This article aims to explain the basic principles of exchange solvency proof and further explore more possibilities in between CEX and DEX at both ends of the asset custody spectrum.

Original text: Having a safe CEX: proof of solvency and beyond (vitalik.ca)

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: DoubleSpending (@doublespending)

Review: ECN

Cover: Photo by Pawel Czerwinski on Unsplash

Special thanks to Balaji Srinivasan and the Coinbase, Kraken, and Binance teams for discussions.

Whenever a large centralized exchange collapses, a question that often comes up is: Can we use cryptography to solve this problem? Exchanges can create cryptographic proofs to prove that the funds they hold on the chain are sufficient to repay users, rather than relying solely on "fiat" solutions such as government licenses, auditors, corporate governance investigations, and background checks on exchange legal persons.

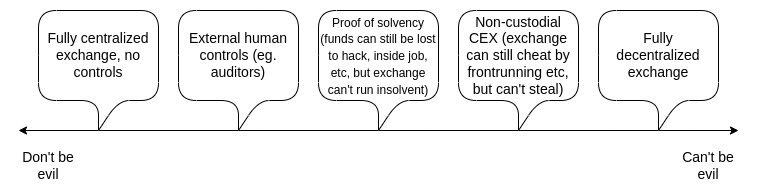

More ambitiously, exchanges could build a system where depositors’ funds cannot be withdrawn without their consent. We can try to explore the line between professional CEXs that “don’t do evil” and inefficient on-chain DEXs that “can’t do evil” but leak privacy. This post will delve into historical attempts to make CEXs more trustless, the limitations of the technology they use, and some powerful means that rely on advanced technologies such as ZK-SNARKs.

Balance Tables and Merkle Trees: Traditional Proofs of Repayability

The earliest attempts by exchanges to use cryptography to prove that they didn’t cheat their users date back a long time. In 2011, MtGox, the largest Bitcoin exchange at the time, proved that they owned the funds by sending a transaction that moved 424,242 BTC to a pre-published address. In 2013, people began to discuss how to solve the other side of the problem: proving the total size of user deposits. If you prove that a user’s deposit is equal to X (proof of liabilities) and prove that you have the private keys to X tokens (proof of assets), then you provide proof of solvency: you prove that the exchange has enough funds to repay depositors.

The simplest way to provide proof of deposit is to publish a list. Every user can check their balance in the list, and anyone can check the complete list: (i) every balance is non-negative; and (ii) the total is the amount claimed.

Of course, this would destroy privacy, so we could change the scheme a bit: publish a list and send the salt value to the user privately. But even this would leak the balance and its distribution. To protect privacy, we use a follow-up technology: Merkle tree technology.

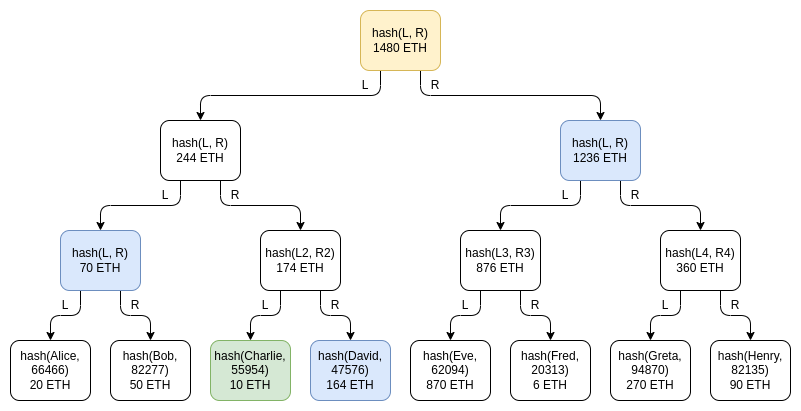

Green: Charlie’s node. Blue: The node Charlie received for proof. Yellow: The root node, announced to everyone.

Merkle tree technology puts the user balance table into a Merkle sum tree. In the Merkle sum tree, each node is a pair. The bottom leaf nodes represent the balance of each user and the salted hash of the username. In each higher level node, the balance is the sum of the balances of the two nodes below, and the hash is the hash of the two nodes below. The Merkle sum proof is the same as the Merkle proof, which is a "branch" consisting of all sister nodes on the path from the leaf node to the root node.

First, the exchange sends each user a Merkle sum proof of their balance. The user is then able to be sure that their balance is correctly included as part of the total. A simple example code can be found here.

