01 Introduction

The cross-border liquidity of blockchain and crypto assets has presented regulators in various countries with the challenge of balancing the encouragement of financial innovation with the prevention of systemic risks. Against this backdrop, different jurisdictions have gradually drawn up several inviolable "regulatory red lines" to regulate public blockchain asset trading activities and protect investors' rights. For example, anti-money laundering (AML) and customer identification (KYC) requirements have become almost a global consensus, and most major jurisdictions have included virtual asset service providers (VASPs) in the anti-money laundering legal framework [1]. Furthermore, the independent custody and segregation of customer assets by trading platforms to ensure that customer assets are not harmed by third-party creditors in the event of bankruptcy is also regarded as a regulatory bottom line requirement. In addition, preventing market manipulation, curbing insider trading, and avoiding conflicts of interest between trading platforms and related parties have become common goals of regulatory agencies in various countries to maintain market integrity and investor confidence [2][3].

Despite regulatory convergence in the aforementioned key areas, there are significant differences among jurisdictions on certain emerging issues. Stablecoin regulation is a prime example: some countries restrict stablecoin issuance to licensed banks and other institutions and impose strict reserve requirements, while others are still in the legislative exploration stage [4][5]. In terms of crypto derivatives, a few jurisdictions (such as the UK) directly prohibit the sale of such high-risk products to retail investors [6]; while other countries regulate trading through licensing systems and leverage restrictions. The legal status of privacy coins (anonymous cryptocurrencies) also varies greatly: some countries explicitly prohibit exchanges from supporting privacy coin trading, while other regions have not yet legislated against it but indirectly suppress the circulation of privacy coins through strict compliance requirements [7]. In addition, on the regulatory path of Real-World Assets (RWA) and Decentralized Finance (DeFi), jurisdictions have different attitudes: some actively establish sandbox trials and special regulations to govern such innovations, while others tend to incorporate them into the existing securities or financial regulatory framework for constraint.

To systematically analyze the above convergence and divergence, this paper selects representative jurisdictions such as the United States, the European Union/United Kingdom, and East Asia to conduct a cross-jurisdictional regulatory system comparison. Chapters 2 to 5 focus on specific issues of consensus on regulatory red lines and institutional divergence, respectively, and clarify the regulatory provisions of different jurisdictions by citing real law article numbers, official documents issued by regulatory agencies, and typical institutional practices or cases [2][8]. Chapter 6 summarizes the similarities and differences in regulatory experience of various jurisdictions and discusses the institutional implications and impact of this regulatory landscape on the global crypto asset market. The concluding section of the article puts forward thoughts on future international regulatory coordination and industry compliance development.

Based on the above research, this article aims to provide detailed information for crypto asset institutions and compliance researchers, helping them understand the bottom line and differences of regulatory "red lines" in various jurisdictions, thereby better managing compliance risks in cross-border operations. It also provides policymakers with a comparative perspective to explore possible paths for promoting regulatory coordination at the global level.

02 Consensus on Regulatory Red Lines: Fund Compliance and Asset Security

This chapter explores the two most consistent bottom lines in global regulation: anti-money laundering (KYC/AML) and segregation of customer assets. While the general direction is similar, there are still noteworthy differences in the specific implementation details.

2.1 Global Benchmarks for Customer Identification and Anti-Money Laundering (KYC/AML)

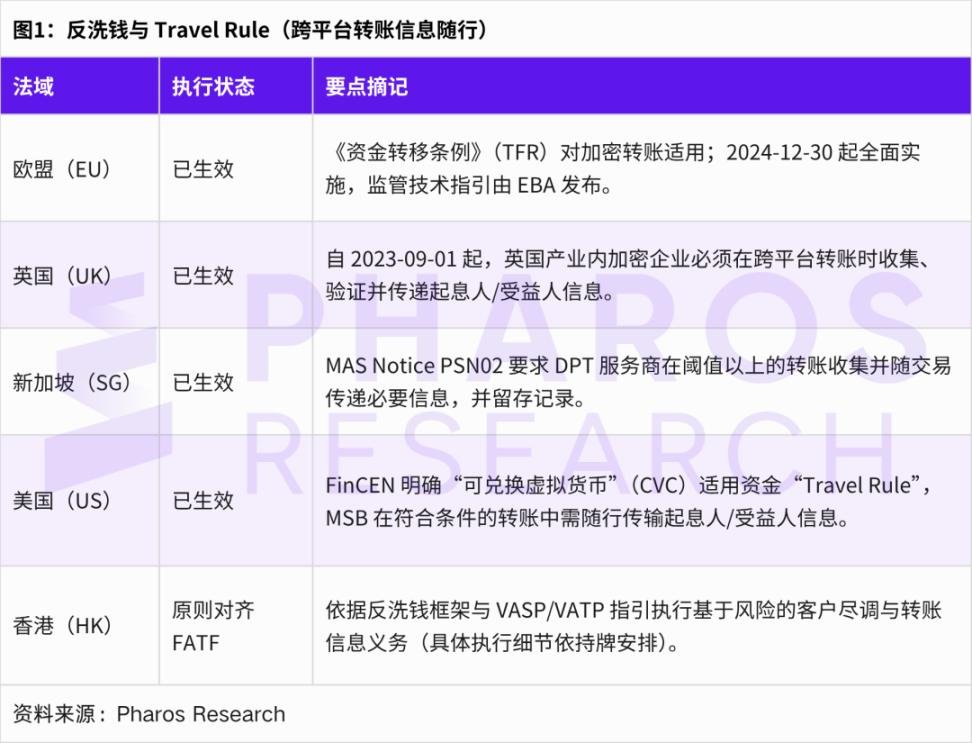

Since 2018, the requirement to fully extend anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT) to the crypto asset sector has become a global regulatory consensus. At the international level, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) revised Recommendation 15 in 2019, bringing virtual asset service providers (VASPs) under the same stringent AML/CFT obligations as traditional financial institutions[1]. The FATF also introduced the "Travel Rule," requiring VASPs to collect and transmit the identity information of the initiator and recipient of large crypto transactions to the other party[13]. This global standard has set a benchmark for domestic legislation in various countries. By 2025, most major jurisdictions have included VASPs in their national anti-money laundering regulatory systems and established systems such as customer due diligence (KYC) and suspicious transaction reporting. According to the latest FATF report, 99 jurisdictions worldwide have promulgated or promoted relevant regulations to implement the Travel Rule and enhance the transparency of cross-border virtual asset transactions[14].

