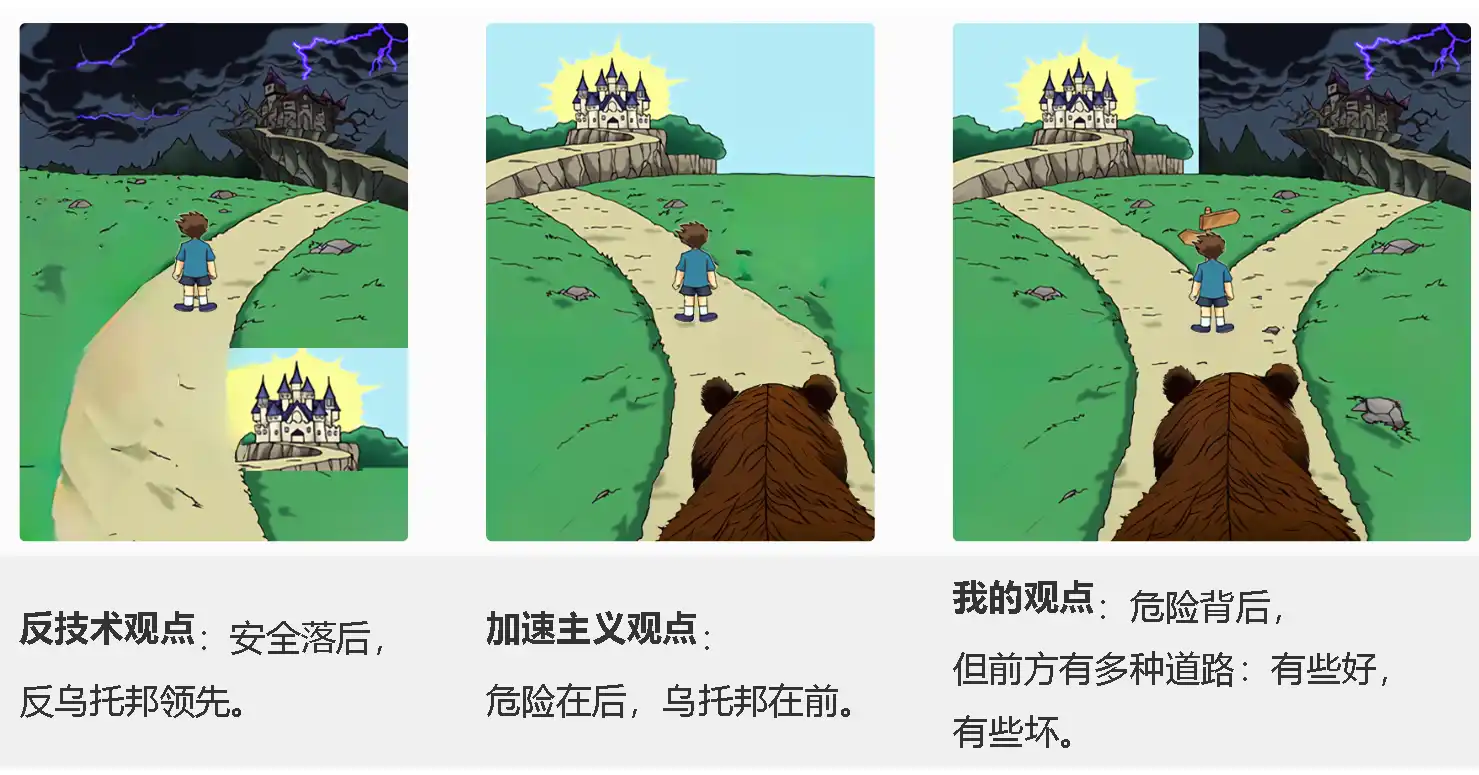

It is a commonplace to talk about the impact that technological progress will have on the future. Last month, Marc Andreessen's "Declaration of Technological Optimism" clearly opposed the fear of technological progress. In addition, this month's controversy caused by OpenAI, the topic has once again aroused heated discussion.

Vitalik Buterin opposed the mentality of "prioritizing maintaining the current state of the world" and pointed out that technological development not only needs to focus on intensity, but also on direction. In his latest article, he deeply discussed the intersection of artificial intelligence and blockchain, and proposed the concept of "d/acc" (decentralized acceleration). He believes that with the accelerated development of technology, the emergence of artificial intelligence may become one of the biggest challenges facing mankind, but it also proposes a more humane and decentralized development path.

The topics covered in the article cover information defense, social technology, human-machine cooperation and other aspects, highlighting the importance of actively guiding the direction of technological development. In a different philosophical context, Vitalik advocates an attitude that is both positive and cautious, calling on developers to pay more attention to choices and intentions when building technology to ensure that the development of technology is in line with human values and long-term interests.

Special thanks to Morgan Beller, Juan Benet, Eli Dourado, Sriram Krishnan, Nate Soares, Jaan Tallinn, Vincent Weisser, Balvi volunteers and others for their feedback and reviews.

Last month, Marc Andreessen published his "Techno-optimist Manifesto," calling for a renewed enthusiasm for technology while advocating the use of market and capitalist means to build technology and push humanity toward a brighter future. The manifesto explicitly rejects the so-called stagnation mentality, which is the fear of technological progress and prioritizes keeping the world as it is today. This declaration has received widespread attention, including responses from Noah Smith, Robin Hanson, Joshua Gans (positive attitude), Dave Karpf, Luca Ropek, Ezra Klein (more negative attitude) and others. Although not directly related to the manifesto, similar topics include James Pethokoukis' "Conservative Futurism" and Palladium's "It's Time to Build for Good." This month, we're seeing a similar debate through the OpenAI controversy, with much of the discussion focused on the dangers of super artificial intelligence and the possibility that OpenAI may be moving too fast.

Extended reading: The real reason why Sam Altman was seized of power? OpenAI Board of Directors Received Warning: New AI Threats All Humanity

My sense of technological optimism is warm and nuanced. I believe that the future will be brighter than the present because of radically changing technologies, and I also believe in humans and humanity. I object to the mentality that we should try to keep the world basically the same as it is today, with just less greed and more public health care. But on this basis, I think not only the degree is important, but the direction is also crucial. Certain types of technology can directly make the world a better place, while some, if developed, may mitigate the negative impacts of other types of technology. Currently, the world is overinvested in some directions of technological development and underinvested in others. We need to consciously choose the direction we want because the formula of "maximizing profits" does not automatically lead to these directions.

