ensure that the user’s transaction sees the promised storage slot values. Intuitively, a state lock can be compared to a Top-of-Block transaction. The first transaction sees states that are as yet untouched by any other transaction in the block. State locks grant a similar privilege by allowing users to request that their transaction see the values which certain storage slots held at the end of the previous block, effectively securing first-rights access to untouched state. Unlike ToB transactions, however, state locks make it possible for multiple transactions to have first-rights access to disjoint parts of state within the same block.

II. Expected Logical Progression of a State Lock.

Step 1) User sends a state lock request to the proposer specifying a state snapshot, S.

- S is specified as a set of storage locations, L1…LN, and their corresponding values, V1…VN.

- The request will specify both a preTip and a postPayment.

Step 2) Proposer signs the request and returns it to the user, thereby promising that a future transaction from the user will execute against S.

- The proposer will now receive at least the preTip.

Step 3) User receives confirmation that S is locked.

Step 4) User sends a follow-up transaction, T, at some point before a deadline (expiry).

Step 5) Proposer receives T and orders the list of transactions so that T is the first to touch S.

- Before publishing the block, the proposer simulates the user’s transaction to ensure that it only touches S. If the transaction goes “out-of-bounds” by writing to a storage location outside of S, the proposer submits a proof to the user and a NullificationContract (see Appendix A) and is no longer subject to slashing for failing to include T.

Step 6) Proposer receives the postPayment for executing T against S.

- And still receives the postPayment if T reverts. Successful execution is not part of the promise.

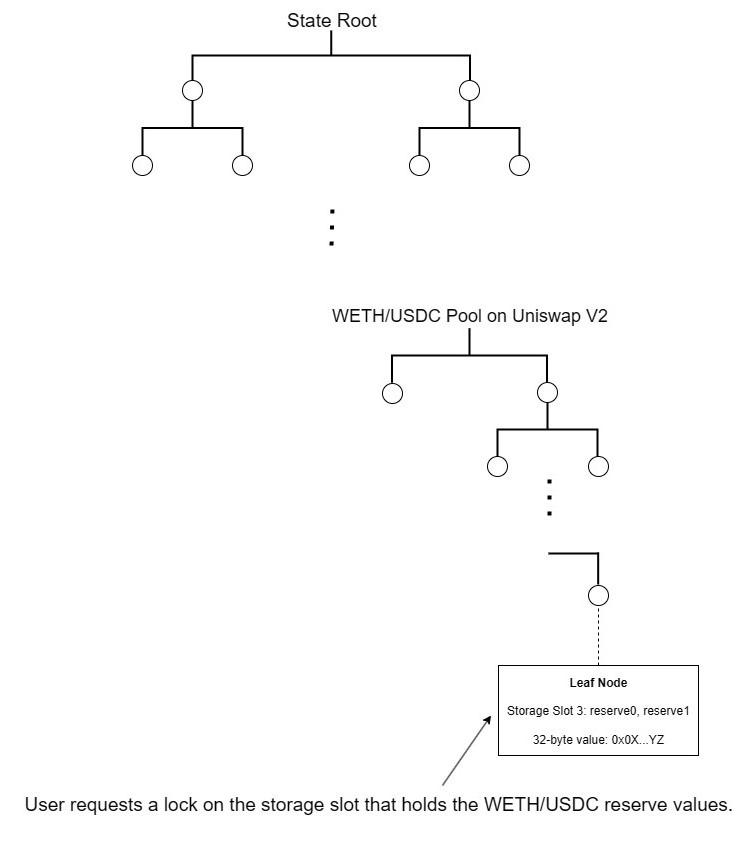

III. Visualization.

IV. Clarifications.

1. This proposal heuristically assumes that the current L1 block proposer is the sole handler of state lock requests/grants, but it allows that the proposer may delegate their authority to a sophisticated third party such as a gateway or a relay.

2. Since the proposer can grant multiple state locks for the same block, there is a risk that follow-up transactions may unexpectedly go "out-of-bounds” and accidentally overlap. Appendix A discusses the problem of accidental overlap along with some mitigation strategies.

3. It is expected that enforcement of state locks will involve slashing for misbehavior (e.g., the proposer receives the follow-up transaction but fails to include it).

4. State locks don’t include post-execution guarantees.

5. The proposer only collects either the preTip (if no follow-up is received) or the postPayment, not both. Mutual exclusion can be achieved by, e.g., signing the preTip and the postPayment using the same nonce.