In the United States, anti-money laundering obligations are primarily established by the Bank Secrecy Act (1970) and its supporting regulations. Since 2013, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) under the Treasury Department has explicitly identified most cryptocurrency trading platforms as "money services businesses" (MSBs), requiring them to register with FinCEN and comply with BSA regulations [2]. Specific requirements include: implementing written customer identification (CIP) procedures to collect and verify basic information such as name, address, and ID number; conducting customer due diligence (CDD) to identify the beneficial owners of corporate clients and understand the purpose of their transactions [15]; maintaining transaction records and reporting suspicious activity (SAR) to the authorities. In addition, the United States added tax reporting obligations for crypto transactions to the Infrastructure Act of 2021 and is considering legislation to strengthen the collection of information on transactions in non-custodial wallets. At the enforcement level, the U.S. authorities have filed lawsuits and imposed penalties on crypto companies that violate AML regulations on multiple occasions. For example, BitMEX, a well-known derivatives exchange, was identified as a "money laundering platform" for failing to implement KYC/AML, and its founder admitted to violating BSA and paid a $100 million fine.[16][17] Another case is the criminal case of a former Coinbase employee who was charged with "profiting by bypassing KYC supervision" for suspected insider trading, which highlights the regulatory authorities' efforts to crack down on money laundering and fraud in the crypto industry.

Since the EU adopted Anti-Money Laundering Directive 5 (5AMLD) in 2018, it has included virtual currency exchanges and custodian wallet service providers in the scope of anti-money laundering supervision, requiring them to register licenses and fulfill KYC/AML obligations[18]. Member states have revised their domestic regulations accordingly (such as the German Anti-Money Laundering Act and the French Monetary and Financial Code) to implement identity verification and suspicious reporting for crypto service providers. In 2023, the EU formally adopted the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA, Regulation No. (EU) 2023/1114), establishing a unified licensing system for crypto asset service providers (CASPs)[19]. MiCA itself mainly focuses on market regulation and investor protection, but in parallel, the EU reached an agreement in 2024 on the Anti-Money Laundering Regulation (AMLR) and the Anti-Money Laundering Directive 6 (6AMLD), which impose higher due diligence and beneficial owner identification requirements on obligated entities, including CASPs[20]. In addition, the EU plans to establish a dedicated Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA) to strengthen cross-border supervision and coordination. This means that every cryptocurrency exchange operating within the EU must establish rigorous KYC procedures, continuously monitor customer transactions, and cooperate with law enforcement agencies to combat money laundering activities, or face penalties such as license revocation and hefty fines.

Asian financial centers have also followed international standards and established AML (Anti-Money Laundering) frameworks for crypto assets. Regulators in Asian jurisdictions such as Hong Kong, Singapore, and Japan have emphasized that centralized exchanges and other types of VASPs must establish comprehensive AML compliance mechanisms to prevent them from becoming channels for money laundering and illicit fund flows.

In 2022, Hong Kong amended the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance (AMLO) and implemented a mandatory licensing system for Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs) from June 2023.[21] According to the Ordinance and the guidance of the Securities and Futures Commission, trading platforms must strictly implement measures such as customer identification, risk assessment, transaction monitoring and regular audits, and comply with travel rules requirements to promptly report customer and transaction information to counterparty institutions.[21]

Singapore has brought digital payment token service providers under its control through the Payment Services Act (PSA) in 2019, and the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has issued a Notice (PSN02) detailing the AML/CFT requirements, including applying travel rules to virtual asset transfers with an equivalent value of more than S$1,500 and implementing enhanced due diligence for non-custodial wallet transactions.[22]

Japan amended the Payment Services Act and the Proceeds of Organized Crime Act in 2017, requiring cryptocurrency exchange operators to register with the Financial Services Agency and fulfill KYC and anti-money laundering obligations.[23] Japan stipulates that exchanges must verify information such as name and address when opening accounts for customers, monitor transactions, and conduct additional reviews for transactions exceeding a certain amount (such as the equivalent of 100,000 yen).[23] It is worth mentioning that Japan is also one of the active promoters of travel rules, and has incorporated this requirement into domestic law, requiring the transmission of sender and recipient information for virtual asset transfers exceeding 100,000 yen.[24]

The above comparison shows that KYC/AML regulation has become the "bottom line" consensus in the global crypto asset trading field: although the legislative techniques and implementation efforts of different jurisdictions are slightly different, they all recognize that strengthening customer identity verification and transaction transparency is the primary link to protect the financial system from criminal abuse [1]. The formation of this consensus has brought a unified compliance threshold to cross-border crypto businesses to some extent - global institutions must meet the KYC standards of each jurisdiction and cooperate with suspicious funds monitoring, otherwise it will be difficult to obtain an operating license. However, at the same time, there are still differences in the enforcement efforts and specific rules of different jurisdictions (for example, the United States focuses on criminal prosecution of violators, the European Union focuses on unified regulation, and the Asian region focuses on license management, etc.), which requires companies to take into account the regulatory details of each region when formulating global compliance strategies.

2.2 Independent custody and segregation system for client assets

Segregation of client assets is a core mechanism in financial regulation for protecting investor interests and preventing the transmission of institutional bankruptcy risks. In the traditional securities and futures sectors, various countries have long had mature rules (such as the US SEC's Client Funds Protection Rules and the UK FCA's Client Assets Rules) to ensure that brokers keep client funds separate from their own funds. For cryptocurrency trading platforms, a series of recent events (including the collapse of a global exchange in late 2022 due to the misappropriation of client funds) have increasingly highlighted the importance of segregation of client assets. Regulators across jurisdictions generally recognize that platforms must not commingle user-held digital assets with their own assets, and are strictly prohibited from using client assets for lending or investment without authorization; otherwise, a financial crisis on the platform would severely damage investor rights. This has become one of the regulatory red lines in major jurisdictions.