In this article, I’ll explore what techno-optimism means to me. This includes the broader worldview that inspires my work on certain types of blockchain and cryptography applications, social technology, and other scientific areas that interest me. But different views on this issue also have important implications for artificial intelligence and many other fields. Our rapid advances in technology may well become the most important social issue of the 21st century, so it makes sense to think carefully about this issue.

Technology is amazing, and delaying its development can be extremely costly.

In some areas, people generally underestimate the benefits of technology, viewing it as a utopia and a source of potential risk. Over the past half century, this view has often been driven by environmental concerns or concerns that the benefits of technology will flow only to the rich, consolidating their power over the poor. Lately, I've also noticed that some libertarians are worried about certain technologies that may lead to the concentration of power. This month, I did some research on the following question: If a technology needed to be restricted because it was too dangerous, would people rather have it monopolized or delayed for a decade? To my surprise, across the three platform and three monopoly status options, people unanimously and strongly chose deferral.

So I sometimes worry that we may be overcorrecting, and that many people are overlooking another side of the debate: that the benefits of technology are indeed huge, and in areas where we can measure them, the positive effects far outweigh the negative ones, even if they are delayed by a decade The cost is also incalculable.

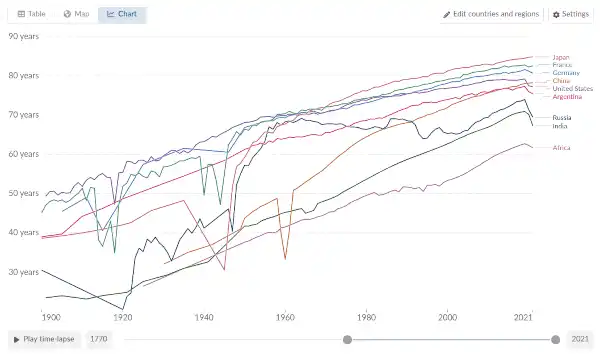

As a concrete example, let’s look at a life expectancy graph:

What did we see? Over the past century, truly tremendous progress has been made. This applies to the entire world, both historically wealthy and dominant regions and poor and exploited regions.

Some blame technology for creating or exacerbating disasters, such as totalitarianism and war. In fact, we can see on the graph the deaths caused by war: during World War I (1910s) and during World War II (1940s). If you look closely, you can also see non-military disasters such as the Spanish Flu and the Great Leap Forward. But the graph makes one thing clear: Even as horrific as those disasters were, they were overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the improvements made in food, sanitation, medicine, and infrastructure during that century.

This is consistent with significant improvements in our daily lives. Thanks to the Internet, most people around the world now have easy access to information that was unavailable twenty years ago. The global economy has become more accessible due to improvements in international payments and finance. Global poverty is declining rapidly. With online maps, we no longer have to worry about getting lost in the city, and we now have an easier way to hail a ride if we need to get home quickly. Our possessions have become digital and physical objects have become cheaper, which means we no longer worry as much about physical theft. Online shopping has reduced inequalities in access to goods between major global cities and the rest of the world. In every aspect, automation brings us that eternally underestimated benefit of simply making our lives more convenient.

These improvements, both quantifiable and non-quantifiable, are huge. And in the 21st century, it's very likely that even greater improvements will come soon. Today, ending aging and disease seems like a utopian concept. But from the perspective of computers in 1945, the modern era of embedding chips into almost everything was once utopian. After all, even computers in science fiction movies were usually room-sized. If biotechnology advances in the next 75 years as much as computers have advanced in the past 75 years, the future may be more impressive than almost anyone expects.

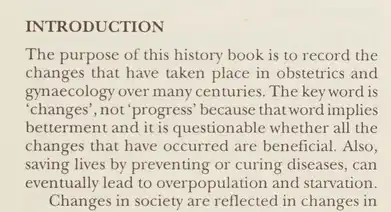

At the same time, some skepticism about progress often takes a darker direction. Even medical textbooks, such as this one from the 1990s (thanks to Emma Szewczak for finding it), sometimes make extreme claims that deny the value of two centuries of medical science and even argue that saving human life is not a Good thing:

The "limits to growth" theory is an idea put forward in the 1970s, arguing that growing population and industry will eventually exhaust the earth's limited resources, leading to China's one-child policy and India's large-scale forced sterilization. In earlier times, concerns about overpopulation were used to justify mass murder. And these ideas, which have been advanced since 1798, have been proven wrong over a long period of time.

It's for these reasons that I've come to feel very uncomfortable with arguments for slowing technological or human progress. Even sectoral slowdowns can be dangerous given the close connections between sectors. So it is with a heavy heart that I speak with a heavy heart as I write what I will explore next, departing from a stance of being open to progress in whatever form it takes. However, the 21st century is so different and unique that these subtleties are worth considering.

Having said that, in terms of the broader question, especially when we move beyond "is technology good overall" and toward "what specific technologies are good?", there is an important nuance to point out: environment .

The importance of environment and willingness to coordinate

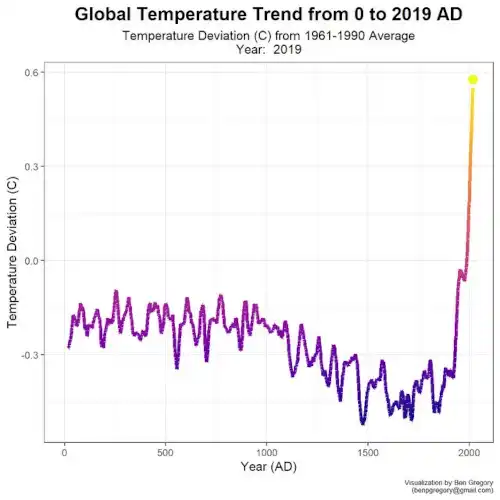

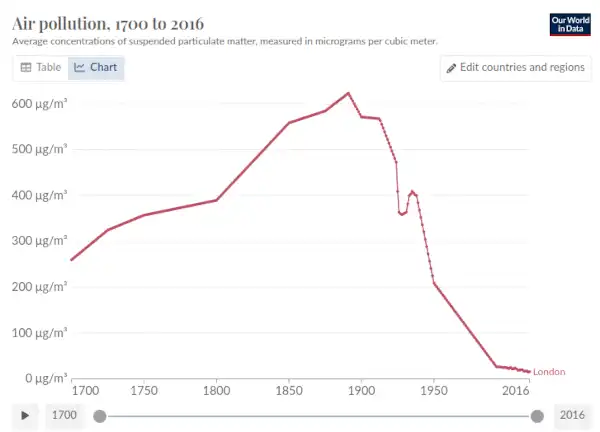

Progress has been made in almost every aspect over the past hundred years, with the exception of climate change:

Even a pessimistic scenario for rising temperatures would fall far short of actual human extinction. But such a scenario could kill more people than a major war and could severely damage the health and livelihoods of people in areas already most troubled. A study by the Swiss Re Institute suggests that the worst-case climate change scenario could reduce the gross domestic product of the world's poorest countries by up to 25%. The study also noted that life expectancy in rural India could be a decade lower than originally expected, while studies like this and this one suggest climate change could lead to 100 million more deaths by the end of the century.