6. The user is not required to send a follow-up transaction.

V. Use Cases.

1. Core use case: democratizing Top-of-Block access.

The core use case for state locks is to allow multiple users to have guaranteed access to untouched state within the same block. At present, getting access to untouched state means bidding for Top-of-Block (ToB) inclusion. By virtue of being first in line, a ToB transaction enjoys a de facto state lock on the entire state trie. This winner-take-all format is suboptimal for a number of reasons, one of which we have already noted: only one transaction per block is guaranteed access to untouched state.

Another is that whoever wins ToB inclusion is likely paying for more than they really need. A transaction may only need access to a specific pool, but the user pays to effectively lock the state root. And for all that overpaying, they still don’t get a slashable guarantee of ToB inclusion. The winning bidder pays and waits like everyone else to see where their transaction lands.

State locks fundamentally alter these dynamics: users have more options than just ToB inclusion, any number of users can have first-access rights, each user can bid on just those parts of state in which they are interested, and users receive a slashable promise that the relevant parts of state have been locked.

2. Two concrete examples stemming from the core use case.

Since state locks function to secure access to untouched state, their use cases will largely overlap with the reasons that users seek to get their transactions at the top of the block. While there are many such reasons or use cases, two in particular are worth highlighting.

2.1 New arbitrage strategies.

One of the main reasons for wanting to get a transaction at the top of the block is to secure an arbitrage opportunity. While the core use case for state locks is to make such opportunities more widely available, state locks also open up new trading strategies. One reason for this is that the follow-up transaction affords the user maximum optionality. In a standard case of CEX-DEX arbitrage, the user is able to lock the DEX price and wait until just before the expiry to send the follow-up, adjusting their trade as needed to extract maximum value from price deviation. Alternatively, if prices converge unexpectedly, they can simply opt out by withholding the follow-up (although they must still pay the preTip), thereby potentially avoiding a loss.

2.2 Securing important trades for low-frequency users.

While state locks may be of interest primarily to sophisticated users, such as professional traders designing trading bots, they also have a unique use case for the typical low-frequency user who is sending what they would consider to be an especially important transaction. For a user who is making a large (for them) trade on a DEX or seeking priority access to an NFT mint, a state lock could provide invaluable assurance that their trade won’t fail or fall prey to front-running.

3. Preconfirmation use cases.

The state lock grant can be thought of as an inclusion preconfirmation vis-a-vis the follow-up transaction. In general, the primary use case for preconfirmations is improved user experience, especially in the context of based rollups. Considered as a type of preconfirmation, state locks fit this use case: state locks give users the assurance that their transaction will execute under the conditions specified in the snapshot. But they also have use cases stemming from their advantages over other types of preconfirmations.

3.1. Preconfirmations with stricter assurances than inclusion preconfirmations.

With an inclusion preconfirmation, all the user knows is that their transaction will end up in the block. With a state lock, the user knows their transaction will be included and they know the exact states it will see.

3.2. State locks carry less risk for the proposer/preconfer than execution preconfirmations.

In their strictest form, execution preconfirmations involve a commitment to a specific post-execution state root. Less strict variants involve weaker commitments to state diffs or user intents. Since the preconfer is on the hook for post-execution results, they necessarily take on ex ante risk stemming from imperfect modeling/simulation forecasts (e.g., faulty warm/cold assumptions, missed oracle updates, missed code paths), especially if the preconfer doesn’t have exclusive block building rights. By contrast, state locks avoid such risks by committing only to pre-execution conditions, effectively collapsing all ex ante risk into out-of-bounds risk.

At first glance, lowering proposer risk might seem to raise user risk. But the tradeoff is more nuanced: the proposer promises pre-state conditions and enforces them with out-of-bounds screening, while the user simulates the follow-up against the values specified in the snapshot. With sufficiently sophisticated tooling, the user can simulate execution results against the snapshot just as accurately as the proposer/preconfer. Unlike the preconfer, however, the user is not subject to slashing penalties for un-simulated results, only trading risk and gas fees. Thus, by shifting accountability from post-state outcomes to pre-state conditions, state locks can reduce proposer risk without substantially increasing user risk.

3.3. Preconfirmations that provide strong front-running protection for the user.

By locking state at the value it held at the end of the previous block, the user is assured that their transaction will be the first in the current block to touch the locked state. This makes front-running effectively impossible, as no other transaction can preempt the follow-up without violating the state lock.

4. Making transactions more gas-efficient.

Intuitively, locking the exact pre-execution state makes transaction behavior more predictable. As a result, transactions become more susceptible of optimization. One concrete illustration of how this might work comes from a study on EIP-2930 access list transactions.

