Written by: milian

Compiled by: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

In the world of cryptocurrency, the promise of "crypto cards that do not require KYC (Know Your Customer) verification" occupies a peculiar position.

It was touted as a technological achievement, packaged as a consumer product, and aspired to be an "escape route" from financial surveillance. Cryptocurrency could be used to make purchases wherever Visa or Mastercard was accepted, without requiring identity verification, personal information, or any questions.

You might naturally ask: Why hasn't anyone succeeded in doing this yet? The answer is: Actually, it has been done—more than once—but it has also failed time and time again.

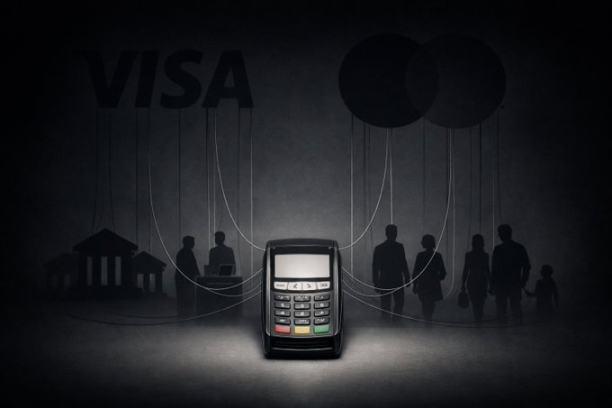

To understand why, we can't start with cryptocurrencies themselves, but rather with the infrastructure of crypto cards. Debit and credit cards are not neutral tools; they are "licenses" granted by a strictly regulated payment system dominated by the two giants, Visa and Mastercard. Any card that can be used globally must be issued by a licensed bank, routed via a recognizable six-digit BIN code, and subject to a series of explicit compliance contractual obligations—including a strict prohibition on anonymous end-users.

There are no technical "workarounds" for building cards on top of the Visa/Mastercard system. The only way is through "false statements."

The "KYC-free cryptocurrency cards" commonly sold on the market are essentially corporate cards. Aside from prepaid cards with extremely low limits designed for large-scale use, these cards are legally issued to businesses (usually shell companies) for the purpose of internal employee expense reimbursement. In some cases, these businesses are legitimate; in others, their existence is solely for obtaining the necessary qualifications to issue the cards.

Consumers are never the intended cardholders of these cards.

This structure might work in the short term. Cards are distributed, labeled as consumer products, and allowed to exist tacitly until they attract sufficient attention, but attention will always draw scrutiny. A Visa compliance representative can trace the issuing bank through the BIN code, identify abuse, and then terminate the entire program. Once this happens, accounts are frozen, the issuer is cut off, and the product disappears—the whole process typically takes six to twelve months.

This model is not hypothetical. It is a repeatable, observable, and well-known reality within the payments industry.

This illusion persists only because "shutting down" always comes after "going online."

Why are users attracted to "KYC-free cards"?

The appeal of KYC-free cards is very specific.

It reflects the real-world limitations faced in accessing funds, intertwining privacy and availability issues. Some users prioritize privacy out of principle, while others live in regions where formal banking services are limited, unreliable, or outright deprived. For users in sanctioned countries, KYC is not only a privacy violation but also a direct exclusion, severely restricting when and which financial channels they can use.

In these situations, non-KYC payment tools are not an ideological choice, but a temporary "lifeline".

This distinction is crucial. Risk doesn't disappear just because it's "necessary"; it only becomes concentrated. Users who rely on these tools are often fully aware that they are making trade-offs: sacrificing long-term security for short-term usability.

In practice, payment channels that lack identity verification and transaction reversibility will inevitably accumulate transaction flows that fail to pass standard compliance reviews. This is an operational reality observed by issuers, project operators, and card networks, not theoretical speculation. When access is unimpeded but tracking capabilities are weak, funds blocked elsewhere will naturally flow here.

Once transaction volume increases, this imbalance will quickly become apparent. The resulting concentration of high-risk funds is the main reason why these projects, regardless of their marketing or target users, will ultimately attract scrutiny and intervention.