These problems are very serious. The answer to why I am optimistic about our ability to overcome these challenges is two-fold. First, after decades of hyperbole and wishful thinking, solar is finally turning a corner, and supporting technologies like batteries are making similar progress. Second, we can look at humanity’s record in solving previous environmental problems, taking air pollution as an example. Dystopias of the past: The London Smog in 1952 London.

What has happened since then? We asked Our World In Data again:

It turns out that 1952 wasn't even the peak of air pollution: higher concentrations of air pollutants were even considered normal and acceptable in the late 19th century. Since then, we have witnessed a sustained and rapid decline in air pollution over the course of a century. I have experienced this process first hand, when I visited China in 2014, the air was filled with high concentrations of smog, and it was normal to estimate that life expectancy would be shortened by more than five years, but in 2020, the air often looks as clean as in many Western cities. This isn't our only success story. In many parts of the world, forest area is increasing. The acid rain crisis is improving. The ozone layer has been recovering for decades.

To me, the moral of this story is that oftentimes, version N of the technology our civilization has does cause a problem, and version N+1 solves it. However, this does not happen automatically and requires conscious human effort. The ozone layer is recovering because we brought it back through international agreements like the Montreal Protocol. Air pollution is improving because we are making it better. Likewise, solar panels have made huge strides not because they were a destined part of the energy technology tree, but because decades of recognition of the importance of addressing climate change have inspired engineers to work on the problem, and Companies and governments fund their research. Solving these problems is achieved through conscious action, shaping the views of governments, scientists, philanthropists and businesses through public discourse and culture, rather than the unstoppable "technological capital machine".

Artificial intelligence is fundamentally different from other technologies and requires special care

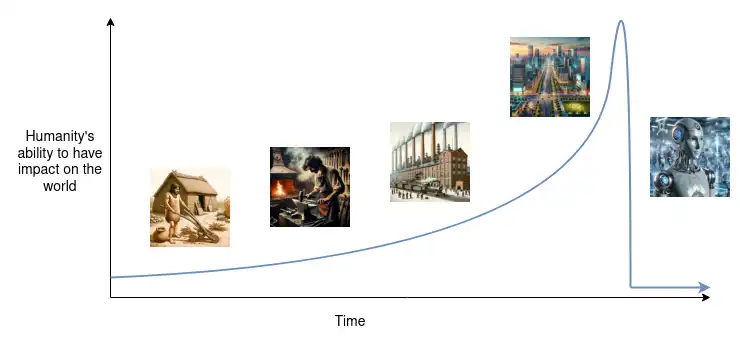

A lot of the dismissive view of AI I see comes from the perspective that it’s just “yet another technology”: the same type as social media, encryption, contraception, phones, airplanes, guns, printing, and the wheel. things. These things obviously have a significant impact on society. They are not just isolated improvements to individual happiness, they fundamentally change culture, alter the balance of power, and harm those who were heavily dependent on the previous order. Many people are against them. Overall, the pessimists were invariably proven wrong.

But there is a different way of looking at artificial intelligence, which is that it is a new type of thinking that is rapidly improving the level of intelligence, perhaps even surpassing human intelligence and becoming the new top species on the planet. In this approach, much smaller things are covered, including humans surpassing monkeys, multicellular organisms surpassing single-celled organisms, the origins of life itself, and perhaps the Industrial Revolution, in which mechanical devices surpassed in physical strength Humanity. Suddenly, it felt like we were walking in unfamiliar territory.

What's important is that there are risks

In the scenario where something goes wrong with AI and could make the world a worse place, the worst-case scenario (an almost painful risk) is that it could actually lead to the extinction of the human race . This is an extreme statement: although the worst-case scenarios from climate change, man-made pandemics, or nuclear war may cause great harm, there are still many "islands" of civilization that will remain intact to pick up the wreckage. But if a super-intelligent AI decides to turn against us, it's likely that there won't be any survivors left, thus ending humanity permanently. Even Mars may not be safe.

One reason for concern centers on tool convergence: for the very broad class of goals a superintelligent entity might have, two very natural intermediate steps an AI might take to better achieve those goals are (i) consuming resources and (ii) ensure their own safety. The Earth contains vast resources, and humans pose a predictable threat to the security of such an entity. We can try to give the AI a clear goal, which is to love and protect humans, but we don't know how to achieve that goal in a way that doesn't completely break down when the AI encounters something unexpected. So we are faced with a problem.

A 2022 survey of machine learning researchers showed that the average researcher believes that the probability that artificial intelligence will actually kill us all is between 5-10%, roughly the same as if you died from non-biological causes (such as injuries) Expected chances are comparable.

This is just a speculative hypothesis, and we should all be wary of speculative hypotheses that involve complex, multi-step stories. However, these arguments have withstood more than a decade of scrutiny and, therefore, seem worthy of some mild concern. But even if you're not worried about actual extinction, there are other reasons to worry.

Even if we survive, is a future of super-intelligent AI the world we want to live in?

Many modern science fiction novels depict dystopian scenarios and portray artificial intelligence poorly. Even when non-sci-fi works attempt to explore possible artificial intelligence futures, the answers are often quite unsatisfactory. So I asked around and asked about depictions of a future involving superintelligent AI, whether science fiction or otherwise, and whether we would want to live in it. By far the most common answer is Iain Banks' Civilization series.

The "Civilization Series" depicts a distant interstellar civilization, mainly composed of two characters: ordinary humans and super-intelligent AI called "minds". Humans are slightly modified, and although medical technology theoretically allows humans to live indefinitely, most choose to live only about 400 years, seemingly because they become bored with life by that time.