An EIP-2930 transaction includes an access list of addresses and storage keys that are “warmed” at the beginning of execution so that accesses are charged at the warm access cost as specified in EIP-2929. According to the authors of the study, the gas-saving potential of transaction access lists (TALs) is primarily hampered by uncertainties regarding intra-block state:

“Our analysis reveals that for around 71% of all transactions [that] could profit from including an ideal TAL, the ideal TAL cannot be computed correctly on the state of the last block. Instead, it requires knowledge on the intra-block state the transaction executes on, which is not known ahead of time — making a proper TAL computation in these cases nearly impossible.” (p. 2)

By locking in the exact pre-execution state, state locks make it possible to compute an ideal TAL that includes all and only the storage keys that the transaction will access. Although the TAL can still be imperfect due to other kinds of errors, such as unnecessarily including default-warm addresses (e.g., the recipient), a perfect TAL that maximally optimizes gas usage requires knowing the precise pre-execution state.

5. Additional benefits: reduced mempool contention, lower reversion rates.

While MEV-Boost has dramatically reduced many of the negative externalities associated with priority gas auctions, such as bidding wars, spam-flooded mempools, and blocks clogged with failed transactions, state locks can still help to make block production more orderly and efficient by reducing mempool contention and lowering reversion rates.

5.1 Reducing mempool contention.

Flashbots currently enables block builders to expose API endpoints such as mev_simBundle, which allows searchers to simulate bundles against their most recent block template. By exposing a new proposer_getLockedStates endpoint, the proposer could share a real-time list of locked states, giving rational users the opportunity to self-censor, thereby reducing contention in the public mempool. This design choice, however, may come with privacy concerns, since it requires exposing information (e.g., potential arbitrage targets) pertaining to unpublished transactions.

5.2 Lowering reversion rates.

By knowing the exact pre-execution state, wallets, dApps, and sophisticated users will be able to simulate transactions with a higher degree of accuracy, helping to prevent transaction reversion due to things like insufficient gas limits, stale reserve values, and external call failures.

VI. Key Terms.

Accidental overlap: accidental overlap occurs when a transaction has unauthorized access to some part of state that is reserved by a state lock grant.

- See Appendix A for discussion.

Domain: An addressable storage location in the EVM’s persistent state, specified as the set {A, K} where A is a contract address and K is a 32-byte storage slot (key).

Domain-value pair: the pair of a domain, {A, K}, and a value, V, specified as {{A, K}, V}}.

- Concrete illustration using the WETH/USDC pool on Uniswap V2:

- Block height: 22385280

- Domain: {0xB4e16d0168e52d35CaCD2c6185b44281Ec28C9Dc, 0x…03}

- Value: {0x66304740000000000000000008d9350c2aac000000000124394c1432cced5400}

- Domain-value pair: {{0xB4e16d0168e52d35CaCD2c6185b44281Ec28C9Dc,0x…03}, 0x66304740000000000000000008d9350c2aac000000000124394c1432cced5400}

Expiry: the deadline for enforcing inclusion of the follow-up transaction.

- The expiry sets a deadline for when the follow-up transaction must be received in order for the proposer to be slashed for not including it. If the follow-up arrives after the expiry, the proposer is not slashed for failing to include it.

Follow-up transaction: a transaction sent pursuant to a state lock grant.

- If a user sends multiple transactions for inclusion within the same block and one of them is the follow-up transaction for a state lock, the follow-up transaction will be determined by a match between the transaction’s nonce and the nonce specified in the state lock request.

Out-of-bounds access: when a follow-up transaction writes to a domain that was not specified in the state lock request.

Permission set: the set of domains to which the follow-up transaction requires access, taken from the snapshot.

Example where A is a contract address, K is a storage slot, and V is the value at which K is reserved:

- Snapshot: {{{A1, K1}, V1}}, {{A2, K2}, V2}}}

- Permission set: {{A1, K1}, {A2, K2}}

Intuitively, the number of elements in the permission can be used to count or measure "how much” state gets locked.

postPayment: the priority fee for fulfilling the state lock.

The value of the postPayment is calculated to include the preTip. The postPayment is effectively the “full” priority fee:

postPayment = preTip + compensation for including the follow-up transaction

The follow-up transaction authorizes the proposer to collect the postPayment.

preTip: a fallback payment to the proposer that is included with the state lock request.

The preTip compensates the proposer in the event that (a) the user fails to send a follow-up transaction or (b) the follow-up transaction goes out-of-bounds by writing to a domain outside of its snapshot (see Appendix A).

