Author: Kalle Rosenbaum & Linnéa Rosenbaum

This chapter explores Bitcoin's supply limit (21 million BTC)—or rather, its actual supply. We introduce how this limit is enforced and how you can verify that the current situation does not violate this rule. Furthermore, we examine the crystal ball to see what factors emerge when block rewards shift from being primarily driven by increased issuance subsidies to being primarily driven by transaction fees.

The well-known limited supply of 21 million BTC is considered a fundamental attribute of Bitcoin. But is this limitation truly insurmountable?

Let's first look at the current consensus rules regarding the supply of Bitcoin, and how much of it is actually usable. Pieter Wuille wrote a short article on Stack Exchange calculating the total number of Bitcoins after all of them have been mined:

If you add all the numbers together, you will get 20,999,999.9769 BTC.

— Pieter Wuille, Stack Exchange (2015)

However, due to numerous reasons—such as early issues related to Coinbase transactions causing miners to unintentionally claim less than the allotted amount; and the possibility of someone losing their private key—this supply cap will practically never be reached. Wuille concludes:

This leaves us with 20,999,817.31308491 BTC (taking into account everything from block 528333 onwards).

However, many wallets have been lost or stolen, some transactions have been sent to the wrong addresses, and some people have forgotten they ever owned Bitcoin. These numbers, if added together, could amount to millions. People are trying to tally all known losses here .

Therefore, we ultimately have: **???** BTC.

—— Pieter Wuille, Stack Exchange (2015)

Therefore, we can be certain that the maximum supply of Bitcoin is only 20,999,817.31308491 BTC. Any lost or unverifiable destroyed coins will decrease this number, but we don't know by how much. Interestingly, this isn't actually important, or rather, it's good for Bitcoin holders, as Satoshi Nakamoto stated :

The lost coin simply makes everyone else's coins slightly more valuable. You could think of it as a gift to everyone.

— Satoshi Nakamoto on the Lost Bitcoin, Bitcointalk forum (2010)

Limited supply will contract, and this should (at least in theory) lead to price deflation.

More important than the exact quantity in circulation is that this supply restriction is implemented without any central authority. As explained by someone nicknamed "chytrik" on Stack Exchange :

So the answer is, you don't need to trust that others won't increase the supply. You just need to run some code to verify for yourself that no one has exceeded the supply limit.

——chytrik, Stack Exchange (2021)

Even if some full nodes defect and decide to accept blocks with higher-value coinbase transactions, all remaining full nodes will simply ignore these blocks and continue on their original path. Some full nodes may (intentionally or unintentionally) run malware (see Section 9.2.2 for details); however, the entire collective will strongly protect the blockchain. The conclusion is that you can choose to trust the system without trusting any individual node.

4.1 Block Subsidies and Transaction Fees

The reward for a block (to the miner who mined it) consists of two parts: a "block subsidy" and "transaction fees." These block rewards need to cover Bitcoin's security costs. We can confidently say that, under current conditions, considering block subsidies, transaction fees, Bitcoin exchange rates, transaction pool size, hash power, and degree of decentralization, the incentive to ensure every player adheres to the rules is sufficient to protect a monetary system.

But what happens when the block subsidy approaches zero, meaning Bitcoin stops being issued? For simplicity, let's assume it's zero. At this point, the security costs of the entire system will be covered solely by transaction fees. What will happen when this occurs is unknown. The uncertainties are countless; we can only speculate. For example, Paul Sztorc's discussion on this topic on his blog "Truthcoin" is mostly speculative, but at least one thing is reliable (a reminder that Sztorc's "M2" is a measure of the fiat money supply):

Although the two rewards have been merged into a single "security budget," block subsidies and transaction fees are completely different. Their difference is like the difference between "VISA's total profit in 2017" and "the total M2 increase in 2017."

— Paul Sztorc, Long-Term Security Budget (2019)

