Author: Xiao Xiaopao

Original title: From the "140k poverty line" to the " middle-class cutoff line": To live or to live with dignity ?

I first encountered the "kill line" narrative in the X and Substack communities back in November. It originated from Mike Green's "140k poverty line" theory going viral in the US. It's quite interesting that this narrative spread and mutated into "kill line" in China just over a month later.

Unfortunately, my AI narrative radar (see here) wasn't ready yet at that time, otherwise I would have loved to see if the AI had grasped the narrative's spread and changes.

01

At the end of November, I read three articles by Mike Green on Substack:

These are three exceptionally long articles that will make you feel like you could read forever; the three articles combined could fill a small book.

I have tried my best to summarize it in Mandarin as follows:

The gist of the lyrics is: If you think the current economic data is good, but you are struggling to make ends meet, and you are still poor even with an annual salary of $100,000, it's not your fault. It's because the yardstick for measuring wealth is Doraemon's self-deception yardstick.

The article presents three viewpoints:

1. The "poverty line" is actually a misguided approach.

The official poverty line in the United States is an annual income of $31,200 (for a family of four); as long as your income exceeds $30,000, you are not considered poor.

But this ruler was made in 1963. The logic back then was simple: a family spent about a third of their money on food, so you only needed to calculate the minimum food cost and multiply it by 3 to get the poverty line.