# The function for computing a parent node given two child nodesdef combine_tree_nodes(L, R):L_hash, L_balance = LR_hash, R_balance = Rassert L_balance >= 0 and R_balance >= 0new_node_hash = hash(L_hash + L_balance.to_bytes(32, 'big') +R_hash + R_balance.to_bytes(32, 'big'))return (new_node_hash, L_balance + R_balance)# Builds a full Merkle tree. Stored in flattened form where# node i is the parent of nodes 2i and 2i+1def build_merkle_sum_tree(user_table: "List[(username, salt, balance)]"):tree_size = get_next_power_of_2(len(user_table))tree = ([None] * tree_size +[userdata_to_leaf(*user) for user in user_table] +[EMPTY_LEAF for _ in range(tree_size - len(user_table))])for i in range(tree_size - 1, 0, -1):tree[i] = combine_tree_nodes(tree[i*2], tree[i*2+1])return tree# Root of a tree is stored at index 1 in the flattened formdef get_root(tree): return tree[1]# Gets a proof for a node at a particular indexdef get_proof(tree, index):branch_length = log2(len(tree)) - 1# ^ = bitwise xor, x ^ 1 = sister node of xindex_in_tree = index + len(tree) // 2return [tree[(index_in_tree // 2**i) ^ 1] for i in range(branch_length)]# Verifies a proof (duh)def verify_proof(username, salt, balance, index, user_table_size, root, proof):leaf = userdata_to_leaf(username, salt, balance)branch_length = log2(get_next_power_of_2(user_table_size)) - 1for i in range(branch_length):if index & (2**i):leaf = combine_tree_nodes(proof[i], leaf)else:leaf = combine_tree_nodes(leaf , proof[i])return leaf == root

The privacy leakage under this design is much lower than that of publicly disclosing the complete balance table, and the risk of privacy leakage can be further reduced by disrupting each branch every time the Merkle root is released, but there are still some privacy leakage issues: Charlie knows that someone's balance is 164 ETH, the total balance of two users is 70 ETH, etc. An attacker who controls multiple accounts can still learn a lot of information about exchange users.

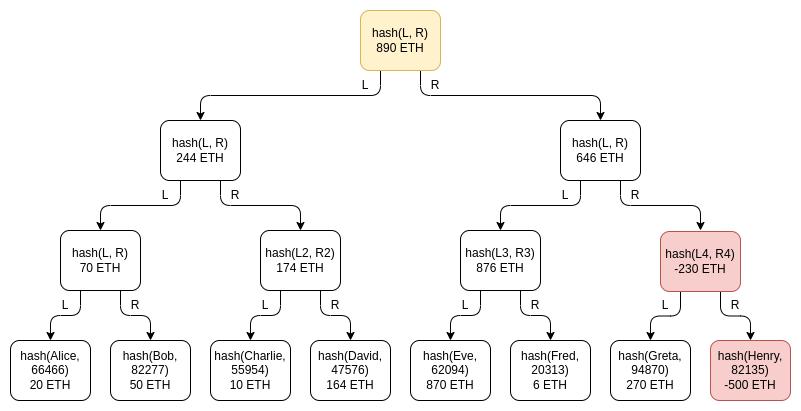

An important subtlety of this scheme is the possibility of negative balances: what if an exchange with 1390 ETH user balances but only 890 ETH in reserves tries to make up the difference by adding a -500 ETH balance under a fake account somewhere in the tree? This possibility doesn't actually break the scheme, which is why we specifically use a Merkle sum tree instead of a regular Merkle tree. Assume that Henry is a fake account controlled by the exchange, and the exchange puts -500 ETH on it:

Greta's verification will fail: when the exchange will have to give her Henry's node with a balance of -500 ETH, she will reject the invalid node. Eve and Fred will also fail verification because the intermediate node above Henry has a balance of -230 ETH, so this node is also invalid! In order for the theft to go undetected, the exchange can only hope that no one in the right half of the tree checks its balance proof.

If the exchange can pick out users with 500 ETH who don't bother to check their balance proofs, or who are not believed when they complain about not receiving a balance proof, then the exchange can get away with it. However, the exchange can also achieve the same effect by excluding these users from the Merkle sum tree. So, if we only look at proof of debt, Merkle tree technology basically meets the needs. But its privacy properties are still not ideal. You can use Merkle trees more cleverly to improve, such as making satoshi or wei a separate leaf node. However, by using more advanced technology, you can do better.

Using ZK-SNARKs to improve privacy and robustness

ZK-SNARKs are a powerful technology. ZK-SNARKs are to cryptography what AI is: a general-purpose technology that can outperform a range of specialized techniques developed decades ago to solve a range of problems. So, of course we can use ZK-SNARKs to greatly simplify and improve privacy in proof-of-debt protocols.