Marketing claims surrounding KYC-free cryptocurrency cards are consistently exaggerated, far exceeding the legal constraints faced by payment network operators. This gap between "promise" and "responsibility" is rarely noticed during user registration, but it foreshadows the eventual fate of these products as they scale up.

The harsh reality of payment infrastructure

Visa and Mastercard are not neutral intermediaries. They are regulated payment networks that operate through licensed issuing banks, acquiring banks, and contract compliance frameworks that require end-user traceability.

Every globally usable card is linked to an issuing bank, and each issuing bank is bound by network rules. These rules require that the end user of the card must be identifiable. There are no opt-out mechanisms, no hidden configurations, and no technical abstractions that can circumvent this requirement.

If a card can be used globally, then by definition, it is embedded in the system. The constraints are not at the application layer, but in the contracts governing settlement, issuance, liability, and dispute resolution.

Therefore, achieving unlimited, KYC-free spending through Visa or Mastercard is not just difficult—it's impossible. Anything that seems to contradict this reality either operates within strict prepaid limits, misclassifies the end user, or is simply "delaying" rather than "avoiding" enforcement.

Detection was effortless. A single test transaction was enough to expose the BIN code, issuing bank, card type, and project administrator. Closing the project was an administrative decision, not a technical challenge.

The fundamental rule is very simple:

If you haven't done KYC for your card, then someone else has.

Only the person who completed KYC procedures truly owns the account.

Detailed Explanation of "Company Card Vulnerability"

Most so-called KYC-free cryptocurrency cards rely on the same mechanism: corporate expense cards.

This structure is not mysterious. It's a well-known "loophole" in the industry, or rather, an "open secret" fostered by how corporate cards are issued and managed. A company registers through a Know Your Business (KYB) process, which is typically less stringent than for individual consumers. From the issuer's perspective, the company is the customer. Once approved, the company can issue cards to employees or authorized consumers without additional identity verification at the cardholder level.

In theory, this is intended to support legitimate business operations. In practice, however, it is often abused.

End users are treated as "employees" on paper, not as bank customers. Because of this, they are not subject to separate KYC verification. This is the secret behind these products' ability to claim "KYC-free."

Unlike prepaid cards, corporate prepaid cards can hold and transfer large sums of money. They were not designed for anonymous distribution to consumers, nor were they intended for the escrow of third-party funds.

Cryptocurrencies typically cannot be deposited directly, thus requiring various back-end "workarounds": wallet intermediaries, conversion layers, internal ledgers, etc.

This structure is inherently fragile. It can only last until it attracts sufficient attention, and once attention is drawn, enforcement becomes inevitable. History shows that projects constructed in this way rarely survive more than six to twelve months.

The typical process is as follows:

- Create a company and complete KYB verification with the card issuer.

- From the issuer's perspective, this company is the customer.

- The company issues cards to "employees" or "authorized users".

- The end users were treated as employees, not bank customers.

- Therefore, the end user does not need to undergo KYC.

Is this a loophole, or a violation of the law?

Issuing company cards to actual employees for legitimate business expenses is legal. However, publicly distributing them as consumer products to the general public is not.

Issuers face risks once cards are distributed to "fake employees," used for public marketing, or primarily for personal consumption. Visa and Mastercard do not need new regulations to take action; they only need to enforce existing rules.

One compliance review is sufficient.

Visa compliance personnel can register themselves, receive the card, identify the issuing bank via the six-digit BIN code, trace the entire project, and then close it.

When something happens, the account will be frozen first. An explanation may come later, or sometimes there may be no explanation at all.

Predictable life cycle

The failures of cryptocurrency card projects marketed as "KYC-free" are not random, but follow a strikingly consistent trajectory, repeating themselves in dozens of projects.

The first stage is the "honeypot phase." The project launches quietly, early access is limited, spending is as advertised, and the first batch of users report success. Confidence begins to build, and marketing accelerates. Credit limits are increased, and influencers heavily promote the promises. Success screenshots circulate widely, and the previously niche project becomes highly visible.

Visibility is the turning point.

Once transaction volume increases and a project attracts attention, scrutiny becomes inevitable. Issuing banks, project managers, or card networks will review its activities. BIN codes are identified. The significant discrepancy between the card's marketing claims and its contractually permitted operations becomes apparent. At this point, enforcement is no longer a technical issue, but an administrative one.