The EU has set forth clear requirements for the custody and segregation of clients' crypto assets in the Crypto Asset Market Regulation (MiCA). MiCA stipulates that authorized crypto asset service providers (CASPs) must legally and operationally segregate client assets from their own assets when holding crypto assets on behalf of clients[3]. Specifically, CASPs should clearly identify client assets on a distributed ledger and ensure that the ledger records distinguish the tokens held by clients from the company's own tokens[3]. MiCA further emphasizes that client assets are legally independent of the CASP's property, and even if the platform goes bankrupt and is liquidated, its creditors have no right to claim against the crypto assets held by clients[25]. In other words, clients have ownership or beneficial rights to the assets held in custody, which do not become general claims due to the platform's bankruptcy. This provision is consistent with the existing investor asset segregation principle in the EU securities sector. Articles 67 and 68 of the official MiCA text (Regulation (EU) 2023/1114) published in June 2023 detail the custodian obligations and asset segregation measures of CASPs, including the separate management of customer assets and proprietary assets at the technical and operational levels, and the establishment of corresponding internal control and audit mechanisms to ensure effective segregation [26][27]. The EU's move aims to learn from past crypto platform bankruptcies, eliminate legal uncertainty regarding the ownership of customer assets, and provide investors with bankruptcy remoteness protection similar to that in traditional finance.

At the federal level in the United States, there are currently no uniform legal provisions specifically for cryptocurrency custody, but some states and regulatory agencies have begun to take action. Among them, the New York State Department of Financial Services (NYDFS), known for its stringent regulations, issued guidance in January 2023 for institutions holding cryptocurrency custody licenses (i.e., companies holding New York BitLicenses or trust licenses). The NYDFS explicitly requires that cryptocurrency custodians "separately account for and segregate clients' virtual currencies from their own holdings." This can be achieved by creating separate wallets for each client, using internal ledgers, or placing all client assets in a master account strictly separated from their own assets. Regardless of the method used, custodians must ensure that client assets are not included on their own balance sheets and are not used for any purpose other than secure custody. The NYDFS also reiterated that custodians must not misappropriate, lend, or divert client assets without the client's explicit instructions. This guidance is seen as a regulatory response from the NYDFS to recent industry scandals, such as the Celsius and FTX cases, in which courts disputed whether clients' crypto assets held in custody belonged to the clients' property or bankruptcy estates, resulting in losses for the clients. The NYDFS regulation establishes the priority of client assets over other claims. While the NYDFS guidance only applies to entities with business ties to New York, it is widely regarded as a benchmark for client asset segregation in US practice, given New York's exemplary role in crypto regulation. Other states, such as Wyoming, have similar provisions in their Digital Assets Acts, recognizing the legal status of custodied digital assets as client-held assets, thus providing bankruptcy remoteness protection.

In its 2023 Guidelines for Virtual Asset Trading Platform Operators, the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) listed "proper asset custody" as one of the core principles that licensed platforms must follow[5]. According to the guidelines, platforms should take measures to ensure the safe custody of customers' virtual assets, including using high-security cold wallets to store the vast majority of customer assets, and setting strict withdrawal limits and multi-signature permissions for hot wallets. In addition, the guidelines require "separate holding of customer assets", that is, platforms must clearly distinguish between customers' virtual assets and their own assets. In practice, Hong Kong licensed platforms usually deposit customers' fiat currency funds in independent trust accounts, and store customers' cryptocurrency assets in dedicated wallet addresses or custodian accounts to achieve legal and operational isolation. For example, some platforms declare that 98% of customer assets are stored in cold wallets and managed by independent custodians, and only 2% are used to meet daily withdrawal needs, and regularly report the asset reserve status to the regulator. These measures are intended to prevent platforms from misappropriating customer assets for self-operation or other purposes, and to reduce the risk of customer loss in extreme situations such as platform bankruptcy or hacker attacks. In late 2023, the SFC further issued a notice emphasizing the need for strong governance and auditing in client asset custody. It required senior management to regularly review custody arrangements and private key management processes, and introduced external audits to verify client asset holdings, thereby enhancing transparency. These requirements highlight the Hong Kong regulators' emphasis on client asset security, striving to avoid repeating the mistakes of overseas platforms and maintain Hong Kong's reputation as a compliant crypto market through rigorous systems.

In approving licenses for digital payment token service providers, Singapore's MAS also examines whether applicants possess reliable custody solutions and internal controls to ensure that customer assets are not misused. While Singapore has not yet enacted specific regulations on customer asset segregation, the MAS has issued guidelines advising licensed institutions to store customer tokens in independent on-chain addresses, separating them from operating funds, and to establish daily reconciliation and asset verification mechanisms. In Japan, the Financial Services Agency (FSA) urged cryptocurrency exchanges to implement "trust-based" customer assets as early as 2018, entrusting customers' fiat currency deposits to a third-party trust institution for safekeeping, while requiring at least 95% of customers' cryptocurrency assets to be stored offline. The 2019 amendment to the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act further included cryptocurrency assets within the scope of financial products and formally stipulated that exchanges must verify customer assets daily to ensure that the amount of customer assets is not lower than the required level; if it is lower, it must be immediately reported to the regulator. This effectively establishes a customer asset reserve system, which is also a special form of segregation requirement.

In summary, the segregation of customer assets has become a common bottom line for regulation in various jurisdictions. Whether in Europe and the United States or in the Asia-Pacific region, regulatory agencies have required cryptocurrency trading platforms to independently custody and manage customer assets in the form of explicit regulations or administrative guidelines, and not to treat them as company property or misappropriate them for other purposes[25]. The implementation of this requirement helps protect investors from the risk of misappropriation by platform insiders or the division of assets by creditors, and enhances market confidence. However, when operating across jurisdictions, institutions still need to pay attention to the specific compliance details in different regions. For example, some regions require the introduction of a third-party independent custodian, while others allow platforms to keep their own assets but must meet capital or insurance requirements. These differences will be discussed in the relevant chapters later. In any case, "not misappropriating customer assets" is the red line among red lines, and any deviation may result in severe regulatory penalties or even criminal liability.

03. Consensus on Regulatory Red Lines: Combating Market Manipulation and Preventing Conflicts of Interest

This chapter explores two bottom lines related to market fairness: anti-market manipulation and conflict of interest prevention.

3.1 Anti-market manipulation: Market integrity and manipulation prevention

The price volatility and relative lack of traditional market infrastructure in the crypto asset market make it susceptible to manipulation, including wash trading, pump and dump, insider trading, and market manipulation. If market manipulation is allowed to run rampant, it will not only infringe on the rights and interests of investors, but may also undermine the market pricing function and weaken public trust in the crypto market. Therefore, regulatory agencies in major jurisdictions generally regard combating market manipulation and insider trading as a regulatory red line, requiring trading platforms and related intermediaries to take measures to monitor and prevent suspicious trading activities, and report to regulatory authorities when necessary to ensure a fair and orderly market [4]. Legally, many countries classify serious market manipulation as a criminal offense and apply the penalties of traditional financial markets.