The state lock request authorizes the proposer to collect the preTip.

The preTip and the postPayment must be made mutually exclusive by, e.g., signing each with the same nonce.

Snapshot: the set of all domain-value pairs specified by a state lock request.

- Schematized examples:

- Single address, single storage slot: {{A, K}, V}

- Single address, multiple storage slots: {{{A1, K1}, V1}, {{A1, K2}, V2}}}

- Multiple addresses, single storage slot per address: {{{A1, K1}, V1}, {{A2, K2}, V2}}}

State lock: a slashable commitment to ensure that a transaction executes against a set of states specified by a snapshot.

- Note: The concept of locking state does not, in itself, contain the concept of executing a transaction against the locked state. A user could request a state lock for nefarious purposes, such as preventing others from transacting. Nonetheless, our usage is stipulative: according to our meaning, a “state lock” implies a commitment to execute a transaction against the locked state.

State lock request: a signed message that requests a state lock.

- The state lock request will specify (i) the snapshot, (ii) the preTip, (iii) the postPayment, (iv) the nonce of the follow-up (v) the block in which the follow-up transaction is to be included, and (vi) the expiry. The user will sign using a standard like EIP-712.

{

blockNumber:…,

snapShot:[(A1, K), (V1)…],

preTip:…,

postPayment:…,

expiry:…,

nonce:…,

}

State lock grant: a signed message that issues a state lock.

VII. Fair Exchange.

The Follow-Up Problem.

The core of the Follow-Up Problem is that a proposer may grant a user’s state lock request and proceed to ignore their follow-up transaction, thereby failing to honor their commitment. It’s important to clarify that the Follow-Up Problem is not the same as the problem of timely fair exchange for preconfirmations. Preconfirmations improve UX by having the preconfer send a binding, timely preconfirmation to the user. Fair exchange is therefore violated if the preconfirmation is not issued in a timely fashion. The core logistical question is to ensure timely issuance given the economic incentives to delay. By contrast, the Follow-Up Problem is not about ensuring timeliness. Instead, the core logistical challenge is to ensure that the proposer honors their commitment to include the user’s follow-up transaction (assuming they receive it in time).

Q: Why would the proposer ignore follow-up transactions and forfeit the postPayment?

(A1) They may have received a higher bid for a colliding transaction.

(A2) They may be indiscriminately granting state lock requests in order to collect as many preTips as possible.

This strategy naturally pairs including only the follow-ups that offer the largest postPayments.

(A3) The proposer may simply be censoring the user.

Mitigation strategies.

(S-1) Splitting the tip into pre and post payments already provides some protection to the user. (The idea of using a two-part tip is borrowed from Luban’s solution to the Fair Exchange Problem within its system of proposer commitments.)

The smaller the preTip, the lower the risk for the user. But there is a corresponding increase in risk for the proposer. Users may promise large postPayments but fail to send follow-up transactions, which could lead to opportunity costs for proposers. Fair exchange remains a two-way street.

(S-2) The proposer is only allowed to grant one state lock per domain, i.e., per {A, S} pair. The proposer remains free to include non-state lock transactions (including preconfirmations) that execute against a locked domain so long as they do so after the domain is no longer locked, i.e., after the follow-up transaction.

Enforcement could take the form of a smart contract that slashes the proposer for issuing more than one state lock per domain.

Pro: Since the proposer cannot grant additional locks on the domain, there is no incentive to issue bids indiscriminately or accept a competing state lock request with a higher tip.

Con: There is still the possibility that the proposer will ignore the user’s follow-up transactions in order to (a) censor the user or (b) take a higher bid for a non-state lock transaction.

(S-3) Treat state locks as rights of exclusive access: only the user’s follow-up transaction has a right to modify the domains in its permission set, P. No other transaction in the block may write to any domain (as the pair of an address and a storage key {A, K}) that is in P.

Pro: Protects the user against (i) being outbid and (ii) indiscriminate issuance to maximize preTips.

Con 1: This protection comes at the cost of restricting the proposer’s ability to include additional transactions that execute against P.

Con 2: Exclusive access could make the request considerably more expensive.

Con 3: The proposer can still engage in censorship by ignoring follow-up transactions.

This is a consistent theme: protecting against pure censorship is difficult.

(S-4) Transaction attestation committee.

Another option is to send the follow-up transaction to both the proposer and an attestation committee. Each member of the committee logs the time at which they received the follow-up transaction and gossips it to other members. If a sufficient percentage of the committee attests to observing the follow-up transaction before the end of the expiry, the proposer can be slashed for not including it.

