Welcome to the 751 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since our last essay! Join 254,975 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday!

I’ve realized, writing this piece, that my job is to find and transmit a feeling.

When I first met Forrest Heath a year ago, I felt immediately that he was a special entrepreneur with the potential to build one of the world’s most important infrastructure empires.

Words are lossy, though. It’s taken me a year, a ton of conversations, even more research, a trip to Colombia, and over 33,000 words to put that feeling on paper.

This is my best attempt so far. The first, I expect, of many chapters in the story of Forrest Heath, Somos Internet, Autoridad Panandina, and the possibility of rebuilding the world’s infrastructure through vertical integration, lightness, and cashflow.

Let’s get to it.

If you want to jump straight to the online version: Read Cable Caballero Online

If you want it as a PDF, you can download it here: Cable Caballero PDF

If you want to listen on your Thanksgiving travel, I’ll have an audio version soon.

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Vanta

Of the many ways we will talk about how to grow a startup today, we won’t talk about compliance. Not because it’s not necessary. If you want to generate revenue at scale, it is. But because Vanta’s got it covered.

Vanta helps growing companies achieve compliance quickly and painlessly by automating 35+ frameworks, including SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, and more. Start with Vanta’s Compliance for Startups Bundle, which has checklists, case studies, and videos with industry leaders.

Get it here, and get back to the things you should be focused on.

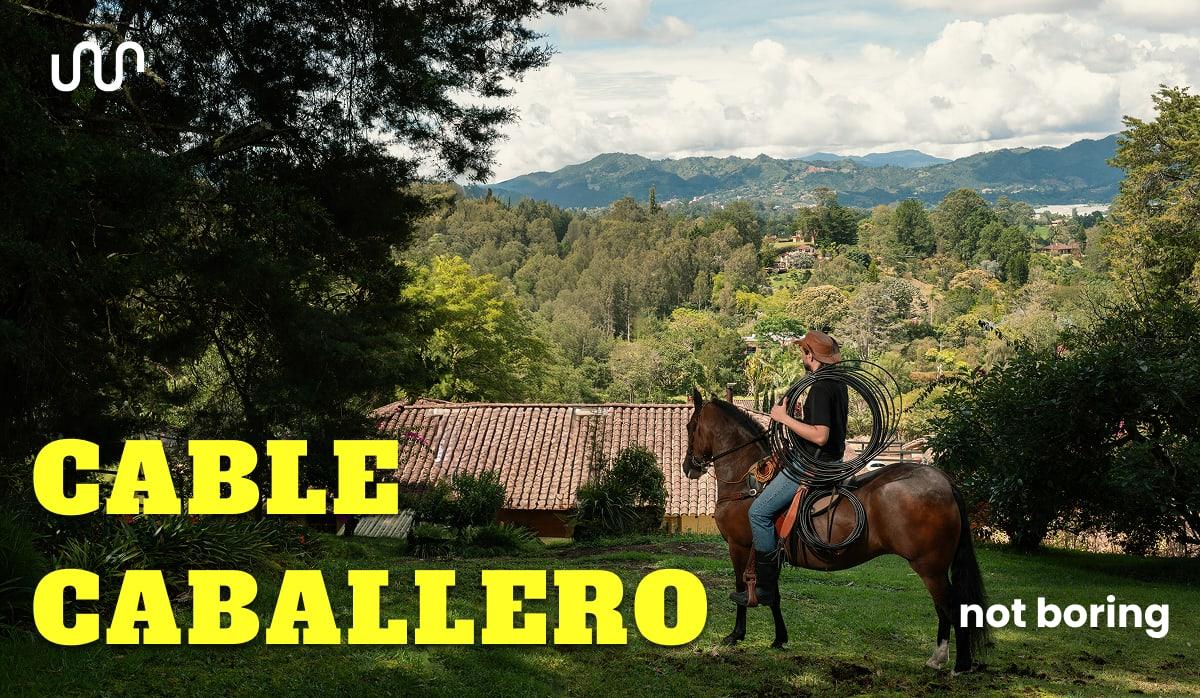

Cable Caballero

The hardest part of writing about Forrest Heath, III is figuring out where to start.

You might start in the backseat of a car, being driven, bag-over-head, through Medellín’s notoriously gangridden Comuna 13, to meet with the local “Duro,” “jefe de plaza,” or simply “gang leader,” about wiring up his comuna with better internet.

Record scratch, freeze frame, “Yep, that’s me. You’re probably wondering…”

Or in the passenger seat during Forrest’s frequent road trips, at age 16, from his home in rural North Carolina, 30 minutes outside of Chapel Hill, to visit his girlfriend in Washington, DC, just hoovering knowledge from audiobooks and podcasts at 3x speed as he sits in Beltway traffic, and actually retaining it, hanging each new piece of information in the right place on the growing scaffolding of his budding worldview.

I could bring you with me to a night in late August at the top of one of the hills surrounding Medellín (not one of the fancy ones, I’m told), where Forrest is hosting a BBQ for his team, his dad, and me on the bare concrete slab that will become the 15,000 square foot home that Forrest taught himself architecture and AutoCAD to design.

Better yet, join me in the front seat of his pickup truck as he rips up the windy, part-paved-part-dirt road to his casa, and back down afterwards, with his executives riding in the bed, drinking beers and laughing as Forrest intentionally hits potholes to bounce them around a bit. It’s all in good fun.

Or we might begin in Mexico City in October, at a gathering of powerful Latin American families, investors, policymakers, and entrepreneurs, sandwiched between Thursday’s Milken Conference and the weekend’s F1 Mexico City Grand Prix, where, upon arrival in t-shirt and sneakers (his nice shoes; normally he sports rainboots) he proceeds to captivate the former Vice President of Colombia with his observation that all energy, if you trace it back, is either fission power or fusion power. Later that evening, as attendees hobnob (as one does at these things), I find Forrest tucked away in the corner of a room off the courtyard, engrossed in an article about the United States’ plans to build an island off of Santa Monica “to launch Boeing’s 300-seat Mach 2.7 supersonic jet from two 15,000-foot runways.” “This is how I relax,” he laughed.