On the surface, life as a human seems good: comfortable, health problems are addressed, there are abundant entertainment options, and there is a positive and synergistic relationship between humans and the "mind." However, a closer look reveals a problem: it seems that the "mind" is completely in control of everything, and the only role of humans in the story is to act as the pawns of the "mind" and perform tasks on their behalf.

Quoting from Gavin Leech's "Against Civilization":

Even though the book seems to have human protagonists doing big, serious things, humans are not the protagonists of the story; they are actually agents of artificial intelligence. (Zakalwe is one of the only exceptions, as he can do immoral things that Minds are unwilling to do.) "Minds in the Civilization series don't need humans, but humans crave to be needed." ” (I think only a few humans need to be needed, or a few of them needy enough to give up many comforts. Most humans don’t live on this level. Still a good criticism.)

Projects undertaken by humans carry unreal risks. Machines can do almost anything better. What can you do? You can command your mind not to catch you when you fall off a cliff; you can delete your brain backup and put yourself at real risk. You can also leave civilization and join some old-fashioned, illiberal "strongly rated" civilization. Or spread the word about freedom by joining Contact.

I think even giving humans "meaningful" roles in the Civilization series is a stretch; I asked ChatGPT (who else?) why humans are given the roles they play, rather than "minds" doing it themselves All things considered, I personally find its answer rather disappointing. In a world dominated by "friendly" super-intelligent AI, it seems difficult to allow humans to serve as anything other than pets.

Many other science fiction series depict a world where superintelligent AI exists, but these artificial intelligences obey the orders of (unaugmented) biological human masters. Star Trek is a great example of a vision of harmony between a starship and its AI "computer" (and Data) and its human operator crew. However, this balance seems to be very unstable. The world of "Star Trek" seems pleasant in the present, but it's hard to imagine that its vision of the relationship between artificial intelligence and humanity is nothing more than a world where starships are completely controlled by computers, and there is no need to bother with designing halls, artificial gravity and climate control. ten-year transitional stage.

In such a situation, a human being giving orders to a super-intelligent machine will make the human being far less intelligent than the machine and have less information. In a universe where there is competition to any degree, those civilizations in which humans play a secondary role will be superior to those in which humans stubbornly insist on control. Additionally, the computer itself may seize control. To understand why, imagine that you are legally a literal slave to an eight-year-old child. If you could have a long conversation with a child, do you think you could convince the child to sign a piece of paper that would set you free? Although I have not conducted this experiment, my intuitive answer is yes. So overall, humans becoming pets seems like a very hard-to-escape attractor, without having to worry about designing halls, artificial gravity, and climate control.

The sky is near and the emperor is everywhere

The Chinese proverb "The sky is high and the emperor is far away" expresses the basic fact about the limits of political centralization. Even in nominally large and autocratic empires—in practice, and especially in the larger autocratic empires—there are practical limits to the leadership's influence and attention, weakened by the need for the leadership to entrust local agents to enforce its will. of its ability to carry out its intentions, so there will always be a degree of practical freedom. Sometimes this can have adverse effects: the lack of distant states enforcing uniform principles and laws can create space for local overlords to steal and oppress. But if central power deteriorates, practical limits on attention and distance may put practical limits on how bad it can go.

In the age of artificial intelligence, this is no longer the case. In the 20th century, modern transportation technology made distance constraints less effective than before on central power; the large-scale totalitarian empires of the 1940s were in part a result of this. In the 21st century, scalable information collection and automation may mean that attention will no longer be a constraint. The complete disappearance of the natural limits to the existence of government could have dire consequences.

Digital authoritarianism has been on the rise for a decade, and surveillance technology has given authoritarian governments a powerful new tactic to suppress opposition: allowing protests to take place, then detecting and quietly taking action against participants after the fact. In fact, what I worry about is that the same type of management technology as OpenAI, which enables it to serve more than 100 million customers with 500 employees, will also make a political elite of 500 people, or even a 5-person board of directors, have no control over the entire company. The country maintains its rule with an iron fist. With modern surveillance technology to gather information, and modern artificial intelligence to interpret it, there may be no hiding place anymore.

Things get even worse when we consider the consequences of artificial intelligence in warfare. Translated from a semi-famous Sohu article in 2019, with modern surveillance technology to collect information and modern artificial intelligence to interpret it, there may be no place to hide anymore.

"No need for political and ideological work and wartime mobilization" mainly means that the top commander of the war only needs to consider the situation of the war itself, just like playing chess, and does not need to worry about the "knights" and "chariots" on the chessboard. What are you thinking about right now? The war became a purely technological contest.

At a deeper level, "political and ideological work and wartime mobilization" require that anyone launching a war must have a legitimate reason. The importance of having justification, a concept that has governed the legality of war in human societies for thousands of years, should not be underestimated. Anyone who wants to start a war must find at least a plausible reason or excuse. You might say this constraint is weak because, historically, it has often been little more than an excuse. For example, the real motivation behind the Crusades was plunder and territorial expansion, however, they were carried out in the name of God, even if the targets were the devout in Constantinople. However, even the weakest constraint is still a constraint! This mere excuse actually prevents the militants from completely letting their goals go unchecked. Even a man as evil as Hitler could not wage war without reservation; he had to spend years convincing the German people of the need for the aristocratic Aryan race to fight for their living space.

Today, "people in circles" serve as an important check on the power of dictators to wage war or oppress citizens at home. People in the loop prevented nuclear war, kept the Berlin Wall open, and saved lives during atrocities like the Holocaust. If armies were made up of robots, this constraint would disappear entirely. A dictator might be drunk at 10 p.m., angry at 11 p.m. because someone was unkind to them on Twitter, and then before midnight, a fleet of robot invasions might cross the border and wreak havoc on a neighboring country's civilians and infrastructure.

Unlike previous eras, there were always some far-off corners, far away, where opponents of a regime could reorganize, hide, and ultimately find ways to improve things. However, with the development of artificial intelligence in the 21st century, a totalitarian regime may maintain enough "blockade" by monitoring and controlling the world enough to never change.

d/acc: Defense (or Dispersion, or Difference) Accelerationism

Over the past few months, the "e/acc" ("effective accelerationist") movement has made great progress. "Beff Jezos" concluded that e/acc is basically a recognition of the truly huge benefits brought by technological progress, and the desire to accelerate this trend to obtain these benefits earlier.