(S-5) Routing through a trusted intermediary.

The main benefit of using a trusted intermediary instead of a committee is that there is no need for attestations to propagate across the network. This would give users more time to delay before sending the follow-up transaction. The main downsides are centralization and introduction of an additional trust element.

(S-6) Reputation scores (reputational “slashing”) for proposers recorded in an on-chain registry.

In the simplest case, a registry could be used to record raw data about proposer performance, such as the number/percentage of missed follow-up transactions, which does not strictly imply malicious behavior. Despite this limitation, the registry would at least provide some basis for risk assessment. Users may wish to avoid proposers (or gateways) with a higher propensity to miss follow-up transactions, regardless of fault. The registry could also be used to impose minimum reliability requirements.

Timeliness.

State locks incentivize timely fair exchange by splitting the priority fee into a preTip and a postPayment and conditioning the latter upon inclusion of the follow-up transaction. Ceteris paribus, the sooner the user receives the signed state lock grant, the greater the potential value of the follow-up. Delaying issuance of the state lock grant therefore risks loss of value for the user. If the follow-up loses enough value, the user may decide not to send it, and the proposer may lose out on the postPayment. By contrast, the sooner the user receives the state lock grant, the more likely they are to send the follow-up transaction due to its greater potential value. Thus, timely issuance of the state lock grant maximizes value for both the user and the proposer.

Ghost Grants.

In the event that either (a) the user fails to send the follow-up transaction or (b) the follow-up goes out-of-bounds (see Appendix A), the state lock request authorizes the proposer to collect the preTip (though the intended design is for the preTip to be replaced/paid by the postPayment). While this reduces risk for the proposer, it introduces a new avenue for denying fair exchange to the user. Since the state lock request authorizes payment of the preTip, a malicious proposer can collect the preTip without issuing a state lock grant that commits them to including the user’s follow-up transaction. Since fair exchange is violated if the user pays for a “ghost” grant that was never sent, the core logistical challenge is to ensure that proposers do not collect preTips for “ghost” grants.

The user may elect to take their chances by sending the follow-up transaction without first receiving a grant, but doing so is both risky and unfair, as even in the best-case scenario they pay the postPayment for a state lock that was never issued. The more rational choice is to withhold the follow-up or submit a regular transaction. As such, although sending the follow-up without the state lock grant is technically an option, doing so doesn’t help to ensure fair exchange.

A better option is to utilize third-party attestation by having the proposer send the state lock grant to both the user and an attestation committee or a trusted intermediary. The user could then prove that fair exchange was violated by submitting a missingGrantWitness signed by the third party to a refundContract that allows them to clawback the preTip and slash the proposer. An alternative design would be to require the proposer to prove timely sending of the state lock grant in order to collect the preTip. The collection would need to include both the grant and a signed sentGrantWitness from the third party attesting to timely issuance. Since the state lock request would no longer authorize collection of the preTip, it must be paid in some other way. One possibility is to have the user make a deposit into a preTipPayment contract. The proposer can then collect the preTip by submitting the grant and the sentGrantWitness to a preTipPayment contract.

Appendices.

The following appendices continue to assume that: (i) the current L1 proposer (or their delegate, such as a gateway) is the sole handler of state lock requests/grants and (ii) state lock grants pertain to a set of domains defined over address/storage slot pairs in the L1 state trie for the current block. This is a scoping assumption made to prioritize simplicity and clarity while admittedly sacrificing breadth. As such, although state locks can be considered a type of preconfirmation, many details may not transfer directly over to an L2 variant (e.g., our definition of “accidental overlap” relies on EVM opcode semantics).

Appendix A: The Problem of Accidental Overlap

State locks make it possible for multiple transactions to have first-rights access to non-overlapping parts of state. But this novel functionality introduces additional risk for the proposer. Since the user doesn’t include the follow-up transaction with the state lock request, the proposer cannot screen out roaming transactions. They must grant state locks “blindly.” If one follow-up transaction unexpectedly touches some part of state that is reserved for a different transaction (i.e., accidentally overlaps it), the proposer may face slashing penalties.

Clarifying “Out-of-Bounds” and “Accidental Overlap”.

An out-of-bounds access is best defined as any write (SSTORE) to a domain that is not in a transaction’s permission set. Overlapping reads (SLOAD, BALANCE, external CALL to view functions) don’t alter state and therefore can be considered harmless overlap. By defining “out-of-bounds” accesses in this way, things like overlapping oracle lookups don’t count as out-of-bounds.