None of those vignettes capture the full story of the person I believe will come to be seen as one of the most exceptional entrepreneurs of this generation, a gringo who started what has become the third largest telco in Medellín and decided, while growing that business, both within existing markets and to new ones, to start a second business building data centers attached to hydroelectric power plants (Colombia’s mountains produce incredibly cheap power; it’s transmission that’s the problem), and convinced two of America’s best venture firms to back them both, though, if it’s even possible to capture. I will certainly try my best.

And the best place to start, I think, is the first time I met Forrest Heath, III, for a thirty minute coffee that became a three-and-a-half hour whirlwind at Public Records in Brooklyn, at the end of which I agreed to commit the first slug of what I hope to be many tens of millions of American Dollars to the Cable Caballero with a master plan to build a vertically integrated infrastructure empire.

A Forrest Comes to Brooklyn

“Man, your Vertical Integrators series has made it so much easier to pitch Somos to VCs,” was the first thing Forrest said to me when all six foot five in rain boots of him strode into Public Records, carrying a big backpack and vibrating from what I would learn is a Gulliverian amount of daily coffee consumption.

(“I’m like a coffeed-up golden retriever that just likes tinkering and building stuff,” he told me later, once we knew each other well enough for him to compare himself to a dog.)

We sat down and ordered more coffee and I started buzzing, too. Hearing Forrest explain Somos was like watching those essays on Vertical Integrators come to life sporting a mustache and ponytail.

The idea behind Vertical Integrators is straightforward. We have better technology today than we did when the dominant incumbents in physical industries were born. They have too much invested in the old architecture to completely rebuild with new technology, so startups can build fresh with modern technology to create products that are better, faster, cheaper than incumbents’, at higher margins. Startups, then, should be able to compete directly and win, build bigger businesses, even, than the incumbents they replace.

When I wrote those essays, I didn’t have telcos in mind. I thought they were too deeply entrenched, often literally, and that the CapEx required to compete would be far too heavy a burden for any startup to bear.

Cable Cowboy, Mark Robichaux’s biography of TCI and Liberty Media CEO John Malone, is one of my favorite business books of all-time. It’s basically the story of the insane and harrowing financial engineering required to wire up the world. Initially a small and fragmented industry driven by actual cowboys who just wanted to pull a TV signal for their rural communities, telcos had consolidated to the point that only a few giants - Comcast, Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, and Charter/Spectrum - survived.

In his new autobiography, a recently-released first-person version of Cable Cowboy called Born to Be Wired, Malone explained the logic:

It was all quite simple—a virtuous cycle that would help us gain the advantages of scale economics. Buying more cable systems would bring in more paying subscribers. More paying customers meant higher cash flow and lower costs in the form of bulk discounts for networks. Increased cash flow allowed TCI to borrow more money and pay the higher total interest costs on it, which we used to buy still more cable systems.

And, like, what is a startup going to do there? Come up with a cheaper way to build physical infrastructure?

Yes, Forrest explained. Exactly.

Over the next 210 minutes, interspersed with thoughts on the right way to build nuclear, praise for Ian Brooke’s skill as an engineer, and novel theories on the US-China relationship, Forrest laid out a vision for what Somos would become with a combination of clarity, depth, and energy that I’ve come to see as his signature style.

The High-Level Pitch for the Forrest Infrastructure Universe (FIU)

This is the gist of the pitch Forrest gave me at Public Records.

Somos is a vertically-integrated infrastructure company whose first product is internet in Medellín, Colombia.

It is not a traditional challenger Internet Service Provider (ISP). Most challenger ISPs are just wrappers on someone else’s infrastructure, basically marketing companies. They’re low CapEx, because they don’t build much, but low margin, because they have to pay to their infra providers and equipment suppliers. Crucially, they don’t make the internet fundamentally better or cheaper, because to do that, you have to rebuild the whole stack.

Even the traditional telcos, the ones who build, own, and maintain the networks, kind of suck. They have $0 R&D line items. They outsource their research and development to vendors like Huawei, Juniper, Cisco, and Nokia, and get stuck paying ever-higher prices for network hardware when they have to make upgrades every few years. They are high gross margin businesses with recurring revenue, but they have to dump those margins back into CapEx in a never-ending race against decay and growing customer demands.

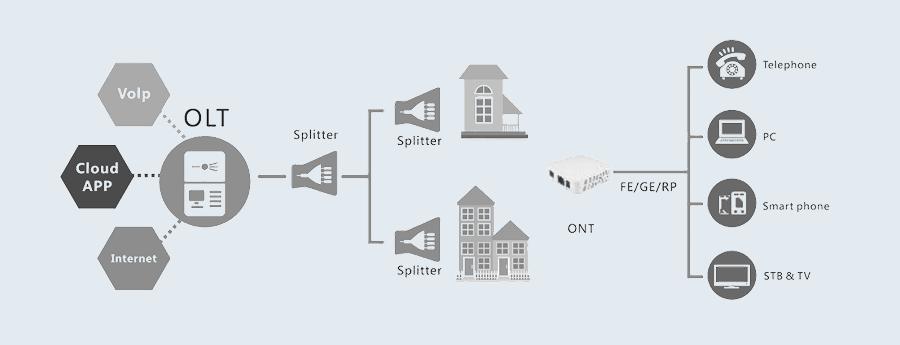

Plus, their PON (Passive Optical Network) network architecture – so named because it uses passive optical splitters to share bandwidth among multiple users – means that they need to decide how many users split each fiber connection upfront, and locks them into both the architecture and vendors because of OLT (Optical Line Terminal) and ONT (Optical Network Terminal) compatibility, which is why changing anything is so expensive.

Competing with telcos at their own game, or building on top of them, is a losing proposition. They have too much financial muscle. Competing with them by playing a new game, however, could actually work. They have atrophied engineering muscles. They’re sitting ducks.