In the United States, anti-manipulation laws targeting the securities and derivatives markets are relatively comprehensive. For digital tokens classified as securities, Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and SEC Rule 10b-5 prohibit any market manipulation or securities fraud; insider trading is also prohibited and punished under federal securities laws and case law. For digital assets considered commodities (such as Bitcoin and Ethereum as defined by US regulators), the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) empowers the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to govern manipulation in the derivatives market and to take enforcement action against fraudulent manipulation involving the spot market. In recent years, US law enforcement agencies have actively utilized these laws to combat illegal activities in the crypto market: for example, in 2021, the US Department of Justice prosecuted an insider trading case involving cryptocurrencies, accusing an exchange employee of profiting by buying tokens before they were listed; the SEC filed a parallel securities fraud charge, arguing that the relevant tokens were securities. This was the first case of "insider trading" enforcement in the crypto field, demonstrating that the US will not relax its punishment for unfair trading based on the form of the asset. Also noteworthy is the CFTC's 2021 lawsuit against an executive of a crypto trading platform, accusing them of tacitly allowing users to wash trading, thereby creating false liquidity and misleading the market, and pursuing liability under the anti-manipulation provisions of the Commodity Exchange Act. While the US lacks specific legislation targeting manipulation in the crypto spot market, regulators have already conducted numerous enforcement actions using existing laws (securities laws, commodity laws, and anti-fraud provisions). Meanwhile, state attorneys general offices in New York and other states have utilized broad anti-securities fraud authorizations such as the Martin Act to investigate trading platforms suspected of manipulation (e.g., the 2018 NYAG investigation report on fabricated trading volumes at multiple exchanges). Overall, the US emphasizes the principle of "legal neutrality," meaning that even emerging crypto assets, if manipulated in a manner similar to traditional securities/commodities, may face corresponding legal sanctions.

The EU has established a comprehensive ban on insider trading and market manipulation in the traditional securities sector through the Market Abuse Regulation (MAR). However, the MAR mainly applies to financial instruments in regulated markets and does not directly cover most crypto assets. To fill this gap, the EU has introduced market integrity obligations for crypto assets in the MiCA. Article 80 of the MiCA requires that no one who is professionally engaged in crypto trading shall use inside information to trade related assets or engage in manipulation. At the same time, the MiCA requires CASPs operating trading platforms to establish market monitoring mechanisms and have the ability to identify and deal with market abuse [4]. Specific measures include: the trading system must have built-in monitoring algorithms that can detect possible signs of manipulation such as abnormally large orders and frequent order cancellations; maintain the platform's trading order when prices fluctuate sharply to prevent manipulation of market conditions; set thresholds for price increases or decreases or trading volume to automatically reject orders that exceed reasonable limits; and report to the competent authorities in a timely manner when suspicious manipulation or insider trading is discovered. In addition, the MiCA requires the platform to continuously disclose buy and sell quotes and depth information, as well as timely disclose transaction data, in order to improve market transparency and reduce the space for opaque operations. These regulations essentially draw on the EU's experience in the securities market, applying many of the "same business, same risk, same rules" principles to crypto asset trading. In 2025, the EU, in drafting a new Anti-Money Laundering Regulation (AMLR), mentioned plans to ban anonymous transactions and privacy coins (see below), which is also part of preventing market manipulation (improving traceability). In terms of enforcement, with the MiCA coming into effect, securities regulators in member states (such as the French AMF and German BaFin) will have clear authorization to investigate and prosecute manipulation in the crypto market. For example, if someone incites a group in a Telegram group to collectively buy a token to drive up its price and then sell it for profit, they may be found guilty of violating the market manipulation ban and punished. Thus, it is clear that the EU is gradually extending its regulation of market abuse to the crypto space, achieving extended and consistent regulation.

When issuing licenses to virtual asset trading platforms, the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) requires licensed platforms to establish market monitoring departments or systems to monitor abnormal transactions in real time. According to SFC guidelines, platforms should promptly identify and prevent transactions attempting to manipulate the market, such as wash trading through related accounts or false order cancellations, and retain logs for regulatory inquiries. If significant suspicious manipulation is discovered, the platform must report to the SFC and law enforcement agencies. Although Hong Kong currently does not include crypto assets under the market manipulation offenses under the Securities and Futures Ordinance (because most crypto assets are not defined as securities), licensed platforms still have a compliance obligation to ensure market fairness. This is a practice of "implementing regulatory objectives through licensing conditions." In Singapore, the MAS applies the market manipulation and insider trading provisions of the Securities and Futures Act (SFA) to digital tokens listed in regulated markets (such as authorized exchanges) if they are determined to be securities or derivatives. However, for pure crypto asset trading not included in the definition of financial instruments, Singapore currently mainly requires traders to conduct self-regulatory monitoring through industry guidelines. Nevertheless, the MAS has repeatedly issued warnings emphasizing the risks of money laundering and manipulation in the crypto market, reminding investors to be vigilant. This year (2025), Singapore is also considering amending relevant laws to include certain token trading activities involving public interest under the Financial Markets Conduct Act, such as prohibiting the dissemination of false or misleading information that affects token prices, in order to address the problem of insufficient enforcement basis.

It's worth noting that to assist regulators and platforms in fulfilling their monitoring obligations, some specialized blockchain analytics companies and market regulatory technology solutions are beginning to be applied to anti-manipulation efforts. For example, some trading platforms use on-chain analytics tools to monitor the flow of funds between multiple accounts to determine if there is "multi-account collusion for manipulation"; other institutions have developed AI models that can identify abnormal price patterns and order book behavior. Regulatory agencies are also increasingly relying on such technologies to improve monitoring efficiency. For instance, the U.S. SEC has established a dedicated crypto asset monitoring team that uses big data analysis of exchange trading records to detect abnormal fluctuations and investigate whether there is behind them being manipulated. The EU's ESMA and regulators in various countries are also exploring the establishment of a cross-platform crypto trading reporting database to identify cross-market manipulation.

