Co-spend Heuristic Fails, Badly, In Novel Out-Of-Sample Testing

The co-spend heuristic, the cornerstone of blockchain forensics, exhibits behavior in controlled experiments that raises serious concerns about its reliability. Specifically, it detects structure and signal where none exists and demonstrates an alarming lack of accuracy overall.

This has significant implications not only for blockchain forensics but for the broader digital asset legal and compliance ecosystem. This single heuristic underpins the industry’s largest forensics and compliance service companies and supports numerous legal cases worldwide. In what we believe to be the first out-of-sample test of the heuristic’s performance, the results indicate substantial limitations.

It is already concerning that a technique first published in 2013, and used widely by law enforcement ever since, should have its accuracy publiclyu tested only in 2025 and on a very small sample dataset.

It is noteworthy that a technique first published in 2013 and used widely by law enforcement over the following years should have its first public accuracy test published in 2025, and on a relatively small dataset. Furthermore, comparing our out-of-sample results with prior in-sample work reveals indicators consistent with overfitting. This suggests that testing methodologies may require improvement across the industry, as users and service providers may not be adequately validating their tools or may be obtaining substantially different results.

These are substantial claims. Here is our plan to support them:

- Explain, briefly, in-sample vs out-of-sample testing

- Present a simple scheme we developed to build out-of-sample test data

- Summarize our test results vs prior in-sample results

- Comment on implications

A detailed paper with all the data is available here.

This work builds on our previous work showing that Coinjoins have been endemic on Bitcoin since 2009, which led us to submit an Amicus Brief arguing that the co-spend heuristic required more rigorous testing before being presented in court as a forensic method with minimal false positives, as occurred in US v Sterlingov.

We subsequently developed the technique to convert ZK Mixer transactions into Coinjoin transactions, enabling this study.

We view this as a scientific exercise in evaluating a classification heuristic, similar to other model testing. What we did not anticipate was finding such pronounced differences in out-of-sample performance.

Our initial hypothesis was that the reliability of the heuristic would support law enforcement requests for information to intermediary businesses like exchanges, and that results would be adequate for search warrant requests and similar “probable cause” legal processes.

We had also expected to find a reliability level that would require corroborating evidence for more demanding legal standards. However, we were surprised to find error rates that, appear to be no more than uneducated guesses that should not be used to support much of any law enforcement activity at all.

This is a single study and we do not claim these performance characteristics generalize to all cases or necessarily to the most important cases.

One study employing a particular approach to out-of-sample testing does not render a technique meritless. However, it does demonstrate the need for more rigorous testing and reconsideration of how the legal system evaluates blockchain analytics.

Even setting aside our specific findings, it is problematic that comprehensive testing of this nature is first appearing more than a decade after law enforcement began using them.

In-Sample vs Out-of-Sample Testing

When developing a model for any task, one must start with data. For a classification model — one that applies labels to input data points — this data must include a set of input points with independently and objectively ascertainable labels.

Imagine building a model that takes portrait photographs as input and outputs the subject’s hair color. To train and evaluate your model, you would need a process to label the hair color for each photograph. You would require “gold standard” data with 100% accurate labeling.

If you train your model on 100 photographs and then test performance on those same 100 photographs, this is called “in-sample” testing.

If you take that same model and test it on 100 different photographs — photographs never seen before where someone has correctly labeled the hair color — that is “out-of-sample” testing.

Generally, we expect out-of-sample performance to be worse than in-sample performance. An engineer comparing two models with access to a total of 200 labeled photographs will typically:

- Train each model on 100 randomly selected photographs

- Measure performance on the other 100 photographs

- Repeat this 100 times

- Compare the average out-of-sample performance of the two models

The concern underlying this process is that excessive training and testing on the same data may lead to “overfitting.”

The model might pick up on unintended features like the subject’s shirt color, eye color, race, or other characteristics present in the data.

Importantly, this type of overfitting and resulting model bias does not require any bias or conscious effort by the engineers.

If every blonde in your dataset has blue eyes, you cannot determine whether the model learned to detect blonde hair or blue eyes.

If every blonde is male, has a mustache, or has some other distinguishing characteristic, the model may be biased without the engineers making any errors.

Similarly, if a company has only 200 photographs and spends years building models, none of the testing is properly “out-of-sample.” Engineers make decisions based on performance measured through the above process, which continues to rely on the same 200 photographs.

Now scale this to 200,000 photographs, hundreds of engineers, and a decade of model building. It becomes plausible that all tooling depends on features in the dataset that no human can detect but the computer consistently identifies.

For photographs, this is manageable because the supply of labeled photographs is practically infinite.

The same is mostly true for DNA samples, fingerprints, and many other forensic subjects because you can always acquire more data. For radar guns measuring speed, you can easily stage fresh experiments. Test data abounds for these cases.