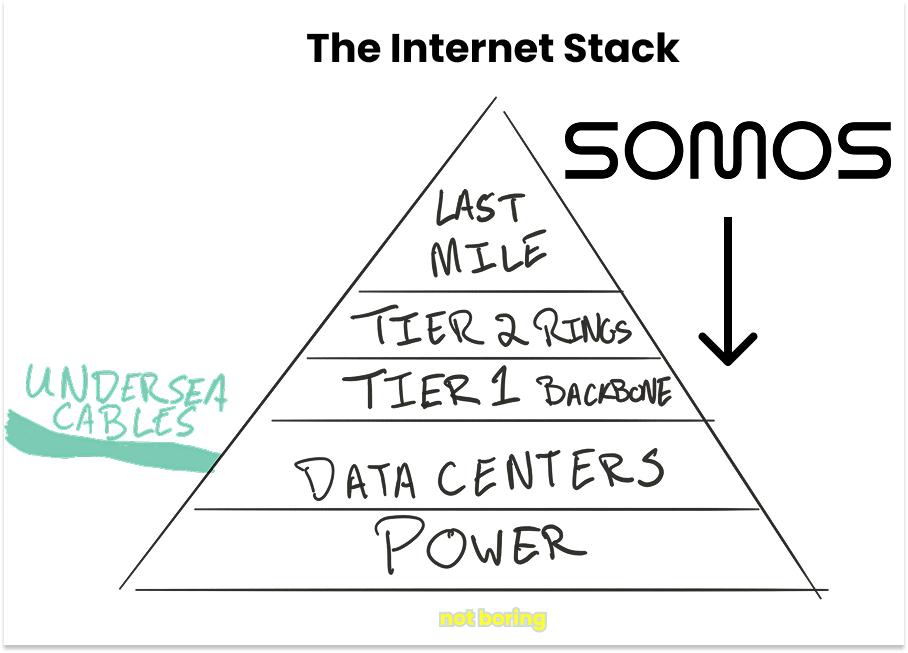

Somos is building a vertically-integrated internet network, rebuilding the full stack from fiber infrastructure all the way to custom routers and the software that manages it all.

It is building a network based on an Active Ethernet architecture borrowed from data centers. We will go into the details, but the easiest way to think about it is this: whereas traditional telecommunications networks are physically complex, requiring expensive hardware that needs to be upgraded every 3-5 years, Somos’ network is physically simple and pushes complexity to software.

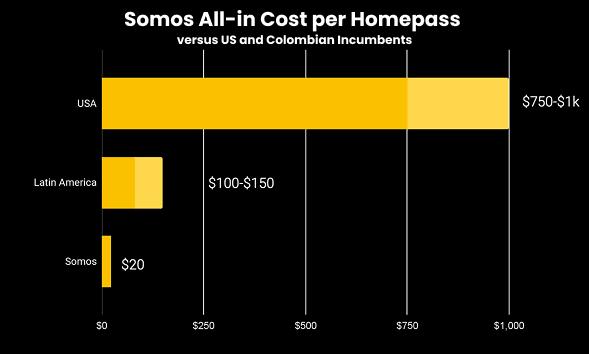

What that means practically is that Somos is currently spending $20 of CapEx per homepass (the cost to build out network infrastructure to reach a potential customer, whether or not they actually subscribe to the service), $7 for hardware and $13 for labor. Incumbents in Colombia pay $100 per homepass in dense urban areas, and incumbents in the US pay $500-1,000.

Incumbents not only pay more, they pay more for worse networks. Part of the reason Colombia is cheaper than the US is that Colombian telcos split their optical signals among 128 or more customers, versus 32 in the US. CapEx per homepass goes down at the expense of building a meaningfully worse network.

Because of its structurally superior cost structure and network architecture, Somos can offer a better product (1-2 Gbps low-latency, redundant internet) at a lower price (as low as $8/month). Because it makes its own hardware, and writes its own software and firmware, it is able to understand its network in a way that no incumbent can, and fix issues more quickly. The network improves as it grows, which is unique to the architecture, and is cheap and easy to upgrade.

Financially, all of that means that Somos can generate those same high gross margins on sticky recurring revenue (it ended Q3 2025 with 77% gross margins, and will grow them to ~90% in the next couple of years), but with CapEx paybacks of 14-18 months, and upgrades that only require swapping out switches and laser modules that are cheap and getting cheaper.

That leaves Somos with high-margin recurring cashflow and happy customers. It can reinvest the cashflow into growth, lower prices, R&D, or new infrastructure and products. It can reinvest the customer loyalty into increasing margins and ARPU as it sells them more products on top of the infrastructure it’s built right into their homes.

One thing that Somos might do, Forrest said then, is to build its own power generation capabilities. Colombia’s mountains and rainfall create high head pressure that is perfect for hydroelectric power. In fact, 70% of Colombia’s power is hydro, but there should be a lot more of it; the challenge is, like it is in the US, that transmission is slow and expensive to build. But Somos is getting really good at building the infrastructure to transmit bits over long and short distances; why not electrons?

Of course, none of this is limited to Colombia, because infrastructure is old and shitty everywhere. It can be made better, faster, cheaper, and higher-margin all around the world.

Medellín was just a great place to start because of how bad the alternatives are, how strong the talent pool is, how much easier it is to build, how dense it is, and how rich the hydro resources in the surrounding areas are. Somos is already in Bogotá now, too, and it will begin its expansion throughout LatAm next year.

First internet, then power. The substrates of the modern world. First Colombia, then everywhere.

What I want to get across here but am having a hard time conveying in its totality is how well everything fits together: the network architecture, the financial architecture, the organizational architecture, and the ethos.

“It’s been this never-ending game of doing something janky, getting credibility, doing crazier stuff, getting more resources, getting smarter people so that we can fix the things that were messed up in the janky past iteration,” Forrest explained. “Then gaining credibility to get more resources to get cooler people to do crazier stuff. It’s like this self-sustaining fission process.”