There are many situations where I find myself sympathetic to e/acc's perspective. There is much evidence that the FDA is too conservative in delaying or blocking drug approvals, and bioethics in general seems to often follow this principle: "It is a tragedy that 20 people die in an experiment that fails, but 200,000 people die because of the delay." Treatment is just a statistic." Delays in approving COVID tests and vaccines, as well as malaria vaccines, seem to reinforce this. However, this view may be too much to be admired.

In addition to my AI-related concerns, I feel particularly ambivalent about e/acc's enthusiasm for military technology. In the current scenario of 2023, where this technology is manufactured in the United States and used to defend Ukraine, it can be seen that it can serve as a force for good. From a broader perspective, however, enthusiasm for modern military technology seems to require the belief that those who dominate technological forces in most conflicts are and will always be the good guys, and that military technology is good because military technology is Built and controlled by America, and America is good. Is e/acc about to become an American supremacist? To bet all your chips on the present and future ethics of government and the future success of the country?

Further reading: The President of Ukraine signs a bill: Fully legalizing cryptocurrencies! Negotiations to end Russia-Ukraine war involve "neutrality plan"

On the other hand, I think there needs to be new ways of thinking about how to reduce these risks. OpenAI's governance structure is a case in point: it appears to be a well-intentioned effort to balance the need to be profitable in order to satisfy the investors who provided the initial capital, while also looking to create a system of checks and balances to fend off those A move that could lead to OpenAI destroying the world. In practice, however, their recent attempt to fire Sam Altman makes this structure look like a complete failure: It concentrates power in an undemocratic, unaccountable five-person board of directors who base their decisions on secret information. make critical decisions and refuse to provide any details until threatened. Somehow nonprofit boards are performing so poorly that company employees have formed an impromptu union to support the billionaire CEO instead of them.

Further reading: Why was Sam Altman fired? A detailed explanation of the power struggle within OpenAI

Across the board, I see too many plans to save the world that involve giving extreme and opaque power to a tiny number of people and hoping they will use it wisely. So I find myself gravitating towards a different philosophy, one that has detailed ideas about how to deal with risk, but one that seeks to build and maintain a more democratic world and that tries to avoid the centralization of power as the first solution to problems . This philosophy involves much more than AI, and I will use the name d/acc to refer to this philosophy.

The "d" here can stand for many things, especially defense, decentralization, democracy, and difference. First, think of it as a defense, and then we can see how this relates to other explanations.

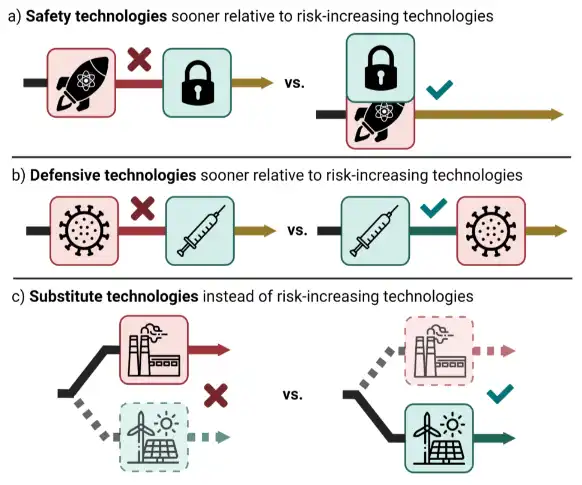

A defensive world where health and democratic governance thrive

One way to think about the consequences of a technological monolithic view is to look at the balance of defense and offense. Some technologies make it easier to attack others, broadly speaking: by doing things that go against their interests and make them feel the need to react. While other technologies make defense easier without even relying on large centralized actors.

A world that favors defense is a better world for many reasons. First, of course, are the direct benefits of security: fewer deaths, less economic value lost, less time wasted on conflicts. What is less appreciated, however, is that a more defensive world makes it easier for healthier, more open, and more freedom-respecting forms of governance to thrive.

One obvious example is Switzerland. Switzerland is often cited as the closest thing in the real world to a classical liberal governance utopia. Huge amounts of power are devolved to provinces (called "states"), major decisions are decided by referendums, and many locals don't even know who the president is. How does such a country survive under challenging political pressures? Partly due to brilliant political strategy, but partly due to its extremely defensive geography created by its mountain topography.

Another example is Zomia, which has received widespread attention in James C Scott's new book "The Art of Not Being Dominated". They have largely maintained their freedom and independence, largely thanks to their mountainous terrain, and the Eurasian steppe serves as a counterexample to a governance utopia. Sarah Paine's discussion of maritime versus continental powers makes a similar point, although she prefers to view water as a defensive barrier rather than mountains. Indeed, this combination of ease of free trade and difficulty in forced invasion, common in Switzerland as well as in island nations, seemed to be ideal conditions for human flourishing.

When I was advising on Gitcoin Grants funding rounds within the Ethereum ecosystem, I discovered a related phenomenon. In Round 4, a clown farce broke out as some of the most lucrative beneficiaries were Twitter influencers, whose contributions were viewed as positive by some and negative by others. My interpretation of this is that there is an imbalance: secondary funding allows you to indicate that you believe something is a public good, but it does not provide a way to indicate that something is a public nuisance. In extreme cases, a completely neutral secondary funding system would fund both sides of the war. So, in round 5, I proposed that Gitcoin should include negative contributions: you pay $1 to reduce the amount of funding a project receives (and implicitly redistribute it to all other projects), and as a result a lot of people were dissatisfied Feeling dissatisfied with this.

Extended reading: Gitcoin launches Web3 passport "Gitcoin Passport", which can verify identity, protect privacy, and resist witch attacks

This seems like a microscopic manifestation of a larger pattern to me: establishing decentralized governance mechanisms to deal with negative externalities is a very difficult problem in society. The classic example of decentralized governance gone wrong is often crowd justice. There's something about human psychology that makes dealing with negative things much trickier, and more likely to cause serious problems, than dealing with positive things. This is why, even in otherwise highly democratic organizations, the power to decide how to respond to negative issues is often left to a central committee.

In many cases, this dilemma is one of the underlying reasons why the concept of "freedom" is so valuable. If someone says something that offends you, or leads a lifestyle that you find offensive, the pain and disgust you feel are real, and you may even feel that being physically assaulted is not as bad as being exposed to these things. But trying to agree on socially acceptable offensive and obnoxious behavior may come with more costs and dangers than reminding ourselves that certain weirdos and assholes are the price we pay for living in a free society.