In summary, combating market manipulation and insider trading is a common regulatory red line across jurisdictions, with differences only in specific enforcement methods due to variations in regulatory scope and legal authorization. Looking at the trend, as the crypto market deepens its integration with traditional finance, countries will increasingly tend to incorporate crypto trading activities into existing market regulatory frameworks, achieving equal constraints. For example, the Financial Stability Board's (FSB) 2023 recommendations emphasized that countries should ensure "effective regulation and supervision of the crypto asset market to maintain market integrity," including equipping sufficient enforcement tools to curb manipulation and fraud. This global guiding principle is expected to translate into clearer regulatory requirements in various jurisdictions, ensuring that manipulating the crypto market will be legally prosecuted, whether in New York, London, or Singapore. For market participants, this means creating a fairer and more transparent trading environment, a necessary condition for the long-term healthy development of the industry.

3.2 Conflict of Interest Prevention: Business Separation and Internal Governance

Conflict of interest prevention is a fundamental requirement for ensuring financial institutions fulfill their fiduciary responsibilities and protect customer interests. In the cryptocurrency trading sector, potential conflicts of interest include: trading platforms acting as both market operators and proprietary traders, or controlling affiliated market makers, potentially profiting from customer order information; platforms issuing their own tokens and listing them for trading, leading to price maintenance and information asymmetry issues; and executives or employees possessing sensitive market information and engaging in personal trading (insider trading). Without regulation, these conflicts of interest will harm customer interests and market fairness, and may even trigger systemic risks (as seen in the collapse of some exchanges due to affiliated companies engaging in high-risk trading and misappropriating customer assets). Therefore, regulatory agencies in various countries consider preventing and managing conflicts of interest a red line, requiring cryptocurrency service providers to establish internal controls and systems to identify, mitigate, and disclose potential conflicts.

MiCA sets forth clear and mandatory provisions for the management of conflicts of interest by CASPs. According to Article 72 of MiCA[28], crypto asset service providers must develop and maintain effective policies and procedures to identify, prevent, manage and disclose potential conflicts of interest. These conflicts may occur between: (a) the service provider and its shareholders, directors or employees; (b) different clients; or (c) when the service provider and its affiliates are conducting multiple business functions. MiCA requires service providers to assess and update their conflict of interest policies at least annually and to take all appropriate measures to resolve any conflicts. At the same time, service providers must disclose the nature, source and mitigation steps of general conflicts of interest in a prominent position on their official website so that clients are informed. For CASPs operating trading platforms, MiCA further stipulates that there should be particularly comprehensive procedures to avoid conflicts of interest between themselves and their clients in trading, including preventing transactions with proprietary counterparties in the matching system and restricting platform personnel from trading with undisclosed information. MiCA also authorizes regulatory technical standards to refine disclosure formats, which shows that the EU regards conflicts of interest as a key area requiring strong regulatory intervention. One of the considerations behind MiCA is to learn from the risks arising from proprietary trading and related-party transactions by some exchanges in the past, ensuring "fair competition": platforms cannot operate as casinos while simultaneously placing bets themselves, thus deceiving other gamblers. It is worth mentioning that MiCA not only requires service providers to manage conflicts of interest themselves, but also has similar provisions for asset reference stablecoin issuers, such as requiring disclosure of potential conflicts of interest arising from the management of reserve assets, reflecting the EU regulatory requirement to establish a firewall against conflicts of interest for all types of entities.

Traditional US financial markets have long had mechanisms in place to address conflicts of interest (such as the separation of trading and proprietary trading between exchanges and brokers, and firewall regulations for banks). While there are currently no specific regulations mandating business separation or prohibiting proprietary trading for the crypto space, regulatory officials have repeatedly expressed concerns about the risks of "vertical integration." For example, a commissioner of the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) stated in a 2024 public statement that the integration of multiple roles—exchange, broker, market maker, and custodian—into one entity, like FTX, coupled with a lack of external oversight, created significant conflicts of interest and risks. The statement argued that regulators should develop rules to restrict such vertically integrated structures. The statement noted that FTX's collapse "highlighted the serious harm caused by the lack of regulatory oversight of conflicts of interest." Although FTX was not fully regulated in the US at the time, its collapse prompted US legislators and regulators to reflect on whether it was necessary to enact regulations similar to the "separation of trading and advisory services" in the Securities Act for crypto exchage. Currently, some proposals in the US Congress (such as the draft Digital Goods Consumer Protection Act of 2022) have considered prohibiting crypto trading platforms from engaging in certain activities that conflict with customer interests, such as prohibiting exchanges from lending customer assets or restricting their affiliates from participating in platform trading, but these bills have not yet been passed. On the other hand, US regulators have been advocating for conflict of interest prevention through enforcement. For example, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), in its warnings to platforms such as Coinbase, mentioned that their actions, such as allowing executives to sell tokens in advance and the platform itself investing in and listing token projects, may constitute a conflict of interest and harm investors, and should be subject to full disclosure and control. Another example is the US Department of Justice's prosecution of certain practitioners for allegedly profiting from trading using undisclosed token listing information, which also falls under the punishment of insider conflict. Furthermore, at the licensing level, the New York State Department of Financial Services requires BitLicense-holding companies to submit conflict of interest policies, specifying restrictions on personal transactions by directors and executives, as well as mitigation measures for potential conflicts of interest arising from multiple business operations. These measures indicate that although the US does not have a comprehensive set of regulations like MiCA, enforcement and regulatory actions are gradually incorporating conflict of interest into the compliance priorities of crypto platforms.

Hong Kong's Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) explicitly requires licensed platforms to avoid conflicts of interest in its "Guidelines for Virtual Asset Trading Platforms." Specific measures include: platforms are prohibited from engaging in any form of proprietary trading for their own accounts (i.e., not acting as "market makers"); if a platform's group has subsidiaries engaged in market-making activities, they must report to the SFC and ensure a strict information firewall (Chinese Wall) to prevent insider information leaks; personal crypto trading by platform executives and employees is also restricted, requiring declaration and internal compliance approval. Furthermore, if a platform intends to list tokens with which it has a vested interest (such as tokens of projects invested in by the platform or native tokens issued by the platform), the SFC requires full disclosure and may, depending on the circumstances, refuse approval for listing, to prevent platforms from "listing on one hand and profiting from the other." This practice in Hong Kong is consistent with its securities market regulatory practices, such as the separation of revenue between brokerage and proprietary trading, and avoiding conflicts between agency trading and proprietary trading. After the SFC issued licenses in 2023, the first batch of licensed platforms in Hong Kong declared in their public information that they do not engage in proprietary trading and do not compete with clients for profits, in order to gain investors' trust. This establishes a red line in the system: the platform acts only as an intermediary and matchmaker, not as a market counterpart, thereby reducing conflicts of interest through the mechanism.