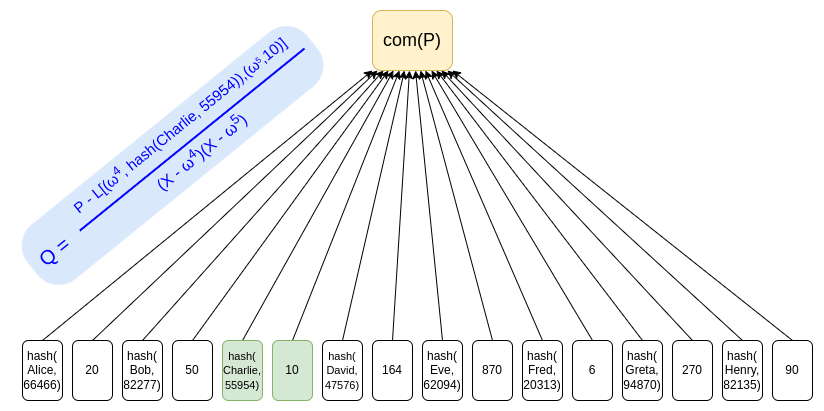

We can simply put all users' deposits into a Merkle tree (or more simply a KZG commitment) and use ZK-SNARK to prove that all balances in the tree are non-negative and add up to some claimed value. If we add a layer of hashing to ensure privacy, then the Merkle branch (or KZG proof) sent to each user will not reveal any other user's balance.

Using KZG commitments is one way to avoid privacy leaks because it does not require "sister nodes" to be provided as proof, and a simple ZK-SNARK can be used to prove the sum of the balances and that each balance is non-negative.

We can prove the sum of the balances in the above KZG and their non-negativity through a dedicated ZK-SNARK. Here is a simple example. We introduce an auxiliary polynomial I(x) that "builds up every bit of the user's balance" (for the sake of example, we assume the balance is less than 215), where every 16th position tracks the difference and ensures that the value will only be 0 if the actual total is equal to the declared total. If z is a primitive root of order 128, we can prove that the equation holds:

How to convert these equations to polynomial proofs and subsequently to ZK-SNARKs can be found in my articles on ZK-SNARKs here and elsewhere. This is not an optimal protocol, but it makes these cryptographic proofs a little easier to understand!

With just a few additional equations, the constraint system can be adapted to more complex settings. For example, in a leveraged trading system, it is acceptable for individual users to have negative balances, but only if they have enough collateral to cover their liabilities. SNARKs can be used to prove this more complex constraint, assuring users that exchanges cannot secretly exempt certain users and jeopardize their assets.

In the long run, this ZK proof of liability could be useful beyond user deposits in exchanges, and could be used for a wider range of lending scenarios. Anyone taking out a loan would put a record of that loan into a polynomial or tree, with the root published on-chain. This would allow anyone seeking a loan to provide a zero-knowledge proof to the lender that they haven’t taken out too many other loans. Eventually, legal innovations could even allow loans committed in this way to have higher priority than uncommitted loans. This aligns with an idea we discussed in Decentralized Society: Finding the Soul of Web3: making the concept of negative reputation on-chain possible through some form of “soul-bound token.”

Proof of assets

The simplest version of proof of assets is the protocol we saw above: to prove that you hold X tokens, you simply move X tokens at a predetermined time or carry a message in the transaction that "these funds belong to Binance". To avoid paying transaction fees, you can sign an off-chain message. Both Bitcoin and Ethereum have standards for off-chain signature messages.

There are two practical problems with this simple proof-of-asset technique:

● Cold wallet processing

● Collateral reuse

For security reasons, most exchanges store the majority of user funds in cold wallets: on offline computers, transactions need to be signed manually and carried to the internet. This approach is common: the cold wallet I used to store my personal funds was on a permanently offline computer, which would generate QR codes containing signed transactions, which I would then scan with my phone. Due to the large amount of funds, the security protocols used by exchanges are more complex, often involving multi-party computations across multiple devices to further reduce the possibility of a single device being hacked and leaking keys. In this context, even creating an extra message to prove control of an address is an expensive operation!

The exchange can adopt the following methods:

● Maintain a few public addresses for long-term use. The exchange generates a number of addresses, publishes proof of ownership of each address only once, and then reuses these addresses. This is by far the simplest solution, although it adds some restrictions to protect security and privacy.