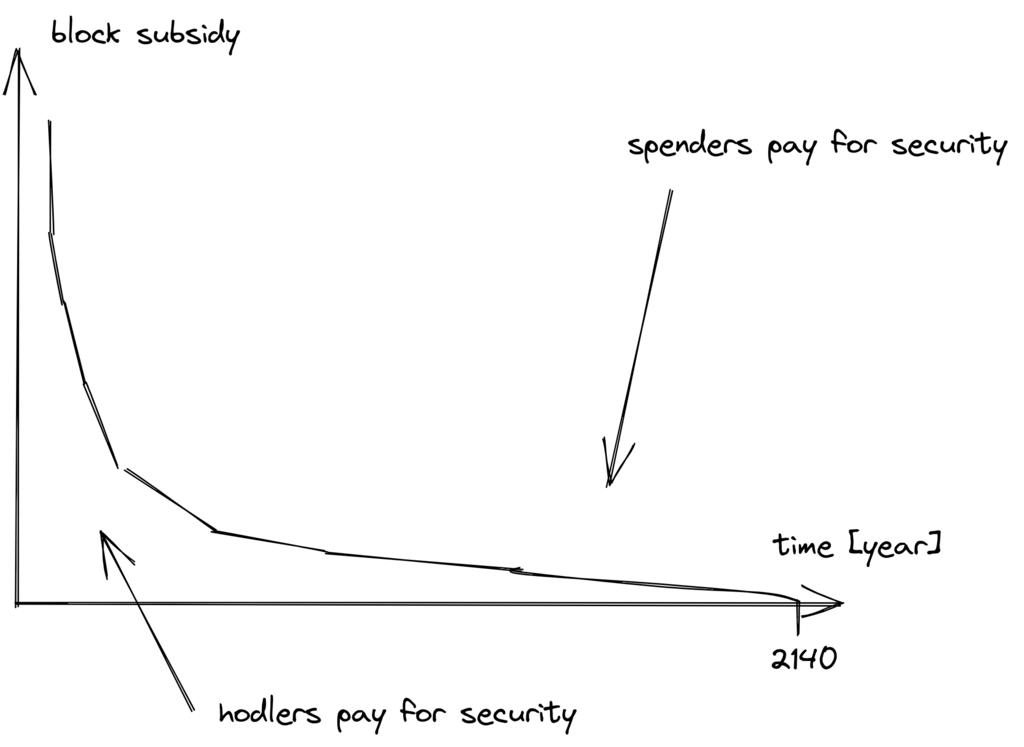

Currently, Bitcoin holders (through currency issuance) are paying for security. In the future, consumers will gradually assume this responsibility, as shown in the diagram below:

Figure 5. Over time, the burden of security costs will gradually shift from holders to consumers.

When transaction fees become the primary driver of mining, the entire incentive mechanism shifts. Most importantly, if miners cannot collect enough transaction fees from the transaction pool, rewriting Bitcoin's history may become more appealing than simply extending it. Bitcoin Optech has a dedicated chapter discussing this practice, known as " fee sniping ," written by David Harding.

"Fee sniping" is a problem that may arise as Bitcoin's block subsidies gradually disappear and transaction fees become the main component of block rewards. If transaction fees constitute the entire block reward, then a miner with

x% of the network's hash rate has anx% probability of mining the next block. Therefore, the expected reward for honest mining isx% of the transaction fees from the set of transactions with the highest fee rate in their transaction pool.However, miners can dishonestly attempt to mine again at a previous blockchain location and mine a new block to extend it (i.e., mine another chain). This behavior is called "fee sniping," and if all other miners are honest, the probability of this dishonest miner succeeding is

(x/(1-x))^2. While the probability of success for fee sniping is much lower than that of honest mining, attempting dishonest mining can be more attractive if previous blocks paid significantly higher fees (compared to transactions in the current transaction pool)—a small probability multiplied by a large number can be larger than a large probability multiplied by a small number.— David Hard, "Fee Sniper," Bitcoin Optech website

Frustratingly, if one miner starts fee sniping, it incentivizes other miners to do the same, reducing the number of honest miners. This could severely impact Bitcoin's overall security. Harding then outlines some countermeasures that can be taken, such as relying on transaction time locks to limit the starting point of a transaction on the blockchain.

Therefore, because the consensus on the limited supply remains unchanged, and BIP42 fixes a long-standing inflation loophole, block subsidies will decrease to zero around 2140. Will transaction fees be sufficient to protect the entire network by then? This is uncertain, but we do know a few things:

- A century is a very long time from Bitcoin's perspective. If Bitcoin has survived for such a long time, it has most likely changed significantly.

- If an overwhelming number of economic actors believe that the rules must be changed, such as by introducing perpetual annual inflation of 0.1% or 1%, then the supply of Bitcoin will no longer be limited.

- If block subsidies are gone and the transaction pool is almost empty, the system will become unstable due to fee-based penalties.

Because the transition to a system where only transaction fees serve as block rewards is too far off, it might be wise to refrain from drawing conclusions prematurely and instead address potential issues as much as possible now. For example, Peter Todd argues that Bitcoin's future security budget is insufficient, a real risk, and advocates for a small, perpetual inflation. However, he also believes that now may not be the right time to discuss this issue, as he stated on the "What Bitcoin Did" podcast :

However, this is a risk 10 or 20 years from now. That's a very long time. And who knows what the real risks will be then?

— Peter Todd on security budgets, What Bitcoin Did podcast (2019)

Perhaps we can think of Bitcoin as an organic entity. Imagine a small, slowly growing oak tree. But you never see a fully grown tree. So, wouldn't it be wiser to restrain our desire for control, rather than pre-setting all the rules for how this tree can grow?

4.2 Conclusion

Whether Bitcoin's supply will exceed 21 million BTC is something we can't say for sure today, and that (our inability to say for sure) might not be a bad thing. Ensuring a sufficiently high security budget is extremely important, but not urgent. We can continue discussing this for 10 to 50 years until we know more—if it's still a big deal then.