International organizations are also concerned about this issue. In its senior recommendations on crypto regulation released in July 2023, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) clearly stated that each jurisdiction should "ensure that crypto asset service providers that combine multiple functions are subject to appropriate regulatory oversight, including requirements for conflicts of interest and separation of certain functions"[26]. This is equivalent to calling on countries at the global level to regulate the business models of crypto trading platforms and, if necessary, to force the separation of certain conflicting functions (such as the separation of trading and custody, and the separation of brokerage and market making) to prevent one institution from being both player and referee. The FSB's position is supported by organizations such as IOSCO: In its 2022 consultation report, IOSCO also recommended that regulators should require crypto exchage to disclose proprietary trading, restrict improper trading by employees, and may draw on the experience of structural segmented regulation in traditional finance to reduce conflicts of interest. It is foreseeable that, driven by the FSB and IOSCO, "the same risk, the same function, the same rules" will be gradually implemented in the field of conflict of interest management, and a unified international standard may emerge in the near future.

In summary, conflict of interest prevention has been incorporated into the basic requirements of cryptocurrency industry regulation in various countries. From the mandatory rules of the EU's MiCA to the licensing conditions in Hong Kong and Singapore, and the statements and enforcement by US regulators, all send a clear signal: trading platforms and other intermediaries must establish sound internal control mechanisms to prevent the use of unfavorable customer information for improper gain, and any such behavior must be promptly disclosed and stopped. The establishment of this red line will help restore market confidence damaged by several scandals and promote the industry towards greater transparency and integrity. For operating institutions, this requires investing more resources in internal governance, such as introducing independent compliance officers to oversee trading, conducting regular conflict of interest risk assessments, and training employees on ethical standards, in order to meet the expectations of regulators in various regions and maintain their own reputation.

04. Differences in Regulatory Approaches to Stablecoins

Stablecoins, as crypto tokens pegged to fiat currencies or other assets, have rapidly developed globally, attracting significant attention from regulatory bodies worldwide. On the one hand, stablecoins promise to improve payment efficiency and financial inclusion; on the other hand, their widespread use could impact financial stability and monetary sovereignty, particularly when stablecoin issuance lacks sufficient reserves or transparency, posing a greater risk of collapse (such as the 2022 collapse of the algorithmic stablecoin UST). Therefore, countries are exploring regulatory pathways for stablecoins. However, due to differences in legislative philosophies and financial systems, stablecoin regulation has become one of the most contentious issues across legal jurisdictions. The main disagreements lie in: the licensing authority for issuance, reserve and capital requirements, investor protection measures, and restrictions on transaction usage.

4.1 Licensing and Limits of Fiat-backed Stablecoins

The EU classifies stablecoins into two categories within MiCA: Electronic Money Tokens (EMTs), which are stablecoins pegged to a single fiat currency; and Asset Reference Tokens (ARTs), which are stablecoins pegged to a basket of assets or fiat currency. MiCA imposes strict entry and regulation on both categories. For EMTs, issuers must obtain a license from a credit institution (bank) or electronic money institution and issue tokens with the approval of the regulatory body. Issuers must hold highly liquid reserve assets (mainly corresponding fiat currency deposits or high-quality government bonds) equivalent to the issued tokens to ensure 1:1 solvency. MiCA also prohibits paying interest to EMT holders to prevent them from competing with deposits. Most notably, to prevent stablecoins from outside the Eurozone from impacting monetary policy, MiCA introduces a trading cap: for non-Euro-pegged stablecoins (such as USDT pegged to the US dollar), daily trading volume cannot exceed €200 million or 1 million transactions; otherwise, issuers must take measures to restrict usage (suspending issuance or redemption if necessary). The dual thresholds of "€200 million/day" and "1 million transactions/day" aim to prevent any single stablecoin from becoming excessively popular and replacing the euro for payments. This is a unique preventative regulatory measure in the EU, attracting significant attention from the industry (known as the "hard cap" for stablecoin trading). Furthermore, MiCA imposes higher requirements on issuers of Significant EMT/ART stablecoins, including more frequent reporting, stricter liquidity management, and reserve custody rules. From 2024, MiCA's regulations on stablecoins will take effect first, and issuers must achieve full compliance after the transition period; otherwise, they will be prohibited from providing stablecoin-related services within the EU. This EU framework is arguably the most comprehensive and stringent stablecoin regulation globally, benchmarking the regulatory standards for payment instruments issued by electronic money institutions and banks in traditional finance.

Compared to the European Union, the United States currently lacks specific federal regulations for stablecoins, creating a significant regulatory vacuum. In recent years, the US Congress has issued numerous reports and draft bills regarding stablecoins. A 2021 report by the President's Working Group on Financial Markets (PWG) recommended that stablecoin issuance be restricted to regulated depository institutions (such as banks) and called for congressional legislation. Subsequently, several proposals, including the Stablecoin Transparency and Protection Act and the Digital Commodity Stablecoin Act, were drafted, but none passed due to differing political views. As a result, under current law, stablecoin issuers can only operate within the existing framework: some companies regulated by trust bylaws (such as Paxos and Circle, which operate under state trust licenses) issue stablecoins and are subject to regulation by state financial regulatory authorities; USDT issued by other unlicensed foreign companies (such as Tether) operates outside of US regulation, only partially subject to constraints due to its bank custody accounts being subject to US regulations. Federal regulatory agencies can only exert indirect pressure; for example, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) allowed national banks to issue stablecoins in 2021, but with prudential conditions, and the Federal Reserve and the FDIC warned banks to be cautious about participating in stablecoin reserve operations. At the state level, the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) was the first to implement reserve and audit requirements for stablecoins under its regulation (such as NYDFS-approved BUSD and USDP). In 2022, the NYDFS issued guidelines requiring that USD stablecoins issued in New York must be 100% held in cash or short-term US Treasury bonds, with daily redemptions and no interest. Wyoming, on the other hand, has passed innovative laws allowing Reserve Banks for Digital Assets (SPDIs) and newly established stablecoin institutions to issue stablecoins, but there are no successful cases yet.