● Hold many addresses, then prove a few randomly. Exchanges hold many addresses, and it may even be possible that each address is used only once and never again after a single transaction. In this case, the exchange needs to have a protocol to randomly select a few addresses from time to time that the exchange must "open" to prove ownership. Some exchanges have done something similar with auditors, but in principle, this technique could be turned into a fully automated process.

● More complex ZKP methods. For example, an exchange could set up 1/2 multi-signatures for all of its addresses, where one of the keys is different for each address, and the other identical key is an important emergency backup blinded version stored in some complex but secure way (e.g., 12/16 multi-signature). To protect privacy and avoid leaking all of its addresses, the exchange could even run a zero-knowledge proof on the blockchain to prove the total balance of the addresses on the chain in that format.

Another major issue is preventing collateral reuse. It is often easy for exchanges to transfer collateral back and forth between each other to prove reserves, allowing exchanges to get away with not actually being solvency. Ideally, solvency proofs should be done in real time, with proofs updated after every block. If this is impractical, the next best thing would be for exchanges to coordinate a fixed time to do proofs, such as proving reserves every Tuesday at 2pm UTC.

The final question is: can proof of assets be done on fiat currency? Exchanges hold not only cryptocurrencies, but also fiat currencies within the banking system. In this regard, the answer is yes, but such a program will inevitably rely on the "fiat currency" trust model: banks themselves can prove balances, auditors can prove balance sheets, etc. Given that fiat currencies cannot be verified through cryptography, this is the best solution within this framework and is still worth doing.

Another approach is to separate entity A from entity B, where A is responsible for running the exchange and handling stablecoins such as USDC, which are backed by some asset; and B is responsible for handling the inflow and outflow of cash between cryptocurrencies and the traditional banking system, in this case B is USDC itself. Since the "liabilities" of USDC are just ERC20 tokens on the chain, proof of liabilities can be "easily" obtained, and we only need to deal with the problem of proof of assets.

Plasma and validiums: Can we achieve a non-custodial CEX?

Let’s say we want to go a step further: we don’t want to just prove that an exchange has enough funds to repay its users. Instead, we want to prevent exchanges from stealing users’ funds altogether.

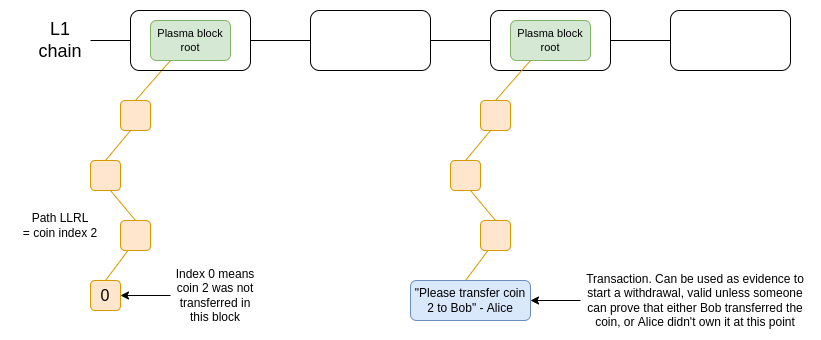

The first to try this was Plasma, a scaling solution that became popular in the Ethereum research community in 2017 and 2018. Plasma works by splitting balances into a set of independent "tokens", each of which is assigned an index and placed in a specific position in the Plasma block's Merkle tree. To make a valid token transfer, the transaction needs to be placed in the correct position in the tree, and the root of the tree is published on the chain.

A simplified diagram of a version of Plasma. Tokens are held in a smart contract that enforces the rules of the Plasma protocol when withdrawals are made.

OmiseGo attempted to create a decentralized exchange based on this protocol, but since then they have moved on to other things - for that matter, so did Plasma Group, which worked on the optimistic rollup project Optimism.

Since the peak of Plasma discussions in 2018, ZK-SNARKs have become increasingly viable for scaling-related use cases, and as we said above, ZK-SNARKs change everything.

The newer version of Plasma is what Starkware calls validium: essentially the same as ZK-rollup, except the data is kept off-chain. This construction is suitable for many use cases, and can conceivably be applied to any scenario where a centralized server needs to prove that it is executing code correctly. In validium, the operator cannot steal funds, but depending on the specific implementation details, some user funds may be stuck if the operator disappears.

Now this all seems great: far from being an either/or choice between CEX and DEX, it turns out there’s a spectrum of options, including various forms of hybrid centralization, where you get some benefits, like efficiency, but still have a lot of cryptographic safeguards that prevent most forms of malicious behavior from centralized operators.