Out-of-Bounds Access: An out-of-bounds access occurs when a state lock transaction, T, writes to some domain, {A, K}, that is not in its permission set, P.

Accidental Overlap: A transaction, T1, accidentally overlaps another transaction, T2, when T1 executes before T2 and T1 writes to some domain, {A, K}, in the permission set of T2.

Preventing Accidental Overlap.

Regular transactions can accidentally overlap with state lock transactions. The most straightforward way to prevent this from happening is to prioritize sequencing for state lock transactions. But accidental overlap among state locks is not so easily addressed. The remainder of this appendix discusses some strategies for mitigating against it.

Minimization Strategy 1: EVM-Based Permission Guard.

One way to mitigate against accidental overlap is to use an in-EVM permission guard that “forces” follow-ups to stay in their lanes by reverting those that make out-of-bounds write attempts. While something like a native precompile could be used to enforce the permission set directly in the EVM, this is not practical on mainnet today. Introducing a new precompile address would require a formal EIP, a protocol-level hard fork, coordinated Eth client implementations, audits, and ecosystem tooling. In general, the development, testing, and social coordination overhead make an EVM-based approach infeasible in the near term.

Minimization Strategy 2: Off-Chain Simulation.

Another option is to have the proposer simulate follow-up transactions off-chain. If the proposer detects an accidental overlap, they could produce an out-of-bounds proof and send it to the user, ideally leaving enough time to revise the follow-up. The proposer would also need time to re-simulate. In order to accommodate the back-and-forth, the expiry should be set earlier in the slot and a second expiry will be needed. If the user fails to return a “fixed” follow-up transaction prior to the second expiry, the out-of-bounds proof can be sent to a NullificationContract.

Problems with Off-Chain Simulations.

While more feasible than a native precompile, this approach is not without its challenges. First, the proposer must be able to produce a satisfactory out-of-bounds proof without exposing the list of transactions to the user. There are cases where this is possible, such as a swap with an unnecessary leg, but these are more likely the exception than the rule. Second, it will be difficult to ensure fair exchange for the revised follow-up transaction due to the limited timeframe. Third, the NullificationContract will need to handle disputes between the proposer and the user over the out-of-bounds proof.

Some Potential/Partial Solutions.

The challenges facing an off-chain simulation strategy are not insubstantial, but they can be made less daunting by adopting the following:

1. Make follow-up transactions final.

Considering the follow-up transaction final and un-revisable eliminates the timing issues related to revising and re-simulating. With no need for revising/resimulating, an out-of-bounds proof can be submitted after the block is published, which eliminates the need for a second expiry along with any privacy concerns about exposing unpublished transactions. The main downside is reduced optionality for the user.

2. Define best practices.

A set of “best practice” guidelines for users and proposers could be instrumental in reducing accidental overlap. One possibility could be to provide a recommended number of domains in the permission sets for common transaction types. To use a toy example, suppose that the vast majority of simple swaps require permission sets with 2-4 domains. Users could then infer that having more than four domains for a simple swap increases the risk of accidental overlap (or, more likely, tooling would be designed around best practice recommendations).

Appendix B: The Up-Front Model.

The follow-up transaction maximizes optionality for the user at the cost of introducing design challenges related to the Follow-Up Problem and the prevention of accidental overlap. These challenges can be largely sidestepped, however, by having the user include their transaction as part of their state lock request and by considering the transaction to be final and unrevisable. The main downsides of such a design include reduced optionality and higher susceptibility to MEV extraction. On the whole, it is a more proposer-friendly model. But the gains in design simplicity make it worth briefly exploring.

Expected Logical Progression within the Up-Front Model.

Step 1) User sends a state lock request that includes (i) a snapshot, (ii) a transaction, and (iii) a priority fee.

Step 2) Proposer receives the request and, if the priority fee is priced appropriately, simulates the transaction.

Step 3) Proposer returns a confirmation message signing the user’s request.

Step 4) Proposer locks the transaction into their block template/broadcasts the updated state to the network.

Step 5) User receives the confirmation message, which can be used to slash the proposer in the event that, e.g., the user’s transaction executes against the wrong snapshot.

Adding the Transaction to the State Lock Request.

The state lock grant now only uses a single Tip field, has no expiry, and must include an additional txPayload field:

{

blockNumber:…,

snapShot:[(address, storage slot), (value)…],

Tip:…,

nonce:…,

txPayload:…,

}

General Advantages of the Up-Front Model.