The technical architecture enables the talent architecture. Because Somos builds on open standards rather than proprietary systems, it can constantly upgrade individual pieces of the system without breaking everything. If someone smart comes in and says “we should actually be building the network on fiber instead of radio links,” which is something that happened, it can do that. “You get the benefits of vertical integration without needing everything to talk the exact same protocol.”

Somos is a machine designed to last and adapt for a long time, this weird combination of complete clarity of vision with total humility on exactly what it will take to get there.

And if you think about it, the things such a machine should be able to build are limitless: if you finance the business correctly, generate cashflow, and build a team of pirates who are great at building high-quality, tech-enabled infrastructure cheaply and quickly, why stop at internet and power?

What would a modern Bell Labs look like, if you put it in the hands of a band of hypercompetent technical misfits like Somos’ instead of next to a stodgy, regulated monopoly like AT&T?

Why shouldn’t LatAm have better infrastructure than the United States within the first half of the century?

The challenge, he predicted, would be entropy. Corporate entropy, of course. AT&T was young and scrappy once, too. But also the entropy that comes with building large physical networks.

“Telco is this high entropy system. There’s this entropy horse, and you’re riding the entropy horse,” he said, Forrestly. “The legacy telcos have gotten bucked off the entropy horse. My job is to keep us moving fast enough that we don’t get bucked off the entropy horse.”

Which sounds like exactly the job for a Cable Caballero.

I haven’t been in venture for that long, just five years, but it felt like a once-in-a-career opportunity to back a business with a practically boundless market (infrastructure) led by a founder who struck me as the best systems thinker I’d ever met. As I wrote an LP the next day, explaining why I had invested in a Colombian telco after one very long coffee and exactly zero post-meeting due diligence:

Time will tell if this was smart or whether Somos is just overfit to my thesis, but I’m really excited about this one. It’s a better product at structurally lower costs and higher margins in a massive industry that spits off a ton of cashflow, which I think Forrest will put to work well. It’s exactly the kind of business and founder I want to back.

So I invested on a SAFE ahead of what I expected to be a wildly competitive Series A-1 just to make sure that I defended my allocation from who I expected to be ravenous investors.

Then, over the next two months, no one invested in Somos.

How to Grow a Forrest

When I asked Nico Berman, the Kaszek partner who has backed Somos since the beginning, why he thinks it was so challenging for Somos to raise the A-1, he got quiet, thought for a few seconds, and then started smiling like he knew he had a banger on his tongue. He did.

“I think that people were focused on the trees, and missed the Forrest.”

“For you not to decide to invest in a company, there are always a thousand excuses you can make,” he said, before listing some of the Somos-specific ones. “It’s just in Colombia. It’s hardware. Worse, it’s hardware integration. It requires some debt to expand.”

Up against all of those very real trees, though, there was a Forrest.

And to understand why everything else I write in this piece isn’t insane, why it might actually be possible to build a better telco in Colombia, take it throughout LatAm, and then maybe to Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia, even the United States of America, compete with incumbents who will happily spend billions of dollars on capex each year, beat them by offering a better product at a lower cost, and do all of that both because cheaper infrastructure causes disinflation, which is the only sustainable way to drive abundance, and also just to generate the cash flow with which to build even more infrastructure – hydroelectric plants, data centers, metro cables, a new grid, whatever – better and cheaper, to cause even more disinflation and therefore abundance and to accumulate more resources - people, talent, capital, connections to homes, customer loyalty - to just keep playing the game until everything is better and cheaper and works more closely to what the physics suggest they could or until you die, whichever comes first, you need to understand that there is almost no one like Forrest, and you could, of course skip all of this biography, move straight to what Forrest is building today, because it will be a little long, but then you’d be making the same mistake they did, wouldn’t you?

Fast-forward.

It’s August 2025, nine months after I met Forrest at Public Records. It’s early: 6:30am. I walk out of my hotel to meet Forrest Heath III, who’s picking me up in his pickup truck to go check out a hydroelectric generation site in Medellín. There’s someone I’ve never met in the passenger seat, so I hop in the back, and the guy in the front turns around and introduces himself with a slight North Carolina drawl. “Hi, I’m Forrest.” Forrest Heath II, specifically, Forrest III’s dad.

III hadn’t told me II was in town - there’s always just a lot happening around III, like one of those one-shot films - but as someone writing a profile on the son, the father’s presence was a gift. He probably knew the answer to the question I’d been trying to figure out: how do you grow a Forrest?

Rewind.

Forrest Heath III grew up right outside of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where his dad was, and is, a municipal engineer. Whether through nature or nurture, the engineering passed from father to son.

“Forrest was a very curious kid,” Forrest II told me, when I asked how he’d created… that, “just always asking ‘Why?’ One of the things we did was just always answer him like an adult. Another was, we had a room full of Rokenbok, and he would spend all day in there building the most elaborate structures.”

Some structures, though, were too big for one big kid to build alone. During the summers, the Heaths decamped to the Outer Banks, where instead of fighting Kooks for the Royal Merchant’s gold, Forrest just wanted to dig really big holes.

“When I would go to the beach, I would show up with, like, actual shovels and shit, and tarps, like real construction materials,” Forrest remembered.

I’d spend the first couple hours going around recruiting other kids to basically be on my labor gang to go build canals. I’d spend the first couple of minutes digging a really deep hole by myself, and then I’d bring the kids there and be like, ‘Yo, look how deep my hole is. Do you guys want to help me make a bigger one?’ It was a little bit like, you’ve got to get the initial traction and proof points before you can get the more serious resources and capital behind you.

We actually had the Park Rangers come to us because we were changing the erosion patterns of the beach because we built these crazy waterworks over the course of the week.

There’s a goal-directedness about Forrest that’s been there since as long as he can remember. Pick something crazy to do, be 100% certain that you’re going to be able to do it, and then figure out how the hell to actually pull it off along the way.