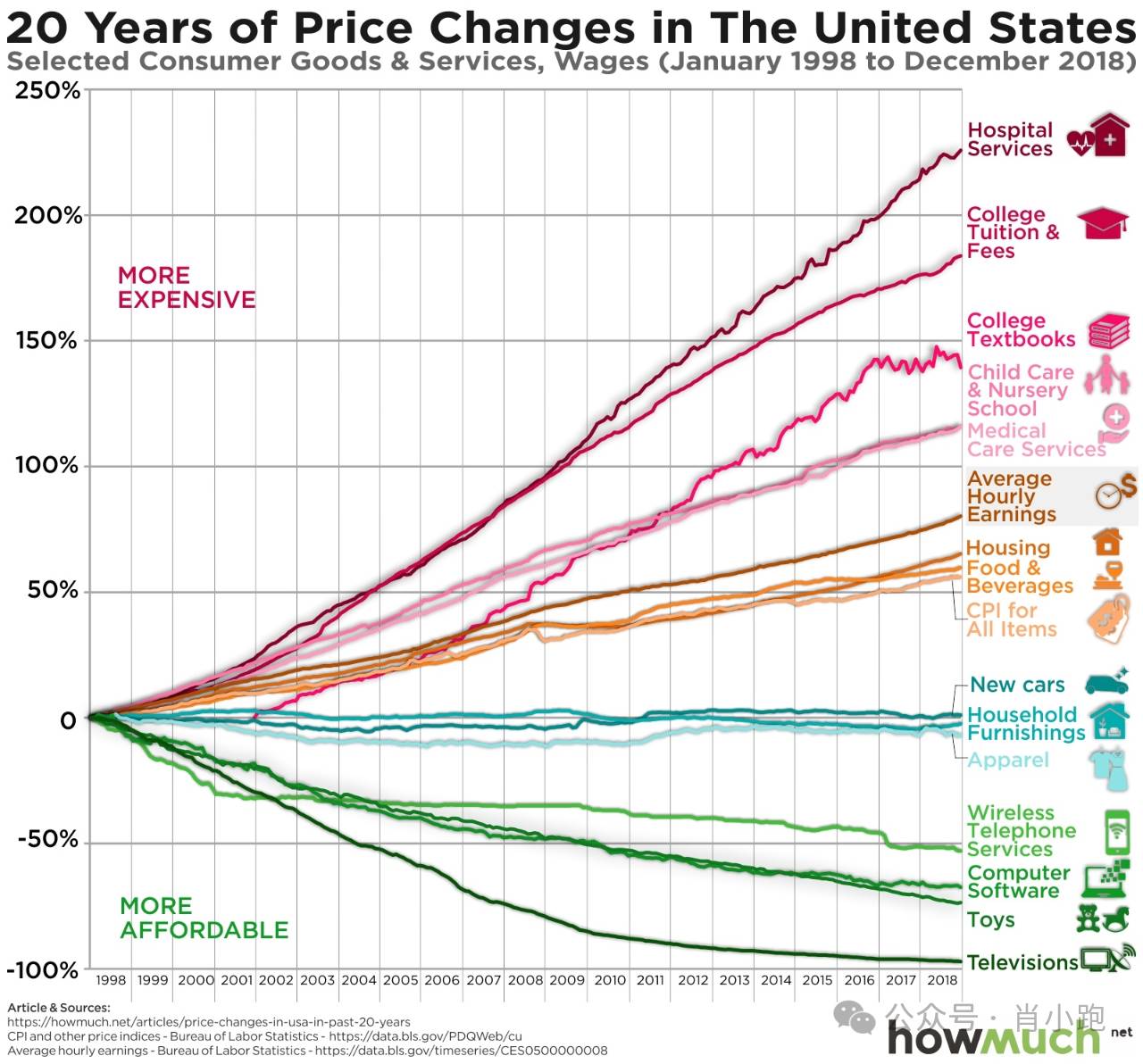

But the situation is very different now. Everyone has probably seen that famous diagram—"Baumol's Cost Disease":

Food is getting cheaper, but the costs of housing, healthcare, and childcare are skyrocketing. If you recalculate based on the living standards of 1963—that is, being able to "participate" normally in this society (having a place to live, a car to drive, someone to take care of your children, and access to medical care when you are sick)—the current real poverty line is not over $30,000, but $140,000 (about 1 million RMB), which is just enough to live decently in this society.

2. The harder you work, the poorer you become.

The US welfare system has a huge flaw: when you earn $40,000 a year, you are officially considered poor, and the government provides you with food stamps, covers your medical expenses (Medicaid), and subsidizes childcare. Life may be tough, but there's always a safety net.

But when you work hard and your annual salary rises to $60,000, $80,000, or even $100,000, disaster strikes: your income increases, but your benefits disappear. Now you have to pay for your expensive health insurance and rent in full on your own.

The result is that a family with an annual income of $100,000 may have less disposable cash left each month than a family with an annual income of $40,000 (receiving benefits).

This is the origin of the narratives on Chinese social networks about the "kill line" and "the kill line specifically targets the middle class": just like in a game, when your health drops to a certain threshold, you will be forcibly killed by a skill and taken down in one hit; the middle class, caught in the middle, happens to be at a point where welfare benefits are withdrawn, taxes are rising, and various rigid expenses (medical insurance, rent, childcare, and student loans) are all piling up. They have lost subsidies and are carrying high costs. Once they encounter unemployment, illness, or rent increases, they are locked in by the kill line.

3. The assets you own are actually quite worthless.

because:

Your house isn't an asset; it's prepaid rent. If your house's value increases from 200,000 to 800,000, are you richer? No. Because if you sell it, you still have to spend 800,000 to buy the same house. You haven't gained additional purchasing power; your cost of living has simply increased.

The legacy you're waiting for isn't a transfer of wealth: the baby boomer generation's legacy won't be passed on to you; it will be passed on to nursing homes and the healthcare system. Currently, elderly care in the US (dementia care, nursing homes) costs between $6,000 and over $10,000 per month. Your parents' $800,000 house will most likely end up as a series of medical bills, collected by medical institutions and insurance companies.

Your social class has become a caste: previously, hard work allowed you to climb the social ladder. Now, it's about "tickets"—Ivy League degrees, recommendations from inner circle members—and these "assets" are experiencing inflation rates higher than housing. So, a $150,000 annual salary might be enough to survive, but it won't buy you a ticket to the upper class for your children.

02

What exactly caused the "poverty line inflation" in the United States (or, in our context, the "major shift in the poverty line")?

Mike Green identifies three turning points in American history:

Turning point 1: The degeneration and monopolization of labor unions in the 1960s led to decreased efficiency and increased costs.

Turning point 2: The major shift in anti-monopoly in the 1970s, with large companies engaging in rampant mergers, controlling the market, and suppressing wages.

Turning point 3 (which everyone should be able to guess): The China shock. But the article's point is not that China forcibly took away jobs, but rather that American capitalists engaged in capital arbitrage—moving almost all of America's factories to profit from the trade difference.

But Professor Green didn't just kill without burying the dead. He finally proposed a very hardcore solution called "Rule of 65," the core idea of which is the "land reform" that we Chinese are very familiar with: (1) increase taxes on enterprises (but exempt investments); (2) large companies can no longer deduct money from their loans, resolutely cracking down on financial speculation; (3) reduce the burden on ordinary people: significantly reduce the income tax (FICA) of ordinary people, so that everyone has more cash on hand. Where will the missing money come from? Make the rich pay more, and open up the social security tax ceiling for the rich.

The Chinese experience is absolutely practical.

03

Mike Green's views have gone viral among the American middle class. However, they have sparked a collective backlash from the elite and various economists.