Within six to twelve months, the outcome is almost always the same: the issuer is warned or the partnership is terminated; the project is suspended; the card stops working without warning; the balance is frozen; and the operator disappears behind customer service tickets and generic email addresses. Users have nowhere to appeal, no legal standing, and no clear timeline for the recovery of their funds—if they can even recover them.

This is not speculation, nor is it theory. It is an observable pattern that recurs across different jurisdictions, issuers, and market cycles.

KYC-free cards operating on the Visa or Mastercard track will always be shut down; the only variable is time.

The Inevitable Cycle of Destruction (Summary)

- Honeypot stage: A "KYC-free" card quietly launched. Early users succeeded, influencers promoted it, and transaction volume increased.

- Regulatory squeeze period: Issuing banks or card networks review projects, mark BIN codes, and identify abuses of issuance structures.

- intersection:

- Forced to introduce KYC → Privacy promises completely collapse.

- Project owner absconds or disappears → Card deactivated, balance frozen, support channels become invalid.

There is no fourth ending.

How to identify a "KYC-free" cryptocurrency card in 30 seconds

Take, for example, the marketing images for Offgrid.cash's so-called non-KYC cryptocurrency card. Zooming in on the card immediately reveals a detail: the "Visa Business Platinum" logo.

This isn't a design embellishment or brand choice; it's a legal classification. Visa does not issue business platinum cards to anonymous consumers. This label means it participates in a corporate card program, and the ownership of the account and funds belongs to the company, not the individual user.

The deeper implications of this structure are rarely explicitly stated. When users deposit cryptocurrency into such systems, a subtle but crucial legal shift occurs: the funds are no longer the user's property, but rather become assets controlled by a corporation holding the corporate account. Users have no direct relationship with the issuing bank, no deposit insurance, and no right to file complaints with Visa or Mastercard.

Legally speaking, users are not customers at all. If the operator disappears or the project is terminated, the funds are not "stolen," but rather you voluntarily transferred them to a third party that no longer exists or can no longer access the card network.

When you deposit cryptocurrency, a key legal shift occurs:

- The funds no longer belong to you.

- They belong to the company that completed the KYB verification with the issuing bank.

- You have no direct relationship with the bank.

- You have no deposit protection.

- You have no right to complain to Visa or Mastercard.

- You are not a customer. You are just a "cost center".

- If Offgrid disappears tomorrow, your funds are not "stolen"—you have legally transferred them to a third party.

This is a core risk that most users are unaware of.

Three immediate warning signs

You don't need insider information to determine if you're funding a corporate credit card. Just look at three things:

- The card type printed on the card: If it says Visa Business, Business Platinum, Corporate, or Commercial, then it's not a consumer card. You are being registered as an "employee".

- Network logo: If it is backed by Visa or Mastercard, it must comply with anti-money laundering, sanctions screening, and end-user traceability regulations.

- There are no exceptions.

- There is no technical flexibility.

- It's only a matter of time.

- Unreasonable spending limits: If a card offers the following simultaneously: high monthly credit limit, top-up capability, global usability, and no KYC required, then someone else must have done the KYB on your behalf.

Currently, this type of card project is being marketed.

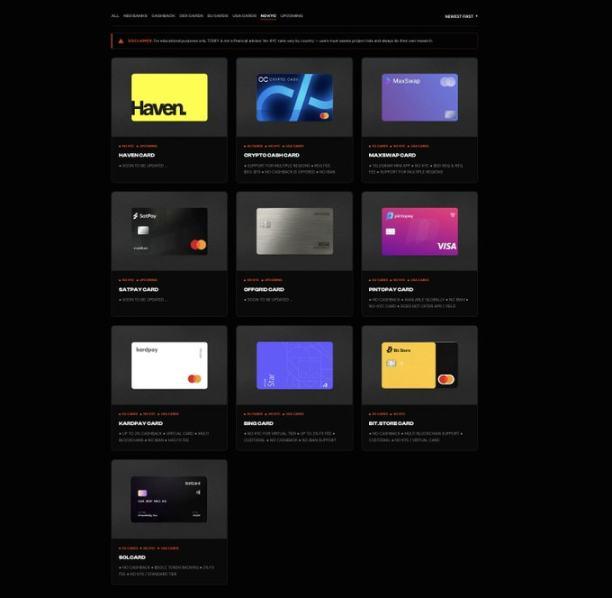

Currently, "KYC-free" card marketing projects fall into two categories: prepaid cards and so-called "business" cards. Business cards rely on various variations of the aforementioned corporate card loopholes; the name may change, but the structure remains the same.