(“Did he tell you about his triathlon days?” Ross Garlick, Somos’ CFO, asked me when we were texting about this section. I said he hadn’t. “Just that he was a competitive triathlete at the state level until age 13/14, had an accident (I think), and never competed again. Not sure it makes the piece, but it’s just that the guy has already lived many, many lives.”)

((“2nd in the country,” Forrest corrected us. “It was a USA Triathlon points system based on times and races. I did a mostly sprint distance. I was homeschooled so I could train 5 hours a day with a professional team. Basically from ages 9-13, that was my obsession.” What was the injury? “Stress fracture in my ankle. Basically training too hard and my bones were growing wrong, so either quit cold turkey or risk being a cripple when I was 30.”))

The world, through Forrest’s eyes, is hackable.

So when he learned about North Carolina’s “Middle College” program in seventh grade, a program that allows North Carolinians to simultaneously take courses for high school and college credits in order to get an associate’s degree alongside a high school diploma, “Forrest was so excited,” his dad told me, as the pickup drove back down the mountain. “The two of us spent the summer learning Algebra 1 together – I needed to re-learn some of it to teach him – to prepare.”

To hear Forrest tell it, “I distinctly remember being in middle school when they came to talk about it, and I broke out a piece of paper to take notes and went up to talk to the guy afterwards.”

Turns out, you could take a bunch of classes that count for both high school and college credits, so starting in seventh grade, Forrest took summer classes to get through the pre-requisites, started Middle College at 14, took classes from 8am to 9pm Tuesday and Wednesday so he could be in Washington, D.C. the rest of the week, and almost got his associate’s degree at 16…

But I was missing one biology credit. I kind of just made this executive decision that I wasn’t gonna finish that biology credit. So I think technically, I’m, like, one credit shy of both a high school diploma and an associate’s degree that I finished at, like, 16.

Then there’s something he didn’t say, but which I find interesting. Middle College is an excellent program for people who want to get their degrees quickly and affordably. It gets you college for free. But it wasn’t necessarily for superstar students, the ones who would want to travel 30 minutes down the road to the greatest college in the country (in my opinion), or up north or out west to some other great ones, when the time for real college came. Talk to Forrest for ~20 seconds and you realize that he could easily have attended one of those schools.

But he didn’t, and not for lack of worldliness or ambition. This is a video of 15-year-old Forrest giving a TedX talk at the time, on the idea that electric cars needed to stop selling on environmentalism and start selling on performance. He was at least half a decade early to that insight.

But Forrest didn’t complete his associates degree at the age of seventeen, or sixteen. He was missing that biology credit, and somewhere on one of those drives back and forth between North Carolina and Washington, D.C., he decided that he just didn’t need it.

It has become fashionable to get into Stanford, and then drop out to start a company. It is basically a no-risk path; getting in is the important part. It is, and was then, too, less advisable to drop out of Middle College, one credit short of even a high school degree. It took real balls, or a healthy disregard for systems that made little sense as currently constructed, or both, and besides, Forrest was never going to work for anyone else, so why worry about a piece of paper? D.C. was home to a girl who, in that moment, was more important than a degree, and to the politicians who were going to help Forrest build the high-speed train line he wanted to build: SouthRail.

(Anyway, as he told me in our first conversation, most of what he learned he learned by listening to audiobooks and podcasts at 3x speeds on those drives from NC to D.C., and D.C. to NC.)

“So from 16 to moving to Colombia, what was that period?” I asked him, having just uncovered another YouTube deep cut from the year after the first. “You start this other company trying to build high-speed rail that I didn’t know about until now…”

“Yeah. Well, in that intermediary period, this was right when Brightline in Florida was first talking about the stuff they were doing…”

So I got really excited about the idea of public-private high speed rail lines. I built this whole concept called SouthRail, where I was effectively trying to pitch the North Carolina government to go apply for a couple billion dollars of loans from the Department of Transportation. And the idea was North Carolina is one of these very rare places in the US where the state government owns the right of way and they lease it to the freight operators. So it’s kind of like the Northeast corridor, where it’s, it’s not just entirely owned by the freight companies, which makes passenger service really complicated to do.

The pitch was like, look, you guys have this incredible asset between Charlotte and Raleigh Durham, which are two of the fastest growing places in the entire US. I-40, the highway was like very constrained and they already had this right of way that was quite straight went through the downtowns of all of these locations and with a few billion dollars could go from being like a decent-ish, sort of like local train system to kind of effectively what Brightline built, but with higher density, less grade crossings.

There’d already been a bottom-up program that had done some improvements. So the idea was sort of like, what if we doubled down on this and, critically, I became super obsessed with the Japanese and Hong Kong MTR [Mass Transit Railway] kind of model of financing. Transit improvements with real estate development.

This is one of the saddest things that we stopped doing in the US. It’s like, you go to Japan. All of the transit basically is operated more or less at break even because JR East and all the railroad companies make so much money on their rentals of their super dense malls and apartment complexes and buildings they built around. And it’s like we sort of treat public transit as if it has to be this magical thing that somehow invents its own operating budget. But if we used it as a thing in a combined system where you’re developing land and building transit to it to make the land more valuable, it’s like you’re directly capturing the upside in a way that is super obvious. But we don’t do it in the US.

“I mean, what you’re doing with your house and the Metrocable is essentially following that exact model,” I added, referring to the fact that he bought a plot of land on the top of a mountain on the cheap, taught himself CAD and architecture, and has been building a 15,000 square foot house / guest lodge / maker space, with the idea being that, in the not so distant future, he will buy land at the bottom of the hill and some more at the top, build a Metrocable, and in so doing, will make his commute more convenient and his property more valuable.

Yeah. But. It’s kind of like the idea basically, was that there was so much land that the state owned around the rail corridor that they could build these crazy, dense developments, and that would be a massive funding source for the whole thing.