But what if your model studies an extremely rare disease, Panda mating, solar eclipses, or extreme weather?

Acquiring additional data in such circumstances is not straightforward.

The earliest tests of General Relativity required waiting for specific types of eclipses. Physicists then spent decades designing better, more reliable, and more repeatable tests of the theory. Clever test design is a core component of science.

The co-spend heuristic is often used to analyze illicit blockchain services where labels are only available after the government has made arrests, or seized software code, servers, or logs. This creates a limited dataset where years of work may be conducted with the same small set of samples, making any analysis effectively in-sample testing.

This is fundamentally different from DNA testing, where a technique used to convict criminals can be tested out-of-sample using blood samples from any source.

Our work here attempts to design more robust out-of-sample tests for this challenging case. We acknowledge our approach is not perfect and involves compromises and drawbacks.

However, the alternative is limiting study to services captured by law enforcement in a fundamentally unscientific exercise.

How can one determine if tools work for criminals still on the run — those law enforcement is actively pursuing— if testing cannot occur until after apprehension?

The Coinjoin — ZK Mixer Isomorphism

Our work is built around a method to convert ZK Mixer data on Ethereum into Bitcoin-like Coinjoin obfuscation. This is detailed in a paper we recently published providing careful definitions and algorithms showing exactly how to convert between ZK Mixers and Coinjoins. For exact details, please refer to that paper. Here we sketch the process sufficiently to build intuition.

A Coinjoin has multiple inputs and multiple outputs. Assume for now that total input equals total output. We can convert this into a sequence of mixer transactions by feeding all inputs to a single commingled address and then disbursing all outputs from that address. This is how a mixer operates.

With real mixers, we do not expect a “fill and drain” pattern where the balance is zero, then large, then returns to zero. Instead, we expect a resting balance inside the mixer far exceeding any individual transaction.

This can be achieved by stringing these operations together in an interleaved fashion.

If the first Coinjoin only withdraws 10% of the balance, feed the remaining 90% into the next “Coinjoin” and repeat. Chaining Coinjoins this way, where individual deposits and withdrawals are smaller than balances pushed between rounds, is how Coinjoin-based mixing services operate.

The reverse mapping should now be apparent.

Break all ZK Mixer transactions into groups consisting of consecutive transactions on the same side. Are there 7 consecutive deposits with no withdrawals? That forms a batch of 7.

Four consecutive withdrawals without a deposit? Another batch.

Then build Coinjoins from consecutive pairs of these batches while carrying the resting balance forward.

That is the entire procedure.

The process is straightforward. Coinjoins work by simultaneously transferring funds between two separate, large groups, such that all outputs are collectively sourced from all inputs. Chaining this several times means all outputs derive from such a large and disparate set of inputs that individual responsibility cannot be readily assigned. This effectively commingles funds while the Coinjoin executes.

ZK Mixers make this explicit by commingling funds in a common account.

Running this type of service manually is relatively simple.

The technical complexity addresses ensuring some combination of:

- records are destroyed quickly enough that no government can recover them;

- sufficient anonymity prevents attribution of service operation; and

- existing records are insufficient to attach inputs to outputs.

The idea behind ZK Mixers is that public records alone are insufficient for reliable tracing and no operator with privileged information exists. This requires technical sophistication. However, note two things.

First, sufficient information to deanonymize the service does exist. The system is “ZK” in that public information contains proofs of ownership revealing nothing about the incoming deposit. But if you know which computer generated those proofs and their location before submission for withdrawal, deanonymization is possible. The proofs are zero-knowledge, but the information exists in the universe.

Second, a central operator in a secure location works equally well if nobody can access or compel disclosure of the records. The public records are what we measure, not all information in the “system” as a whole.

Tracing is a reconstruction exercise from public information. Under this framework, these techniques provide equivalent obfuscation.

Test Results

As discussed above, we generally expect out-of-sample performance to be worse than in-sample performance.

However, we also care about how the out-of-sample performance differs from in-sample performance.

If we observe the model never makes a certain type of error in-sample but makes that error frequently out-of-sample, we have cause to suspect overfitting.

For example, if a model never misses blonde hair in-sample but performs no better than random guessing out-of-sample, we might examine eye color, gender, facial hair, outfit, race, or other possible biases in the training data. The behavior itself provides an excellent clue that something is problematic, even if the error rate does not identify what is wrong.

What we find with the co-spend heuristic is not just worse performance out-of-sample, but substantially worse performance. Furthermore, we find that a certain type of error — a “false positive” where the heuristic incorrectly classifies an address as inside a cluster — is nearly absent in-sample but appears at rates sometimes exceeding 50% out-of-sample.