A non-exhaustive list of currently marketed "KYC-free" cards (covering prepaid and business card models) can be found on the website .

For example, including:

- Offgrid.cash

- Bitsika

- Goblin Cards

- Bing Card

- Similar "cryptocurrency cards" distributed via Telegram or by invitation only.

Case Study: SolCard

SolCard is a prime example. After its KYC-free mode was launched and gained attention, it was forced to switch to full KYC. Accounts were frozen until users provided their identity information, and the initial vision of privacy collapsed overnight.

The project eventually shifted to a hybrid structure: a prepaid card with a very low credit limit that requires no KYC verification, and a card with full KYC verification. The original no-KYC card model could not survive after attracting substantial usage; this was an inevitable result of operating on incompatible tracks.

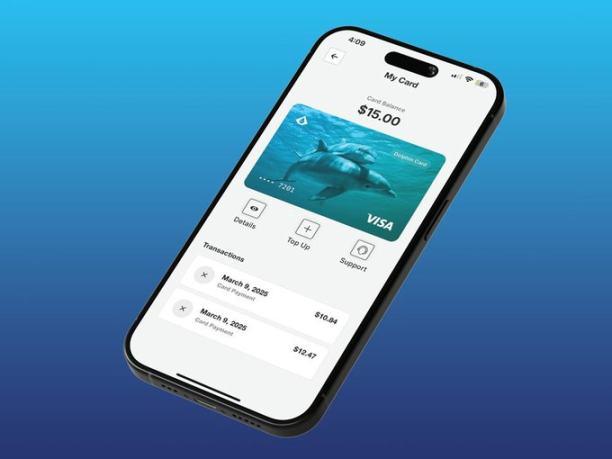

Case Study: Aqua Wallet's Dolphin Card

In mid-2025, Aqua Wallet, a Bitcoin and Lightning Network wallet developed by JAN3, launched the Dolphin Card. It was released as a limited beta version, open to 50 users, and required no identity documents. Users could deposit Bitcoin or USDT, with a spending limit of $4,000.

This upper limit is itself very enlightening—it is explicitly designed to reduce regulatory risks.

Structurally, the Dolphin card combines a prepaid model with a corporate account setup. The card operates through a company-controlled account, rather than a personal bank account.

It worked fine for a while, but not forever.

In December 2025, the project was abruptly suspended due to an "unexpected problem" with the card provider. All Dolphin Visa cards were immediately invalidated, and any remaining balances required manual refunds via USDT, without further explanation.

Risks faced by users

When these projects collapse, it is the users who bear the cost.

Funds may be frozen indefinitely, and refunds may require cumbersome manual processes. Sometimes, the entire balance can be lost. There is no deposit insurance, no consumer protection, and no legal recourse against the issuing bank.

What's particularly dangerous is that many operators knew this outcome beforehand, yet they still went ahead with it. Others used rhetoric like "proprietary technology," "regulatory innovation," or "new infrastructure" to mask the risks.

Issuing company cards to fake employees involves no "proprietary technology" whatsoever.

To put it kindly, it's ignorance; to put it bluntly, it's blatant exploitation.

Prepaid cards and gift cards: Which ones are truly viable?

Legitimate non-KYC payment tools exist, but they have strict limitations.

Prepaid cards purchased through compliant providers are legal because they have extremely low spending limits, are designed for small transactions, and don't pretend to offer unlimited spending. Examples include prepaid cryptocurrency cards offered through platforms like Laso Finance.

(Screenshot from @LasoFinance website)

Gift cards are another option; services like Bitrefill allow users to privately purchase gift cards from mainstream merchants using cryptocurrency, which is perfectly legal and compliant.

(Screenshot from @bitrefill website)

These tools are effective because they respect regulatory boundaries, rather than pretending they don't exist.