So I convinced the state government to let me go, kind of work on their behalf. I was like this 18 year old kid showing up in D.C. being like, ‘So we want to raise a couple billion dollars to go finance this thing. The Governor kind of sort of sent me here. I have no official position, like I’m just a random person, but, like, here’s the email from the Governor saying, like, ‘Sure, if you go ask them, we’ll support you.’’ Then North Carolina’s Congress changed and it kind of became politically unviable, unfortunately. But like, we were pretty far down the analysis path and I learned a lot about transit development there.

So yeah, that was my intermission in trying to build a railroad.

So that was what Forrest did instead of finishing high school, and I’ll tell you in a second what he did instead of going to a traditional college, but in addition to the things that he did do, when I asked Forrest III what made Forrest III Forrest III, what he didn’t do was just as important.

“I’d say the thing I’m grateful for, and I don’t really have the ability to take much credit for it, is just somehow I never lost my innate childhood curiosity,” he said…

And I think this is something that I like, when I met your kids and they’re just playing around and imagining stuff on the playground in Brooklyn, it’s like, everyone was kind of like that at some point, right? Like, almost all of us had some way we were playing with imaginary forts and imagining a future that didn’t exist or imagining a world that didn’t exist and kind of putting our headspace into it.

And I think for some weird reason—both me being kind of stubborn and a bit skeptical of a bunch of different things, and honestly, I think just random chance—I never got that beaten out of me. And I kind of was always, like, finding my own weird path to sort of come at stuff.

Tangentially, that meant that I wasn’t really competing against the system of, ‘Get higher SAT stores, get into the right college and, check all the right checkboxes.’ And I think there’s this sort of, like, innate builder kind of curiosity in me that I never lost. If anything, I’ve kind of compounded it.

So when Southrail died, Forrest just kept exploring. Instead of going back to school, he had “a brief intermission in Tallinn, Estonia for 4-ish months” with a friend, a result of the duo convincing some Chinese investors to give them some money to go and write a report on the Estonian startup market.

“We basically just showed up and didn’t know anybody,” he recalls, “so we started going on Eventbrite to find random events. We found one that was called the Tallinn Digital Summit, and I couldn’t figure out how to sign up, so I just put in the website of my website design firm and basically applied for press credentials.”

Two weeks later, the two American teens got an email saying, basically, “You’ve been accredited as an EU journalist.” Which was the perfect thing to be in that place at that time, because unbeknownst to the Americans, Tallinn had the EU Presidency at the time, and the Tallinn Digital Summit wasn’t just a random local event but the place upon which many of Europe’s leaders were descending:

So we go to this gala the first night, a celebration of entrepreneurship in the EU, and in this really weird way, we sort of stumbled into actually doing what we were supposed to do, but we’re sitting there and it’s like Chinese State Media, French State Media, like Turkish State Media, France24, and like The New York Times, and they just find it hilarious that these two 18-year-old kids are there with official credentials, so we kind of befriend the whole press corps.

We’re kind of just there. We go to all of these events. And basically we ended up going to this press conference for [French President Emmanuel] Macron. My friend spoke a little bit of French, so basically we snuck into that conference, and then very, very long story short, we basically befriended the Chief of Staff lady of the French delegation because they realized that we were neither French nor reporters, but they thought it was hilarious that we were there.

And then a few weeks later, there was basically this delegation from Armenia that we befriended and ended up going with them to this state gala at the President of Estonia’s house and very, very, very long story short ended up basically partying with all the EU leaders. It was a fucking wild time for an 18-year-old.

“And I think this was one of the most formative periods for me. It was just sort of the moment of realizing that you can show up and do stuff. Not that there are no rules, but like people create all these blockers that don’t really exist, and you can kind of just figure stuff out. And as long as you’re curious and well-intentioned and not causing harm to anybody, you can kind of go and basically do almost anything.”

In a classic blog post, Marc Andreessen wrote, “The world is a very malleable place. If you know what you want, and you go for it with maximum energy and drive and passion, the world will often reconfigure itself around you much more quickly and easily than you would think.” And I nod along passively every time I see the quote pop up, but it doesn’t feel that malleable to me. I’ve viewed it as an inspiring metaphor.

Spending time with Forrest, and hearing him tell his story, is how I realized that Marc meant it literally. I tell Forrest that.

“Yeah,” he says, “I have this very Forrest Gumpy approach, just, like, stumbling into random shit in life. It’s very funny, the parallels not just in name but also in the ability to stumble into random interesting things.” And places.

Like Colombia, where his friend from Estonia went next, to teach English, and where Forrest, whose lease was ending in D.C., went to visit him, fell in love with the place, got roped into helping some guys do “this blockchain, incentivized mesh thing in the slums and kind of quickly realized that nobody wanted this blockchain stuff, they just wanted cheap, fast internet,” didn’t know any Spanish, but slowly learned it, and didn’t know anything about network engineering, but learned that, too, decided to stay and build the best internet network anywhere in the world, starting in the slums, which is how he ended up in the backseat of that car with a bag over his head on his way to meet the jefe.

A Very Brief Overview of Existing Telco Networks

Forrest didn’t know jack shit about internet infrastructure when he moved to Colombia, but he wanted to build internet infrastructure, so he had to learn, and from that particular perspective – needing to actually build the thing with no prior knowledge – he noticed that the internet was not built like you’d built the internet today.

Telcos are legacy systems locked in an old network architecture that made sense at the time, but no longer does.

They do practically zero R&D; look at the R&D line items of your favorite telco like AT&T or Comcast if you don’t believe me. Instead, they buy network equipment, and the software that goes with it, from network equipment providers (NEPs) like Juniper, Cisco, Nokia, or Huawei, and they get locked in. Every few years, when they need to upgrade their network equipment, they spend billions of dollars on whatever the NEPs tell them to buy.

You can think of the internet flowing through undersea cables to Internet Connection Points (data centers or “IXPs”), Tier 1 “backbone” providers like Cogent and Lumen to Tier 2 middlemen who build regional fiber rings and charge local ISPs like whoever you’re buying internet from right now. Some large ISPs with enough traffic to justify the cost will connect directly with the Tier 1 providers; otherwise, they have to pay a toll to the Tier 2s.