In the absence of unified regulations, the US stablecoin market is highly fragmented: large players like Tether and Circle maintain high reserves and regularly disclose asset proofs, but loopholes still exist (e.g., TerraUSD, an algorithmic coin, grew rapidly in a regulatory vacuum and ultimately collapsed). This regulatory vacuum alerted US legislators, and in the latter half of 2023, Congress again attempted to push for the "Stablecoin Regulatory Act," aiming to establish a federal licensing system and grant the Federal Reserve oversight of non-bank stablecoin issuance. However, the legislative process remains uncertain. Against this backdrop, US authorities are temporarily managing risks through enforcement: for example, the SEC has issued warnings about certain stablecoins suspected of being securities (such as a dollar-denominated stablecoin issued by a social media platform), while the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has classified mainstream stablecoins as commodity assets and reserved enforcement power. Overall, US stablecoin regulation is currently in a state of "lagging regulations, state-level self-governance, and scattered federal guidance," significantly different from the EU's comprehensive legislative model.

Japan has adopted a relatively conservative approach to the regulation of stablecoins. In June 2022, the Japanese Diet passed amendments to laws such as the Payment Services Act, which for the first time clarified the legal status and issuance qualifications of stablecoins. The new law classifies stablecoins as "electronic payment instruments" and requires that they can only be issued by regulated legal institutions, including registered banks in Japan, restricted remittance operators (which must have high capital) or trust companies[6]. This provision excludes general private enterprises, meaning that entities like Tether cannot legally issue stablecoins in Japan. The new law also stipulates that eligible stablecoins must be pegged to the Japanese yen or other fiat currencies and can be redeemed by the holder at face value. At the same time, it prohibits the issuance of non-collateralized forms such as algorithmic stablecoins. For reserves, 100% fiat currency margin deposits are required to be held by regulated institutions.

Furthermore, Japan's Financial Services Agency (FSA) is very cautious about foreign stablecoins entering the Japanese market. Currently, most Japanese exchanges do not list major overseas stablecoins (such as USDT), while JPY-pegged coins issued by trust companies (such as "Progmat Coin" issued by the Mitsubishi UFJ Trust) are currently being tested. In 2024, Japan discussed further restrictions: for example, the FSA proposed prohibiting ordinary banks from directly issuing stablecoins on public blockchains (considering the risk too high, only trust banks and similar entities are permitted to issue them), and requiring full application of KYC/travel rules for stablecoin transfers. Under the Japanese model, stablecoins are more like an alternative to bank deposits, strictly regulated by banking laws and payment regulations, reflecting a high degree of emphasis on financial stability and consumer protection. The advantage of this model is high security, but the disadvantage is that it inhibits non-bank innovation. Currently, there is no large-scale circulation of stablecoins in Japan, but if major banks plan to issue yen-denominated stablecoins, they will operate entirely within the regulatory purview, and the risks will be relatively controllable.

In 2022, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) issued a discussion paper, explicitly stating that algorithmic stablecoins would not be allowed and that it planned to focus on regulating payment-type stablecoins that are referenced to fiat currency. The Stablecoin Ordinance (draft name) was completed in 2023 and came into effect in August 2025[7]. The ordinance requires that issuers of any stablecoins pegged to fiat currency issued or circulated in Hong Kong must obtain a license from the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA). The license application must meet strict conditions, including establishing an entity in Hong Kong, having a certain amount of statutory capital, implementing risk management and technical audits, etc. The ordinance requires issuers to hold 100% reserve assets (limited to highly liquid assets) and redeem stablecoins at face value when holders raise them. At the same time, the HKMA is given supervisory and inspection powers to review reserve status and operations. The special feature of Hong Kong regulation is that it does not limit banks to issuing stablecoins, but ensures that any issuer is subject to prudential supervision similar to that of banks. This may leave some room for non-bank financial technology companies to issue stablecoins, but the regulatory costs are also not low. Hong Kong plans to complete its first batch of license approvals in 2024-25, emphasizing a small-scale, steady approach. Notably, Hong Kong's regulations include stablecoins within the scope of anti-money laundering ordinances, requiring issuers and distributors to implement KYC/AML obligations. This move by Hong Kong establishes a new regulatory benchmark for stablecoins in another Asian financial center, unlike Singapore, which primarily relies on guidelines rather than legislation. For the market, Hong Kong's framework provides a compliant path for issuing and operating stablecoins, potentially attracting licensed stablecoin issuers to apply.

4.2 Capital and Reserve Requirements for Non-Statutory Asset-Backed Stablecoins (Asset-Pegged Tokens)

Besides stablecoins pegged to a single fiat currency, some stablecoins are backed by a basket of fiat currencies, commodities, or crypto assets (such as the early-envisioned Libra, which was pegged to multiple reserve assets), or maintain their peg through algorithmic collateralization. These stablecoins, known as "Asset Reference Tokens" (ARTs), have more complex value stabilization mechanisms and carry higher risks. Regulators in various countries tend to be more cautious about ARTs. Especially after the Libra project (later renamed Diem) triggered a global regulatory backlash in 2019, most jurisdictions explicitly stated that such cross-border basket tokens could threaten financial sovereignty and stability and should be strictly regulated.

The EU's MiCA (Military Reference Token) has brought Asset Reference Tokens (ARTs) under its regulatory purview, requiring issuers to obtain licenses and comply with a series of requirements similar to those for EMTs, including white paper disclosure, reserve custody, capital adequacy, and liquidity plans. However, given that ARTs are not pegged to a single fiat currency, MiCA's regulations are more stringent: First, ART issuers must hold a relatively higher minimum capital (at least €350,000 or 2% of the value of reserves), exceeding the requirements for EMT issuers. Simultaneously, ART issuers must establish clear reserve asset custody policies, ensuring that reserve assets are completely segregated from the issuer's own assets and cannot be misappropriated. MiCA stipulates that reserve assets can be held by qualified custodians (such as licensed CASP custodians or banks) and requires highly diversified reserves to reduce correlation risk. Furthermore, ART issuers must establish a regular audit mechanism, disclosing reserve composition and audit reports quarterly to enhance transparency. For significant ARTs, MiCA authorizes regulators to impose additional requirements, such as limiting business size or requiring more detailed risk analysis. The EU's MiCA also prohibits issuers from providing any additional profit incentives to ART holders, aiming to prevent ART from becoming a disguised investment product. Overall, the MiCA's requirements for ART cover governance, risk management, and user protection, hoping to bring its risks to a manageable level.