The core issue of misrepresentation

The most dangerous claim is not about "KYC-free" itself, but about permanence.

These projects imply that they have "solved" the problem, discovered a "structural vulnerability," and that their technology renders compliance "irrelevant."

That's not the case.

Visa and Mastercard don't negotiate with startups; they just enforce the rules.

Any product that promises high credit limits, is top-upable, is globally accepted, requires no KYC, and displays the Visa or Mastercard logo is either making a false statement about its structure or is planning to disappear in the near future.

There is no "proprietary" technology that can bypass this fundamental requirement.

Some operators argue that KYC will eventually be introduced through "zero-knowledge proofs," so that the company itself never directly collects or stores user identities. But this doesn't solve the fundamental problem. Visa and Mastercard don't care "who" sees the identity information; they require that identity information be documented and accessible to the issuing bank or compliance partners in the event of an audit, dispute, or enforcement action.

Even if authentication is done through privacy-protected credentials, the issuer must still have access to a clear and readable record at some point in the compliance system. This is not "KYC-free".

What would happen if we bypassed the duopoly?

(Screenshot from @colossuspay website)

There is a type of card-based payment system that has fundamentally changed the game: systems that do not rely on Visa or Mastercard at all.

Colossus Pay is an example of this approach.

It does not issue cards through licensed banks, nor does it route transactions through traditional card networks. Instead, it operates as a native, encrypted payment network that connects directly with merchant acquiring institutions. Acquiring institutions are entities that own merchant relationships and control the point-of-sale payment terminal software; there are only a handful of such institutions globally, such as Fiserv, Elavon, and Worldpay.

By integrating at the acquiring layer, Colossus completely bypasses the issuer and card network stack. Stablecoins are routed directly to the acquiring institution, converted as needed, and settled to the merchant. This reduces fees, shortens settlement time, and eliminates the "pass-through fees" charged by Visa and Mastercard for each transaction.

The key point is that, since no issuing bank or card network is involved in the transaction flow, there is no entity contractually required to conduct end-user KYC for card issuance. Under the current regulatory framework, the only entity with KYC obligations in this model is the stablecoin issuer itself. The payment network doesn't need to invent loopholes or misclassify users because it doesn't operate under card network rules in the first place.

In this model, the "card" is essentially just a private key for authorizing payments. KYC-free access is not the goal; it's merely a natural byproduct of removing the duopoly and its associated compliance structures.

This is the structurally honest path to non-KYC payment tools.

If this model is feasible, then the obvious question is: why hasn't it become widespread?

The answer is distribution.

It's very difficult to integrate with single-institutional clients. They are conservative entities that control the terminal operating system and are slow to act. Integrating at this layer requires time, trust, and operational maturity. But this is also where real change can happen, because it's this layer that controls how the real world accepts payments.

Most cryptocurrency card startups opted for the easier path: integrate with Visa or Mastercard, launch aggressive marketing campaigns, and expand rapidly before law enforcement arrives. Building outside of a duopoly is slower and more difficult, but it's the only path that won't end in "shutdown."

Conceptually, this model collapses a credit card into a cryptographic primitive. The card is no longer an account issued by a bank, but a private key authorizing payments.

in conclusion

As long as Visa and Mastercard remain the underlying infrastructure, unlimited spending without KYC is impossible. These restrictions are structural, not technical, and no amount of branding, storytelling, or fancy terminology can change this reality.

When a card bearing the Visa or Mastercard logo promises high credit limits and KYC waivers, the explanation is simple: it either exploits a corporate card structure to place the user outside the legal relationship with the bank, or it misrepresents how the product actually works. History has repeatedly proven this.

The truly safer options are prepaid cards and gift cards with limited limits, which have clear caps and expectations. The only lasting, long-term solution is to completely abandon the Visa-Mastercard duopoly. Everything else is temporary, fragile, and exposes users to risks they often don't realize until it's too late.

Over the past few months, I've seen a dramatic increase in discussion about "KYC-free cards." I'm writing this because there's a huge knowledge gap regarding how these products actually work and the legal and escrow risks they pose to users. I have nothing to sell; I'm writing about privacy because it matters, regardless of the area it touches upon.