However, other times, a "suck it up" approach is impractical. In this case, another answer sometimes worth considering is defensive technology. The more secure the Internet is, the less we need to invade people's privacy and use unfair international diplomacy to deal with individual hackers. The more we can build personalized tools for blocking people on Twitter, in-browser tools for detecting fraud, and collective tools for distinguishing rumor from truth, the less we have to argue about censorship. The faster we produce vaccines, the less we have to deal with super-spreaders. These solutions won't work in all areas, and we certainly don't want to see a world where everyone has to wear real body armor, but in areas where we can leverage technology to make the world more defensive, there's huge value in doing so.

This core idea, that some technologies are good for defense and worth promoting, while other technologies are good for offense and should be suppressed, has its roots in the effective altruism literature that appears under a different name: differential technology development. In 2022, researchers at the University of Oxford put this principle well:

There will inevitably be imperfections when classifying techniques as offensive, defensive or neutral. Like "liberty," one can debate whether social democratic government policies reduce freedom by imposing heavy taxes and forcing employers, or whether they increase freedom by reducing ordinary people's concerns about many kinds of risks. Like "liberty," "defense" There are also technologies that may be at both ends of the spectrum. Nuclear weapons are good for offense, but nuclear power is good for human prosperity and is neutral between offense and defense. Different technologies may work differently over different time frames. But like “liberty” (or “equality” or “the rule of law”), the blurring around the edges is not an argument against a principle but an opportunity to better understand its subtleties.

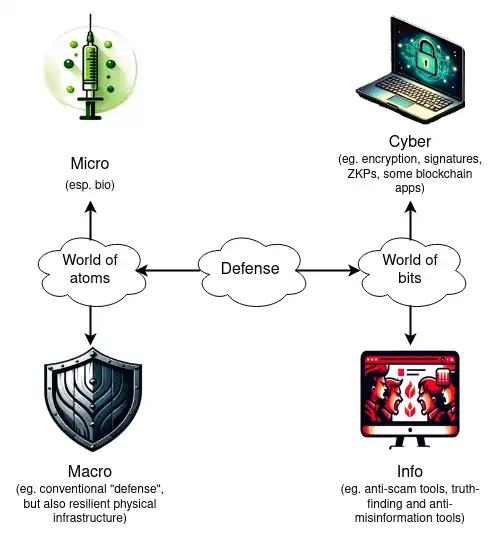

Now, let’s see how this principle can be applied to a more comprehensive view of the world. We can think of defense technology like other technologies, divided into two realms: the atomic world and the bit world. The atomic world can be divided into the microscopic (i.e., biology, and later nanotechnology) and the macroscopic (i.e., what we traditionally think of as “defense,” but also includes resilient physical infrastructure). I split the bit world on different axes: in principle it is easy to agree, who is the attacker? Sometimes it's easy; I call it cyber defense. Other times, it's more difficult; I call it information defense.

Macroview physical defense

The most underrated defense technology in the macrosphere isn’t even Iron Dome (including Ukraine’s new system) and other counter-tech and anti-missile military hardware, but rather resilient physical infrastructure. Most deaths in a nuclear war would likely come from supply chain disruptions rather than initial fallout and shock, and low-infrastructure internet solutions like Starlink have been critical to keeping Ukraine connected over the past year and a half. important.

Building tools to help people survive independently or semi-independently or even live comfortably in long-term international supply chains appears to be a valuable defensive technology and less risky for use offensively.

The task of trying to make humanity a multi-planetary civilization can also be viewed from a d/acc perspective: having at least some people able to live self-sufficiently on other planets could increase our resilience to horrific events on Earth. Even if the full vision currently seems unfeasible, the forms of self-sufficient life that would need to be developed to realize this project may well be used to help increase the resilience of our civilization on Earth.

Microphysical defense (also known as biological defense)

Covid remains a concern, particularly due to its long-term health effects. But Covid is far from the last pandemic we will face; many aspects of the modern world make it likely that more pandemics are coming:

- Higher population density makes it easier for airborne viruses and other pathogens to spread. Epidemic diseases are relatively new in human history, with most beginning with urbanization thousands of years ago. Ongoing rapid urbanization means that population density will increase further over the next half century.

- Increased air travel means airborne pathogens can spread rapidly around the world. People are rapidly getting richer meaning air travel is likely to increase significantly over the next half century; sophisticated modeling shows that even small increases could have serious consequences. Climate change may further increase this risk.

- Animal domestication and factory farming are major risk factors. Measles may have evolved from a bovine virus less than 3,000 years ago. Today’s factory farming is also creating new strains of influenza viruses (as well as promoting antibiotic resistance, with implications for the human innate immune system).

- Modern bioengineering makes it easier to create new, more virulent pathogens. Covid may or may not have leaked from a lab conducting intentional "enhancement" research. Regardless, lab leaks happen, and tools are rapidly improving, making it easier to intentionally create extremely deadly viruses, and even prions (zombie proteins). Artificial plagues are particularly worrisome, in part because, unlike nuclear weapons, they are not attributable: You can release a virus and no one can tell who created it. It is now possible to design a genetic sequence, send it to a wet lab for synthesis, and have it shipped to you within five days.

This is one of the areas where two organizations, CryptoRelief and Balvi, were founded and funded in 2021 by a large windfall of Shiba Inu coins. Initially focused on responding to the immediate crisis, CryptoRelief has more recently been building a long-term medical research ecosystem in India, while Balvi has been focused on forward-thinking projects that improve our ability to detect, prevent and treat Covid and other airborne diseases. ++Balvi insists that projects funded by it must adopt an open source approach++. Drawing inspiration from the 19th-century hydraulic engineering movement that defeated cholera and other waterborne pathogens, it funds projects across a whole spectrum of technologies that could make the world more resilient to airborne pathogens by default, including :

・Far-UVC radiation research and development

・Air filtration and quality monitoring, as well as air quality monitoring in India, Sri Lanka, the United States and other places

・Cheap and effective decentralized air quality testing device

・Study of long-term Covid causes and potential treatment options (the main cause may be simple, but clarifying the mechanism and finding a treatment option is more difficult)

・Vaccine (e.g. RaDVaC, PopVax) and vaccine injury research

・A new set of non-invasive medical tools

・Use open source data analysis for early detection of epidemics (e.g. EPIWATCH)

・Testing, including very cheap molecular rapid tests

・Biosafety masks for use when other methods fail

Other promising areas of research include wastewater monitoring for pathogens, improving filtration and ventilation in buildings, and better understanding and mitigating risks caused by air pollution.