At minimum, these results indicate that significantly more testing of this heuristic is required. Our results also demonstrate that under certain conditions, this heuristic exhibits substantial limitations.

In-Sample

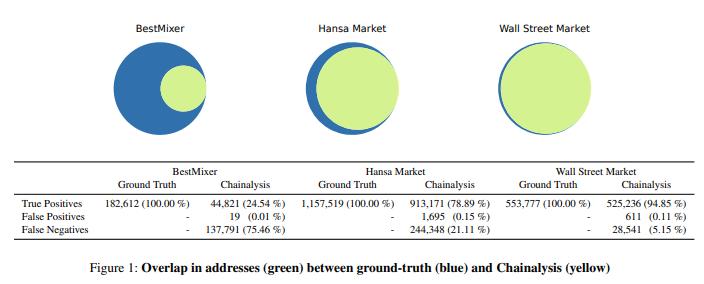

Chainalysis, the oldest and largest provider of tools built on the co-spend heuristic, has referenced a single study examining three captured illicit services and measuring the “false positive rate” (FPR) and “false negative rate” (FNR) for each service. “False positive” is defined above, and “false negative” refers to cases where an address that should be included in a cluster is excluded from that cluster.

That study — which has been touted as proof of accuracy— reports the following results:

The FPR is nearly zero in all cases while the FNR varies: 5%, 21%, or 75%. This already suggests a potential overfitting problem because the heuristic makes one type of error frequently and another type rarely.

One would expect a well-functioning tool to fail with somewhat similar frequency in both directions — not necessarily 1:1, but certainly not 7,250:1 as with BestMixer.

It is particularly noteworthy that one error rate approaches zero while the other reaches 75%. This pattern suggests the engineers may have been optimizing primarily for FPR minimization.

Before concluding “a low FPR is acceptable,” recognize that tuning the model for near-zero FPR might inadvertently cause overfitting or other issues manifesting as different performance on different data.

Driving FPR to zero on a blonde-hair detector might lead to a model that relies on eye color, race, or other factors. As with all modeling, the defense against this problem is testing against previously unseen data and reconsidering assumptions.

Out-of-Sample

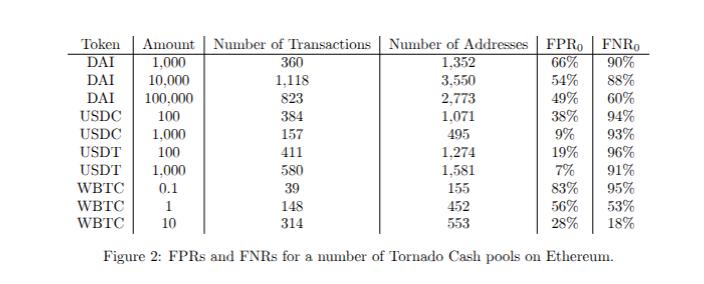

To obtain out-of-sample data, we examined 10 Tornado Cash instances on Ethereum covering 4 different ERC-20 tokens. Full details of our selection criteria and heuristic application are provided in the paper. Here are the FPR and FNR from our tests:

We find FPRs between 7% and 83% and FNRs between 18% and 96%. As expected, these are worse than the in-sample results. They also indicate significant performance limitations.

For one mixer (the smallest we examined), we found FPR 83% and FNR 95%. These results are abysmal, and a tool exhibiting such performance characteristics is not only ill-suited for forensic application, it is no better than poor guesswork.

It gets worse.

Our procedure generates Bitcoin-like transactions where there is a single large cluster — Tornado Cash — and every other address is a cluster of 1. We can verify this because we can read the Tornado Cash code and we wrote the translation software. In every case, the largest cluster should be the mixer and, ideally, should contain only mixer addresses. Ideally, no other cluster should contain mixer addresses.

Here are cluster sizes in blue and service-address-in-cluster counts in red for the 100 largest identified clusters from the 10,000 DAI Tornado Cash instance:

It is immediately apparent that:

- Most service addresses are in the largest clusters

- Those clusters often contain many non-service addresses

- There is a long tail of small address clusters which are not signle addresses

- Service addresses are distributed throughout many of those clusters

This is not a complete failure in that the heuristic is at least detecting something related to a service. However, the heuristic is mixing service addresses with non-service addresses, and it identifies multiple services where it should find only one.

The software is also identifying patterns associated with the service, albeit imperfectly. This suggests the heuristic may function adequately in some contexts but is limted in its general applicability.

We are certainly not claiming this heuristic produces random results as there is observable structure related to the correct answer. But it is only useful insofar as detecting the largest cluster where half the contained addresses are part of the service is more helpfu than simply guessing.

Remember, a 50% FPR is not the same as coin flip for this task because there are a lot more than 2 possible outcomes. However, it represents concerning performance for a forensic tool intended for court use and admissible as evidence.