However, it’s worth thinking about the remaining fundamental question: How to handle user error. By far the most important type of error is: What if a user forgets their password, loses their device, gets hacked, or loses access to their account?

Exchanges can work around this by first leveraging email recovery, and if that fails, more complex recovery via KYC. But to solve these problems, exchanges need to actually control the tokens. To be able to properly restore user funds, exchanges need to have the same power they can use to steal user funds without cause. This is an unavoidable tradeoff.

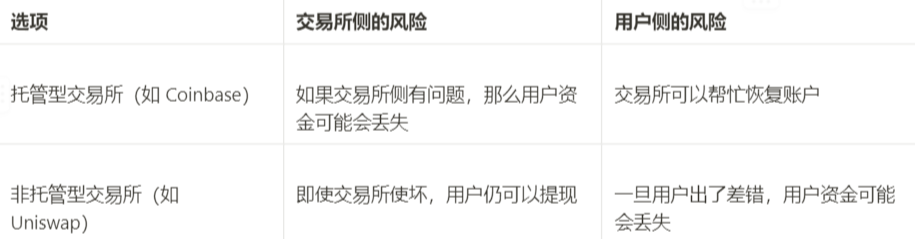

The ideal long-term solution is to rely on self-custody, where users can easily use technologies such as multi-signature and social recovery wallets to help handle emergencies in the future. In the short term, there are two obvious alternatives with different costs and benefits:

Another important issue is cross-chain support: exchanges need to support many different chains. Systems such as Plasma and validiums need to be coded in different languages to support different platforms and cannot be implemented on some platforms (especially Bitcoin) in their current form. This is expected to be solved through technical upgrades and standardization; however, in the short term, this is another reason why today’s custodial exchanges maintain a custodial model.

Conclusion: Looking to the Future for Better Exchanges

In the short term, there are two clear categories of exchanges: custodial and non-custodial. Today, the latter category is DEXs like Uniswap, and in the future we may also see CEXs governed by cryptography, where user funds are held in a manner similar to validium smart contracts. We may also see semi-custodial exchanges, where we trust them to handle fiat but not crypto.

Both types of exchanges will continue to exist, and the easiest way to improve the security of custodial exchanges for backward compatibility is to add proof of reserves. This includes a combination of proof of assets and proof of liabilities. There are still some challenges in designing good protocols for both, but we can and should promote the development of both types of technology in parallel and open source software and programs as much as possible so that all exchanges can benefit.

In the long term, I hope we move towards a situation where all exchanges are non-custodial, at least in crypto. Wallet recovery will exist, and there may need to be highly centralized recovery options for new users with small amounts of funds and institutions that require such arrangements for legal reasons, but this can be done at the wallet level rather than within the exchange. On the fiat side, movement between the traditional banking system and the crypto ecosystem can be accomplished through the money in and out process native to asset-backed stablecoins such as USDC. However, we still have a long way to go.

[1] Translator’s note:➤ Every 16 digits represent a user (the first 15 digits represent the user's balance, and the last digit represents the difference between the total balance of the user so far and the declared balance). We can see that the above example represents two users (readers need to have some insight here)

➤ Claimed average user balance: 185

➤ User 1's balance: 20 -> 000 0000 0001 0100

Difference: 20 – 185 = -165

➤ User 2's balance: 50 -> 000 0101 0011 0010

Difference: -165 + 50 -185 = -300

➤ Finally, after traversing all users, the balance requirement for the last user is 0

➤ Explanation of the four equations

Equation 1: The initial value of the recursion is 0

Equation 2: Each user’s balance needs to correspond to the KZG commitment

Equation 3: Recursive formula for each user's balance, constraining balance >= 0 and < 214

(The above statement that balance < 215 is probably a typo, because according to equation 3, the recursive formula has only 14 values, I(zi) < 214,

16 numbers correspond to: I(z{16x})=0| I(z{16x+1}) | I(z{16x+2}) | … | I(z{16x+14}) | Difference

The maximum value corresponding to the 16 numbers is: 0 | 21 -1 | 22 -1 | … | 214 -1 | difference)

Equation 4: Constraining the total balance of all users to be consistent with the balance declared by the exchange

Special thanks to ECN community translation volunteer @doublespending for his translation contribution to this article.

Disclaimer: As a blockchain information platform, the articles published on this site only represent the personal opinions of the author and the guest, and have nothing to do with the position of Web3Caff. The information in the article is for reference only and does not constitute any investment advice or offer. Please comply with the relevant laws and regulations of your country or region.