Following the Libra incident, multiple US departments exerted pressure on Libra, forcing the project to modify its design or even terminate it. While no specific law has been enacted, it can be inferred that if a Libra-like ART were to emerge, the US might invoke Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act (Systemically Important Payment Instruments) or securities laws to regulate it. For example, if ART involves a basket of securities as a reserve, the SEC might classify it as an ETF fund unit, requiring registration; if it involves payment functions and is large-scale, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) might designate the issuer as a systemically important institution subject to Federal Reserve regulation. Currently, there are no large-scale ART operations in the US market (most mainstream stablecoins are single-currency pegged), so regulatory disagreements mainly stem from differing stances. Federal Reserve officials have stated that multi-currency stablecoins may require special review by the central bank. Some US think tanks have suggested treating such stablecoins as "shadow banking currencies," requiring their issuers to adhere to strict asset portfolio restrictions and reserve requirements, similar to money market funds. However, due to a lack of practical examples, the US has not established a fixed path for this approach. In terms of enforcement, if ART leads to investment losses, regulators may invoke commodity or securities laws. For example, the algorithmic stablecoin Ampleforth was investigated by the SEC for potentially selling securities through an ICO; its algorithmic nature (pegged to a basket of assets or an algorithmic formula) did not exempt it from securities laws. These examples demonstrate the "principle-driven" nature of US regulation: there is no specific law, but relevant laws are applied on a case-by-case basis.

In 2022, Singapore consulted the public on stablecoins, proposing rules for single-currency stablecoins (such as requiring the primary reference currency to be a G10 currency and minimum reserve asset quality requirements), but tended to discourage multi-asset-backed stablecoins for the time being. The MAS's approach is to first regulate single-currency stablecoins and then decide whether to allow more complex structures based on international consensus. Hong Kong's current regulations mainly target fiat-pegged coins, directly refusing to permit non-fiat-pegged tokens (such as algorithmic stablecoins and commodity-backed coins). In 2023, the South Korean Financial Services Commission declared that exchange trading of algorithmic stablecoins was not allowed and held a negative attitude towards any stablecoins with yields or complex mechanisms. Japan, which only allows fiat-pegged stablecoins, has no room for ART (Artificial Stablecoin) regulations. In summary, there are significant differences in stablecoin regulation between Europe and the US: the EU has established a detailed set of regulations through MiCA, especially specifying requirements for international basket currencies; the US is still discussing and exploring, focusing more on legislation for single-currency stablecoins in the short term. Most major Asian economies are cautious and have adopted a tight approach. This difference means that companies engaged in stablecoin businesses must address vastly different compliance requirements when expanding globally. Operating in the EU market requires obtaining a license and monitoring daily transaction volumes to ensure they do not exceed thresholds; in the US market, while there are no explicit licensing requirements, they face uncertain regulatory risks and potential enforcement; and in regions like Japan and Hong Kong, they may face direct licensing restrictions or bans. Therefore, regulatory disagreements are particularly pronounced in this area and represent a key challenge for future international regulatory coordination.

05 Regulatory Differences: Market Access and Innovation Boundaries

This chapter discusses three other issues where significant cross-jurisdictional regulatory differences exist: regulation of crypto derivatives trading, the legality of privacy coins, and regulatory exploration of Real Asset Tokenization (RWA) and decentralized finance (DeFi). Because these areas involve investor protection, criminal enforcement, technological anonymity, and the boundaries of financial innovation, different countries have adopted different strategies, and a unified international standard has not yet been established.

5.1 Market Access and Investor Protection for Crypto Derivatives

Crypto derivatives refer to futures, options, and contracts for difference (CFDs) based on the price of crypto assets. These products can be used for hedging and speculation, amplifying both returns and risks. High leverage and high volatility make them extremely dangerous for ordinary investors. Traditional financial markets have strict entry requirements for derivatives trading (exchange and clearinghouse licenses, etc.), but in recent years, a large number of crypto derivatives platforms have operated without licenses overseas, attracting global users. Regulatory agencies in different countries have varying attitudes towards this: some allow and regulate it, some restrict retail participation, and some completely prohibit it. This is one of the most direct manifestations of the differences in crypto market regulation.

The United States classifies Bitcoin, Ethereum, and other cryptocurrencies as commodities; therefore, their futures and options are commodity derivatives governed by the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA). The CFTC is the primary regulator, requiring any facility offering crypto derivatives trading to Americans to register with the CFTC as a Futures Exchange (DCM) or Swap Execution Facility (SEF), and brokers to register as Futures Commission Merchants (FCMs). Platforms and intermediaries must also comply with regulations regarding client asset protection and transaction reporting. To date, the US has approved a few compliant exchanges to offer crypto futures (such as Bitcoin futures on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) launched in 2017), but these markets primarily cater to institutional and professional investors, and trading volumes are relatively limited. The vast majority of retail investors prefer to access unregistered platforms (such as BitMEX and Binance in the past), which violates US law. The CFTC has been rigorously enforcing regulations against such platforms for several years: In 2021, the CFTC and FinCEN jointly penalized BitMEX for illegally providing trading services to the US and violating AML rules; in 2023, the CFTC sued Binance and its CEO, accusing them of circumventing US regulations for years, tacitly allowing US users to trade highly leveraged derivatives, and failing to fulfill their obligations to verify customer identities and monitor manipulation. These actions demonstrate that the US uses "offshore platform enforcement" as an important means of protecting its domestic investors. It's worth noting that the US also restricts retail participation in highly complex derivatives: for example, the SEC does not allow retail investors to purchase contracts for difference (CFDs) related to crypto assets or certain over-the-counter derivatives, and the CFTC has not promoted complex swaps to retail investors. Overall, the US model allows crypto derivatives, but trading must be conducted within a regulatory framework, and any attempt to circumvent regulations will be severely punished. This model is consistent with the US approach to other financial derivatives ("no permission is no law"). However, the SEC may also intervene in derivatives not included in the scope of commodities (such as options based on security tokens). For example, the SEC has warned certain platforms that offering swap contracts based on unregistered security tokens is potentially illegal. This demonstrates that the US assigns different regulatory responsibilities based on the nature of the underlying asset, but the core principle is that all derivatives require licensing, eliminating any room for regulatory arbitrage.

After assessing the risks of crypto derivatives to consumers, the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) announced in October 2020 a ban on the sale and distribution of any derivatives and ETNs referencing unregulated crypto assets to retail clients.[8][9] The ban, which came