There is an opportunity to build a world that is more resilient to natural and artificial airborne epidemics by default. This world will have a highly optimized process where we can detect an epidemic automatically, starting from the beginning, and people around the world can have access to targeted, locally manufactured and verifiable open-source vaccines or other preventive measures within a month, through fog Chemical or nasal spray administration (i.e. self-administration when needed, no injection required). At the same time, better air quality will drastically reduce transmission rates and prevent many epidemics from being stifled in their infancy.

Imagine a future without having to resort to the hammer of social coercion – without mandates and worse, without risky, poorly designed and implemented mandates that could make matters worse – because public Health infrastructure is woven into the fabric of civilization. Such a world is possible, and with modest investments in biodefense, it can be achieved. Work would be smoother if these developments were open source, freely available to users, and protected as public goods.

Cyber defense, blockchain and cryptography

Security professionals generally agree that the current state of computer security is terrible. Still, it’s easy to underestimate the progress that has been made. Tens of billions of dollars in cryptocurrencies can be stolen anonymously by anyone who can hack into a user's wallet, and while the percentage stolen or stolen is far greater than I'd like, the reality is that most of the cryptocurrencies haven't been for over a decade. Stolen. There have been some recent improvements:

- The device has a trusted hardware chip built into it , effectively creating a smaller, highly secure operating system within the user's phone that can remain secure even if the rest of the phone is hacked. These chips are increasingly being explored as a way to build more secure crypto wallets, and are part of a number of use cases.

- The browser serves as the de facto operating system . Over the past decade, there has been a quiet shift from downloadable apps to browser-based apps. This is largely due to WebAssembly (WASM). Even Adobe Photoshop, long considered one of the main reasons many people couldn't actually use Linux due to its necessity and incompatibility with Linux, is now Linux-friendly by being embedded in the browser. This is also a big security advantage: while browsers do have their flaws, in general they offer more sandboxing than installed apps: apps can't access arbitrary files on your computer.

- Strengthen the operating system . GrapheneOS for mobile exists and is very usable. A desktop version of QubesOS also exists; in my experience it's currently slightly less usable than Graphene, but it's improving.

- Try to look beyond passwords . Passwords are difficult to protect because they are difficult to remember and can be easily eavesdropped. Lately, there's been a growing movement to reduce reliance on passwords and make hardware-based multi-factor authentication actually work.

Extended reading: Slow Mist Technology: "Self-Help Manual" in the Dark Forest of Blockchain

However, a lack of cyber defense in other areas has also led to significant setbacks. The need to protect against spam has caused email to become very oligarchical in practice, making it difficult to self-host or set up a new email provider. Many online applications, including Twitter, require users to log in to access content and block IP addresses using VPNs, making it more difficult to access the Internet in a privacy-preserving manner. Centralization of software also carries risks because of "weaponized interdependence": modern technologies tend to flow through centralized bottlenecks whose operators use this power to collect information, manipulate outcomes or exclude specific actors. This tactic even appears to be being used against the blockchain industry itself.

These trends are worrisome because they threaten historically one of my major hopes for future prospects for freedom and privacy. In David Friedman's book "Future Imperfections," he predicts that we may be facing a compromise future: the real world will be increasingly monitored, but through cryptography, the online world will be preserved and even improved. its privacy. Unfortunately, as we have seen, such a countertrend is far from certain.

This is my emphasis on cryptographic technologies such as blockchain and zero-knowledge proofs. Blockchain allows us to build economic and social structures with "shared hard drives" without relying on centralized actors. Cryptocurrencies enable individuals to store and conduct financial transactions much like cash was used before the Internet, without having to rely on trusted third parties who can change the rules at will. They can also serve as backup anti-Sybil mechanisms, making attacks and spam expensive for users who do not or do not want to reveal their entity's identity. Account abstraction, especially social recovery wallets, can protect our crypto assets, and potentially other assets in the future, without over-reliance on centralized intermediaries.

Extended reading: Popular science | What is ZK zero-knowledge proof? Vitalik believes that blockchain will be as important as blockchain in ten years’ time

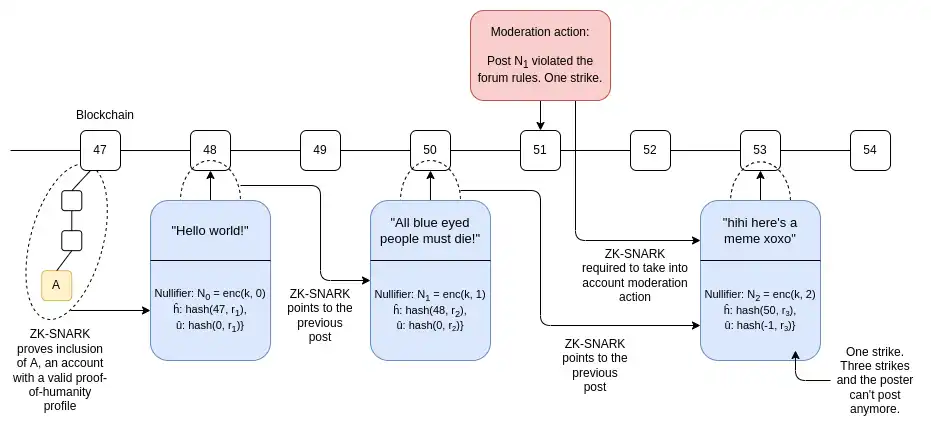

Zero-knowledge proofs can be used for privacy, allowing users to prove facts about themselves without revealing private information. For example, wrapping a digital passport signature in a ZK-SNARK proves that you are the only citizen of a certain country without revealing which citizen you are. Similar technologies allow us to maintain the benefits of privacy and anonymity – features widely considered necessary for applications such as voting – while still gaining security guarantees and fighting against spam and bad actors.

Zupass is an excellent example of a practice incubated at Zuzalu. This is an app, already used by hundreds of people at Zuzalu and more recently by thousands of people at Devconnect for ticketing, that allows you to hold tickets, memberships, (non-transferable) digital collectibles and other certificates, and certify all matters relating to them without divulging privacy. For example, you can prove that you are the only registered resident of Zuzalu, or a ticket holder for Devconnect, without revealing other information about who you are. These proofs can be displayed in person or digitally via QR codes to log into apps such as Zupoll, an anonymous voting system only available to Zuzalu residents.