His article does indeed contain many data flaws. For example, he uses data from affluent areas (Essex County, the top 6% of affluent areas in the US in terms of home prices) as the national average; he assumes that all children attend expensive childcare centers (costing over $30,000 per year), when in reality most American families still raise their children themselves; and some concepts are somewhat confused, such as treating "average expenditure" as "minimum subsistence needs".

Later, Green appeared on many podcasts, where he tried to justify his actions by saying that the $140,000 did not refer to poverty in the traditional sense of "not having enough to eat," but rather to the "decent living threshold" for an ordinary family that could save some money without relying on government subsidies.

Although Mr. Green's math calculations seem to have been wrong, the critics didn't win either, because regardless of the actual poverty line, everyone's "feeling of poverty" is very real. And the sense of impending doom is becoming increasingly real—whether in the US or China.

Why? I think the real reason is "Bauer's disease".

The term "Baumer's cost disease" was coined by economist William Baumer in 1965 to describe an economic phenomenon:

Some industries (such as manufacturing) rely on machines and technology, which make them increasingly efficient and lower in unit costs; but some industries (such as education and healthcare) rely mainly on people, and it is difficult to significantly improve efficiency—a class still takes an hour, and a doctor needs time to see a patient, so it is impossible to speed up as much as a factory.

So here's the problem: wages across society rise along with those in highly efficient industries. To prevent teachers and doctors from leaving for higher-paying jobs, schools and hospitals also have to raise wages. But their efficiency hasn't improved much, yet wages have increased, resulting in ever-increasing costs and prices.

In other words, industries that can increase efficiency through machinery have raised wages overall, while industries that cannot increase efficiency also have to raise salaries to retain employees, but efficiency remains unchanged, so prices have increased. This is known as "Baumer's cost disease."

This explains why, in the image at the beginning of the article, the lines representing industrial products like televisions, mobile phones, and toys go downwards, indicating decreasing prices, while the lines representing education, healthcare, and childcare costs rise steadily.

The logic behind this is actually very realistic:

In any field that can be replaced by machines and automation, efficiency will only increase. Take mobile phones, for example. Although prices may not seem to have dropped much, their performance is vastly different from what it was a few years ago. Computing power and storage have increased several times over. This is essentially a "hidden price reduction" brought about by technology. Not to mention Chinese manufacturing: photovoltaics, EVs, and lithium batteries are becoming increasingly automated, driving costs down to rock bottom.

The problem lies in areas where "machines can't replace humans." When I was little, my nanny could look after four children by herself. Today, she can still look after a maximum of four, and in fact, because parents today have higher expectations, she can look after even fewer children. This means that the productivity of the service industry hasn't changed in decades, and may even have declined.

However, the service industry (specifically in the US) must raise wages to keep nannies and nurses in line with overall income levels, in order to prevent them from working as delivery drivers or in factories. The coffee beans in a coffee shop aren't expensive, but the exorbitant prices you pay mostly cover staff salaries, rent, and utilities. Efficiency hasn't increased, but wages have to, so these costs are inevitably passed on to consumers. (Note that this specifically refers to the US.)

So, the middle-class American families caught in the "cutoff line" aren't so poor they can't afford to eat. They have cars, iPhones, and various video streaming subscriptions, but their wallets are instantly emptied when faced with "service-related expenses" like buying a house, seeing a doctor, and raising children. Therefore, it's not that Americans have actually become poorer, but rather that their money is becoming increasingly difficult to spend in the face of those "inefficient but exorbitantly expensive" services.

At this point, I know everyone is wondering: Does China have a poverty line? Does China's poverty line affect the middle class? Has China's poverty line also increased?

The answer is most likely no.

Therefore, our "cut-off line" may not materialize. Dean Liu and I discussed this in the podcast episode " When China Becomes an Industrial Cthulhu, What's Left of Trade? Higher Productivity, Why Lower Wages? "

As we Chinese are all aware, Chinese society is more sensitive to service prices and is generally unwilling to pay for non-productive tools, especially services. In the expenditure structure of labor reproduction, certain service expenditures in China have long been suppressed to a very low level, to the point that "this part of the wage can be skipped." When services are undervalued and welfare levels differ, the wage system naturally exhibits a completely different structural form from that in the West.

This creates a strange phenomenon: no matter what, you can still "survive" because the cost of living can be kept extremely low.

Therefore, while China may not have a "cutoff line," it doesn't mean there isn't an implicit threshold. For example, how low can the dignity of service providers be suppressed? How high can the intensity be?

So, as the saying goes: everything comes at a price.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/BitpushNewsCN

BitPush Telegram Community Group: https://t.me/BitPushCommunity

Subscribe to Bitpush Telegram: https://t.me/bitpush