1. Simpler design with fewer moving parts.

The problems of fair exchange associated with the follow-up transaction are eliminated along with the mechanisms required to address them, such as an attestation committee and an expiry.

2. Proposers can screen for out-of-bounds accesses before granting a state lock.

Advantages for the Proposer.

1. With the user’s intent made explicit, the proposer can better map the space of MEV opportunities.

2. The proposer can more readily offer sequential state locks against the same domain within the same block.

3. A single tip means users can’t avoid paying the postPayment/full priority fee by withholding the follow-up.

4. Having just one tip may mean a simpler pricing model.

Disadvantages for the proposer.

1. Reduced optionality may lower the value of state locks for users and lead to lower priority fees for proposers.

Advantages for the User.

1. Better tip pricing: assuming that reduced optionality and increased exposure to MEV lower the value of a state lock, the expected corollary is lower priority fees.

2. Complications related to the follow-up transaction are eliminated: timing, disputes, etc.

3. If sequential state locks can be made to work, users have more options.

Disadvantages for the User.

1. No follow-up transaction means less optionality.

2. Users are more exposed to MEV exploits.

3. Step 4 involves exposing information about unpublished transactions, which may raise privacy concerns.

Appendix C: State Lock Fraud and L1 ZK Research

One of the main differences between state locks and other types of proposer commitments is that state locks focus on pre-execution conditions rather than post-execution results. This means that, somewhat counterintuitively, state lock fraud is entirely a matter of what happens before the follow-up transaction executes. As such, the first half of this appendix attempts to clarify the nature of state lock fraud by canvassing a few preliminary definitions. The second half then goes on to consider some ways in which current L1 zkEVM research can be served by conducting further research on state lock fraud proofs.

Two Definitions of State Lock Fraud.

There are basically two different ways to think about state lock fraud. The first is to think in terms of “snapshot fraud”. The second is to focus on “first-access fraud”. These two kinds of fraud reflect two different ways of understanding the state lock grant.

On the second and stricter interpretation, the state lock grant promises that the user’s follow-up transaction, T, will be first in line to write to any of the domains specified in T’s permission set, P. For clarity, T is said to be “first in line” or to have a “right of first access.” If T reverts and a later transaction is the first to write to some domain in P, the “first in line” promise is still honored so long as no earlier transaction writes to one of T’s domains. Put succinctly, our preliminary definition says:

First Access Fraud. First-access fraud occurs if any transaction preemptively writes to a domain reserved by a state lock transaction.

On the first and slightly less strict interpretation of the state lock grant, there is no first-access promise. The promise is that T will execute against a set of domain-value pairs as specified by T’s snapshot, S. Snapshot fraud occurs if T executes against the pre-T state root, Rpre, and Rpre does not contain S (i.e., fails to include some domain-value pair specified by S).

The distinction between first-access fraud and snapshot fraud is more than just conceptual. It has practical consequences when it comes to proving fraud. As a preliminary definition:

Snapshot Fraud. Snapshot fraud occurs if for some state lock transaction, T, domain, D, and 32-byte value, V, the snapshot for T specifies that D maps to V in the pre-T state root, Rpre, and Rpre is such that D maps to some value, V*, where V* ≠ V.

In order to prove snapshot fraud, we must first derive the pre-T root against which T executed, Rpre. A Merkle inclusion proof can then be used to show that D maps to V* under Rpre (e.g., by using an account-level MPT path to the storageRoot and then an MPT path to D(V*) under the storageRoot). Showing that D maps to V* under Rpre establishes that T actually saw D(V*). The last step is then to show that V* ≠ V, where V is taken from the signed state lock grant.

In order to prove first-access fraud, what must be shown is that some other transaction, T*, executed before T and wrote to one of T’s domains. This can be done by proving the relative position of T* and T in the block’s transactionsRoot trie and by re-executing up to the step in the execution trace at which T* wrote to some domain in T’s permission set. In contrast to snapshot fraud, there is no need to derive the Rpre against which T executed. If T is the 10th transaction and T* is the 2nd, a proof of first-access fraud will require fewer steps than a proof of snapshot fraud – which must derive the results of every transaction before T.

Our brief discussion of state lock fraud necessarily leaves out many details. For example, if T* writes the same value (no-op SSTORE) to one of T’s domains, then first-access fraud occurs but snapshot fraud doesn’t. That might be a reason to require that both forms of fraud occur before penalties are assessed (or for defining first-access fraud in terms of “modifying” rather than “writing to” a reserved domain). Regardless, our purpose is simply to get clear on the basic conceptual model of state lock fraud.