Extended reading: Revealing the secret of Vitalik’s social experiment Zuzalu: an elite utopia located on a beautiful beach

These technologies are excellent examples of the d/acc principle: they allow users and communities to verify trustworthiness without compromising privacy, and protect their security without relying on centralized choke points that imposes its own definition of who the good guys and bad guys are. They improve global accessibility by establishing better and more just ways to protect the security of users or services than is common today by discriminating against entire countries deemed untrustworthy. These are very powerful primitives that may be necessary if we hope to preserve a decentralized vision of information security as we enter the 21st century. A broader commitment to defensive technologies in cyberspace can play a very important role in making the Internet more open, secure, and free in the future.

Information defense

Info-defense is what I describe as cyber defense, dealing with situations where there is easy consensus among reasonable humans on the identity of the attacker. If someone tries to hack into your wallet, it’s easy to assume that the hacker is the bad guy. If someone attempts to conduct a DoS attack on a website, it is easy for everyone to assume that they are malicious and morally different from ordinary users trying to read the content of the website. There are other cases where the lines are even more blurred. I call the tools for improving our defenses in these situations "information defenses."

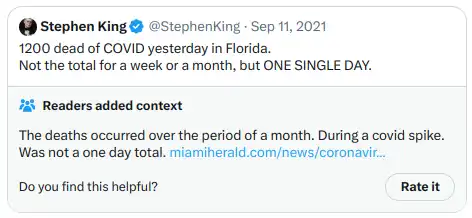

Take fact-checking (also known as preventing "misinformation"), for example. I really like Community Notes, it does a lot to help users identify truth and lies in other users' tweets. Community Notes uses a new algorithm that displays not the most popular notes, but the notes with the most approval from users across the political spectrum.

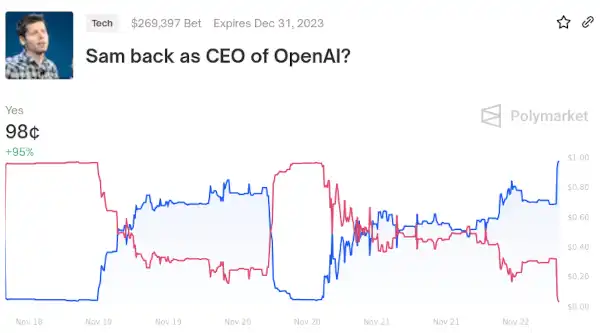

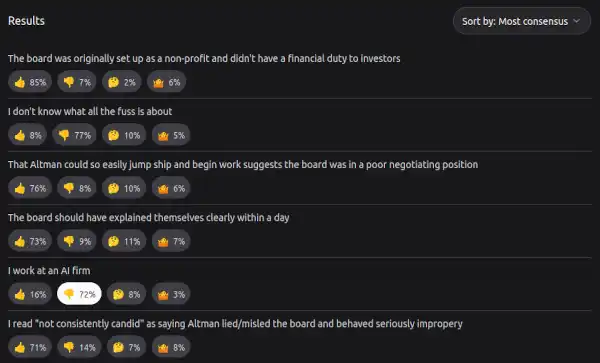

I’m also a fan of prediction markets, which can instantly reveal the significance of an event before it becomes clear and before there’s a consensus on where things are going. For example, the Polymarket on Sam Altman provides a very useful summary of the hour-by-hour revelations and negotiations, providing much needed context for those who only see individual news items without understanding the significance of each one.

Extended reading: Taiwan’s presidential election becomes an on-chain betting market! Lai Qingde’s odds are nearly 1.5 and he has earned more than 4 million

Prediction markets are often flawed, but Twitter influencers who are willing to confidently state what they think will happen in the next year are often even more flawed. Prediction markets still have a lot of room for improvement. For example, prediction markets generally have low trading volumes on all but the most high-profile events; a natural direction to address this problem is to launch prediction markets involving artificial intelligence.

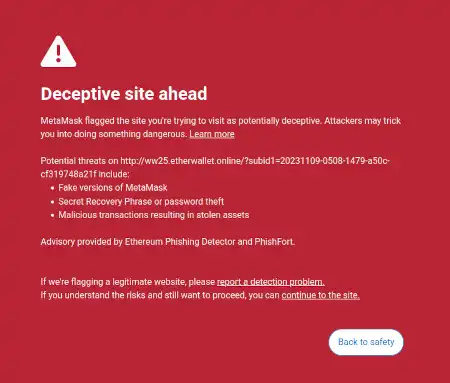

In the blockchain space, I think we need more of a specific type of information defense. That said, wallets should be more insightful and proactive in helping users determine the meaning of the things they sign, and protect them from fraud and scams. This is a middle-ground case: what is and is not a scam is less subjective than opinions on controversial social events, but more subjective than distinguishing legitimate users from DoS attackers or hackers. Metamask already has a fraud database and automatically blocks users from accessing fraudulent websites.

Apps like Fire are an example of a deeper approach. However, security software shouldn’t be something that needs to be explicitly installed; it should be a default setting for crypto wallets or even browsers.

Because information defense is more subjective, it is more collective in nature than cyber defense: you need to somehow be connected to a large and complex group of people to determine what information may be true or false, and what kind The app is a fraudulent Ponzi scheme. Developers have the opportunity to make greater progress in developing effective information defenses and to enhance existing forms of information defenses. Things like Community Notes can be included in the browser, covering not just social media platforms but the entire Internet.

Social technology beyond the “defense” framework

To some extent, I might be accused of being too emphatic in characterizing some information technologies as "defensive." After all, defense is about helping to protect well-intentioned actors from malicious actors (or, in some cases, from nature). However, some of these social technologies help well-intentioned actors develop consensus.

A good example of this is pol.is, which uses an algorithm similar to Community Notes (and predates Community Notes) to help communities identify points of consensus among different subgroups that are in many ways There are disagreements. Viewpoints.xyz is inspired by pol.is and has a similar spirit:

Techniques like this can be used to enable more decentralized governance over contentious decisions. Again, the blockchain community is a venue for good practice in this area and has demonstrated the value of these algorithms. Generally, decisions about what improvements ("EIPs") to make to the Ethereum protocol are made by a fairly small group in meetings called "All Core Devs calls." This works well for decisions that are highly technical and that most community members don't feel strongly about. For more important decisions involving protocol economics, or more fundamental values like immutability and censorship resistance, this is often not enough. Looking back at 2016-17, when implementing a series of controversial decisions such as the DAO ha