Written by: Ada | TechFlow TechFlow

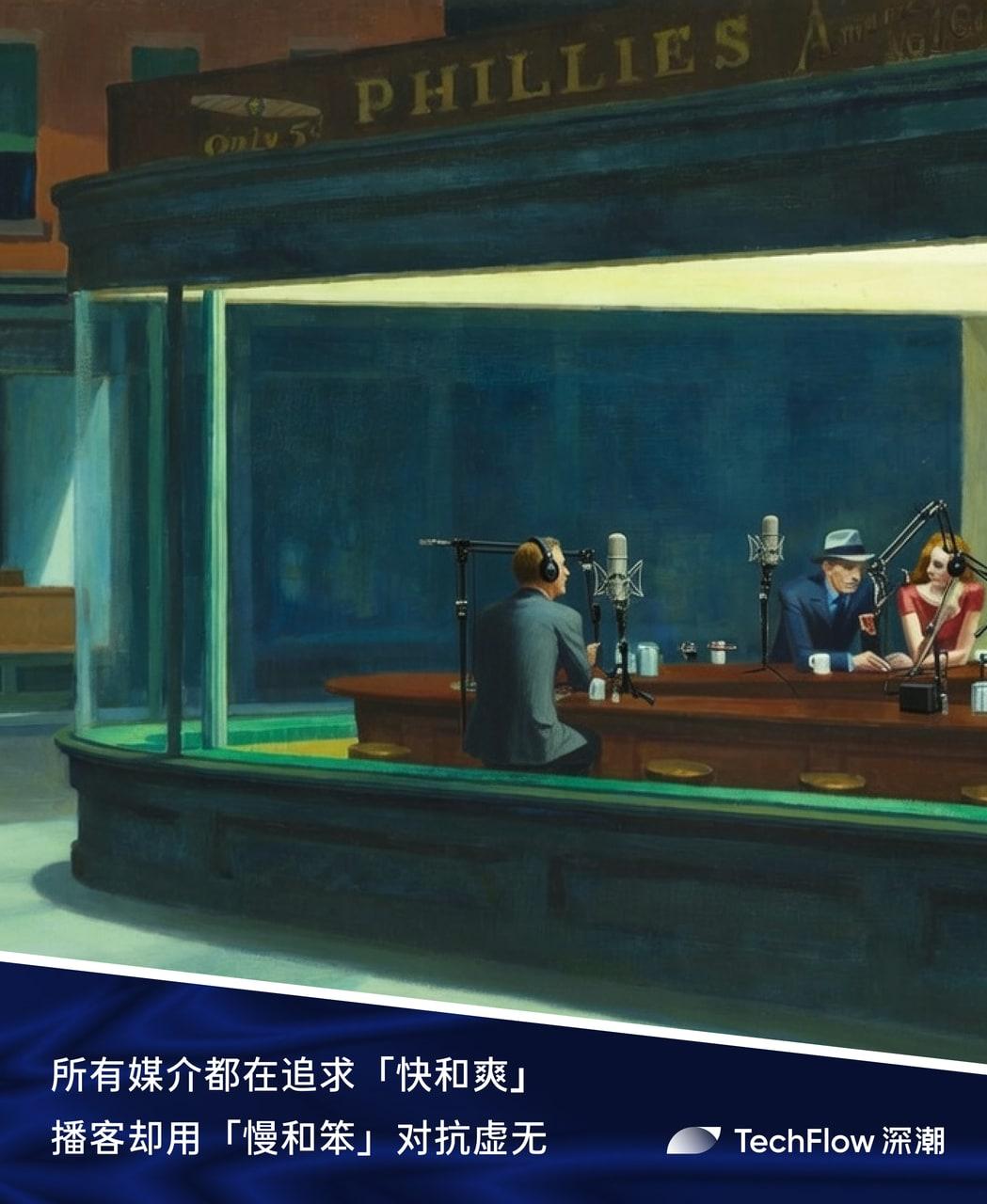

But strangely enough, more and more people in the crypto industry are making podcasts.

The cost of not taking money

“I’ve refused to accept money from many people who have offered it to me,” Mable said.

"But why did you persist for so long?" we asked.

“Because I still want to talk,” she said without hesitation.

"Aren't you worried that it will affect your subsequent communication with the guests?" we pressed.

The Paradox and Dilemma of Commercialization

Not all podcast hosts are as averse to commercialization as Mable.

Essentially, this is a very niche market.

This gap is not just about money, but also about the difference in the structure of influence.

Those gains that cannot be measured in money

Sea, however, understands this from another perspective.

To put it more simply, the process of making a podcast is inherently enjoyable.

Methodology of Success

“Many people just record the chat,” Liu Feng said, “but that’s not the same as a program.”

But there is an even more hidden dilemma.

How can I persevere?

Vivienne remembers it clearly; it was when Cryptoria had just reached its 15th issue.

end

This is a real-world question, and the answer lies in the meaning of podcasts.

The hosts of Chinese encrypted podcasts may not realize how important the things they are doing are.

On the ruins of traffic, they are rebuilding a stronghold for in-depth content.

While blockchain records wealth, podcasts record vibrant souls.

WeChat Official Account: TechFlow TechFlow

Subscribe to our channel: https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

Telegram: https://t.me/TechFlowPost

Twitter: @TechFlowPost

Add the assistant's WeChat ID to join the WeChat group: blocktheworld

Donate to TechFlow TechFlow and receive blessings and a permanent record.

ETH: 0x0E58bB9795a9D0F065e3a8Cc2aed2A63D6977d8A

BSC: 0x0E58bB9795a9D0F065e3a8Cc2aed2A63D6977d8A