The paper provides these results for all 10 mixers. For all DAI mixers we examined, here is the fraction of each identified cluster that consists of Tornado Cash addresses:

Each color represents a different mixer, with the 100 largest clusters presented from left to right. These details are secondary to the main finding. An ideal result would be a single 100% value on the left for each color and then all zeros.

Instead, we observe a distribution of rates mostly between 20% and 80% across 100 clusters per mixer. The heuristic does not meet expected performance standards in these tests.

In the paper we write down precisely what we mean by success and then present data which makes clear that none of the examined examples comes close to that definition.

Comparison

Finding near-zero FPRs alongside substantially larger FNRs in-sample suggests overfitting. Our out-of-sample analysis demonstrates the low FPR does not generalize to at least some novel datasets. This provides statistical evidence consistent with overfitting.

To make this clear let us return to the hair color detection analogy.

An engineer provides a black box claiming it to be able to identify blonde hair in photos. Their research shows that when it indicates “blonde hair present,” blonde hair is indeed present 99.9% of the time.

However, when that same black box is used with photos of blondes selected from the engineer’s own examples, it often fails to correctly identify the hair color. When it says “blonde,” it is always correct. But when you provide a blonde, it is frequently incorrect, at whcih point you may already suspect something is wrong with the tool.

Then you test it on your own photographs and find it is frequently incorrect in both directions — approximately half the time.

What conclusions might you draw about the black box? Perhaps you are using it incorrectly.

Perhaps the engineer was mistaken.

Perhaps the engineer lacks adequate expertise.

Or perhaps your photos differ substantially from whatever the engineer trained on.

Numerous explanations are possible.

The important conclusion is that none of these explanations suggest the black box is fit for its intended purpose.

Discussion

We developed a novel method for testing the co-spend heuristic that synthesizes Bitcoin-like transaction sets where cospend transactions are possible from ZK Mixer data on Ethereum. We acknowledge this is not the ideal out-of-sample test for the heuristic. The ideal test would require perfectly-tagged data for an actual illicit service on Bitcoin that is not yet publicly known. The only way to achieve this would be to operate such a service and publish the test before law enforcement intervention and seizure of software code, logs, and servers.

Would such a test be superior?

Such a test would not require our isomorphism, would have fewer steps, and would more closely replicate the real-world experience of using the co-spend heuristic to investigate a novel mixer.

However, it would require the testing team to operate an illicit service, acknowledge this publicly, and publish data facilitating their arrest.

While someone could theoretically publish such work anonymously, this requires simultaneously admitting to crimes carrying lengthy prison sentences, publishing evidence sufficient for conviction, and challenging law enforcement methods.

Our method addresses only the third element, which is already somewhat challenging in practice.

If the only acceptable test requires testers to admit criminal activity and publish proof of guilt, then rigorous testing becomes impractical. Rejecting our premise without proposing an alternative testing methodology is not constructive. Our approach is conducted in good faith, is reasonable, and produces meaningful results.

Is it perfect? No.

Do we expect immediate abandonment of the co-spend heuristic? Of course not.

We neither want nor believe that is the appropriate outcome.

However, our results suggest the reliability of various blockchain forensic techniques may have been overstated for some time.

Much of the blockchain advocacy and compliance industry is built around claims that additional analytics can solve web3’s compliance challenges. It is difficult to take such claims seriously when the underlying tools have received limited rigorous, critical, or scientific testing.

Testing tools helps toolmakers improve. Assuming tools work without proper scientific testing typically ends poorly. These have not been controversial claims since before the Enlightenment.

Nobody double-blind tests parachutes because:

- The methodology would be challenging;

- If possible, subjects would likely die;

- Convincing non-blind tests are feasible; and

- Parachutes are obviously superior to no parachute.

The co-spend heuristic does not fit that mold.

Proper testing is necessary, particularly when false positives might lead to wrongful imprisonment, inverting the parachute testing concern from “testing might kill people” to “failure to test might imprison innocent people.”

What we present is a creative, rigorous, and importantly scientific study demonstrating that the co-spend heuristic exhibits substantial limitations under conditions not entirely dissimilar to its most common and highest-profile use case: investigating novel illicit blockchain-based services.

This study demonstrates there are reasonable conditions under which the heuristic does not perform adequately. This, by itself, is sufficient to raise questions about the conditions under which the heuristic should and should not be used, admitted in court, relied upon for search warrants, or employed in various other common applications of the co-spend heuristic and tools built upon it.

We hope this initiates a period of constructive discussion about the reliability of many techniques. We hope it sets the field on a course toward more rigorous standards and, most importantly, standard-setting processes consistent with the rest of forensics.

Co-spend Heuristic Hallucinations was originally published in ChainArgos on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.