How State Lock Fraud Proofs Can Serve L1 ZK Research.

The Ethereum Foundation believes that the best path forward for Ethereum is to ultimately become ZK-based “at all levels of the stack.” Against that backdrop, it’s worth noting how state lock research could support those goals. In the remainder, we will consider how state lock disputes could be resolved through a ZK-based design where an execution trace is re-executed off-chain and a succinct proof is verified on-chain, thereby avoiding the prohibitive cost of in-protocol re-execution (although BALs have the potential to make it significantly more cost-effective to handle disputes on-chain).

State lock fraud proofs have the potential to create unique research opportunities. Ex hypothesi, a state lock fraud proof will never need to re-execute anything beyond the last state lock transaction. On the plausible assumption that proposers prioritize sequencing for state lock transactions (i.e., that proposers put them at the top of the block), a fraud proof would only need to handle a fraction of the full block. By contrast, systems like Succinct Labs’ SP1 Hypercube target full L1 blocks, typically by producing sub-block proofs and then aggregating them. If proposers put state lock transactions at the top of the block, disputes will only need to prove an early slice or “prefix” rather than the whole block, making the fraud proof circuits materially smaller than a full L1 zkEVM proof.

To illustrate, consider the first-access fraud example from earlier. If the out-of-bounds transaction, T*, is the second transaction in the block, then the circuit only re-executes two transactions and reconstructs the pre-T* intermediate root inside the witness. More generally, if T* is the *i-*th transaction, then the first-access fraud proof circuit re-executes i transactions and reconstructs i-1 intermediate roots. Put in full-block zkEVM terms, a first-access fraud proof would be comparable to proving a small single prefix rather than the full block, since there’s no need for recursive aggregation/composition over multiple prefixes. In a similar vein, while a snapshot fraud proof would typically require more constraints than a first-access fraud proof, the size of the circuit is still on the order of a single-prefix proof.

Due to their small and focused circuits, state-lock fraud proofs may present a practical opportunity to research novel gadget-level optimizations. One idea would be to prototype a circuit that batches the same Keccak round across many independent hashes (e.g., RLP-encoded MPT nodes, storage key derivations) so that the prover executes one “wider” step in place of many “narrower” ones. State locks are a natural fit for this kind of round “fusing” or round batching: since out-of-bounds screening removes dependencies, state locks already enforce the independence needed to run many hashes in parallel without violating EVM order. The payoff is fewer circuit rows/steps, which can reduce proving time and may also trim proof size. Although admittedly speculative, hash round “fusing” is one example of a concrete optimization that state lock circuits can test/validate with results that carry over to L1 hashing hot-spots.

State lock fraud proofs may also be able to serve as a kind of “test lab” for measuring proving efficiency and generating useful empirical data. Due to the short “prefix” and a relatively tiny set of touched slots, the circuit is simple enough to expose component costs such as time per opened slot, witness bytes per MPT path, etc. In full-block proving, those signals tend to get blended together with other data (e.g., EC/KZG math, witness I/O, and aggregation), making it harder to recover clean per-component numbers. In addition, state lock fraud proofs may be small enough to run on “home” prover hardware and allow for the collection of value empirical data on, e.g., energy/RAM/GPU profiles for “home” provers. In this way, state lock fraud proof research may be able to complement full-block benchmarking by providing fine-grained, component-level measurements that can be estimated using small proofs and extrapolated back to the relevant full-block workload distributions (e.g., SSTORE/SLOAD openings).

One caveat here is that the risk of slashing should make state lock fraud exceedingly rare. Even so, it doesn’t necessarily follow that fraud proofs will be rarely requested. From the user’s perspective, unexpected transaction behavior is the primary trigger for a fraud request. Given that state locks only promise pre-execution conditions, not results, unexpected behavior may not be uncommon. Assuming that actual fraud is much less common than suspected fraud, most fraud proofs will serve the opposite of their nominal purpose: they will serve as “honesty” proofs which confirm that no fraud was committed. In fact, proposers would have an incentive to provide such “honesty” proofs upon request, especially if they can be unofficially verified off-chain by a third party. The need to provide timely and efficient “honesty” proofs would naturally create incentives for research and optimization.

In closing, it’s worth noting that the potential benefits to L1 ZK research suggested here are not unique to state locks. Any execution preconfirmation protocol that requires fraud proofs that prove execution context/results will be in a position to take advantage and potentially advance the state of L1 ZK research.