Then comes the hard part: the last mile, from the ISP’s neighborhood fiber into your home.

The last mile internet architecture is a vestige of the Cable Cowboy days.

When the internet hit, these guys had already spent tens of billions of dollars building out higher-bandwidth one-way cable and lower-bandwidth two-way telephone networks in a tree-and-branch topology, so they decided to stick with that shape and swap the cable and copper for fiber.

“As far as bandwidth goes,” Cable Cowboy John Malone writes in Born To Be Wired, “their twisted pair of copper lines was a drinking straw compared to the firehose of hybrid fiber-coax. But they [the telephone companies] were putting more fiber into their networks, overlaying their thin twisted copper. And they could do it easily, with plenty of capital and deep experience in switched, two-way communications.”

When fiber optic cables became cheap enough in the early 2000s, the industry began replacing copper with glass. Fiber can carry dramatically more data, theoretically unlimited bandwidth over a single strand of glass thinner than a human hair. But the economics of running dedicated fiber to every home still didn’t work. Installing fiber is expensive. Digging trenches, stringing cables, obtaining permits, navigating buildings… it all adds up.

So in the early 2000s, the industry kept their underlying architecture, added fiber, and modified it to create the network architecture they’re stuck with today: Gigabit Passive Optical Network, or GPON.

In a GPON, one fiber leaves the ISP’s Optical Line Terminal (OLT) until it hits a splitter (just a special piece of glass that splits the signal into 16, 32, 64, 128, or even 256 weaker beams), travels on to the final destination, and hits the Optical Network Terminal (ONT), which converts the light in the fiber back into electrical signals.

This creates a whole bunch of problems, for you the customer and for the ISPs.

For you, the architecture means that you’re sharing the bandwidth with your neighbors (which is why your internet slows down when everyone watches Netflix at 8pm) and that you’re stuck sharing with them, because you’re locked into whatever split ratio the ISP chose when they built the network years ago.

For the ISP, upgrading the network means physically replacing expensive hardware, like ONTs and OLTs, by buying new stuff from vendors, who know they have you over a barrel because Huawei stuff works best with Huawei stuff and Juniper stuff works best with Juniper stuff, and you’re using their software anyway because you didn’t write your own. So every few years, ISPs have no choice but to pay up for equipment that pushes more bandwidth through the same split fiber, and they almost never change the split ratios because while the splitters themselves are cheap (they’re just glass), it’s labor intensive to find the thousands of them distributed across the city, climb poles, dig into underground vaults, and replace them, and because GPON is a tree and branch architecture with no architectural redundancy, doing so risks bringing down the internet for every home on that splitter or breaking something bigger in the old, creaky architecture.

Sorry, that actually makes it sound easier than it is. I haven’t accounted for entropy. Incumbents suffer from documentation drift over the years because, with a passive architecture, they can’t really understand or validate their network downstream from the OLT until they get to the ONT. Plus, today’s networks are hodgepodge Frankenstein mashups from all of the Malone-era M&A. So in many cases, no one actually even knows where all the splitters even are (!!) until they field verify, which is in itself labor intensive and expensive!

The upshot is: incumbents are deeply, deeply stuck, to the tune of tens of billions of dollars and a lack of modern technical talent, anyway, in this old architecture, and new entrants can’t really do anything to fix the current system, because it’s the whole system that’s sclerotic, not any one component. Challenger ISPs are equally unattractive; essentially marketing companies that have to pay tolls to every layer of the stack, they’re not venture-scale businesses.

All of this is why, before I met Forrest, I thought that my Vertical Integrator thesis didn’t extend as far down into the infrastructure layer as telco networks, and what you’re about to read is why, after I met Forrest, I believe it’s the best system for a Vertical Integrator to attack.

Curve Convergence

In August 2024, a few months before we’d met, Somos CFO Ross Garlick sat down to write a “Not Boring style breakdown” of Somos, in which he wrote, “Getting Packy down to Colombia to spend some time with us and write the Not Boring piece is one path that we haven’t ruled out yet, but I decided I’d give it a go myself.”

I just found that out when he shared a bunch of materials with me for this piece, and it makes me very happy. But the reason I bring it up now that I’m writing the Not Boring piece is because in it, he wrote about Somos’ mission, and why Forrest chose to start the path towards it with internet.

Somos Internet is on a mission to cause deflation in fundamental infrastructure, beginning with connectivity…

When I asked Forrest why he chose to tackle telecommunications instead of energy or transport, his answer formed the basis of the moat that Somos is currently digging: telco was the only fundamental industry Forrest saw with exponential cost-performance curves (think Moore’s law for Internet) that hadn’t been fully developed.

In discussing how Somos is building its network, we will discuss a number of architectural choices, but this is the meta-architectural choice: design a network in such a way that it rides exponential cost-performance curves.

This will come up over and over again. Radio link costs. Router component costs. Ethernet switch costs. Fiber costs.

Forrest explains it like this: “If you move everything to ethernet switching, you move from expensive, low-volume proprietary units to stuff doing billions of units, so the cost per bit falls to nothing.”

As the computer industry has taken full advantage of, and as we argued in The Electric Slide, “the curves are destiny.” A network whose curves have stopped curving will decay. A network that rides the curves will continue to improve.

The more I’ve thought about it, the more I think this is an as-yet-unnamed category of disruption that Somos exemplifies. It’s something that I’ve been gesturing towards in a number of essays - the Vertical Integrator Series, Better Tools, Bigger Companies, I, Exponential, and The Electric Slide - that studying Somos in depth has crystallized.

Call it Curve Convergence: when multiple component technologies improve on exponential curves while industry architectures remain frozen around outdated assumptions, creating the opportunity for disruption with a better product.

Unlike Christensenian low-end disruption, where new entrants start with inferior products that improve over time, Curve Convergence creates immediate competitive advantage (immediate meaning “as soon as the new system is built”). There are a few reasons that this type of head-on disruption is possible.

First, whereas low-end disruption requires a company to integrate a new component into a product that undershoots the mass market but serves an underserved niche in order to pull that component onto its own cost-performance curve, the component technologies involved in Curve Convergence are already on cost-performance curves thanks to their use in different industries. Batteries, electric motors, power electronics, and embedded compute all got cheap and powerful enough in different applications that drones suddenly became possible. These are exogenous curves.

Second, because Curve Convergence disruptors face incumbents that have built systems, like telcos, instead of single products, like hard-disk drive manufacturers, those competitors typically can’t take advantage of individual now-cheap-and-performant components without rearchitecting their entire system.

When industries design their architectures, they encode assumptions about what’s expensive, what’s possible, and how systems should be structured given available technology and resources. But as underlying components improve exponentially (following Moore’s Law, Wright’s Law, or other cost-performance curves) those architectural assumptions become increasingly obsolete. The components improve while the architecture stays frozen in time. This creates an opportunity to rebuild entire systems not incrementally, but with fundamentally superior economics and performance from day one.

Third, there is something like a requisite amount of difficulty in disruption. In low-end disruption, much of the difficulty comes from needing to start in a part of the market that seems too small or “like a toy” and battling to move upmarket over time before incumbents react. In Curve Convergence disruption, most of the difficulty comes from the fact that you need to vertically integrate to reap the benefits of multiple curves.

The bottleneck isn’t technology readiness, because the components exist and are proven. They are being used and scaled in other contexts. The bottleneck is the vertical integration execution required to actually rebuild the stack, combined with the fact that incumbents remain rationally committed to optimizing their existing architecture rather than abandoning decades of investment. They continue making incremental improvements to legacy systems because changing the architecture would require write-offs, new capabilities, and organizational transformation that makes no sense given their installed base and expertise.

Architectural convergence requires seeing across multiple component curves simultaneously, understanding which assumptions encoded in incumbent architectures are now obsolete, and recognizing that multiple curves have matured enough to make entirely new system designs viable today.

One of the questions I get asked most frequently by LPs is whether I have theses on specific categories I’d like to invest in. My answer is an unsatisfactory “no.” I haven’t put my finger on why until now, and it’s this: it is very easy to spot one technology shift and imagine what might change because of it. “We have AI now, so I’m looking for AI doctors.” But those are so obvious that an investor can come up with them, which means they’re certainly obvious for enough founders to build them, which means tons of competition, bad margins, and uncertain outcomes. It takes obsessive dedication to solving a particular problem to spot a Curve Convergence early enough to build a generational company on top of it, which is a luxury available only to founders, not investors. So I prefer to be led into opportunities by founders like Forrest.

Because there’s just no way I could have seen that things like smartphone chips getting good enough to be used in radios would open up the opportunity to build a Vertical Integrator in wired telecommunications.

Starting Somos

GPON is the way the internet worked basically everywhere in the world when Forrest started teaching himself network architecture in Medellín’s barrios populares, its poorest neighborhoods, the ones to which it didn’t make economic sense to bring the internet.

“When I met Forrest, one of the things I respected was that he was actually living in the barrios populares, despite the difficulty,” Daniel Vasquez, who was the second investor in Somos after K50, where he’s now a partner, told me. “He didn’t care about comfort. He just wanted to build.”

(Not just living there, facing down the Duro, too. Turns out, he basically wanted to know this tall white guy wasn’t a cop, and when Somos brought pastries, acted like a normal dude, and offered him free internet, the Duro was happy to have him in the Comuna.)

Economically, though, the internet just didn’t work where Forrest lived. It was simply too expensive to dig up the streets to lay cables and buy expensive network equipment from Juniper and Cisco, relative to what his customers would be able to pay.

But, start with the end goal: deliver cheap, fast, reliable internet. Normally, that meant GPON, but it didn’t have to, right?

Compared to the incumbents, Forrest had a ton of disadvantages. He had practically no money, for one, didn’t speak the language, for another, and was literally living in the slums, for a third.

But he had a couple of advantages, too.

The first advantage Forrest had was constraints. Because he couldn’t afford to lay cable and buy expensive network equipment, he had to get creative.

The thing that you hear over and over again talking to the people around Forrest is that he is a very “first principles” thinker. That is now a dramatically overused phrase that nonetheless applies perfectly to Forrest.

For example, the cheapest cable, from first principles, is no cable. So what about using radios?

Radios had always been too expensive to build internet networks on because they were produced in low volumes and required custom chips. These were the first radio-links the team used as a proof-of-concept.

But Forrest noticed something: in the last couple of years, smartphone chips had gotten good enough to use in radios. Radio links, then, went from tens of thousands of dollars to hundreds of dollars instead–a 10-15 cost reduction. They were riding a curve.

“We basically built this giant WiFi network in Comuna 13,” Forrest explained.

Similarly, while vendors like Cisco and Juniper charged $20,000 for switches that “generally cost under $1,000 to make,” Forrest had noticed that data centers were building hardware on open standards using generic chips in a practice known as “whitebox networking.” He applied the same concept to last mile networks, saving tens of thousands of dollars, avoiding vendor lock-in, future-proofing the network, and jumping on another curve.

“The technology was fantastic,” Nico at Kaszek told me of the network at the time he met Forrest, “but there were question marks. We led the Seed anyway because we thought, ‘This is the type of founder we want to back; he will figure it out.’”

Figure it out he would have to, because the second advantage Forrest had was that he didn’t know what the fuck he was doing.

To wit: Forrest and Somos’ early band of pirates would put radio links on the roofs of buildings to catch the internet and light up a building. When a customer in one of those buildings subscribed, they would go to the building, hop on the roof, add a new ethernet cable, rappel down the side of the building, and drill a hole through the wall of the new subscriber’s apartment through which to run the cable and connect to the router.